Will Tom Cruise Be the Last Real Movie Star?

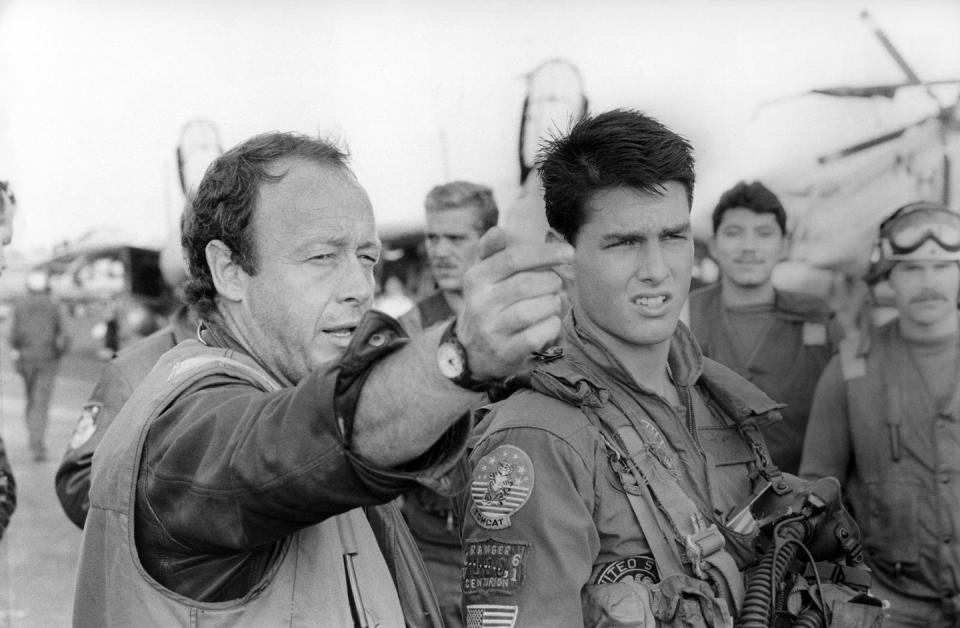

This summer, Tom Cruise turns 60 — to the astonishment of us all. His face may be a little sleeker and puffier, the nose and jawline discreetly modified, the hair richly ungrey. But Tom Cruise is the Eighth Wonder of the physical world. The bod is tight. The buttocks are granite. The gaze is focused. The teeth are dazzling. The career is strong. Basically, he looks better than most 40-year-olds. He doesn’t look that different from the boyish Lt Pete “Maverick” Mitchell, the speedy US Navy Flyer he played in the legendary action spectacular Top Gun, in 1986, that propelled him into ionospheric celebrity. And, of course, he’s in this summer’s sequel, for which he walked the Cannes red carpet— Top Gun: Maverick, unselfconsciously doing much the same thing.

I watched Top Gun again the other day for the first time since it came out. What struck me was not so much the homoeroticism, based on the locker-room rapport between unclothed alpha males (“I’ve got a hard-on.” “Don’t tease me”), famously satirised by Quentin Tarantino in a monologue in the 1994 film Sleep With Me. Actually, it was the beach volleyball scene in which Maverick (Cruise) and Goose (Anthony Edwards) are winning handsomely and, every time they get a point, Cruise gives Edwards two resounding high-fives, up high and down low, with smacks that must have reverberated up the western seaboard like sonic booms. My own palms were flinching and tingling at the sheer machismo. Poor Edwards must have been in agony.

Tom Cruise is the last Hollywood icon standing, the last real movie star. In an age of franchises, intellectual property and superheroes, Cruise is the defiant survivor of a time when the currency was the superstars themselves, with their unchanging personalities and their professional duty to keep young and beautiful. Despite all the affection I have for the great man, he is a living embodiment of the theory that true stars don’t have something extra; they have, in fact, something missing, some weird gap or void into which the audience projects its desire.

From his early manhood in the 1980s, Tom Cruise could “open” a movie: he was an “above-the-title” star, that quaint phrase coming from an age of titles being spelt out on marquees. Most actors of Cruise’s age will have long since accepted their character roles as fathers or grandfathers. They will have taken mature “bearded” parts, like 44-year-old George Clooney in Syriana or 57-year-old Tom Hanks in Captain Phillips. Not Tom.

Actually, it’s not quite true to say that Tom Cruise doesn’t do beards. He grew a wild and straggly beard for Born on the Fourth of July, when he played the radically anti-war Vietnam veteran Ron Kovic; and he grew a neat, tailored beard, indicating wisdom and inner strength, for The Last Samurai, portraying a US cavalry officer in 19th-century Japan. But these were not ageing-process beards or silver-fox beards. And he has — for good-sport laughs — pretended to be fat and bald as a movie producer rocking out in triumph in the comedy Tropic Thunder. But, in each case, the point is that the fiercely attractive pretty-boy Cruise is obviously there underneath.

He has worked with the biggest directors in the business: for Steven Spielberg as the star of War of the Worlds, for Paul Thomas Anderson, playing the chillingly misogynistic seduction coach in Magnolia, and for Stanley Kubrick in Eyes Wide Shut, painfully exploring a marital crisis opposite his then-wife Nicole Kidman.

