Eddie Jones Talks Mental Strength and the Pursuit of Perfection

Eddie Jones has less than a year to go before his eight-year contract as head coach of England’s rugby team comes to an end. Though if you believe the current frenzy, the relationship may finish sooner than that.

If he is to stay the distance, it will certainly be an eventful 12 months: the Six Nations kick off in February, followed by the World Cup next September. Jones has a few World Cup demons to slay, having twice taken teams to finals – his Australia losing to England in 2003, courtesy of Clive Woodward’s coaching and Jonny Wilkinson’s boot, then his England losing to South Africa in 2019. During our long chat at England’s Pennyhill Park base last month, he admitted it took him several years to get over that first defeat. Now 62, he says age and experience helped him deal better with the second one.

In between, the Tasmanian-born son of a mixed Australian-Japanese marriage, who himself married a Japanese woman, Hiroko, coached Japan and helped revolutionise the game there. Once he has left England – he is adamant he will, whatever happens – he is on the lookout for another ‘meaningful, transformative’ role. There is also a big sparkle in his eyes when I suggest he should try his hand at coaching in the sport he played as a child, rugby league. I would love to see that, what with rugby league – personal opinion alert – being the superior code!

His parents’ mixed marriage is an important theme in his life, and in this interview. It means he has never felt fully at home or fully accepted – perhaps useful for a working-class Aussie navigating the upper-middle class workings of a very English Rugby Football Union [RFU]. It also means too that he has developed a thick skin and it’s refreshing to talk to a high-profile figure who seems genuinely not to care what is said or written about him. In fact, he often only learns about the worst things from his 97-year-old mother in Sydney – one of a tiny handful of people on the planet whose views matter to him.

AC: So, whether we are talking playing or coaching, what is the balance between the physical and the mental?

EJ: I have never separated the two. I grew up in Australia, healthy lifestyle, always exercising, and I have kept that going. There is a reasonable pressure in this job, so I take breaks at the end of tournaments to recover, which always involves hard physical training. Before Covid, my wife and I would go to this CrossFit camp in Okinawa, a beautiful tropical island, train twice a day, relax, have a nice time, come back stronger.

AC: Is your mental health good?

EJ: I think so. I don’t sleep a lot, but I don’t have sleep problems.

AC: How much sleep a night?

EJ: Maybe five hours. I take a half-hour nap in the day, if I can. I don’t feel that I have stressful periods. I can get bored. That is the only time I get stressed.

AC: You never feel a stress that is almost physical?

EJ: No. I was lucky in that my parents brought me up to be quite balanced in how I saw things. They had an unusual marriage, [Australian father, Japanese-American mother] and my mother was very forgiving, even though people could be very rude to her.

AC: She faced a lot of racism?

EJ: Yes, but she never carried the hurt. I’m similar. If someone is having a go, or there is stuff raging in the media, it never worries me.

AC: Is there a danger that makes you less understanding of how other people might get affected by things that you say?

EJ: I’ve never thought of that. I have become more cognisant of other people’s worries. When I was younger, I was less tolerant. I just wanted people to be like me. Now I think about their feelings.

AC: What do you mean by ‘be like me’?

EJ: ‘Get it done. Don’t worry. Get on with it. No excuses.’ The players I coach now, there is a lot more going on in their lives. Their whole life is rugby, so if something happens in rugby it can affect everything. When I was growing up, sport was a part of your life, not all of your life. I can ask guys today, ‘When did you decide to be a professional rugby player?’ And they might say as early as 12. Well, if you get disappointment or injury, your whole life is affected. It’s one of the reasons mental health is such an issue for sportspeople now.

AC: In your playing days, would a coach have thought about the mental health of a player?

EJ: No. If you weren’t up for it, you were ‘soft, don’t need him’. Now, we are more aware of the anxiety players can suffer due to poor performance or criticism and media pressure, and we try to support them.

AC: I get the sense you really don’t care much what the media say about you. It doesn’t get to you.

EJ: That’s right, mate.

AC: Would players be stronger and better if they had that attitude? Do you try to help them get it?

EJ: They would definitely be better. The most influential person in your life is you, and that’s the only person you should be listening to.

