The world’s ghost towns – before and after they were abandoned

Haunted histories

Edward Magele/CC BY 3.0 and Marcos Gittis/Alamy Stock Photo

Every ghost town was once a thriving community, but for various reasons these same communities abandoned them, leaving behind deserted settlements that echo of times past. From eerie ex-mining settlements to villages vacated because of war, these ghost towns have fascinating pasts and mysterious presents.

Read on to see what the world's best-known ghost towns looked like in life, and what they look like now...

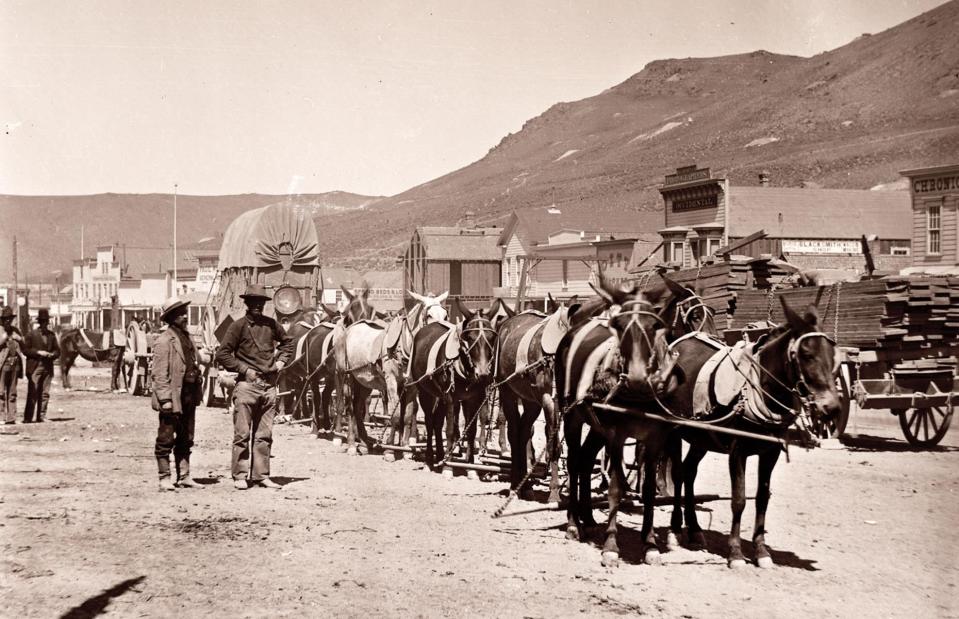

Then: Bodie, California, USA

California State University, Chico, Meriam Library Special Collections

Gold was first discovered in the Californian town of Bodie in 1859, but it wasn’t until mines to the north and east were exhausted that miners started emigrating to the region in large numbers. By the 1870s, when this picture was taken, the town had a population of around 10,000 people.

Miners and businessmen rubbed shoulders with gunslingers and gamblers, and Bodie quickly gained a reputation as a so-called 'shooters town', where Wild West-style gun fights were alarmingly common.

Now: Bodie, California, USA

eye35.pix/Alamy

Major mining operations ended in 1915 and smaller-scale efforts ceased in the early 1950s, after which Bodie was slowly abandoned as residents moved on to more temperate and prosperous towns. The town became a National Historic Landmark in 1961 and in 2008 the Bodie Foundation was created to ensure that the town be preserved in a state of 'arrested decay'.

Today, more than a hundred original buildings remain as an eerie reminder of the Wild West way of life, including the creaking Methodist church, old bank building and the jail.

Then: Plymouth, Montserrat

Patrick Robert/Sygma/CORBIS/Sygma via Getty Images

Montserrat is a tiny overseas territory of the United Kingdom in the Leeward Islands in the Caribbean. It was colonised by Irish settlers in 1632, earning it the nickname 'The Emerald Isle of the Caribbean', and its capital Plymouth was founded in the 1700s. In modern times Plymouth long served as the island's main port and boasted its only international airport.

This photo of the town’s War Memorial and Clocktower, built to commemorate the Montserratians who died in the First and Second World Wars, was taken in the 1970s.

