Triumph, terror and tragedy: The incredible story of Clipper Victor, the first 747

The “life” of an aircraft is generally quite a mundane thing. It spends 30 or so years in the sky, flying through the same grooves of airspace, with nothing more worrying than the occasional bout of turbulence or heavy weather to ruffle its mechanical feathers. True, it touches down on runways in exotic places and far-flung locations – assuming it is flying long-haul routes. But its three-decade existence is usually a repetitive slog, peppered with an overhaul or two. The afterlife may bring a last photo-opportunity, if the retiree makes it to the fabled aviation “boneyard” in the Mojave Desert. In most cases, though, the final act is a dismantling for reusable parts, and an unsentimental scrapping of everything else.

Of course, there are exceptions to this rule. And none more exceptional, perhaps, than the Boeing 747-121 which went under the registration N736PA – but was better known as “Clipper Victor”. No other aircraft has a comparable story. It flew for just a little over seven years, between January 22 1970 and March 27 1977 – with the entirety of its service taking place in the colours of Pan Am. But in those seven years, it experienced more than most airliners manage in “careers” four times as lengthy. Much, much more.

If you will, its story can be split into three chapters.

Triumph

In the very first days of 1970, the Boeing 747 was the shiny new kid emerging from a revolutionary engineering block. The Seattle-based aircraft manufacturer had been working on its most remarkable project yet for the best part of a decade – agreeing to Pan Am’s request that it design an airliner bigger than anything that had come before; a game-changer that could carry more passengers for longer distances – easing the growing congestion in the skies and bringing down the cost of air travel in the process. The 747 was a mould-breaker, crafted with an upper deck to accommodate “premium” passengers, and able to transport up to 480 travellers in total. It was so big that Boeing had to build a new plant in which to construct it – choosing a site 30 miles north of Seattle, near Everett.

Clipper Victor would be the star of this future-shaping show. But only inadvertently. And with a certain element of farce. When Pan Am committed to putting the first commercial flight of a Boeing 747 into the air, it handed the honour to a different 747-121. Clipper Young America had been the first of these fresh-hewn giants to trundle off the Boeing conveyor belt and into Pan Am employment, and it was this plane that was set to operate the aircraft’s inaugural journey with paying customers in its seats – a non-stop service from New York’s John F. Kennedy Airport over to London Heathrow on January 21 1970.

Unfortunately for Clipper Young America, it endured an attack of big-night nerves. First it suffered a door malfunction. A late-arriving passenger, bursting aboard, interrupted the automatic closing cycle of the main port-side door in the forward economy cabin. The resultant jamming of the mechanism took half an hour to fix – and by the time the aircraft began to taxi, its engine was starting to overheat. A sudden gust of wind, directly into the exhaust vent of the right outboard engine, would compound the problem by causing the fuel to flare up. “It’s marvellous,” one passenger, Joyce Susskind would be quoted as saying in Time magazine’s coverage of the event. “A dozen bathrooms, and no engines.”

Clipper Young America would be hauled unceremoniously back to the gate, and Clipper Victor sent out in its place, a few hours later, on January 22. Time would describe the situation as “an alternately frustrating and funny experience for the 352 passengers” – the most humorous incident, perhaps, being the hasty re-decoration which occurred before take-off. “Clipper Young America” was scheduled to provide this first-of-a-kind service, and “Clipper Young America” it was that finally thundered down the runway. But only after Clipper Victor had had its nose-cone – and its own identity – whitewashed and the name of its underperforming predecessor painted in its place. The rest, at least, was plain-flying – Victor/Young America touched down in the UK six hours and 14 minutes later.

Its arrival was covered by the Associated Press (AP), which reported that the aircraft drew up at stand I-29 at 8.10am, on time of itself, but almost seven hours late thanks to the first plane’s troubles in the Big Apple. Images show blue-uniformed Pan Am flight crew waving to the assembled crowd – on a typically overcast London winter morning.

The reactions of those who disembarked with them were mixed. One passenger declared his annoyance. “The plane is simply too big for anyone to be given proper service,” he grumbled. Others were delighted. “The flight was simply great,” said (Mrs) Joe Tepera of Fort Worth, Texas. “Flying in a beautiful plane like that was worth the delay. All the passengers were good-humoured, and when the plane finally took off, they applauded. They did the same when it landed. I personally wouldn’t hesitate to fly in a jumbo again.”