AC: But hold on, you’re the coach! You want the players to listen to you.

EJ: I want them to coach themselves. I am a guide. The best players have always been their own best coaches. You might have someone who carries your bags, or helps you in a particular area, but the players all drive their own careers.

AC: So what is your job?

EJ: I am a facilitator. We play a very difficult game: 15 players on the field together, all interdependent. We have to facilitate an environment in which they understand that being their own best is not always the best for the team. They may need to modify to help the team as a whole. That is why rugby is such an intriguing game. In cricket, if you’re Ben Stokes or James Anderson, you run in and you bowl fast. In rugby, you’re always cognisant of the interdependence of the whole team.

AC: Do you think the fans get that?

EJ: No, they don’t. That’s the hardest thing, understanding it is such a team game, all the time.

AC: When you get a lot of flak, is there ever a point where you think you should stop and listen, or do you always push it to one side?

EJ: I push it to one side. You have to be in the game to understand this because coaching changes so much. I was talking to a kid in the bar earlier, a Chelsea supporter. He was saying the manager was under pressure. Just 12 months ago, he was the best thing that ever happened to Chelsea. I was with a cricket coach yesterday. He won the IPL. But then he started coaching in The Hundred and didn’t win a game. So he’s thinking, ‘Am I the best or the worst?’ There are extremes, and you have to keep a moderated view. Life is a continuum with best to worst at the extremes, and you’ve just got to keep bubbling on.

AC: And not take it personally.

EJ: Correct.

AC: So if Clive Woodward has a pop at you…

EJ: I feel sad for him. If that is the best thing he has to do in his life, then he hasn’t a lot to do.

AC: Would you ever do that, take a pop at your successors?

EJ: No, I’m going to make sure that I don’t. There’s another way. You don’t need to do it. Rod Macqueen, Steve Hansen, great coaches. They just get on with the rest of their lives. When you’ve had your turn, you give it to someone else.

AC: Are you definitely going to go next year?

EJ: Yes. I only came for four years. Then we lost the World Cup final in 2019 – I felt I could still contribute, so did the RFU, so we agreed another four years. I knew it would be difficult because we would have to change the team. I’ve enjoyed it, it’s a great position, but eight years with the same country, that’s enough.

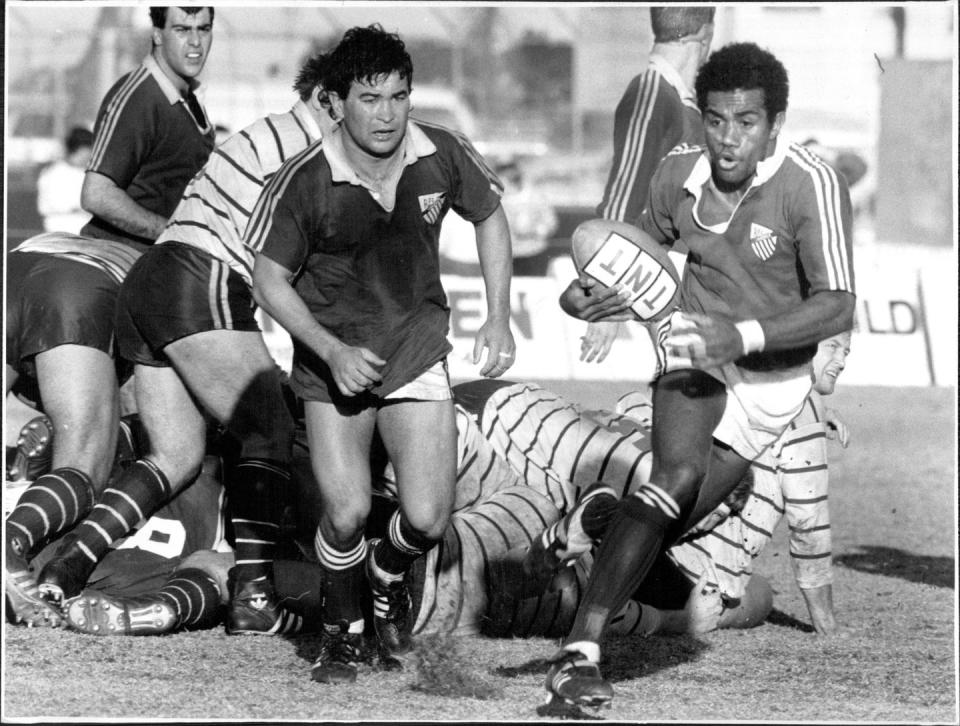

AC: You’re a working-class guy. Why rugby union and not rugby league?

