Inside Truman Capote’s Legendary Black and White Ball: Worst Dressed Lists, Old Money Families and How the ‘Party of the Century’ Came Together

On the drizzly night of Nov. 28, 1966, writer Truman Capote would host “the party of the century” at New York’s Plaza Hotel. The Black and White Ball signified the peak of Capote’s career following the release of his bestselling true crime novel, “In Cold Blood.”

“I feel like I fell into a whole mess of piranha fish,” Capote told WWD weeks before the event, referring to the circling socialites, politicos and fellow creatives who were desperately angling for coveted invites.

More from WWD

What Capote called his “little masked ball for all of his friends” was anything but minuscule. Its 500-plus guest list was chock full of film, literary and high society icons. The party marked Capote’s successful foray into the starry world he’d always longed to be apart of.

Today, the Black and White Ball is considered a historical touchpoint of New York society. Many have attempted to replicate it, with the cast of FX’s “Feud: Capote vs. The Swans” attending their very own version of the storied soirée in celebration of the show’s premiere on Wednesday.

Ahead, WWD charts the legend and legacy of Capote’s Black and White Ball.

Who hosted the Black and White Ball?

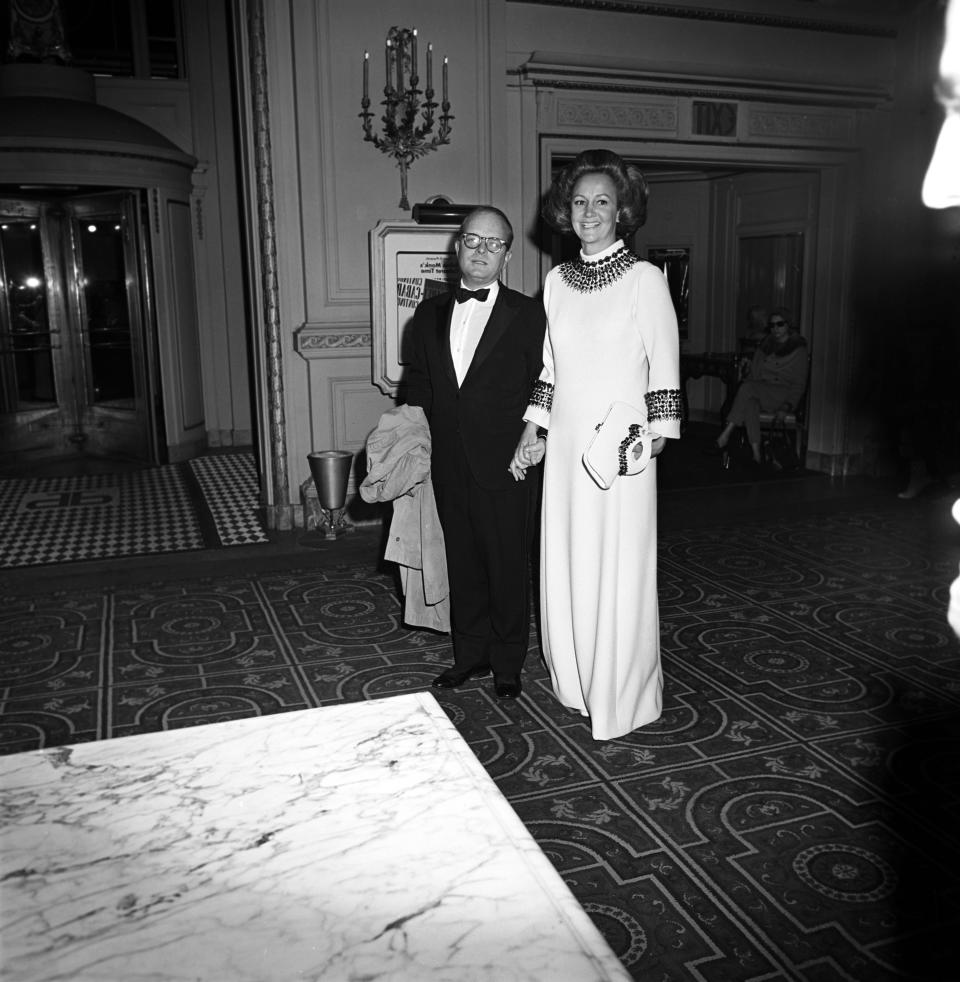

Capote threw the party in honor of Washington Post owner Katharine “Kay” Graham. Three years earlier, her husband and the paper’s former owner, Phil Graham, died by suicide, leaving Kay at its helm.

“Truman called me up that summer and said, ‘I think you need cheering up. And I’m going to give you a ball,’” Graham said in a 1991 Esquire article.

Inspired by the color palette of the iconic Ascot scene in “My Fair Lady,” Capote decided upon the black and white theme. It was then that Graham became the writer’s very own Eliza Doolittle.

“I really was a sort of middle-aged debutante — even a Cinderella, as far as that kind of life was concerned….[Capote] felt he needed a reason for the party, a guest of honor, and I was from a different world, and not in competition with his more glamorous friends,” Graham later wrote in her 1997 memoir, “Personal History.”

Among those glamorous friends Lee Radziwill, C.Z. Guest and Babe Paley — the latter having introduced Capote to Graham — were the coveted “swans” he would come to throw under the bus in his 1975 Esquire excerpt “La Côte Basque, 1965.”

In the act of thrusting Graham into society’s spotlight, Capote forever changed her reputation. According to his biographer, Gerald Clarke, “[Graham] was arguably the most powerful woman in the country, but still largely unknown outside Washington. [The Black and White Ball] would symbolize her emergence from her dead husband’s shadow; she would become her own woman before the entire world.”

Graham attended her coming-out party in a wool crepe Balmain gown trimmed in jet beads, with a mask custom-stoned by a then little-known designer named Halston. She went on to run the Post for two of its most noteworthy decades, raising the paper’s profile with its breaking of the Watergate scandal.

What was the Black and White Ball dress code?