Now: Plymouth, Montserrat

david sanger photography/Alamy

Today Plymouth lies abandoned and buried under ash after the previously dormant Soufriere Hills volcano erupted in 1995 and then again in 1997. Around 4,000 residents were evacuated to the north of the island and an exclusion zone was set up around the buried city, which quickly became known as 'the Pompeii of the Caribbean'.

Plymouth technically remains the capital of Montserrat – the only ghost town in the world to hold that bizarre distinction. A new capital is currently under construction at Little Bay in the far north of the island.

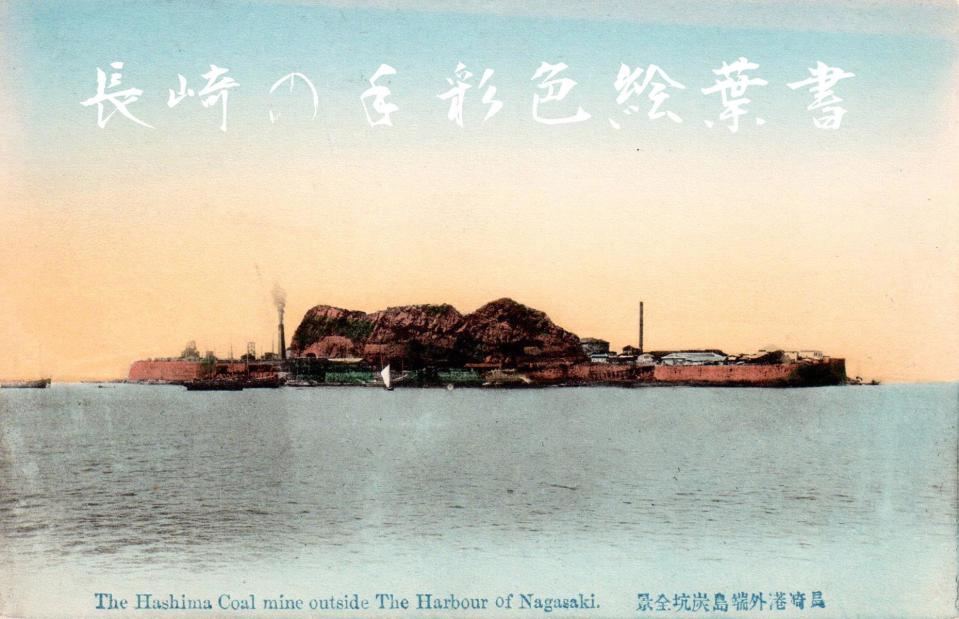

Then: Hashima Island, Japan

Public domain/Wikimedia Commons

Located just nine miles (15km) off Nagasaki, Hashima Island became a hub for the Japanese coal industry when Mitsubishi bought the island in 1890 and began extracting coal from undersea mines. Despite taking up a paltry 16 acres, it nevertheless supported a population of more than 5,000 in its heyday.

Half the island was devoted to the workings of the mine, the other to residential space including apartments, two schools, restaurants, shops, a public bath, a hospital and a Shinto shrine.

Now: Hashima Island, Japan

Hemis/Alamy

When Japan’s energy needs changed and the demand for coal declined, Mitsubishi closed the mine in 1974. Within months the workers left the facility and Hashima became a ghost island.

The island featured as the lair of Javier Bardem’s character in the James Bond film Skyfall and is now a popular tourist attraction. Since 2009, tourists have been able to land on the island and look out across the crumbling buildings and infrastructure from three different observation decks.

Then: Craco, Italy

Public domain/Wikimedia Commons

Life was never particularly easy in the southern Italian town of Craco, surrounded by sun-baked badlands a little way south of Matera. It was caught up in the upheaval surrounding the battle for Italian unification in the 19th century, and after the Second World War many of the town's young and able citizens left to start new lives in places like America and Australia.

By 1960, around the time this photo was taken, the town's residents were mostly the elderly and infirm.

Now: Craco, Italy

Vito Arcomano/Alamy

The final nail in the coffin came when a series of violent earthquakes and landslides saw the precarious hilltop town deemed uninhabitable. In 1963 most of the residents were moved to a settlement in a nearby valley and in 1980 it was abandoned altogether.

Today the only signs of life are tourists in hard hats on guided tours and the weeds sprouting from the crumbling buildings.