EJ: It would’ve been rugby league – I grew up playing league, I loved it. But then I went to high school and turned to union. It was a little school. The Ella brothers [Mark, Glen and Gary] went there and they revolutionised rugby. There was one day we played St Joseph’s, the big private school in Sydney, and we beat them. Just a normal school. It produced a revolution. There have been three Australia coaches from that one school, all working class, so that’s quite an effect. We changed rugby.

AC: Have you never fancied coaching in rugby league?

EJ: I would, but no one has offered me a job [laughs].

AC: Why not?

EJ: It’s a different sport, lots of nuances. You would need to spend a lot of time on it. I’ve been asked to talk about jobs before, but it’s never been the right time.

AC: You could do it.

EJ: I reckon I could.

AC: You’ve got to do it. What do you like about rugby league?

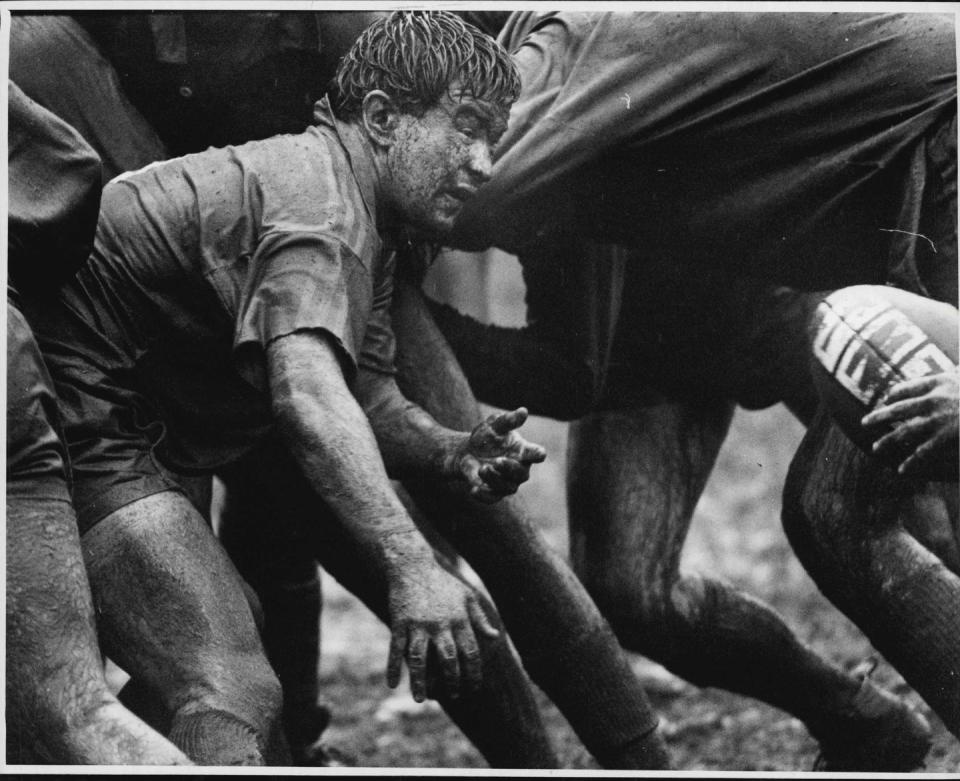

EJ: The simplicity of it. The intensity, the speed, the skill, the courage.

AC: Is there the same league-union class division in Australia as in England?

EJ: It’s not exactly the same but it’s there. There are certain countries where it’s more mixed I think – South Africa, New Zealand, France – whereas the Anglo-Saxon countries tend to have the class thing.

AC: With the RFU, do you not feel a bit fish-out-of-water?

