What's Stone Island's Secret?

Subcultural credibility is a delicate thing for the fashion brands that become part of a given group's uniform. Once you’ve been adopted, the question goes, how do you maintain and strengthen that relationship with that subculture? And how do you use it to move more units?

Some brands will attempt to tweak things aesthetically, churning out designs they think the new fanbase wants. Others will try to cater to interests outside of fashion—maybe a concert series. Others still will lean into marketing, re-tuning advertising to try to capture more cool kids. Sometimes, it works. More often than not, though, the play for credibility backfires, alienating the very folks it was intended to entice.

So, what do you do? For Stone Island, the answer is simple: Nothing.

“We never take ideas from the street,” says Carlo Rivetti, who first became involved with Stone Island in 1983 and has led the company since 1993. “I always say that if something is already on the street, someone has already done it.”

Stone Island was founded in Ravarino, Italy, in 1982 by Massimo Osti, the pioneering designer and businessman who helped usher in a new approach to sportswear by blending textile innovation with functional, often military-inspired garments. (Osti also founded the label C.P. Company in 1971, paving the way for the establishment of even-more-experimental Stone Island.) Rivetti’s family company GFT quickly acquired a 50 percent stake that later increased to the entirety of the company. By 1993, Rivetti had formed his own company with his sister Cristina and took over Stone Island. Osti parted ways with the brand in 1994.

At this point, Stone Island had already established a reputation for technical prowess, functional know-how, and, of course, fabrics that defied the imagination. “Tela Stella.” “Raso Gommato.” “Rubber wool.” Thermosenstive and reflective fabrics. These all became hallmarks of the label’s output.

Those unconventional fabrics found a subcultural following pretty much from the start. First, it was the fashion-obsessed paninari of Italy, who adopted Stone Island as part of their uniform in the ‘80s. By the ‘90s, the brand had made the journey to Britain, where football-loving casuals wore Stoney—as fans lovingly call it—to root for their clubs and engage in the odd bit of hooliganism while Britpop stars wore it for stadiums full of screaming fans. In the early 2000s, the brand made another long journey, this time to the U.S. and Canada where it was winding its way into hip-hop culture. Now, it’s a staple in the grime scene in London, the streetwear scene in Los Angeles, the fashion industry in New York, and untold other cultural nooks and crannies.

"I have worked in brand strategy for my whole life, and I have thought long and hard about what brands have this capacity that this brand has. There are really very few,” says Robert Triefus, who logged extensive time at Calvin Klein and Giorgio Armani—not to mention his most recent 15-year stint at Gucci—before joining on as CEO of Stone Island in May of 2023.