Then: Grytviken, South Georgia

Frank Hurley/Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge/Getty Images

In its heyday in the early 20th century, Grytviken on the subantarctic island of South Georgia was an extremely gruesome place. It was here that whalers pulled their catches onto the shore and processed them, slicing away the skin and fat in a stomach-churning task known as 'flensing', pictured here in the 1910s.

In the first full season of whaling at Grytviken, humpback whales were so numerous that the whalers could catch as many as they pleased without even leaving the bay.

Now: Grytviken, South Georgia

Robert Wyatt/Alamy

In just 60 years more than 54,000 whales were processed at Grytviken. But by the middle of the 20th century demand for whale oil was dropping and whale stocks were depleting, so in 1964 the whaling plant was closed for good.

Today the plant lies derelict and abandoned, a common stop-off point for visitors who come to the island to visit the grave of Antarctic explorer Ernest Shackleton, who died of a heart attack while moored just off shore.

Then: Wittenoom, Western Australia, Australia

Philip Schubert/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

Wittenoom was once a thriving mining town in Western Australia’s Pilbara region, about a 15-hour drive northeast from Perth. At its height the town had a population of 20,000 people, with 7,000 working directly in the mine. But the town held a deadly secret.

They were mining and milling blue asbestos, the most dangerous type of asbestos, and transporting the processed fibres in open trucks. In this photo taken in 1962, the asbestos dust from the bagging room is casting a blue haze over the area.

Now: Wittenoom, Western Australia, Australia

Alan Bilsborough/Alamy

The mine was closed in 1966, partly because the operation had become less profitable. Piles of contaminated mining waste were left lying about the town, and the government degazetted it in 2007 and removed it from all maps to discourage people from visiting.

In September 2022 the last resident of Wittenoom – the largest contaminated site in the southern hemisphere – was finally evicted, and campaigners hope a clean-up will finally begin. To date, more than 2,000 miners, residents and family members have died of asbestos-related diseases.

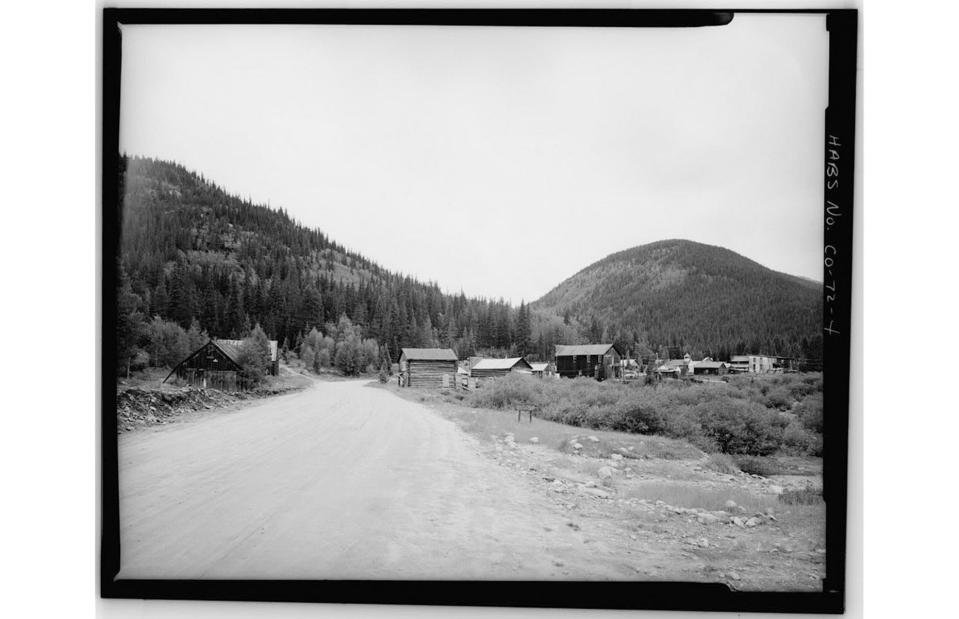

Then: St Elmo, Colorado, USA

Historic American Buildings Survey/Library of Congress

Incongruously named after a romantic 19th-century novel of the same name, St Elmo quickly shed any pretensions at romance when gold and silver were discovered in the area in the 1880s and 2,000 mainly male miners set up camp in town. The main street became a strip of saloons, dance halls and bawdy houses much like those in other towns of the era – though you might not know it from this photo taken in the 1930s.

