Why we all love a Christmas romcom

I fell in love last week. I’m talking euphorically, addictively, thinking about him all the time, going to bed and dreaming about him, head-over-heels besotted. His name is Max, and he’s an IT temp in his early twenties at a Stockholm publishing house. Max is loving, open-hearted, non-judgemental, and the emitter of passionately soul-searching gazes. He sees the woman of his desires – sees all of her – and loves her for what she ought to love about herself, yet represses in order to pass as socially acceptable. And the kissing: the kissing is sublime.

Am I being unfaithful to my partner of nine years? No, although I have started following Björn Mosten, the actor who plays Max in Netflix’s Swedish comedy drama, Love & Anarchy, on Instagram. Is there a degree of wish fulfilment in my obsession with this tale of a midlife woman being found fascinating? Sure. Coupledom may have brought me true love, but true love lacks the dragging compulsion of high romance. The only individuals who currently find me fascinating are my five-year-old niece and my dog, and the latter prefers my boyfriend.

I am clearly not the only viewer living for love as December grinds into gear. Netflix is rolling out its annual deluge of festive dross rom-coms (drom-coms?), with titles such as Yoh! Christmas. Critics are raving about the art-house romance, and Palme d’Or nominee, Aki Kaurismäki’s Fallen Leaves, in which the path to love is beset by lost phone numbers, mistaken addresses and a stray dog. Even Ridley Scott’s Napoleon sees the conqueror’s empire-building through the frame of his S&M devotion to Joséphine.

