Are face masks a barrier to the coronavirus?

Scientists have investigated whether face masks may be an effective barrier against the coronavirus outbreak.

The pros and cons of the personal protective equipment have been hotly debated.

While they may seem harmless, research suggests masks are only effective when combined with other measures, like washing hands and disinfecting surfaces.

Masks also rarely cover the eyes, an entry point into the body for the coronavirus.

Early research suggests the infection is mild in four out of five cases, however, it can trigger a respiratory disease called COVID-19.

To learn more, scientists from the University of East Anglia looked at 31 studies on the efficacy of masks at warding off infections, largely flu.

Results were mixed but fairly discouraging, ranging from a 6% risk reduction to a maximum of 19%.

The scientists and other experts concluded there is limited evidence masks protect the public from the coronavirus, however, they could keep high-risk healthcare staff infection-free.

The timely research comes as a panel that advises the World Health Organization (WHO) is said to be meeting this week to discuss the evidence for masks.

The WHO currently states “if you are healthy, you only need to wear a mask if you are taking care of a person with suspected [coronavirus] infection”.

It also advises those who are coughing or sneezing to wear a mask, a recommendation echoed by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Latest coronavirus news, updates and advice

Live: Follow all the latest updates from the UK and around the world

Fact-checker: The number of COVID-19 cases in your local area

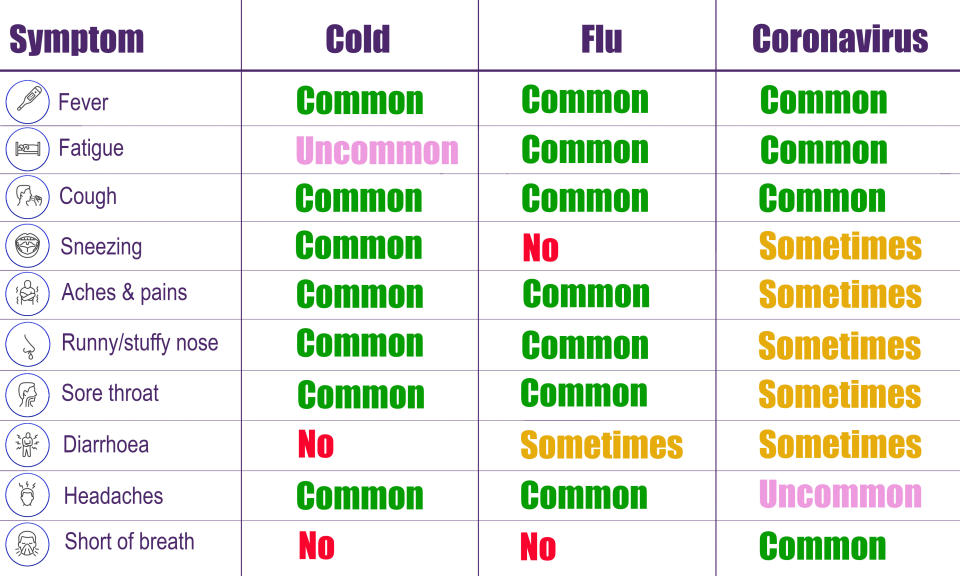

Explained: Symptoms, latest advice and how it compares to the flu

The coronavirus is thought to have emerged at a seafood and live animal market in the Chinese city Wuhan, capital of Hubei province, at the end of last year.

It has since spread into more than 180 countries across every inhabited continent.

Since the outbreak was identified, more than 1.2 million cases have been confirmed, of whom over 270,300 have “recovered”, according to Johns Hopkins University.

Incidences have been plateauing in China since the end of February, and the US and Europe are now the worst-hit areas.

The UK has had more than 48,400 confirmed cases and over 4,900 deaths.

Coronavirus: ‘Evidence not sufficiently strong to support widespread mask use’

The East Anglia research looked at three studies where the risk of developing “respiratory symptoms” was “very slightly” reduced by wearing a mask.

Other studies in the analysis suggested that when an infected individual and their housemates all wore masks, the risk of the virus passing from the patient was “modestly reduced” by around 19%.

The protective effect was “very small” if only the patient or non-infected individual wore a mask.

When worn by both infected and non-infected members of a household, the protection became “modest”.

The scientists noted much of this was based on “low-certainty evidence”.

They concluded masks may be “very slightly protective” when worn in a “community” setting, but the evidence “is not sufficiently strong to support widespread use of face masks as a protective measure against COVID-19.

“However, there is enough evidence to support the use of face masks for short periods of time by particularly vulnerable individuals when in transient higher-risk situations”, the scientists wrote in Medrxiv.