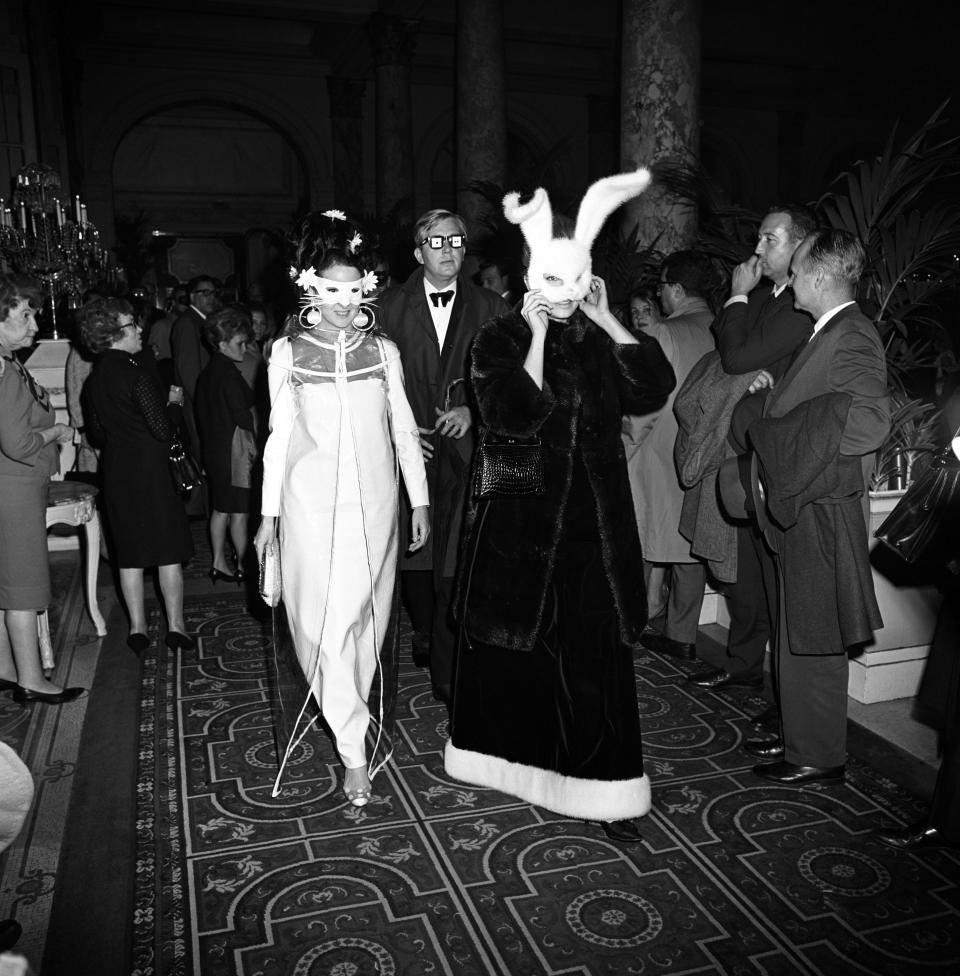

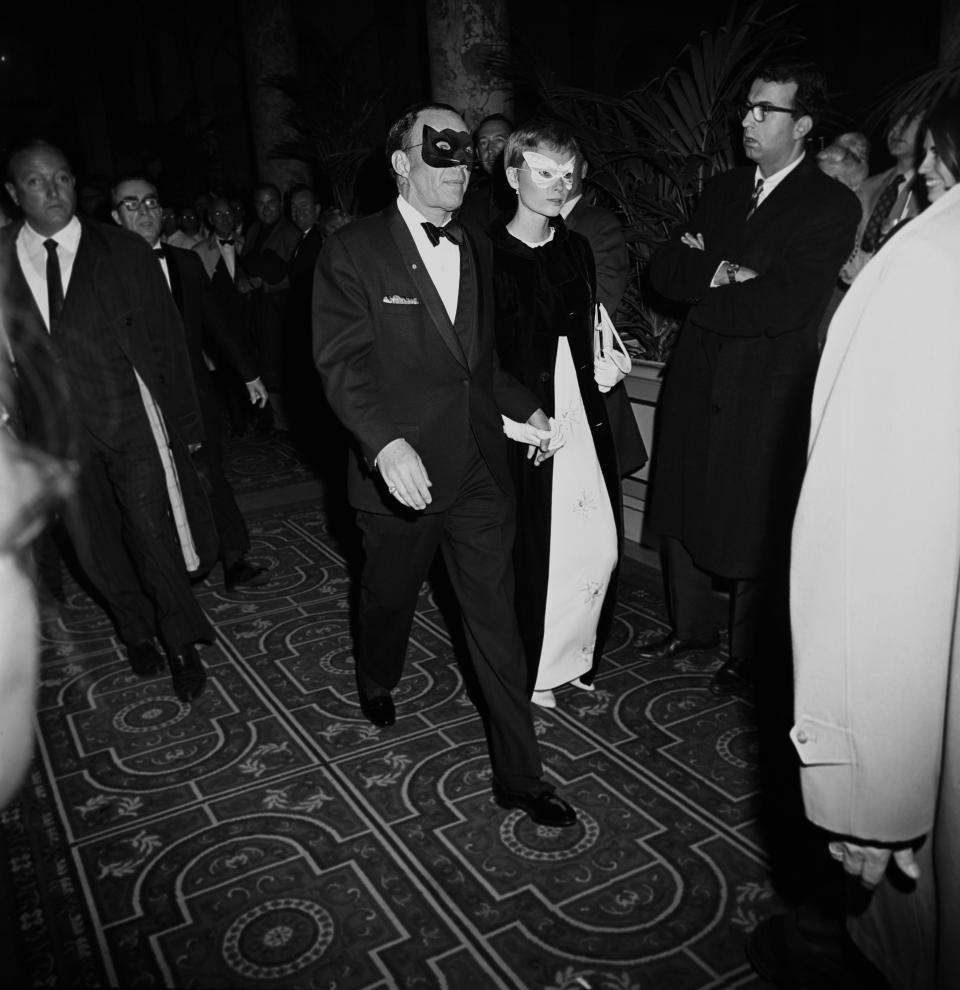