Its sacred task completed, the plane would shed its briefly-adopted pseudonym, and revert to “Clipper Victor”. But the original Clipper Young America would not regain its name. It was rechristened Clipper Constitution, and would have a series of rebrandings – Clipper Washington, Clipper Pride of the Sea, Clipper Air Express – until, 18 years after fluffing its lines, it had its moment of glory. On May 15 1988, as “Clipper Moscow Express”, it flew the first non-stop Pan Am service from New York to the Russian capital.

Terror

Clipper Victor had barely wiped the London drizzle from its wings before it was breaking new ground – or, at least, airspace – for a second time. Only this time, the record was unwanted. Just half a year later, on August 2 1970, it became the first 747 to be hijacked.

It should have been a simple day; a flight out of New York, three-and-a-half hours down into the Caribbean, to San Juan, on an island – Puerto Rico – that is also a US Territory. But instead, at 2.47am, one hour and 40 minutes after the plane had departed from JFK, a bearded young man stood up in the first class section, and demanded to be taken to Cuba.

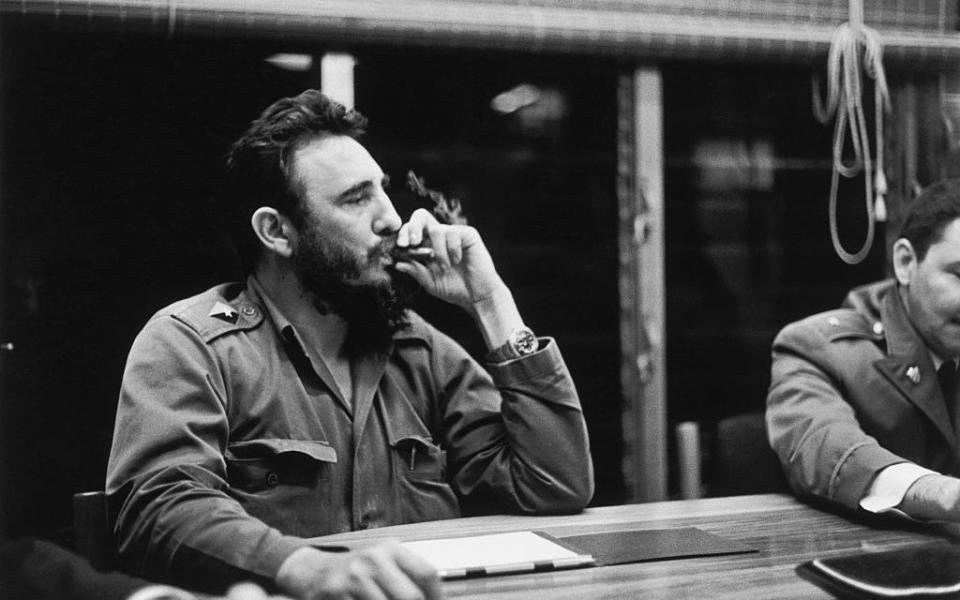

It is easy to imagine the fear this might have struck into the 379 – largely American – crew members and passengers aboard Clipper Victor that night. It may have been over 11 years since the Caribbean’s biggest island country had fallen fully to Fidel Castro’s communist forces (in January 1959), but the Cold War was alive, and the announcement that the 747 was being diverted to Havana would have terrified many. Or, at least, it should have done. Perhaps it was because the hijacking occurred in a more confident age; an era prior to 9/11, when a certain innocence had not been lost. Or perhaps it was because hijackings were a relatively common problem in the Seventies – a potent way of “making a point” favoured by terror groups and radical organisations. But contemporary reports of what happened during that summer morning seemed to treat it almost as one big misadventure.

Indeed, the account in the New York Times resembled the first draft of a script for an oddball comedy film, or a fantastical sketch on a satirical television series. In particular, the recollections of Pan Am stewardess Esther de la Fuente make for remarkable reading.

It was Ms de la Fuente who was closest to the scene when the hijack began.

“He pulled out a gun, pointed it at me, and said, ‘Take me to the captain, because I want to go to Cuba’,” the New York Times recorded her saying. “I thought he was joking,” she continued. “I replied: “No, let’s go to Rio – it’s a lot more fun there at this time of year.

“Then he pulled out a bottle, which he said contained explosives, and warned me that he was not kidding,” she added. “I took him to the captain.”