EJ: Not really. I enjoy it.

AC: Do you enjoy being seen as different?

EJ: I don’t seek out to be different.

AC: But you can’t always just be in your own little world where you don’t care about what people think.

EJ: I’ve maybe never really felt at home anywhere.

AC: Because of being mixed race?

EJ: Yeah, mixed race. Growing up in Australia, half-Japanese, but then that’s not the same as being Japanese. When I went to work in Japan, my wife – who is 100% Japanese – gave me the best advice. She said, ‘Don’t ever think they will treat you as Japanese.’ And they don’t. So coming to do the job for England, one of the reasons I wanted to do it was because it would be so different. And I’ve enjoyed it.

AC: So you’ve done the job for three countries. What have been the differences and the different challenges?

EJ: Generally speaking, Australians are brasher. The English are more passive but strong-willed. If you get in the right stream on that strong will, you get a great result. The Japanese basically want to be led but that is changing. Nowadays, the players there want more of a say, too.

AC: Are there any challenges unique to England?

EJ: Probably the hardest thing here is that we get so little time with the players. The players are owned by the clubs, and there’s this complex relationship between the clubs and the RFU, with the players somewhere in between. Trying to understand those relationships is difficult.

AC: Have you decided what you’ll do next? Is this your last big job in Union?

EJ: I’m 62 now and I think in pure coaching terms I am coaching better than I ever have. Results aren’t always perfect, but I’m happy with how I have been coaching. After this, I want to do something really meaningful. I’ve enjoyed England a lot, it was a bit of a rescue job at the start, now rebuilding, and I am confident I will leave things in good shape. Japan was a free hit, a country that had never known winning and we changed that. So next, maybe take a smaller country, or a country where the game needs to be repaired.

AC: Would you fancy Scotland?

EJ: I wouldn’t coach against England in the domestic tournaments.

AC: Once you’ve left this job, if Australia play England, who would you want to win?

EJ: Don’t care really. On international allegiance, I am Australian and I want Australia to do well, but I also want Japan to do well, and in the end you love the players, so it depends on the players I know. If guys like Maro [Itoje] and Owen [Farrell] are playing, I’d support them.

AC: So why this reputation for being a hard man?

EJ: I’ve been hard at times, no doubt.

AC: Your definition of ‘hard’ being…

EJ: Probably being relentless in the pursuit of improvement and not doing it in the best way. What was seen as hard 20 years ago is not acceptable now. You can’t talk to the players in the same way.

AC: Is that good or bad?

EJ: It’s just the way it is. You can still guide a player, give the same message, but not in the same way.

AC: But are there not players who would benefit from you pinning them up against a wall and saying, ‘For fuck’s sake, sort yourself out?’

EJ: There are some players you could talk to like that. But fewer. And you couldn’t pin them against the wall [smiles].

AC: You got into a bit of bother for seeming to criticise the hold of private schools on the game, saying it made for overly cosseted players. Why were you rebuked for telling the truth?

EJ: I don’t know what was written because I never read it. But the whole thing has been: how can we get better diversity? If that was taken out of context, I don’t know and I don’t care. But I’m really proud of what we have done here, and of players such as Ellis Genge and Kyle Sinckler, who have come from non-traditional rugby backgrounds and just been terrific for us.

AC: But you do feel if you could broaden the talent pool, England would be more competitive?

EJ: One hundred per cent. It’s a challenge. Australia has the same thing. When I coached the Queensland Reds, the whole side came from eight private schools. Now you have kids who come from country areas breaking through. It’s becoming more common. That will happen here, too.

AC: How do you see England’s prospects ahead of the World Cup next year?

EJ: If this was the Cheltenham Gold Cup, there’s a pack of four out front – France, Ireland, South Africa, New Zealand – and we are fifth, right behind them, right on the rails. A good position, provided we keep improving. Australia are there or thereabouts with us. It’s going to be the closest World Cup ever. France and Ireland are the in-form teams right now, but things will change.

AC: How big a disappointment was the last one, losing the final in 2019?

EJ: It was bad.

AC: How long does it take you to get over something like that?