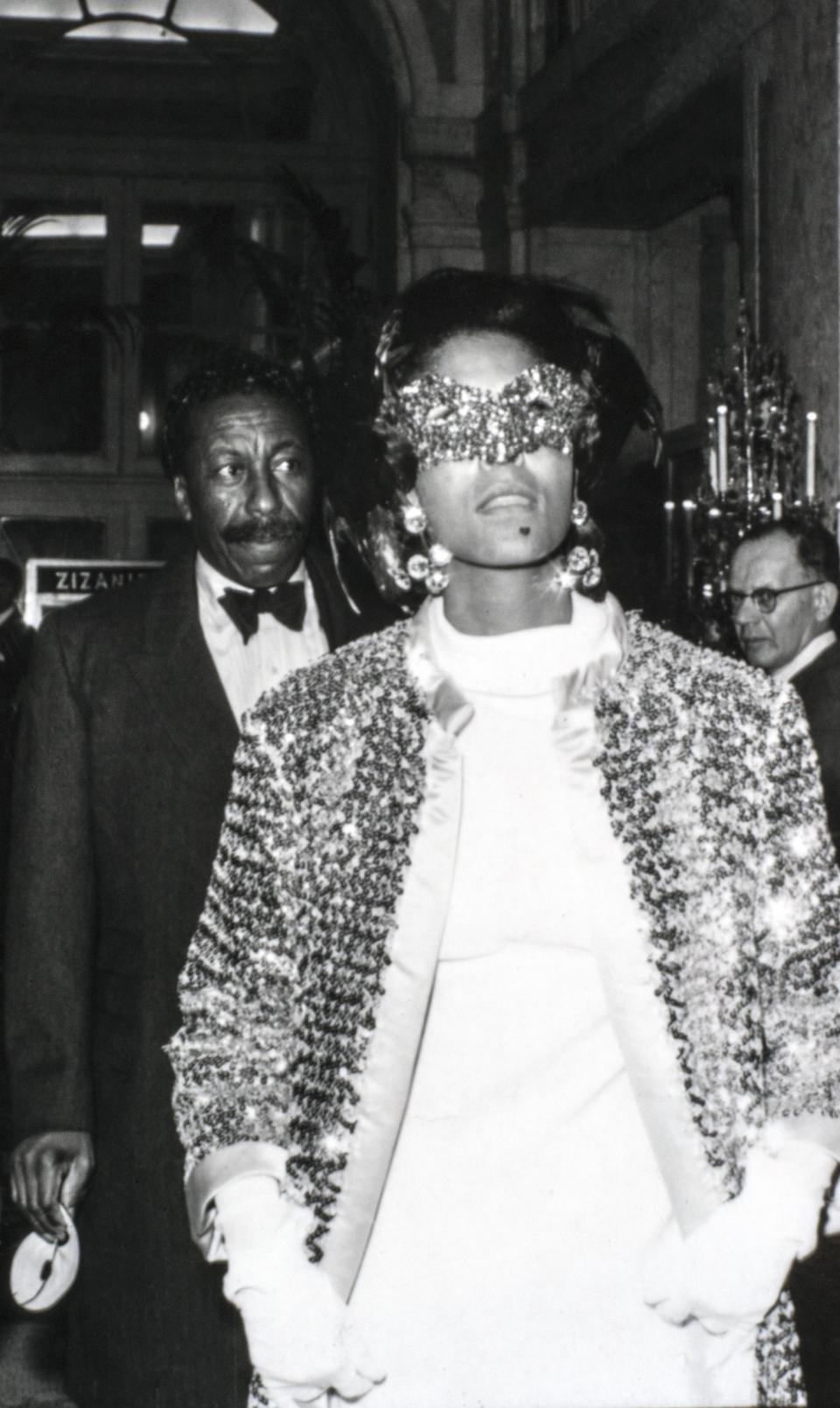

Aside from the obvious black and white attire, guests at Capote’s bash were also required to wear masks, which they were instructed to remove at midnight.