The town received a boost when the completed Alpine Tunnel connected it to the Denver, South Park and Pacific Railroad.

Now: St Elmo, Colorado, USA

Stephen Saks Photography/Alamy

At the height of the mining boom there were over 150 patented mine claims in the St Elmo area. But as those claims were exhausted, the population dwindled.

When the railway line was closed in 1922 it is said that St Elmo's remaining population rode the last train out of town and never came back. Today St Elmo is one of the most accessible and best-preserved ghost towns in the west, with 43 buildings remaining pretty much as they were when abandoned, including a saloon, the courthouse, the jail, shops and private homes.

Then: Humberstone, Chile

Biblioteca Nacional de Chile

For a time between the 1880s and 1930s the mining town of Humberstone, high in the Atacama Desert in Chile, was the saltpetre capital of the world. Known scientifically as potassium nitrate and colloquially as 'white gold', it was an essential ingredient in the fertiliser that Europe's industrialising countries needed to grow food for their expanding populations.

Here we see the machinery and pans used for saltpetre crystallisation at work in 1889, when saltpetre accounted for up to 80% of Chile's exports and up to 60% of its fiscal revenue.

Now: Humberstone, Chile

Stuart Gray/Alamy

When German chemists developed a synthetic substitute during the First World War, the need for Chilean saltpetre plummeted and after a period of modernisation the facility at Humberstone was finally abandoned around 1960. The exodus took place so rapidly that much of the town was frozen in time, its preservation helped by the dry desert air.

In 2005, Humberstone was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and today remains an intriguing time capsule of what was once one of the most important – and lucrative – mines in the world.

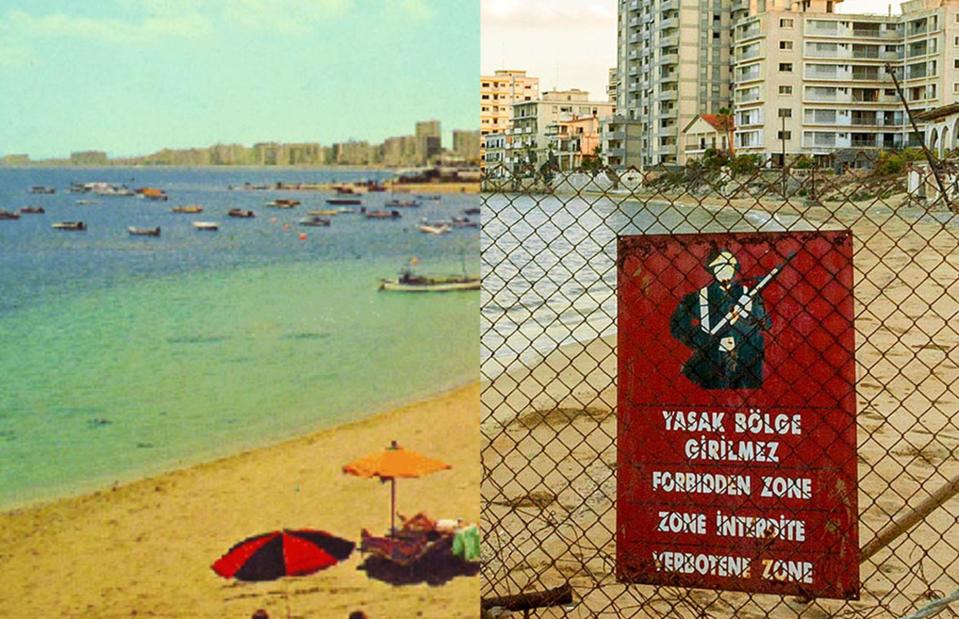

Then: Varosha, Cyprus

Edward Magele/CC BY 3.0

With its golden beaches, sparkling waters and buzzing nightlife, the dazzling beach resort of Varosha in Cyprus was once known as 'the Las Vegas of the Mediterranean'. In the mid-20th century it was one of the places to be seen for Europe's rich and famous and for a time the resort welcomed the likes of Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, as well as iconic French superstar Brigitte Bardot.

