Coronavirus: Study suggests people should stay 8m apart for social distancing, but not everyone is convinced

New research has opened up a debate about the extent to which we should be social distancing amid the coronavirus outbreak.

Boris Johnson has enforced draconian measures that prevent Britons from leaving their home except for “very limited purposes”.

When people do venture out for “basic necessities” or to exercise, officials stress we must maintain a social distance of two metres (6.5ft) from those we do not live with.

This is thought to protect us from the coronavirus, which mainly spreads face-to-face via infected droplets expelled in a cough or sneeze.

Early research suggests the infection is mild in four out of five cases, however, it can trigger a respiratory disease called COVID-19.

A scientist from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) did not specifically analyse the coronavirus, but argued “gaseous clouds” emitted due to a variety of airway infections can reach up to 8.2 metres (26.9ft).

Another expert has questioned whether this “cloud” is still a threat beyond two metres, arguing if that was the case, “everybody would be infected”.

The coronavirus is thought to have emerged at a seafood and live animal market in the Chinese city of Wuhan at the end of last year.

It has since spread into 180 countries across every inhabited continent.

Latest coronavirus news, updates and advice

Live: Follow all the latest updates from the UK and around the world

Fact-checker: The number of COVID-19 cases in your local area

Explained: Symptoms, latest advice and how it compares to the flu

Since the outbreak was identified, more than 941,900 cases have been confirmed, of whom more than 195,900 have “recovered”, according to Johns Hopkins University.

Incidences have been plateauing in China since the end of February, and the US and Europe are now the worst-hit areas.

The UK had seen 33,718 confirmed cases and 2,921 deaths, according to government figures released on Thursday.

Globally, the death toll has exceeded 48,200.

Respiratory droplets ‘can travel up to 8m’

As far back as the 1930s, scientists have isolated droplets emitted when a person coughs or sneezes.

Research suggested that large droplets settle faster than they evaporate due to gravity, “contaminating the immediate vicinity of the infected individual”.

When small droplets transition from the warm, moist airways to the cold outside world, they are thought to evaporate quickly.

This leaves residual particles made of the dried material from the original droplets, known as aerosols.

When it comes to the coronavirus, the MIT scientist Dr Lydia Bourouiba argued “arbitrary droplet size cutoffs may not accurately reflect what actually occurs with respiratory emissions”.

She added droplets are accompanied by “a multiphase turbulent gas cloud”.

Moist and warm, this cloud may allow droplets to “evade evaporation” from “a second to minutes”.

These clouds also have a “forward momentum” that “propels” the droplets forwards.

“Given various combinations of an individual patient’s physiology and environmental conditions, such as humidity and temperature, the gas cloud and its payload of pathogen-bearing droplets of all sizes can travel 23-to-27ft (7-to-8m),” Dr Bourouiba wrote in the journal JAMA.

‘Everybody would be infected’ if the coronavirus travelled 8m

While another expert agrees pathogens like the coronavirus may travel some distance, it is unclear whether the “cloud” is capable of causing infection at 8m.

Dr Paul Pottinger, from the University of Washington, said: “For me, the question is not how far the germs can travel, but how far can they travel before they're no longer a threat.

“The biggest threat, we think, with the coronavirus is actually the larger droplets. Droplets of saliva, snot, spit.

“Droplets that almost look like rain, if you will, when someone sneezes.”

These droplets are thought to be sufficiently large that gravity acts on them.

“Usually, within about 6ft of leaving somebody's body, those larger, more infectious droplets will drop to the ground,” said Dr Pottinger.

“That's where the 6ft rule comes from.”

If the coronavirus were infectious at up to 8m, Dr Pottinger believes far more people would be suffering its tell-tale fever and cough.

“It takes a certain number of viral particles, we call them ‘virions’ or individual viruses, to actually get a foothold inside the body and cause that infection to get going”, he said.

“Now, we don't know exactly what that number is, but it's probably more than a single virus.

“If you think about it, if this [coronavirus] really traveled very efficiently by air, we wouldn't be having this conversation.

“Everybody would know it's true because everybody would be infected.”

While questions remain unanswered, Dr Bourouiba believes her research supports the use of masks in warding off the coronavirus.