Halston, then a milliner at Bergdorf Goodman, devised dominos for numerous attendees, including Paley and actress Candice Bergen, for whom he trimmed a long-earred rabbit mask in $250 worth of white mink. “The ladies have killed me,” he told the New York Times.

Meanwhile, Cuban couturier Adolfo created 125 custom masks at his East 56th Street salon, selling nearly 100 more through Saks Fifth Avenue. “A lot of birds donated their feathers to the cause,” the designer explained in a 1996 Vanity Fair article. “For three weeks it was a real deluge, one lady after the other. I had to turn some away! My staff was up all night! I made them not just for the ladies — Merle Oberon, Adele Astaire, C.Z. Guest, Kay Meehan — but for some of the gentlemen too.”

While many spent as much as $600 on their masks, Capote purchased his for 39 cents at FAO Schwarz.

Where was the Black and White Ball?

Capote had become a millionaire off of his bestseller, so he spared no expense in renting out The Plaza’s Grand Ballroom. The writer spent $16,000 — the equivalent of more than $120,000 in today’s dollars — on his legendary shindig, though the decor was rather simplistic.

Tables were lined with red cloths and white tapers stood in golden candelabras wrapped with smilax. “The people are the flowers,” the ball’s interior designer, Evie Backer, wife of former New York Post editor George Backer, told the New York Times in 1966.

The ball’s midnight supper menu consisted of humble chicken hash, spaghetti bolognese, pastries and coffee. Nearly 500 bottles of vintage Taittinger Champagne were popped.

Who went to the Black and White Ball?

Capote spent months curating his guest list, which he kept tucked away in a cheap — and aptly, black and white — composition book.

“I think Truman was more excited by the preliminaries of it, by who he’d invite, and who he definitely would not invite,” Radziwill explained in Esquire.

Capote shunned critics that had panned “In Cold Blood,” and he even brushed off fellow writer Dominick Dunne, who later claimed that Capote lifted his party’s theme from a black and white ball thrown by Dunne and his wife in 1964.

“It was devastating if you weren’t invited,” Deborah Davis, author of “Party of the Century,” told The New York Post in 2016. “He totally angered some people. He’d say, ‘Honey, maybe I’ll invite you and maybe I won’t.’ Some people even offered money, and that never worked.”

As guests stepped out of their limos and into the lobby of The Plaza, they were greeted by a phalanx of nearly 200 photographers — more than had shown up when The Beatles stayed at the hotel in 1964. Outside, policemen on horseback corralled throngs of onlookers on Grand Army Plaza.

