The male mental health crisis: What it's like to lose a twin to suicide

Warning: This article contains discussion of suicide.

“It was 19 April 2009, a lovely crisp day. I finished my night shift at 11am, went home and noticed lots of missed calls on my phone. I didn’t think anything of it and went for a shower, but when I got out there were more calls. Before I could even ring back, my dad was calling again and was on the phone in hysterics. ‘He’s done it,’ Dad said. The world stopped. My partner at the time came into the room and I blurted out: ‘Luke’s dead.'"

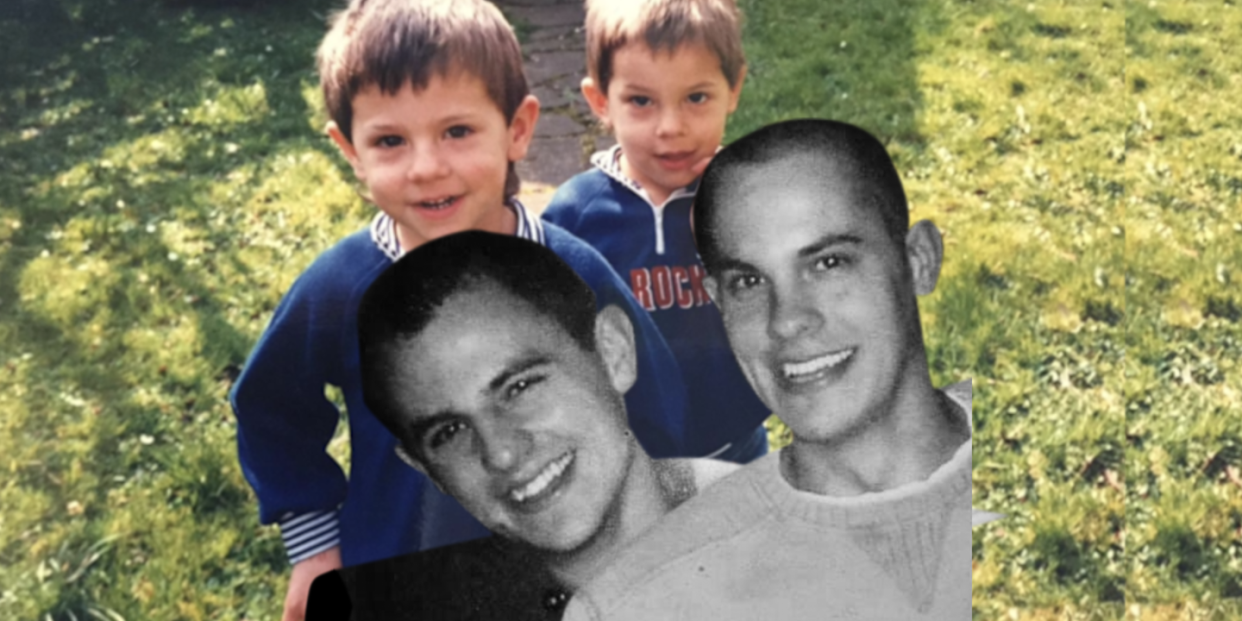

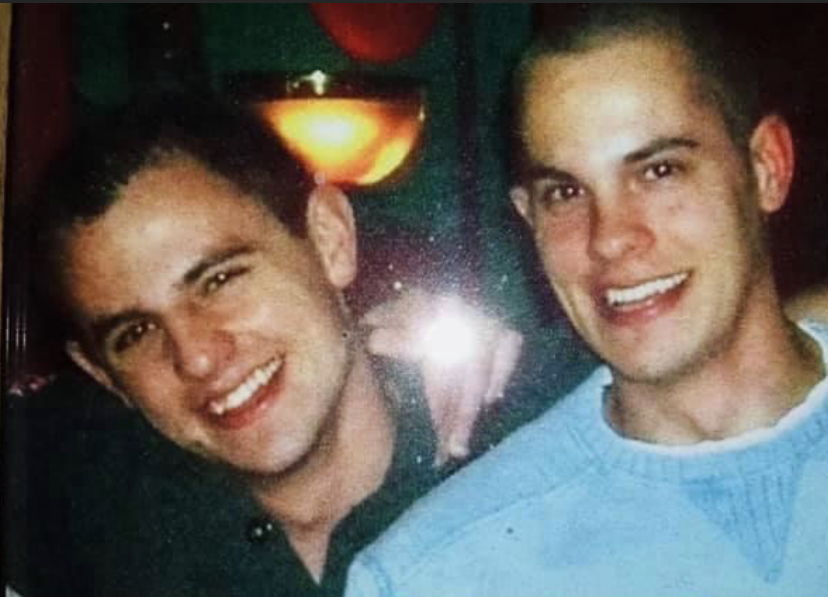

Growing up, twins Aaron and Luke Leventhal were inseparable. They had the same friends, hung out together after school and shared a passion for all things flying. They loved playing with remote control aeroplanes together.

As they matured into teenagers, though, differences started emerging. Aaron joined the RAF Air Cadets, while Luke preferred staying at home in his bedroom. Aaron spent his time studying after school, while his brother didn’t. Aaron tried to prompt Luke to join in more, but he wasn’t interested.