“Flimsy masks are not going to protect from inhaling the smallest particulates in the air because they do not provide filtration,” she told the BBC.

“But they would potentially divert the cloud that is being emitted with high momentum to the side instead of forward.”

The effectiveness of masks has been debated, with one expert arguing there is “little evidence of widespread benefit” outside of hospitals.

Following Dr Bourouiba research’s, a panel that advises the World Health Organization (WHO) is due to meet virtually in the next few days to discuss if it should change its advice around masks.

The WHO currently states “if you are healthy, you only need to wear a mask if you are taking care of a person with suspected [coronavirus] infection”.

It advises those who are coughing or sneezing to wear a mask, a recommendation echoed by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The panel’s chair Professor David Heymann, from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, said: “As always when new evidence becomes available, WHO will be considering its face mask policies as a routine activity this week and next.

“Recommendations will be taken from many different advisory groups, including the external advisory group that I chair, and then WHO will decide if there is enough evidence to merit any changes in policy.”

He added the decision will likely cover how masks are used by healthcare workers in combination with other personal protective equipment and for those showing signs of the coronavirus.

The WHO recommends people stay “at least one metre (3.2ft)” from “anyone who is coughing or sneezing”.

UK government officials, however, advise two metres.

Professor Heymann previously said two metres is likely “reasonable”, but stressed it depends on “the force of speaking, and if you cough or sneeze”.

What is the coronavirus?

The coronavirus is one of seven strains of a virus class that are known to infect humans.

Others include the common cold and severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars), which killed 774 people during its 2002/3 outbreak.

While the coronavirus mainly spreads via coughs and sneezes, there is also evidence it can be transmitted in faeces and urine and survive on surfaces.

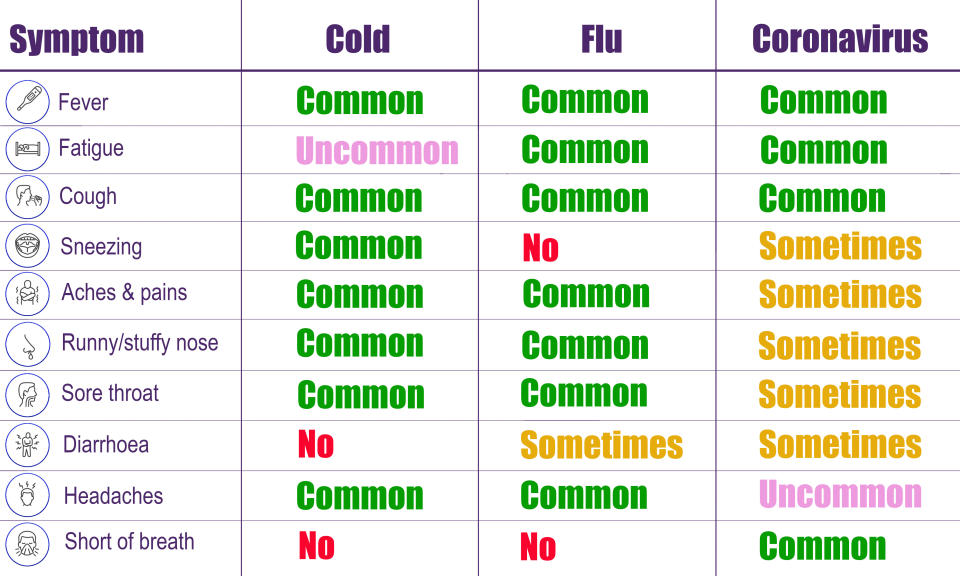

Symptoms tend to be flu-like, including fever, cough and slight breathlessness.

In severe incidences, pneumonia may come about if the infection spreads to the air sacs in the lungs, causing them to become inflamed and filled with fluid or pus.

The lungs then struggle to draw in air, resulting in reduced oxygen in the bloodstream and a build-up of carbon dioxide.

The coronavirus has no “set” treatment, with most patients naturally fighting off the infection.

Those requiring hospitalisation are offered “supportive care”, like ventilation, while their immune system gets to work.

As well as social distancing, officials urge people ward off the infection by washing their hands regularly.