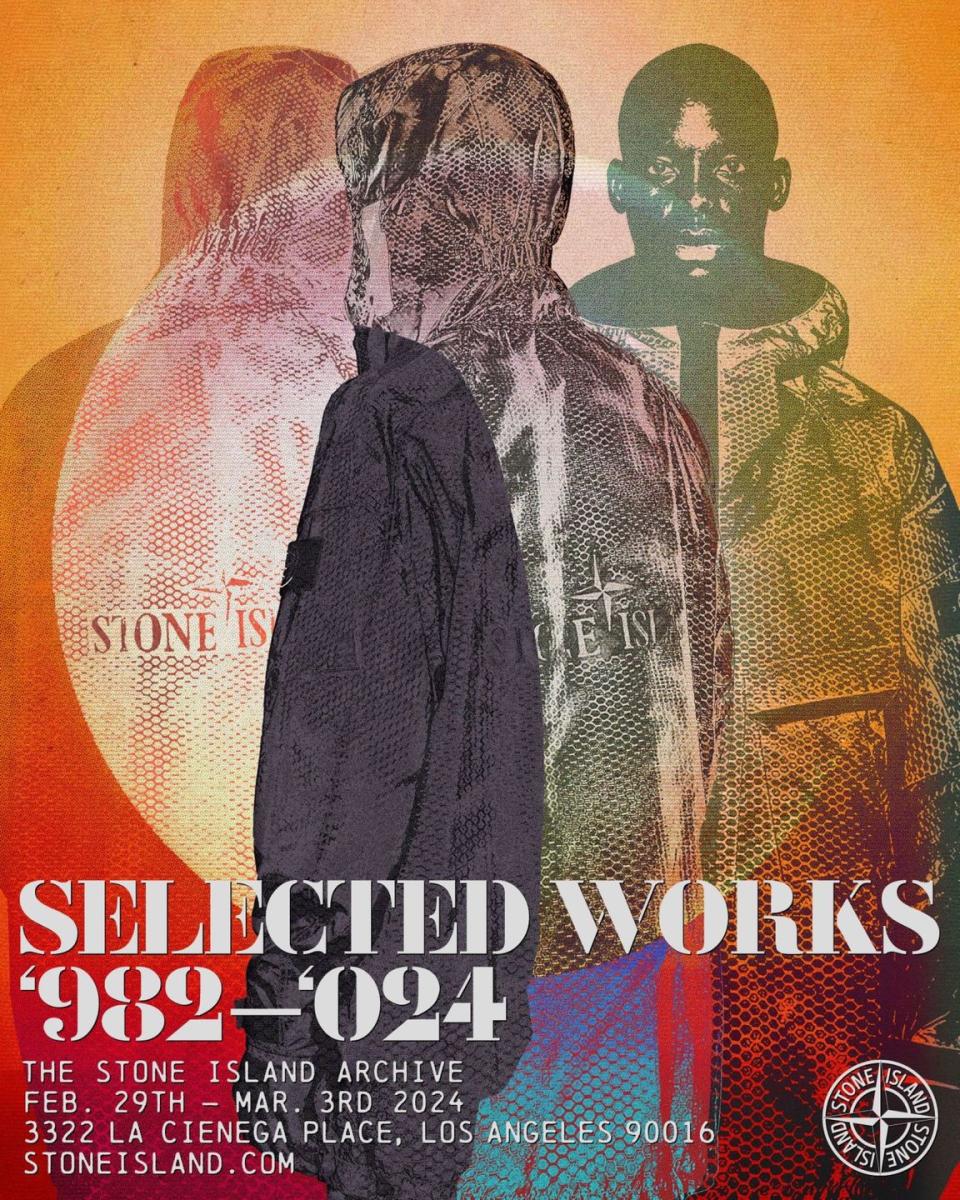

“I'm British, originally, and I grew up with Stone Island,” he tells me inside the cavernous space in Los Angeles where the exhibition Selected Works: ‘982-‘024 took place earlier this month. “I was very interested to kind of get under the bonnet and try to understand what is it that over 40 years has very organically allowed communities to bring themselves and adopt the brand.”

One thing that can’t be overlooked is the bang-on branding. The Stone Island badge—usually a fabric arm patch with a black background and a yellow-and-green compass in the center, though all sorts of different iterations and executions now exist—is a calling card and a nod to fellow enthusiasts. “We recognize each other when we walk in the street wearing this,” Rivetti says, gesturing at the Stone Island logo on his own jacket. “We look at each other and we recognize it. It is a sort of club.”

At the heart of the club, says Rivetti, isn’t an appreciation of branding but of what it represents. “Little by little, because now it’s 42 years, we were able to build a community,” he explains in a breezy stairwell outside the space, flanked by his son Silvio and wife Sabina. “But I think that the first community is the factory in Ravarino, because we are a small village. The people that enter the company, they work for us all their life. We do things that are more or less unique. We are able to mix technology, research, innovation, function. And I think that the final customers—and they know our product very well—are fascinated by our capability.”

“So the idea is always to push the boundary,” he says. “And the one that I prefer is ‘impossible.’ When someone says to me, ‘This is impossible,’ we will do it. And if you don’t look outside—if you look inside, to the capability of the people working in the company—it’s very easy to maintain the pureness of the DNA of the brand.”

“We never chase trends,” Silvio offers. “I think the key aspect is to spread the culture. We have values to communicate, and stories, and it's a matter of amplifying those messages—those values—to a wider audience.”

“We say that Stone Island does not adopt,” Sabina adds. “Stone Island gets adopted.”

“It's been always very organic and natural,” says Silvio.

“Si,” says Carlo.

You Might Also Like