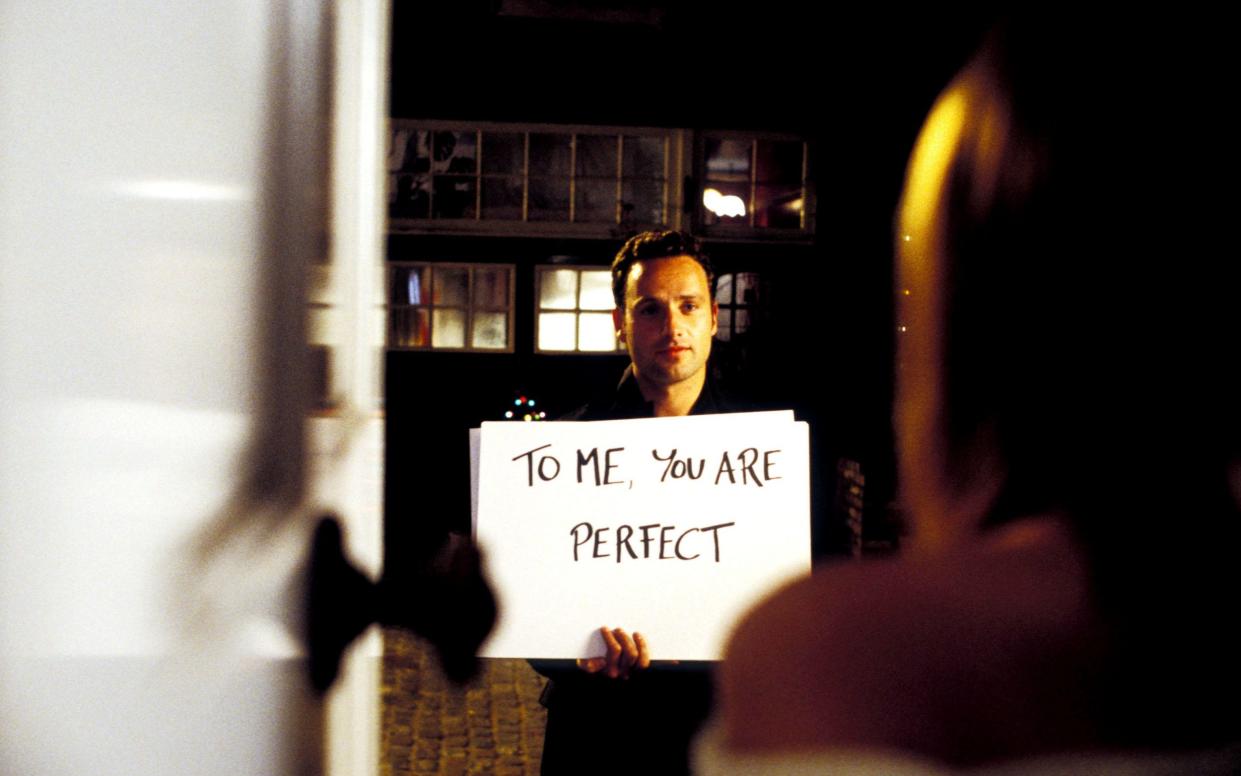

What is humankind’s psychological need for romance; not least in mid-winter, when the craving to wrap ourselves in this emotional comfort blanket is at its most intense? Loneliness may play its part, with more of us isolated in our lairs than in the summer months. Certainly, this was Netflix’s implication when it tweeted in mid-December 2017: “To the 53 people who’ve watched A Christmas Prince every day for the past 18 days: Who hurt you?” A move criticised for mocking the very souls the streamer service relies on. Besides, how many more views had there been for Nancy Meyers’s The Holiday, or Richard Curtis’s ghastly Love Actually?

When life feels achingly mundane, the opportunity to live vicariously through a more incidental narrative is strong. All story-telling has been found to involve what psychologists have referred to as “narrative transportation”: an engagement of the senses that causes changes in brain chemistry, such as the release of feel-good chemicals dopamine and endorphins, and the bonding buzz oxytocin. How much more so when said story involves love itself as its theme?

Most of us harbour a longing for epic and immortal love, even those of us who consider we may quietly have found it. When I was young, I lived for this form of high drama, in art as in life: love at first sight, passionate declarations, theatrical gestures. Alas, experience teaches us that these people are (unappealing) maniacs, “romance” an excuse for all manner of less attractive behaviours we now deem “controlling”, “stalking” and “gaslighting”. As a culture, we’ve become more attuned to calling this what it is – abuse – a putting of women on a pedestal in a way that also implies a pit, allowing them little by means of agency either way. There’s a reason why we refer to the “object” of the lover’s affections. Do I long to be in this position again? I do not.

In real life, “limerence”, the obsessive attachment to another person – worse, theirs to you – causes chaos. However, fiction provides a safe space in which to experiment with such highs and lows. While, over Yule, a time of year when all manner of extraneous emotions are hurtling about, it supplies a convenient means of catharsis, releasing repressed emotion in a great gale of sighs.

Still, there’s more to it than this. Fiction has always taught us how to love. This was as true for the urbane Augustan audience of Ovid’s Ars Amatoria of AD 2, as it was for the readers that lapped up Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur, one of the first books printed in England in 1485. Petrarch taught lovers to exist in antithetical shudders of burning and freezing; John Donne concocting a laddish fantasy world in which he could apostrophise: “For God’s sake hold your tongue, and let me love,” yet still avail himself of his mistress’s favours. We read and we learn how love is felt and expressed, reproducing its troped behaviours.

It no less shows us what is loveable about ourselves. The thing that moves me about Love & Anarchy is the notion that its heroine, Sofie, is most alluring to the heroic Max not in her successful executive guise, but when she is at her least conformist, most bolshily unbiddable, vaguely nutjob, a woman unleashed in all her aberrant selfdom.

Obviously, I enjoy the fact that this is presented in modishly Nordic packaging, all beanie hats and craft beer. Nevertheless, this is actually the message of all our most popular love stories, from Mark Darcy informing Bridget Jones, “I like you – very much – just as you are,” to, presumably, Thando, protagonist of Yoh! Christmas, taking 24 days to discover that she has to love herself before she can discover the man of her dreams. Or, as that cultural oracle, Ru Paul, puts it: “If you don’t love yourself, how in the hell you gonna love somebody else?”

These are our love stories because this is the way our society holds that we should live at our most functional, whether single or in a couple: honestly, openly, and as close to authentically as possible. In this context, my pash for young Max becomes a positive mental-health act. Oh, God, Max. It’s going to take me a while to get over him. And I’ll enjoy – and psychologically benefit from – every last moment.