EJ: I was able to be more balanced that time. We did okay, but we were just not quite good enough. I was terrible after losing the final in 2003. It took me three or four years to get back to where I was. I was so desperate to win that. I didn’t coach well.

AC: What does that mean when you say you didn’t coach well?

EJ: It was more about my desire to win something than developing the team. It was broadly the same team that had won the previous World Cup, and it had only ever been done once before, winning two in a row. So by getting to the final, you’ve done well – there are 18 other teams who didn’t get there. But then you lose and you’re seen as a failure, and then you have to rebuild the team. Players lose motivation, some players get swayed by money, others get old.

AC: But three or four years? That is a long time! Do you get down, get depressed at times like that?

EJ: Frustrated. I get frustrated.

AC: Do you relive it, relive what went wrong?

EJ: No, it’s just frustration. And then you start to think maybe you’re not the problem, the players are. But that’s not the way to think. You always have to be thinking, ‘How can I light them up?’ If I’m not lighting them up, I’m doing something wrong.

AC: So if anyone mentions that Jonny Wilkinson drop goal that won England the final in 2003, is that like a dagger through the heart, even now?

EJ: Well, people do mention it a lot [smiles]. And as you say that, I can certainly see it flicker through my head. I mean, that tournament was a great time to be an Aussie. I’m coaching the national side on home soil in a World Cup. The Prime Minister, John Howard, was hosting a reception for us and one of the players said to me, ‘I wish this could go on forever.’ So then losing, that really, really hurt. In 2019, I got over it much quicker. I was older, more experienced. When you’re young, you don’t always learn the lessons you should.

AC: ‘I love winning’ or ‘I hate losing’ – which of those two statements most applies to you?

EJ: I love winning.

AC: I think that puts you in a minority of the coaches and athletes I’ve asked. What do you most love about winning?

EJ: Getting 15 guys to play together with a superiority, everyone understanding each other, everything in unity and motion… when it clicks, it’s like a symphony.

AC: Still, I bet if you had won that World Cup in 2003, or 2019, the buzz wouldn’t have stayed with you for three or four years, would it? So, defeat hurts more than victory gives joy, no?

EJ: You know the story of the Seattle Seahawks, when they win the Super Bowl and they’re all there with their hands on the trophy? The coach, Pete Carroll, he says, ‘We have done what we set out to do.’ And then there’s a pause, and they all think he is going to say, ‘We won the trophy.’ But he says, ‘We found our best.’ Playing at the highest level, you are always trying to find your best.

AC: Have you ever had a game where all 15 were at their best?

EJ: Been close to it, mate. The 2019 semi-final against New Zealand was almost a perfect game. We were so good that day. Japan against South Africa. There have been times it was close. But there has never been the perfect game.

AC: When we’re watching and we see you guys up there in the stands, fans always think they know what’s going on. But what is the gap between what you see and know, and what the fan sees and knows?

EJ: Big.

AC: It’s like Sean Dyche always says to me, ‘You think you know about football, but the truth is you know the same as I do about politics: next to fuck all.’

EJ: [Laughs] I can imagine him saying that.

AC: So what is the gap between you and the guy in the Barbour jacket?

EJ: The big gap is the back stories, what happens during the week, the relationships between the players, what happens in their private lives. There might be something going on at home, something bad might have happened at training. We have to know the players so well that we are getting them to be their best and making them feel they can trust the environment in which we want them to give their best.

AC: But from their perspective, is there not a risk that if they are open they might put stuff in your head that makes you doubt them? How do you get to honesty and trust?

EJ: Before the 2016 Australian tour, I made a speech to the team, setting out what it would take, how hard; I said it would be a Herculean effort. And Joe Marler came to me at the end and he said, ‘I can’t give you that, I can’t go.’ He had some issues and he is a very honest guy. But it takes a mature person to do that, to say he can’t give his best. Other players, you see it in their eyes.

AC: What are your three top sports outside rugby union?

EJ: Cricket, rugby league and horse racing.

AC: Are you a betting man?

EJ: Used to be. Not for a long time.

AC: Not football?

EJ: I do love it but it’s not my natural sport. I don’t know enough. I enjoy the drama it brings.