Some of the passengers appear to have been only a little more ruffled than the cabin crew. Rosa Troche, a Dominican woman, was even sitting next to the terrorist when he made his move. “I never knew what was going on until I saw him point a gun at the stewardess,” she would later remember. “Then I knew we were on our way to Havana.”

Rudely interrupted in the cockpit, Captain Augustus Watkins acceded to the hijacker’s instructions, tilted Clipper Victor a little to the south-west, and proceeded to Jose Marti International Airport, on the outskirts of Havana – where matters took an even more implausible turn. When it touched down at 5.31am, it was greeted by none other than Cuba’s notorious leader. And what did the bogeyman of American political imaginations want? Bloodshed? Hostages? To make a loud statement on the international stage? No, he wanted what everyone else wanted in that summer of 1970 – a close look at a Boeing 747.

“The only people to get off the plane were me and the hijacker,” Watkins explained. “I met Fidel, and took him for a tour of the outside of the plane. He asked all manner of questions related to its capacity and speed. He was particularly interested in whether the plane would be able to take off from the Cuban airfield. I told him it wasn’t a problem.”

The two men were speaking through an interpreter, but the surreal nature of the situation was not lost in translation. Watkins asked his unexpected “host” if he would like a tour of the inside of the plane. Castro declined. “I would probably scare the passengers,” he said.

Clipper Victor was only on the tarmac in Havana for 52 minutes. It might have been an even shorter window, but for one further farcical note. “The hijacker wanted to get his luggage off the plane before we took off,” Watkins said. “And I had to explain to him and Castro that this couldn’t be done on the 747 without special baggage-handling equipment, which was not available in Havana. After I promised to see that the luggage was shipped to Havana on another flight, Castro gave the orders to clear us for take off [at 6.23am].”

And that was that. Clipper Victor departed without a hijacker who was only ever identified by the presumably fake name – “R Campos” – with which he had boarded in New York, but with his bags. Watkins described him as a man “with a black beret and a short beard, who looked like a pint-sized Che Guevara”. Esther de la Fuente thought he was Chilean or Peruvian, but said he spoke of Havana and its airport with a familiarity which suggested he had been there before. Whoever he was, he was not on board when the 747 touched down to refuel in Miami at 7.10am, and nor when it arrived in San Juan at 10.45am – six hours and 40 minutes later than planned – to be swamped by FBI agents.

Tragedy

Clipper Victor’s subsequent six years were rather more uneventful. But when it reached the last chapter of its short but incredible life on March 27 1977, the story faded to black.

Much has been written about the Tenerife Airport Disaster – a dreadful day in the east Atlantic. But its horror is undimmed by time’s passing. Contrary to its image as a hotspot of year-round warmth and easy suntans, the largest of the Canary Islands was shrouded in fog that Sunday afternoon. By the time visibility cleared, two Boeing 747s had collided, and 583 people had been killed, in what remains the deadliest aviation accident in history.

Clipper Victor should not have been there. Nor should its fellow victim of the accident, a KLM Boeing 747-206B, with the name Rijn (Rhine). But at 1.15pm that lunchtime, a bomb planted by separatist group the Canary Islands Independence Movement had exploded in the terminal at Las Palmas Airport, on neighbouring Gran Canaria. Both 747s had been bound for this larger air facility, which is better able to handle planes of such size – the Pan Am plane had come in from Los Angeles via JFK; its KLM counterpart had flown from Amsterdam, stuffed full of Dutch holidaymakers. Requests to fly in a holding pattern rather than switch airports were denied. The Pan Am crew made repeat assertions that the aircraft had enough fuel to circle for two hours while waiting for Las Palmas to reopen, but were told to land at Tenerife’s Los Rodeos Airport, 60 miles to the north-west.

Los Rodeos is still there today, rebranded as Tenerife North, having been partially superseded by the opening of the bigger, more modern Tenerife South in 1978. It has been upgraded in the four decades since, and still receives international flights, as well as local services. But it has an unusual set-up for an island airport. Rather than being built on reclaimed land at sea level, it sits high on the landmass. Really high. Its altitude – 633m (2,077ft) – means it is prone to misty conditions and sharp changes in weather. And in March 1977, this was exactly the situation that faced the planes being diverted in from Las Palmas. Los Rodeos was not the ideal airport for a Boeing 747, let alone two of them.