Now: Varosha, Cyprus

Marcos Gittis/Alamy

Varosha’s glory days were abruptly cut short in July 1974 when longstanding Greek-Turkish tensions came to a head. An Athens-backed coup saw the Turkish army invade the island to protect Turkish Cypriots from feared ethnic violence.

Everyone but the Turkish military was forbidden from entering Varosha, and today buildings in the once-booming town lie derelict and abandoned. In recent years Turkish citizens have been allowed to visit the beach, but the crumbling infrastructure remains off limits due to safety concerns.

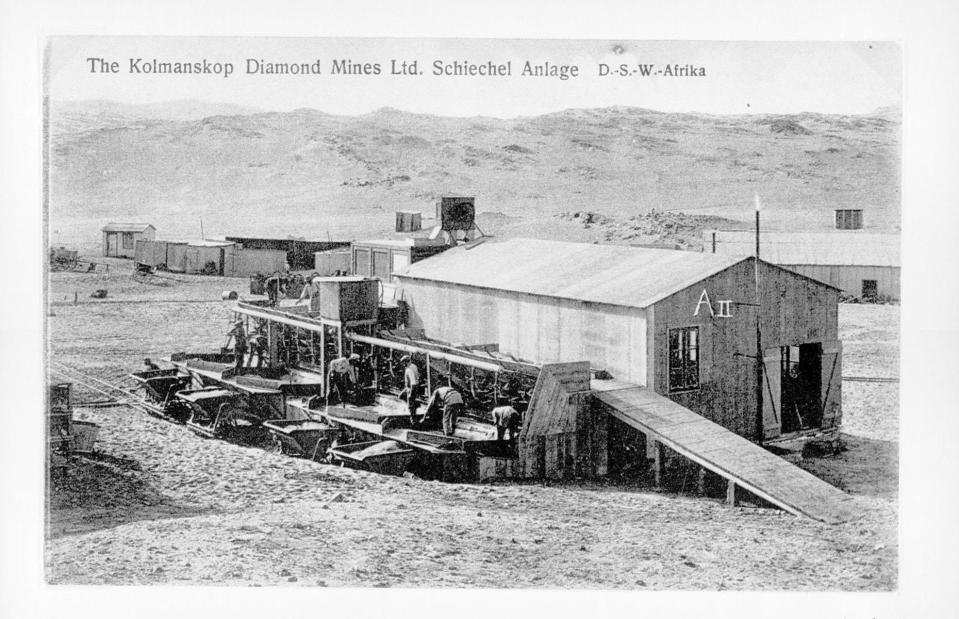

Then: Kolmanskop, Namibia

Bildarchiv der Deutschen Kolonialgesellschaft, Universitätsbibliothek Frankfurt am Main (A_0MM_5634)

A chance discovery by a Namibian rail worker clearing tracks in 1908 set off a chain of events that would transform a lonely empty speck in the Namib desert into one of the richest places on the entire African continent. Zacherias Lewala had discovered diamonds, and once word got out prospectors descended on the area.

By 1912 the newly-formed town of Kolmanskop was producing a million carats a year and had become an oasis of luxury and wealth, as well as an unlikely cultural hotspot.

Now: Kolmanskop, Namibia

Peter Sumner/Alamy

With Kolmanskop’s prospectors simply picking up diamonds where they lay, the German colonial authorities who controlled Namibia at the time stepped in and gave prospecting rights to a single Berlin-based company. When more diamonds were found to the south the townspeople left in droves, abandoning their homes and possessions.

By 1956 the mines were exhausted and Kolmanskop abandoned. The dunes quickly reclaimed what was theirs, creeping through the doors of the buildings and filling them with sand.

Then: Ocean Falls, British Columbia, Canada

Keystone/Getty Images

Tucked into Cousins Inlet amid a network of winding fjords, Ocean Falls in British Columbia is at least a day’s journey from Vancouver, but its waterfront location always provided ample hydroelectric power. The Bella Coola Pulp and Paper Company opened a plant here in the early 20th century and for many years high demand for paper meant that industry thrived in the town.

This photo taken around 1935 shows a worker sorting logs that are destined to become paper.

