All the Worst Humans by Phil Elwood review – confessions of a cleanup man

‘Operators like me oil the machines that prop up authoritarian power all over the world,” writes the Washington PR man Phil Elwood in All the Worst Humans. “I help those machines function by laundering the sins of dictators through the press.” He may be overselling himself – he’s a publicist, after all – but not by much, if we are to believe his romping memoir of a career spent manipulating the media on behalf of the bad guys.

It’s no shock that the obscenely wealthy pay large amounts of money to PR companies to “change the narrative” in their favour. What’s more surprising is who these companies will work for, and what they are prepared to do. No job, it seems, is too big or too dirty. In 2018, the Washington firm Qorvis took $18.8m from the Saudis in what Elwood calls “PR cleanup fees” after the Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi was murdered and dismembered in the Saudi Arabian consulate in Istanbul. Up to the Sochi Olympics, New York agency Ketchum counted Vladimir Putin as one of its biggest clients, and took a reported $40m off the Kremlin and Gazprom. But the company whose machinations Elwood exposes in most detail is one he worked for, Brown Lloyd James, a boutique “strategic consultancy” founded by Peter Brown, who once managed the Beatles. It was at BLJ that Elwood performed many of his lowest tricks.

Brown, who, we are told, lives by the maxim “anything is possible with the right amount of money”, is close to rock royalty. He was name-checked by John Lennon in The Ballad of John and Yoko, and attended Paul and Linda McCartney’s wedding as a witness. His Rolodex contains some of the most famous names on the planet: guests at his parties have included Donald Trump, Barbara Walters and Yoko Ono. He’s also unafraid of deploying his contacts in the service of what Elwood describes as a host of “foreign baddies”.