AC: Can you get anything out of watching the top football coaches?

EJ: The superficial stuff, maybe. I look at Pep Guardiola and Jürgen Klopp and they strike me as being good at managing young players. They are always very positive; even if the message is tough, they do it in a positive way. So I can get things from the pre-match and the post-match stuff, but not how they do the job. You would need to spend a lot of time to go deeper.

AC: Which do you prefer between coaching club and country?

EJ: No comparison, mate. Internationals. You’re coaching the best players, they’re playing in front of huge crowds, the buzz you get is great and it means so much to people. After the successful tour in Australia, everyone is coming up to you, wants to pat you on the back. Have a bad game and they’re looking the other way, like you’ve been done for murder [laughs]. But you can change a lot through sport. In Japan, we changed the way the game was played and the way it was seen, and that changed the country. Look at the England women’s football team and what they have done, the girls they will have inspired to say to their mum or their dad, ‘I want to get into football.’

AC: Are you good with players in defeat? How do you deal with the ones who fucked up?

EJ: I’m pretty good. You have to create optimism straight away. Identify problems, find solutions. With players who haven’t done well, you need to get on the front foot, make them realise they’re not suddenly bad players, get the others to support them. Because on another day they might win it for us.

AC: What have been the biggest changes since your days as a player?

EJ: The greatest change would be that the players talk less about the game because their lives are so much more full. We are trying to construct an environment where they talk more. A lot of players today are more students of their own careers than the game.

AC: So paradoxically, professionalism has made them less obsessed with the actual game than you were in the amateur era?

EJ: Yes. I want them back to being the six-year-old kicking the ball in the park and loving it. The variation between loving it and not loving it is large.

AC: If you love it, are you a better player?

EJ: Yes, that follows.

AC: And your career lasts longer?

EJ: Yes.

AC: Has money changed the players?

EJ: Not a great deal.

AC: Social media?

EJ: You’ve got to realise how influential it can be for the players. You don’t realise how much abuse they get if they’ve had a bad game, and unless they are sharing people, you won’t know what it is doing to them. So if you see them kicking stones on Monday morning, you have to talk to them about it.

AC: Would you ask them why they were worrying about what some twat who never played the game is saying?

EJ: I remember watching a documentary on Australian swimming. There was a young guy, he said, ‘500 people might write how good I was; one says I am bad and I spend all night thinking about that one.’ That’s why I don’t read it. It gets in your head and it’s hard to get it out of there.

AC: Could you persuade that swimmer to change that mindset?

EJ: Hard, if that’s the way it is.

AC: So you’re lucky to have thick skin.

EJ: Age helps. When I was younger, I definitely read the papers and could be affected by it. My mother is 97 and she reads everything. She lives in Sydney and I try to call her every morning. She’ll say, ‘Is this true what they’re saying? I told you not to swear!’ [Laughs] I’m very lucky with my wife. She doesn’t read anything about me.

AC: So you’ve got yourself, your mum, your wife – is there anyone else whose opinion matters to you?

EJ: I’ve got a guy called Neil Craig, an Aussie rules coach, coached for a long time, a bit older than me. He is our high-performance director, but basically a second set of eyes for me.

AC: A mentor?

EJ: Yes. Every morning we have a coffee and just go over what we need.

AC: You must have dropped hundreds, maybe thousands of players in your career. How easy do you find that to do?

EJ: It’s always the worst part of the week. You’ve been telling guys you love them and then you tell them you don’t. I’ve learned that it’s all about the tone. The truth is as soon as you tell them they’re dropped, they’re not listening – all they remember is how you did it. They are always going to be hurt, but as long as you show you care and show hope, usually they are fine.

AC: What about if you are moving them out for good?

EJ: That’s even harder. We dropped the Vunipola brothers, but we keep contact. There is always a chance you might need them, you keep the bridge open.

AC: It’s about human relations, then?

EJ: Yep.

AC: What do you see as your best qualities?

EJ: I always strive to be better. And I see the game pretty well.

AC: Did being a teacher help you be a coach?

EJ: It is the foundation of all coaching. Coaching is teaching.

You Might Also Like