Then: Ocean Falls, British Columbia, Canada

A.Davey/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

In its heyday up to 3,500 people called Ocean Falls home. But by the late 1960s costs were rising and many of the buildings were dated, so operations started winding down. By the early 1980s only around 70 residents remained.

Today much of the town lies in ruins, including the deserted Martin Inn, once one of the largest hotels on Canada’s west coast. The inn – along with the town itself – remains a popular destination for urban adventurers who come to explore the abandoned husks that sit decaying in Ocean Falls' notoriously rainy weather.

Then: Belchite, Spain

Sueddeutsche Zeitung Photo/Alamy

The small Aragonese town of Belchite, 28 miles (45km) south of Zaragoza, was founded in 1122 to defend the frontier between the Christian kingdoms in the north and the Muslim Moorish kingdoms to the south. In 1937 Belchite found itself on the frontline again, this time in the Spanish Civil War, when a battle between Republican forces and Nationalists led by General Franco killed thousands and left the town in ruins.

Such was the devastation that journalist Cecil D Eby described what was left as "less a town than a nasty smell".

Now: Belchite, Spain

David Chapman/Alamy

When Franco finally retook Belchite in 1938 he ordered that the town should not be rebuilt. He wanted the scarred ruins to remain as a monument to war – and to the consequences of opposing him.

Today Belchite looks largely as it did back then: battered, brutalised and abandoned to the elements. But rather than a tribute to one man’s power, visitors who take a guided tour of the site see instead a bleak reminder of the brutality of fascism and the folly of war.

Then: Pyramiden, Norway

Buiobuione/CC BY 4.0/Wikimedia Commons

It was the Swedes who first discovered coal on Svalbard, a bleak archipelago situated between Norway and the North Pole. But after the islands were ceded to Norway as part of the Svalbard Treaty of 1925 – with the proviso that other nations could continue to fish and mine there – the Swedes sold their coal mine at Pyramiden to the Russians.

By the 1950s it was a mini Soviet Union in the heart of the Arctic, home to 2,500 people – more than live in Svalbard's capital, Longyearbyen, today.

Now: Pyramiden, Norway

antimo andriani/Alamy

Mining continued at Pyramiden until 1998. The town had survived the collapse of the Soviet Union, but shrinking coal reserves and a disastrous 1996 plane crash at Operafjellet that caused 141 Russians to lose their lives saw it suddenly abandoned.

Nearly 30 years later it looks much as it did then, right down to the political murals and busts of Lenin, providing visitors with a glimpse into Soviet-era life and culture.