What happened was a catastrophe which unfolded in slow motion, then at awful speed. In total, five larger airliners had been redirected from Gran Canaria – so that, come mid-afternoon, Los Rodeos resembled less an airport, more a car park. The main taxi-way was blocked with waiting planes, meaning that pilots preparing for take-off needed to steer their aircraft into position along the runway – rather than alongside it. Trouble beckoned.

Las Palmas Airport was soon reopened. But a log-jam remained on Tenerife, where a fraught situation was exacerbated by further complications. The KLM plane had misplaced four of its passengers – a family of four who had disembarked, but not returned to the plane. They had to be found. The Dutch 747 was also held up by its captain opting for an unscheduled refuelling that could have been done on La Palma – believing that this would save time. This delayed its departure by 35 minutes, and equally inconvenienced Clipper Victor, which, amid the congestion, did not have space to move around it safely.

The crew of the KLM cockpit were men of considerable expertise, reporting to 50-year-old Captain Jacob Veldhuyzen van Zanten – the airline’s chief flight instructor. Their Pan Am counterparts – led by 56-year-old Captain Victor Grubbs – were no less experienced.

Eventually, the KLM aircraft was instructed to taxi down the runway, and into position for take-off. Clipper Victor was requested to follow, but take one of the four short connecting taxi-ways off to the side, and await its turn. Yet conditions were still bleak, the taxi-ways were unmarked, and in the confusion and the murk, disaster struck. The Pan Am plane was still partially on the runway when the KLM cockpit misunderstood a message from the control tower as clearance to depart. A desperately ill-timed burst of radio interference blocked out the urgent response from the Pan Am cockpit: “We’re still taxiing down the runway, the Clipper 1736!”. The final statement from Veldhuyzen van Zanten as the engines roared and his 747 began to advance was “We gaan.” We’re going.

Flight recorder transcripts show that the Pan Am cockpit first saw the KLM plane emerging from the gloom when it was 700 metres away. Grubbs was the first to speak: “There he is… look at him. Goddamn, that son of a b***h is coming”. The reaction of First Officer Robert Bragg was more urgent – “Get off! Get off! Get off!”. Veldhuyzen van Zanten’s last words, when he realised what had happened, were, simply: “Oh s**t!”.

The collision could not be avoided. Frantically, Veldhuyzen van Zanten tried to jerk his plane into the air, in an attempt to clear the obstacle – but the KLM 747 was only 100 metres from Clipper Victor when it left the runway, moving at just 160mph. Its nose cleared the Pan Am 747 – but its left-side engines, landing gear and lower fuselage did not. They ripped through the centre of the American plane, directly above the wings, while Rijn’s right-side engines tore into the Pan Am jet’s upper deck, behind the cockpit.

Perhaps, for a moment, everything seemed to freeze, as the KLM aircraft continued its ascent. But it had lost its outer left engine in the impact, the inner left had become clogged with fuselage debris, and its wings were damaged. It stalled, rolled, then hit the ground some 150 metres beyond the Pan Am 747 – before sliding for a further 300. The full load of fuel, taken on minutes earlier as a time-saving convenience, created a fireball that would burn for several hours. There were 248 people on the plane – and no survivors.

Clipper Victor was in barely better shape. The crash would take 335 of the 396 souls on board. Sixty-one incredulous survivors would stumble from the wreckage – though even here, they had, at first, to fend for themselves. As the inferno raged around the wreckage of the KLM plane, but the fog held, firefighters did not initially realise that two 747s had been involved in the crash. Clipper Victor’s last contribution to aviation history was the holes in its flanks, through which people crawled onto the wing, and dropped to the floor.

Later accounts would hail the efforts of Dorothy Kelly, a Pan Am senior flight attendant, who helped others to safety. “I was in the front of the airplane standing by a door, and not in a position where I could see out,” she would recall. “All of a sudden things were flying around the airplane. I thought a bomb may have exploded. Everything just changed in a moment. The KLM plane had peeled off the top of the Pan Am plane, like peeling off the top of a sardine can. Everyone in the top section had gone. There was nothing around that looked like anything had looked before – just jagged metal, and small pieces of debris.”

Although she broke her elbow and fractured her skull in the process, Kelly concentrated on getting the survivors outside – assisted by Bragg, who had broken his ankle. Grubbs too survived. She would deny any suggestions of heroism. “I did what I could,” she said.