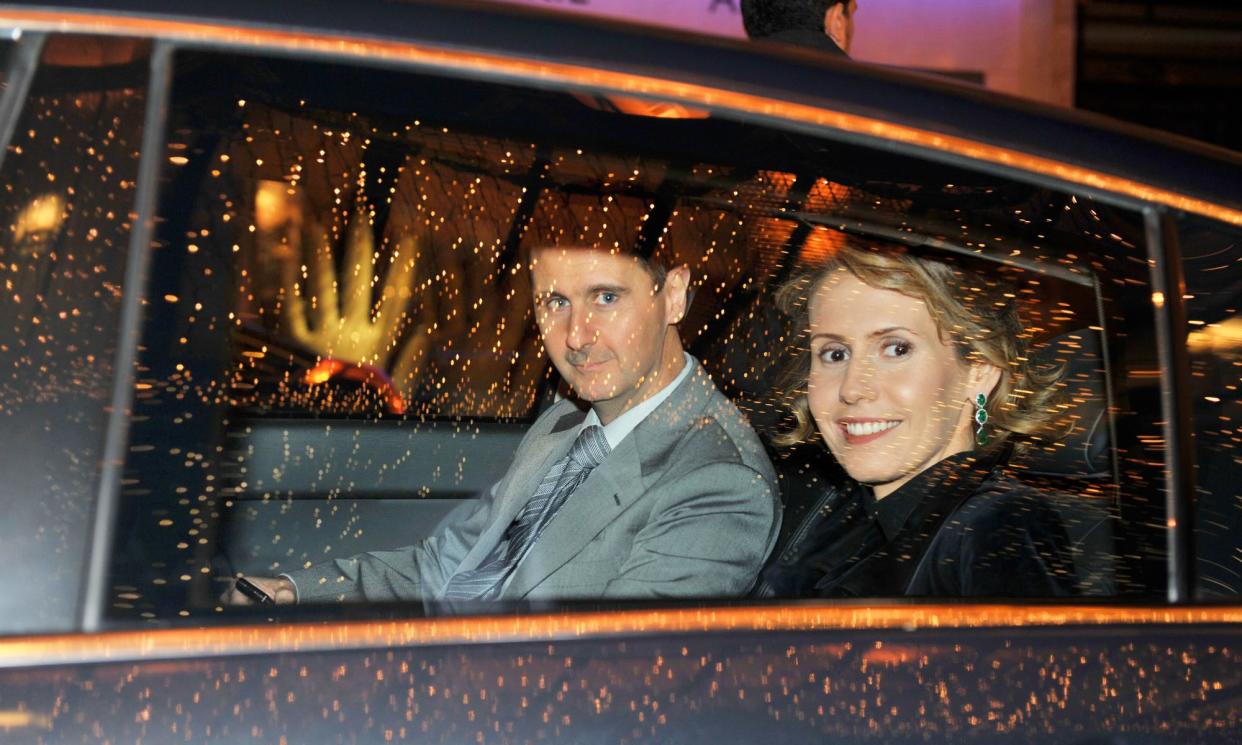

One of Elwood’s early BLJ jobs, he writes, is to accompany Mutassim Gaddafi, a son of the Libyan dictator, on a drug- and alcohol-fuelled bender through Las Vegas, to try to keep him out of the papers. The PR man runs around the Bellagio Hotel, sourcing vintage champagne, private jets and more for Mutassim’s entourage, terrified that the intoxicated, armed Libyans will shoot him if anything goes wrong. Other unscrupulous or tyrannical BLJ clients included Ali Bongo, the leader of Gabon, and Bashar al-Assad, the Syrian president. It was Brown himself who set up a now infamous US Vogue interview with Bashar’s wife Asma by picking up the phone to his old friend Anna Wintour, Elwood writes. The article that subsequently appeared, headlined A Rose in the Desert, gushed that Asma was “glamorous, young, and very chic – the freshest and most magnetic of first ladies”, and described the tyrant’s family as “wildly democratic”. BLJ couldn’t believe their luck: “It’s rare you send a journalist on a propaganda tour and they actually print the propaganda,” Elwood writes.

Whitewashing a murderous regime isn’t illegal, but other BLJ campaigns came closer to that mark, according to Elwood, such as the one he ran to torpedo the US bid to host the 2022 World Cup. Hired by Qatar, BLJ planned to undermine the American pitch, which was fronted by Bill Clinton, by raising the spectre of political resistance at home. Using a regular PR “black ops” tactic, Elwood found an “astroturf” nonprofit to lobby against the US bid on the grounds that the money should instead be spent addressing childhood obesity, a favoured issue of Michelle Obama. The Healthy Kids Coalition, as the nonprofit was called, looked like a parental campaign group, but in fact was just a shell, which masked the hand of LBJ’s client, the Qatari royal family. To make his fake campaign more credible, Elwood drew up a supportive congressional resolution, and paid $10,000 to get a lame duck legislator to propose it – “You can get them to do anything,” he writes. He then leaked it all to a tame journalist, even inveigling Obama’s name into the copy, although she knew nothing about it.

Once the story was published, Elwood’s fake campaign had “ink”, which meant it had life in the real world, and when Fifa met 48 hours later in Zurich to pick the winning bid, the Qatari delegation could present the news coverage as evidence that the tournament was controversial in the US. Result: Qatar won the right to host the 2022 World Cup in what is widely regarded as the most corrupt vote in Fifa history. Despite the controversy surrounding it, the tournament would prove a triumph for the Qataris, since, as Elwood says, “sportwashing works”.

Elwood is vindictive about his profession. He is particularly scathing about the way big players who have proved themselves working with American corporations in DC and New York export their skills and strategies to the highest foreign bidder. The worse a regime’s mess becomes, it seems, the more money there is to be made. “I consider every crisis a golden opportunity,” he writes. “If my client lights their house on fire, you can be damn sure I’ll get the press to blame outdated fire codes.” He calls the PR industry a “parasite” that “lives off its host, the media”.

Elwood is an egotist, a bragger who has screwed the world and is now looking for redemption

A more considered way of looking at it might be as the yin to journalism’s yang: these are the interconnected forces of public information. They feed off each other, and can counterbalance each other. The difficulty is that as the news media has declined, PR has ballooned. For every American journalist there are roughly eight PR professionals, according to Elwood, who are invariably paid far more than the reporters. It is no longer a fair fight. When the “narrative” is increasingly controlled by media manipulators serving the interests of their clients, truth gets twisted.

This is a tabloid confession of a book, an insider’s account of working in the reputation launderette, and an apology too: it is one of Elwood’s “deepest regrets”, he writes, that he helped Qatar win the World Cup. It’s a taut read, full of hyperbole. He is “one of the most dangerous people in the business”, he tells us, who has manipulated narratives – even invented them when needed – to fix problems for a client. “I’m not proud to say I’ve seen the destruction my handiwork has created,” he writes. “We live in dangerous times, and my industry helped make them so.”

Elwood is an egotist, that much is clear, a bragger who has screwed the world and now comes looking for redemption in the form of this exposé. But as the last chapters reveal, he’s also a little more complicated than that. Perhaps it’s just a mark of how good he is at spin, but by the end I came round to rather liking the guy.

• All the Worst Humans by Phil Elwood is published by Atlantic (£20). To support the Guardian and Observer, order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.