Sonic Life: A Memoir by Thurston Moore review – nerd’s eye view

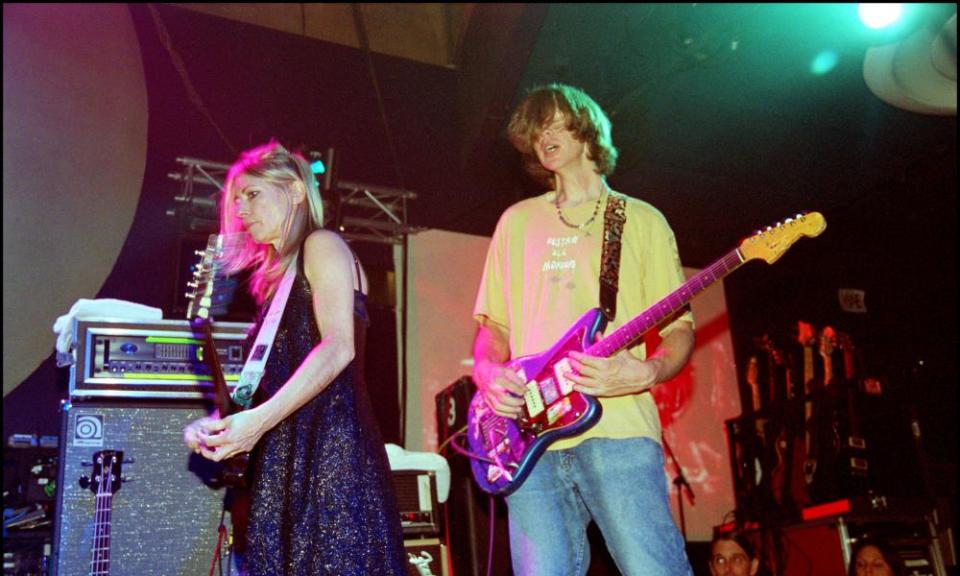

In 1978, the 19-year-old Thurston Moore left Connecticut for New York, intent on forming a band. There were a number of false starts – founded four years later, Sonic Youth didn’t really come into their own until their 1985 album Bad Moon Rising, the first in a string of releases that made them the most revered US indie group of the pre-Nirvana era – but, reading Sonic Life, it’s hard not to think it was probably only a matter of time: if anyone was born to lead the most revered US indie group of their era, it was Thurston Moore.

He appears to have come out of the womb with impeccable alt-rock taste. No embarrassing prepubescent flirtation with whatever the mid-60s US equivalent of the Wombles or Crazy Frog was for him; the first single that turns his head, aged five, is the Kingsmen’s garage-rock classic Louie Louie. By the end of the decade, he’s graduated to the Stooges, Can and Captain Beefheart. His first instinct on availing himself of an electric guitar is not to learn to play, but to start making the kind of fearsome atonal noise that regularly punctuated Sonic Youth’s oeuvre: the delight of his family’s neighbours at this development can be well imagined. Even after he gets to New York, his tastes mark him out: he’s forever the last man enthusing at gigs that have caused the rest of the audience to hurriedly leave, fingers in their ears.

This could come across as cooler-than-thou posturing, but it doesn’t. Moore is an unabashed nerdy enthusiast. He writes about music in a breathless gush of hyperbole that proves almost too infectious: fired up by his fervour, you find yourself scuttling to YouTube to check out, say, the forgotten no wave artist Boris Policeband, only to discover you too would have hurriedly departed his gig with your fingers in your ears.

Meanwhile, Moore’s depiction of pre-gentrification Manhattan’s post-punk bohemia is richly evocative and Sonic Life’s highlight. These pages somehow make a demi-monde of cockroachy apartments, terrible part-time jobs and gigs by artists so obscure they make Boris Policeband look like Harry Styles – Tone Death, Avoidance Behaviour, Borbetomagus – sound incredibly appealing. He rubs shoulders with Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring and Madonna (improbably enough, she briefly romances Moore’s friend Michael Gira, frontman of notoriously punishing noise band Swans), and finally experiences a musical eureka moment when he hears the deafening detuned guitars of composer Glenn Branca. Rapt once more while everyone else is storming the exits, he hits on the idea of applying the sound of Branca’s symphonies to songs: the blueprint for Sonic Youth.

Their career proves fascinating, not least because they pull off the difficult trick of becoming increasingly successful without compromise, even after signing to a major label: Nirvana signed to the same one precisely because it had let Sonic Youth do whatever they wanted. For a moment, Moore wonders if they might achieve huge mainstream fame in Nirvana’s wake, but Kurt Cobain’s suicide understandably rattles him, and not just because they’re friends. Offered an object lesson in being careful what you wish for, Sonic Youth settle happily into life as cult figures and elder art-rock statespeople, until it all goes suddenly wrong.

Which brings us to the rock memoir elephant in the room. Sonic Life arrives eight years after Girl in a Band, by Sonic Youth’s bassist and Moore’s ex-wife Kim Gordon, a cool, brutally honest and beautifully written autobiography overshadowed by her discovery of Moore’s six-year-long affair, which prompted both their divorce and the end of Sonic Youth’s 30-year career. In Sonic Life, Moore improbably breezes through the story of his infidelity and Sonic Youth’s split in two pages – you could suggest there’s something barbed about his explanation that the subject is too “intensely personal” to “capitalize on … here or anywhere”.

Related: Sonic Youth’s greatest songs – ranked!

But that feels par for the course: Sonic Life tells you a lot more about Moore’s record collection and gig-going history than Moore himself. We learn that his best friend at school was gay and harboured an unrequited crush on him and that Moore had a brief flirtation with teenage delinquency – pointlessly burgling a neighbour’s house under the aegis of a troubled schoolfriend – but the topics you would expect a memoir to dwell on don’t detain him. His family are shadowy presences, as are Sonic Youth’s guitarist Lee Ranaldo and drummer Steve Shelley. He doesn’t appear to have had any romantic life to speak of before meeting Gordon at 22, beyond a solitary brief fling. His father dies suddenly and unexpectedly in Moore’s teens; he writes less about it than a Cramps gig he goes to a month later.

Perhaps he’s just like that, or perhaps he’s being deliberately circumspect, keen to avoid being accused of score-settling in the wake of Girl in a Band. If so, he’ll probably succeed, but at the expense of making Sonic Life lopsided: it works better as a personal history of American alternative rock than a memoir per se. Which ironically brings Gordon’s book to mind, specifically a line that one suspects was rather pointed, about men’s inability to communicate: they found closeness, she suggests, “by focusing on a third thing that wasn’t them: music”.

• Sonic Life: A Memoir by Thurston Moore is published by Faber (£20). To support the Guardian and Observer, order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.