The brothers joined the Army in their late teens, something which initially helped Luke out of his shell, but after three years, he was missing his loved ones at home and was discharged when he opened up about feeling suicidal. Luke then joined the Army Reserves locally for a year, a time when his mental health deteriorated and he was making attempts to take his own life.

“One time he texted me saying: ‘I don't want to be in this life anymore.’ I was in a nightclub at the time and ran home to find him laid in bed,” Aaron, now 37, remembers. “I broke down and told him: ‘This is not healthy. We need to get to the bottom of this.’”

The family sought help for Luke, but he refused it. “We had the mental health nurses speak to him. We got the anti-depressants. He said he was taking them, but he wasn’t.” For Aaron and his family, it was heartbreaking to see. “I was always on edge waiting for him to do it again,” Aaron says.

After Luke had made numerous attempts on his life over a period spanning several years, on that crisp April morning in 2009, Aaron received the call he’d been dreading. His brother was gone. He was just 25 years old.

“For the first couple of years, I didn’t want to be here myself, to be honest. I was lost,” Aaron says. Slowly, however, he began to piece himself back together. Aaron believes that training to be an airline pilot, and fulfilling the dreams he and Luke shared as children, ultimately saved his life.

“I started flying small aeroplanes just a couple of months before [Luke died]. We used to sit at the end of the runway and watch planes. I remember him saying: ‘I can’t wait to fly with you’,” he recalls. When he finally achieved his goal, it was bittersweet. “We never got that. It was just too late,” Aaron says, pensively.

What played on Aaron's mind for a long time after Luke's death was that, despite his brother's previous suicide attempts, he appeared happy in the weeks before he took his own life.

The last time Aaron saw Luke, his twin was running up and down the stairs, excitedly setting up the new music system he’d recently bought. He’d paid for the system by selling his prized car, a blue Clio, about two weeks before. Aaron had found this odd at the time, but Luke had started a new job, was going out at weekends and seemed happy in himself, so he hoped that he was perhaps turning a corner.

The evening before his brother's death, Aaron received messages from Luke asking him to go on a night out, which he declined as he had to work. Coming home from his shift the next morning, the news that his brother was gone hit Aaron hard. Family members “blamed themselves” for Luke’s death, but nobody could have known what was coming.

“Since Luke's death, mental health nurses have told me that people with depression, if they’re going to [take their own lives], can hide it quite well. He probably had it set in his mind; he knew what was going to happen and he was happy that he was not going to be here much longer,” Aaron reflects.

“My brother hid it well, especially in the last few weeks. You really can’t tell what’s going on in someone’s head,” he says.

Now, Aaron is working to raise awareness and funds in aid of the charity Papyrus, which aims to prevent young suicide. He recently completed a charity challenge in South Wales, climbing the equivalent of the Mount Kilimanjaro Summit in 24 hours. “I don’t want to see another family go through what we went through, if we can save one life it will be worth it,” Aaron says of his charity work in memory of Luke.

He also encourages everyone to speak up about mental health issues, whether you’re experiencing them or concerned about someone who might be.

“The biggest thing you can do is break that barrier and admit you’ve got an issue and start talking. Papyrus have got their Hopeline, or talk to Samaritans. Some people hold it in, especially men, until it’s gone too far. I think that’s what happened with Luke, he held it in so long [out of] pride. Talking is definitely the best way,” he says.

“When you’re talking to someone and ask how they are, they say: ‘I’m okay’ - even if they’re having a bad day.” Aaron's advice? “Ask again. Say, ‘Are you actually okay?’” Who knows - it might just be exactly what the person needs.

Advice to remember

Suicide is preventable and there are places you can turn to for support. Indra Herbert, who heads up suicide prevention training at Papyrus, shares his professional advice for those who are concerned about someone they know.

Generally speaking, signs that someone could be thinking of suicide can be categorised in three areas; an historic and or recent adverse experience of an event, a change in normal actions or behaviours and the use of words or language that suggest they are struggling or having difficulties.

If you feel that suicide could be being considered, then talk to the person, share your concerns and reflect on what you see or hear. If still concerned, ask them clearly and directly if they are thinking about suicide and encourage them to seek professional support.

If you are concerned that suicide is being considered don’t ignore what you see, hear or feel. Don’t avoid engaging that person in conversation about your concerns. Don’t label someone as “not the type” or assume they will not act on the thoughts. Do take every sign seriously.

Being bereaved by suicide can bring deep feelings of confusion and anguish to the grieving process. Many people do show signs that they are contemplating suicide, but not everybody. Many people do seek support to stay alive, but not everybody. Many people can be prevented from acting on thoughts of suicide, but not everybody.

For practical, confidential suicide prevention help and advice for yourself or anyone else, please contact PAPYRUS HOPELINEUK on 0800 068 4141, text 07860 039967 or email pat@papyrus-uk.org.

Cosmopolitan UK's current issue is out now and you can SUBSCRIBE HERE. Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox.

Follow Megan on Twitter

You Might Also Like