Why Britain has never forgiven – or understood – the Teddy boys

The Teddy boys of the 1950s were an exotic breed. With their drape jackets, velvet collars, elaborate waistcoats and drainpipe trousers, they were the first recognisable working-class youth movement – an advance scouting-party at a time when society was only just learning to identify that strange new species, the teenager.

In a world which has since become accustomed to waves of once-controversial styles such as mods, hippies or punks, it’s hard to imagine the shock caused by the first appearance in the early 1950s, amid the rubble and grime of postwar London, of these sharply dressed, tough-looking figures. The tabloid press had a field day, especially after the youngsters acquired the name “Teddy boy” in 1953 – from “Ted”, short for “Edward”, meaning someone who wore Edwardian-style clothing of long draped jackets, narrow trousers, slim ties and crepe-soled shoes. Anti-social behaviour, burglaries, car thefts, grievous bodily harm, race riots, even murder – all were laid at their door. “Ted” soon became a shorthand for anyone below a certain age who was causing trouble, or considered likely to do so.

Unlike other youth fashions, however, which evolved more gradually, the Teds were thrown onto the front pages by one particular flashpoint – and it set the pattern for most of the coverage they have since received. On July 2 1953, a trivial argument on Clapham Common between two groups of Edwardian-garbed teenagers rapidly escalated, leaving 17-year-old John Beckley dying of multiple stab-wounds. The resulting murder trial at the Old Bailey dominated the headlines that summer, with one front-page report in the Daily Express noting the pet name given to the gang members: “They became ‘The Edwardians’ or – as their girl friends preferred it – the ‘Teddy Boys’.”

The term was swiftly adopted by other news outlets. A June 1954 report in the Liverpool Echo of a near-fatal assault at a dance in Southampton noted that the accused appeared at his trial wearing “a grey-coloured draped jacket with a dark blue velvet collar, and an open-neck white silk shirt”; the piece was headlined “Teddy Boy On Stabbing Charge”. Bristol pub landlord Reg Brice told the Daily Herald that the clothing itself inspired bad behaviour, blaming his son’s recent conviction for drunkenly kicking in some shop windows on the teenager’s fondness for wearing a 17-guinea Ted suit: “Since my son bought that thing a year ago, his personality has changed. From a good, well-behaved lad, he’s become a Teddy boy.”

Yet the Edwardian revival in men’s clothing had originally been devised by Savile Row in the late 1940s, and been aimed at a much wealthier clientele. The Teds first appeared in poor districts of London, such as Elephant & Castle and the East End. There was then a crossover period in which well-heeled figures such as Cecil Beaton still favoured the Edwardian look while newspapers ran weekly reports of hooliganism perpetrated by teenagers in similar outfits. In June 1954, Beaton joked at a Foyles Literary Lunch that he had been approached in the street by a shifty-looking young Ted who whispered to him conspiratorially: “The job’s on tonight, with razors.”

Beaton was speaking six months before the first example of a genuine US rock record hit the British charts: Shake, Rattle and Roll by Bill Haley and His Comets. In much of the media, rock ’n’ roll was greeted with loaded references to “the jungle” and the “primitive”. Jeremy Thorpe, MP for North Devon and a regular 1950s television pundit, dismissed it on air as “musical Mau Mau”.

But rock ’n’ roll might have been made-to-order for the Teds, and the two became indelibly linked in the public mind after the newspapers ran articles about seat-slashings and “riots” at showings of Haley’s 1956 film, Rock Around the Clock. “A youth danced on the roof of a parked car”, the Manchester Guardian reported, while “another performed a ‘snake dance’ in a dazed, hypnotised fashion.”

Nonetheless, as the 1950s progressed, both rock ’n’ roll and the Teddy boys became a familiar, albeit much-criticised, part of national life. Fictional Teds turned up in television dramas such as A Likely Tale, in which the 48-year-old Robert Morley, portly and balding, played both a father and his Teddy-boy son; films such as The Ladykillers, featuring Peter Sellers in a velvet-collared grey drape; and novels such as Alan Sillitoe’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, whose chief character, Arthur Seaton, has a wardrobe full of lovingly pressed Ted clothing, which he takes care to put away neatly, even after a night on the sauce: “He started laughing, drunk to himself and all the world, until he crept upstairs in his stockinged feet, set his Teddy suit on the number-one hanger, and slept sounder than any log.”

A genuine Teddy boy named Gerrard Gibson even played a gang-member in the taut 1958 British film Violent Playground, as the Leicester Mercury reported. “Gerrard, wearing his best Edwardian suit, leopard-skin shirt and crêpe-soled shoes, was watching the film unit at work. When asked to sell his ‘outfit’, he replied: ‘You can’t have my best clothes unless I’m inside them.’” After only five years, the Teds were part of the cultural scenery.