High-risk workers include frontline NHS staff treating those with coronavirus complications.

Health workers are unable to work from home as requested by the UK government, raising the risk they will encounter the infection.

Treating multiple coronavirus-positive patients also increases the viral “dose” a worker is exposed to.

Coronavirus: ‘Masks should be prioritised for healthcare workers’

The research has been published preliminarily online and is yet to appear in a peer-reviewed journal.

Peer-reviewing involves experts who were not involved in the study weighing in on its strength and weaknesses.

Nevertheless, other experts agreed the research drives home how masks should be saved for healthcare workers.

“It is important to stress this study concludes: ‘We do not consider that the balance of evidence across all available studies supports routine and widespread use of face masks in the community’, said Dr Jennifer Cole from the University of London.

“This study therefore supports the importance of prioritising limited stocks for healthcare staff and other key workers in the high-risk settings.

“It is important to synthesize what we know right now, and even though these studies largely do not relate to the current outbreak, it is the best knowledge available at present”.

Dr Simon Clarke from the University of Reading agreed, adding there is only “very limited evidence” masks protect the general public, “no evidence that wearing them in crowded places helps at all” and “no evidence at all yet related to [the coronavirus]”.

“The authors also acknowledge that mass face mask-wearing by the public would likely cause shortages among people who genuinely need protective equipment, healthcare workers on the frontline in our hospitals,” he said.

Professor Mike Barer from the University of Leicester noted how the maximum effect seen was a 19% risk reduction.

“I.e. of give exposed individuals who get infected, it was estimated only four would have been infected if masks had been used”, he said.

Professor Barer added, however, the effectiveness of masks in healthcare staff specifically was not investigated.

Dr Ben Killingley from The Whittington Hospital in London has previously stressed masks are not an “infinite resource”.

“It would not be good if we were not able to provide masks to healthcare workers because the public had consumed supplies,” he said.

Coronavirus: Why may masks not be effective for the public?

The general consensus is if an individual is infected, wearing a mask will help prevent them passing it on.

When someone without the infection wears a mask, however, they are thought to be no more protected.

The day-to-day wearing of masks is more “socially acceptable” in China, however, one expert noted this did not stop Wuhan becoming the original epicentre of COVID-19.

“On my one opportunity to visit China about 10 years ago, I was struck by the numbers of people wearing masks in the absence of any ongoing public health scares and yet enforcing this practice did little to stem the tide of the outbreak in Wuhan prior to full lockdown,” said Dr Stephen Griffin from the University of Leeds.

Studies suggest masks are effective at protecting healthcare staff, however, these are often worn in combination with other protective gear, like goggles and gloves.

These masks are also theoretically thrown away after every use. Evidence suggests masks become less effective when wet, with us all having moisture in our breath.

Hospitals are also disinfected regularly.

N95 respirator masks are thought to be among the most effective at filtering out microscopic pathogens.

Many people find them uncomfortable, however, and complain of breathing difficulties.

Professor Jonathan Ball from the University of Nottingham previously told the BBC “it's quite a challenge to keep a mask on for prolonged periods of time”.

“Research shows compliance with these recommended behaviours reduces over time when wearing face masks for prolonged periods,” added Dr Jake Dunning from Public Health England.

If the virus is lurking on the outside of a mask, a wearer may contaminate their hands when they go to take it off.

Many may also assume masks alone will keep them virus-free.

“People may have a false sense of reassurance and thus pay less attention to other behaviours key to reducing transmission such as social distancing and hand washing,” said Professor Susan Michie from University College London.

Dr Dunning added: “Face masks play a very important role in clinical settings, such as hospitals.

“However, there is very little evidence of widespread benefit from their use outside of these clinical settings.”

What is the coronavirus?

The coronavirus is one of seven strains of a virus class that are known to infect humans.

Others cause everything from the common cold to severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars), which killed 774 people during its 2002/3 outbreak.

The coronavirus tends to cause flu-like symptoms, including fever, cough and slight breathlessness.

It mainly spreads face-to-face via infected droplets expelled in a cough or sneeze.

There is also evidence it may be transmitted in faeces and can survive on surfaces.

In severe cases, pneumonia can come about if the infection spreads to the air sacs in the lungs.

This causes them to become inflamed and filled with fluid or pus.

The lungs then struggle to draw in air, resulting in reduced oxygen in the bloodstream and a build-up of carbon dioxide.

The coronavirus has no “set” treatment, with most patients naturally fighting off the infection.

Those requiring hospitalisation are offered “supportive care”, like ventilation, while their immune system gets to work.

Officials urge people ward off the coronavirus by washing their hands regularly and maintaining social distancing.