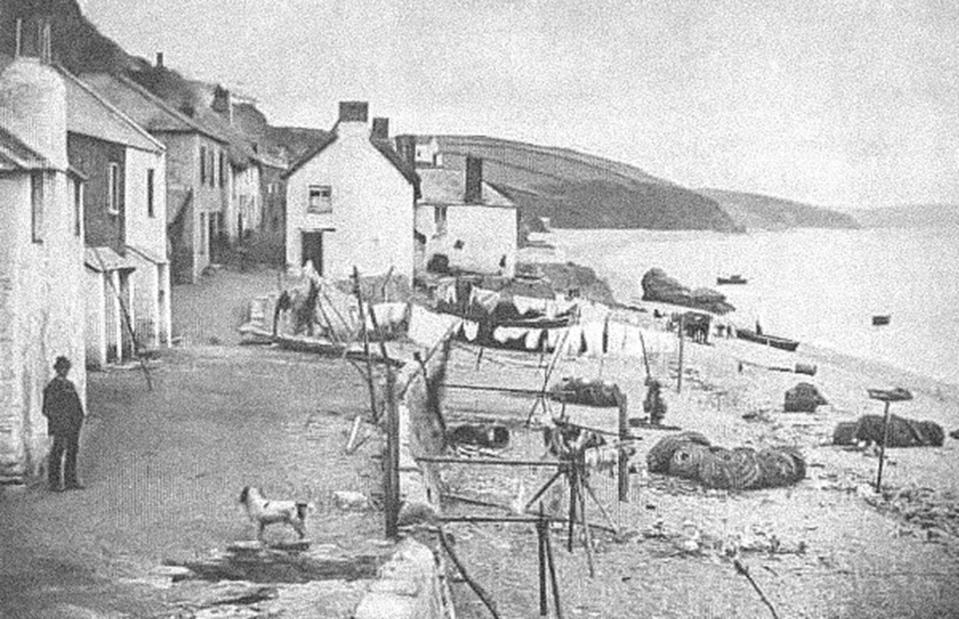

Hallsands, England, UK

City of Plymouth Archives and Records/Public domain/Wikimedia Commons

Around the time this photo was taken in 1885 the atmospheric village of Hallsand on the Devon coast had 37 houses, a pub called the London Inn and a population of 159. The villagers depended on fishing and catching crab for a living – a hazardous business that came with erratic earnings and a high chance of being lost at sea.

Nevertheless it was a close-knit community where everyone, including women and children, helped bring in the day's catch.

Hallsands, England, UK

Marc Hill/Alamy

That community would be lost forever when the Admiralty began dredging for shingle just off the village in the 1890s. By 1900 the level of the beach had started to fall, and in the autumn of that year part of the sea wall was washed away by storms.

The erosion continued slowly until the night of 26 January 1917, when gale-force winds and high tides breached Hallsands' defences and the village finally fell into the sea. No one was hurt, but every house vanished except one. It was owned by Elizabeth Prettyjohn, who refused to leave and lived there with her chickens until her death in 1964.

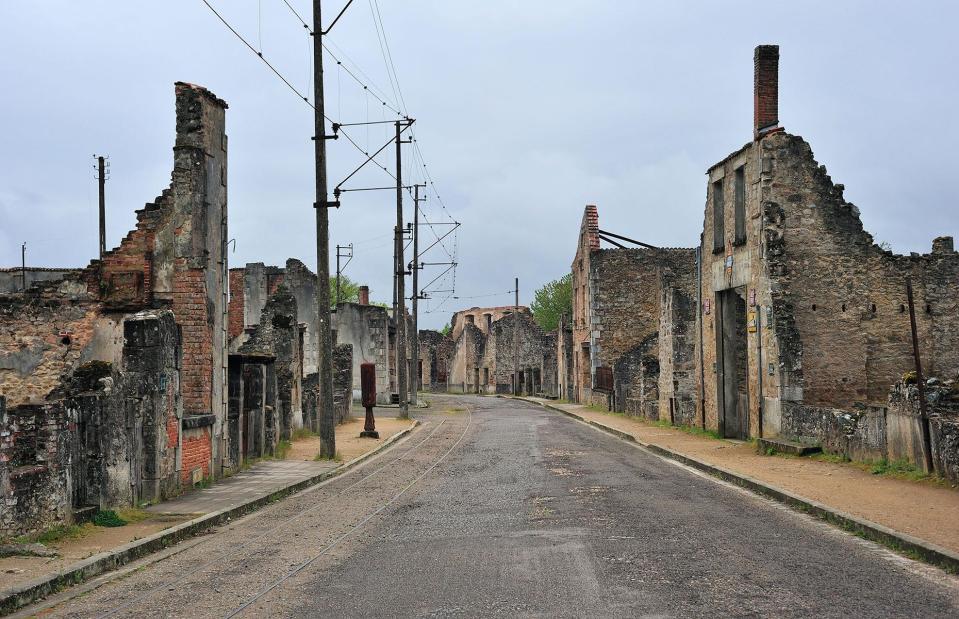

Then: Oradour-sur-Glane, France

AFP via Getty Images

Before the Second World War, Oradour-sur-Glane was a quiet rural community located near Clermont-Ferrand in Central France. That all changed on 10 June 1944 when SS soldiers rounded up the roughly 650 people in the village – many of them refugees – and massacred them.

The men were locked into a barn, the women and children into the church, and then both buildings were set on fire. Here we see a funeral procession through the town to commemorate those lost shortly after.

Now: Oradour-sur-Glane, France

Arterra Picture Library/Alamy

Only seven people survived the massacre: five men protected by fallen bodies, a woman who escaped through the church window and a child who managed to escape during the round-up. In 1946 the French government declared that the burnt-out remains of Oradour-sur-Glane should be left untouched as a memorial to those lost that lost their lives – a purpose it continues to serve to this day.

Now discover more of the world's most fascinating ghost towns