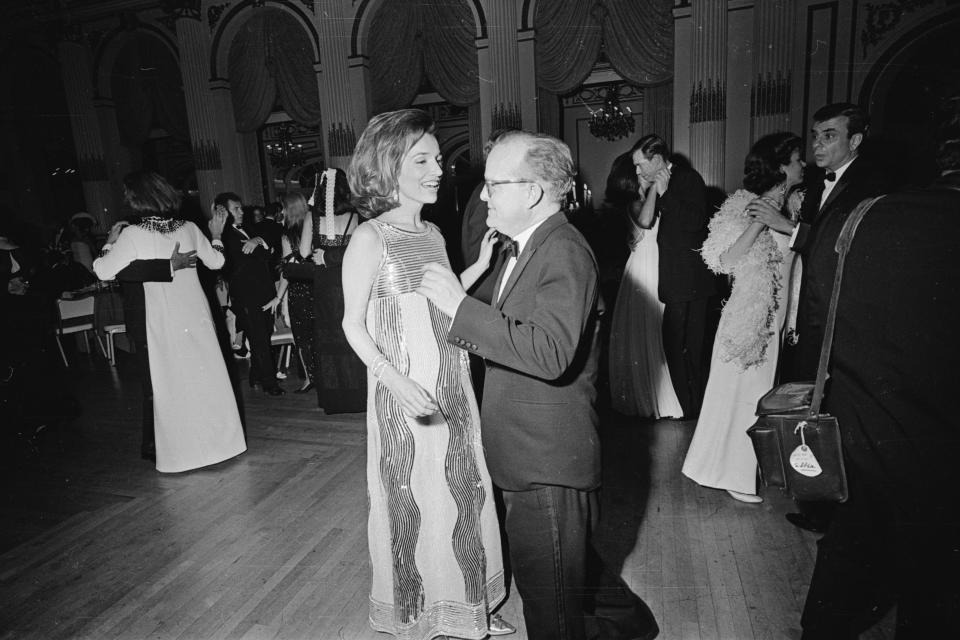

The ballroom’s media crowd was limited to just four journalists, including one from WWD. Four continents were represented among the evening’s 540 guests: artists, aristocrats, scientists, politicians, writers, tycoons and members of America’s most esteemed families (the Kennedys, the Vanderbilts and the Rockefellers) comingled for the first time.

Gloria Guinness and Jacob Javits hobnobbed with Henry Fonda; Lauren Bacall waltzed with Jerome Robbins; Norman Mailer and National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy nearly came to brawl over the burgeoning Vietnam War.

“I have always observed,” Capote explained to Esquire, “in almost every situation, that people tend to cling to their own types. The very rich people, for instance, tend to like the company of very rich people. The international social set likes international socialites. Writers’ writers, artists’ artists. I have thought for years that it would be interesting to bring these disparate people together and see what happens.”

Not all of Capote’s invitees were as renowned — the writer invited several characters from “In Cold Blood,” all of whom flew in from small-town Kansas. Alvin Dewey, the local detective who cracked the Clutter case and Mrs. Roland Tate, the widow of the judge who presided over the trial, were some of the last guests to leave the party around 4 a.m.

“It was marvelous because there was such a mixture of people, all kinds, all ages,” Kenneth Jay Lane told The New York Times in 2016. In the same article, Lane fondly recalled rubbing elbows with Old Hollywood starlet Tallulah Bankhead. “I talked to her for about three minutes, but then could say I’d met Tallulah Bankhead,” he said. “In the old days, it wasn’t a publicist society, and now it’s all publicists. People then had publicists to keep their names out of the papers, and nobody’d ever been to Kardashia.”

Impact and aftermath

The Black and White Ball generated a great deal of publicity in the days following the event. The New York Times printed its guest list, an honor normally reserved for White House state dinners. WWD rated attendees’ looks based on a system of stars, rewarding Gloria Guinness and art collector Marella Agnelli with the evening’s top scores. Mailer, meanwhile, was listed as worst dressed, earning a measly minus five stars.

The Black and White Ball was one of Capote’s final parties before his career and personal life took a downturn. Many of his high society swans eventually exiled him due to their salacious portrayal in “La Côte Basque, 1965,” and the writer became increasingly addicted to drugs and alcohol.

Today, the event’s legacy lives on: the season two premiere of “Feud: Capote vs. The Swans” borrowed its dress code and Plaza Hotel venue from the Black and White Ball. The legendary party will also be explored in an episode titled “Masquerade 1966.”

Looking Back at Truman Capote’s Black and White Ball: The ‘Party of the Century’ [PHOTOS]

Launch Gallery: Looking Back at Truman Capote's Black and White Ball: The 'Party of the Century' [PHOTOS]

Best of WWD