But he was always Tom Cruise, and there is something eerie in the way he has been box-office gold for over four decades. In the US domestic-revenue charts for 1985, newcomer Tom Cruise came in at number 15 (number one was Chevy Chase). In 1987, he slipped to 18 (the highest position that year was held by Steve Guttenberg, of the Police Academy movies) but took the top spot in 1988, knocking Guttenberg down to three. He came third in 1990 when Tom Hanks was in first place, and won bronze in 1994 when Wesley Snipes took gold. In 2005, Keanu Reeves was victorious, while Cruise hung in there at 12. The man has seen them come and go — Guttenberg, Chase, Jim Carrey, Bradley Cooper — but he has kept up with or outlasted them all.

The Cruise persists. And his co-stars from Top Gun, Edwards, Kelly McGillis and Meg Ryan, might now look older or different in the way that would be expected of normal human beings. But Tom is like a human action figure, and this is very largely because, 20 years ago, he shrewdly positioned himself as the star of what became an action franchise: the Mission: Impossible movies. Playing top agent Ethan Hunt, he takes on risky missions against shadowy bad guys, rides motorbikes, scales buildings, wears luxury watches, is lowered on wires into secure bank vaults to tap security codes into laptops, and free-climbs dangerous rocky outcrops. Cruise’s late-career genius was to identify that, if franchises were the way Hollywood was going, then he would control and be the franchise, the key constituent element. MI has become loved — and Cruise has become almost an honorary national treasure in the UK, for the way he has committed to using British production facilities.

In December 2020, The Sun released a leaked audio tape of Cruise haranguing crew members on Mission: Impossible 7 for breaking Covid rules. He yelled: “If I see you do it again, you’re fucking GONE!” With anyone else, the optics of that would have been too awful. It could have been a cancellation moment: a rich Hollywood bully humiliating British workers? But, actually, there was sympathy for him. Everyone I spoke to shrugged and said he was under a lot of pressure. And Covid rules were important.

Tom Cruise has grown on us all. I loved him in Magnolia, with his detestation of the journalist who presumes to question him about his family background. I loved him in Michael Mann’s thriller Collateral, where he played the (daringly) grey-haired killer being ferried around in the back of Jamie Foxx’s cab. I can never see this film without thinking of Cruise’s remarkable claim that, as a penniless wannabe actor in Manhattan in the early 1980s, he would persuade prostitutes to give him rides back through the Lincoln Tunnel to his family home in New Jersey. Which is to say — he would have had to persuade the prostitutes’ clients, because they were the ones with the cars. I can imagine young Cruise riding in the back, with the sex worker and driver upfront, these people having been cowed by the sheer force of his urgent, insecure personality: switching between the dazzling smile and the fierce look of determination: the monobrow, the jutting chin.

His life story is rather compelling: the father who abused the family. The mother who quietly woke Tom and his sisters at 4:30 in the morning when they were living in Ottawa, so that they could escape the violent pater familias and get over the border to the United States, where her family would effectively support them.

Then there was his hardworking, but fairly mediocre, academic career in high school (where he dreamed of being a pilot), which ended in him taking a role as Nathan Detroit in the school production of Guys and Dolls. A fellow student at the school happened to have a minor TV career, and her agent was in the audience — and he saw Tom’s star potential.

Nathan Detroit! What fascinatingly atypical casting. Not Sky Masterson, the more obviously romantic lead, but Nathan Detroit, the hassled domesticated guy. I would have loved to see Cruise in that singing role. Surely we can revive Guys and Dolls on the London stage and persuade him to do it again?

There also is the matter of his controversial attachment to Scientology, to which he was introduced by his first wife, Mimi Rogers, in which he then, allegedly, tried (and failed) to immerse his second wife, Nicole Kidman, and whose adherents and creepy functionaries are said to have made his third wife, Katie Holmes, feel very uncomfortable. This, too, should have turned everyone against him, long ago. But, strangely, it hasn’t. Partly, that is to do with it being a controversy of such long standing, predating social media by decades. Partly it is down to a secular-atheist view that Scientology is no sillier than any other faith, or that Cruise’s attachment is a quaint eccentricity, like being a Mason. But it is also something else — people now know that, as a young and naive neophyte in the religion, Cruise submitted to intimate tape-recorded “auditing” sessions and, perhaps eager to demonstrate his humility and self-criticism, he may have admitted to various thoughts and feelings disapproved of both by Scientologists and his future red-blooded male fanbase in Reagan’s America. Could it be that Scientologists and their peculiar leader, David Miscavige, have had a hold on their most famous recruit? Could it be that Tom Cruise’s intense, charismatically coiled and clenched address to the camera is a 40-year hostage video?

I wonder. At any rate, when Top Gun: Maverick comes out on Friday, I shall be first in line to see the great man take to the skies once again and to marvel at his career-long defiance of gravity.

'Top Gun: Maverick' is out in cinemas on 27 May; read Esquire's review here

You Might Also Like