Yet their increasingly comfortable image was to change radically in the late summer of 1958, with the Notting Hill race riots. The Daily Mirror ran a front-page headline saying “2,000 Riot – Gangs Invade ‘Colour’ Clash Area”, accompanied by a cartoon showing a flabby, thuggish Teddy boy, his hand holding an outsized flick-knife dripping with blood. A crudely drawn swastika was on the wall beside him, and the shadow of Hitler was whispering in his ear: “Go on, boy! I may have lost that war, but my ideas seem to be winning.”

The origins of the riots were far more complex – not least because of upper-class fascist leader Oswald Mosley deliberately stoking racial tensions in the area – but that shadow would follow the Teds for years to come. It was reinforced by their simplistically negative characterisation in Colin MacInnes’s popular 1959 novel Absolute Beginners, as well as a string of late-1950s television dramas which had already begun to characterise them as hooligans. These included the 1956 ITV play Teddy Gang, whose director David MacDonald branded it “tough, near-X-certificate television”, and, one year later, the BBC’s The Wharf Road Mob, set at an inner-city youth club frequented by a Teddy-boy gang. The impression conveyed to the public was that Teds carried weapons, and used them at the least provocation.

From punks to mods, Britain’s post-war youth movements have usually, in the course of time, been given their due by everyone from tabloid editors to academics. But for the Teddy boys, a working-class movement light on influential champions, redemption has since proved elusive. The image of the sad, ageing Ted, not the original teenage version, has been the one usually offered up. Think of Paul Shane’s character “Ted” in the late-’50s-set sitcom Hi-De-Hi (1980-88), wearing loud suits with velvet collars, and singing the rock ’n’ roll pastiche theme-tune Holiday Rock – despite being a man in his forties.

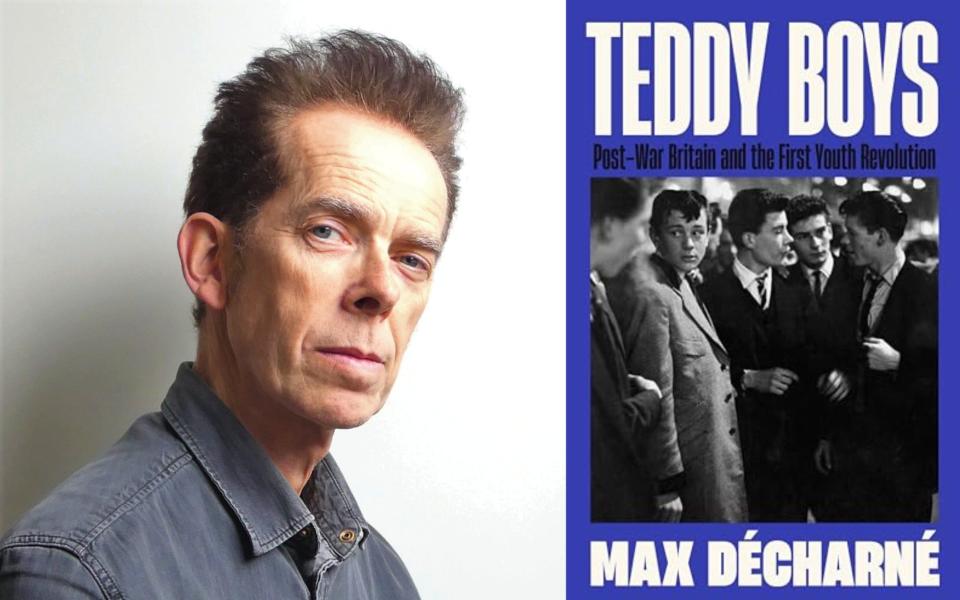

When writing my new book, Teddy Boys, I realised that the greatest difficulty to changing this image, and seeing the Teds afresh, is apathy. Their raw transformative power is no longer familiar to most of us: while the 1950s youth movements kicked the door down, these days we’ve seen it before.

Today, all manner of clothes and hairstyles – from bondage trousers to multi-coloured hair – hardly raise an eyebrow from passers-by. Teenagers 70 years ago, by contrast, were expected to dress like their own parents as soon as they drew their first wage packet; any show of individuality was both an affront to society and a new liberation. The Teds, then, caused a fundamental shift in the way British society viewed young people – and how that youth saw itself.

Teddy Boys: Post-War Britain and the First Youth Revolution by Max Décharné is published by Profile on January 25