‘I wanted to use violence in excess’: How women filmmakers reclaimed the revenge movie

Fatal femmes: Alice Lowe in Prevenge, Matilda Lutz in Revenge, Carey Mulligan in Promising Young Woman and Francesca Eastwood in MFA

(Kaleidoscope/Shutterstock/Focus/iStock)Content warning: This article discusses sexual violence.

Revenge is born of distrust. A distrust in the systems supposedly designed to uphold justice. For many, it’s a distrust that’s justified. And on screen, it’s one that translates into a cohort of bloody vigilantes seeking retribution by other means. The Oscar-nominated Promising Young Woman is the latest of these revenge-driven films to be praised by critics for successfully righting wrongs on screen.

Emerald Fennell’s directorial debut, which stars Carey Mulligan as the lip-gloss-wearing, gum-snapping avenger of her best friend, falls into the subgenre of rape-revenge. As the #MeToo movement continues to propel a public reckoning with sexual violence, and with the glaring lack of consequences for its perpetrators, such stories have become more relevant and profuse than ever.

Of course, it’s not a new genre. Rape has long been used as a film’s trigger event – historically, it’s the green light for a male character to gouge out eyeballs and chop off genitals, all the while occupying the moral high ground. That’s been true of throwaway flicks such as Taken, as well as highbrow fare (Ingar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring and John Ford’s The Searchers all pull focus on a father’s proxy retribution). In recent years though, these tales of men avenging their loved ones have been criticised as anti-feminist, making way for a vanguard of women characters leading the charge.

Promising Young Woman may be the latest and most high-profile of this new wave of women-led revenge thrillers, but it’s not alone in its subversion of a decades-old narrative. Cast back a few years and you’ll find a handful of women filmmakers have taken a stab at the typically nasty subgenre – previously dominated by male directors – and turned up new results, as well as new issues to debate.

Before Promising Young Woman, there was Revenge. Coralie Fargeat’s aptly titled French thriller was released in 2017, pre-#MeToo and a month before the Harvey Weinstein allegations came out. “The timing was strange,” says Fargeat over the phone from Paris. “But not a coincidence. I think I was unconsciously infused with conversations coming out at the time.” With a deft hand in her first feature film, Fargeat challenges her chosen genre from within – chewing up its tired tropes before spitting them out twisted, in all the wrong (or rather, right) places.

The film’s first scenes play out like a tacky cologne commercial. Richard (Kevin Janssens) is en route to a hedonistic weekend in the desert with his younger girlfriend Jen, played by a formidable Matilda Lutz. She is a walking – and barely talking – Barbie doll who lazily sucks on a lollipop in the helicopter’s back seat. The camera follows her body obsessively. Fargeat’s lens clings to her bum, stomach and mouth like sweat on skin. It’s so obvious that it’s laughable: a parody of how women’s bodies are depicted in horror movies – taut and glistening always, even when quivering in fear or drenched in blood. So far, so typical. But the teenage-boy fantasy turns nightmarish when Richard’s hunting buddies arrive at the villa. After one friend rapes Jen, she is chased out into the desert by all three men, pushed off a cliff and impaled on a branch, left to die. Only she doesn’t. When Jen survives and seeks revenge, Fargeat flips her camera as the men become the objects of Jen’s (gun) sight.

Staying true to its genre, Revenge is not a subtle movie. A film-studies class would have a field day. There’s Richard’s mirrored sunglasses that allude to the male gaze, a message that’s hammered home by the gouging out of eyes that follows. There’s the phoenix (an icon of rebirth) that’s left branded on Jen’s stomach from the logo on the beer can she uses to cauterize her gash. Subtle was never the goal. “I really think in terms of symbols,” says the director. “There’s almost no dialogue in the film so every visual element must have a strong meaning.” The genre itself leans into symbolism and imagery; “Revenge films are not to be taken literally.” Before she began writing, Fargeat compiled images and songs to set the film’s tone. Likewise, during the casting process for Promising Young Woman – another hyper-stylised film – Fennell sent Mulligan the script complete with a playlist and mood board. “These iconic images mean so much,” says Fargeat. “The audience won’t necessarily analyse them, but they’ll receive it in an emotional way.”

Reality was not a concern. “I wanted to lean into phantasmagoric elements so I could free myself from the rules and shoot the film in the way I was interested in shooting it.” She talks about Jen’s transformation scene as an example. After she de-impales herself, “she becomes like a superhero; she can walk around the desert barefoot and seems to not be scared any more”. In that quasi-superpower way, Revenge is reminiscent of Quentin Tarantino’s cult flick Kill Bill. Fargeat’s disinterest in realism extends to the film’s violence, which is extensive, gruesome, and extremely (extremely) bloody.

“I wanted to use violence in excess,” she tells me. But crucially, the violence depicted on screen isn’t the rape (Fargeat’s camera pans instead to Richard’s other friend watching television over the sounds of Jen’s screaming, nodding to the complicit violence of enablers). “I didn’t want this to be torture porn where Jen is the scream queen.” Instead, the film’s brutality is found in Jen’s injuries and the horrific acts she commits, physical expressions of the lasting trauma of sexual assault. “I didn’t need the violence to be totally realistic,” says Fargeat. “It’s a catharsis, some kind of fury and anger that is finally released. With genre films, you’re going places you can’t go in real life.”

Catharsis is a word that frequently crops up when defending revenge films against criticisms of gratuitous violence and a lack of realism. Could a 5ft 3in woman really overpower this slobbering git? Would Jen really have bullseye aim the first time she pulls a trigger? While the catharsis that Fargeat speaks of is more general – a manicured middle finger to rape culture – the LA-based director Natalia Leite’s was more personal, more painful. Leite’s 2017 thriller MFA follows different routes to a similar effect. After the accidental death of her rapist, art student Noelle (Francesca Eastwood) sets off on a dangerous course seeking justice, both for herself and for other sexual assault survivors. The film’s details are modelled on the director’s own experience of sexual assault in art school. As Noelle, Eastwood dons the same black hair and block fringe that Leite is still sporting on our Zoom call. During filming, Eastwood wore the director’s old college clothes. In the scenes where Noelle is seen drawing, it’s Leite’s hand that features. “It felt very cathartic and just really emotional,” says Leite of shooting the film, which was released four years ago.

The rape scene was particularly distressing to film, she recalls. But Leite had a clear idea of what she wanted it to look like, or rather what she didn’t. “Most revenge movies followed the same formula. The actual rape scene always felt a bit gratuitous – I think in part because you’re seeing the guy getting off and you’re seeing a lot of thrusting, so it feels pornographic,” she grimaces. “I was left feeling like, ‘Urgh, someone is getting turned on watching this.’” MFA departs from these films with a series of purposeful choices. The rape is shown but Leite resists the genre’s tendency to revel in depictions of sexual violence. Instead the camera stays on Noelle’s face. “We’re only seeing her and the torture of what she’s going through.”

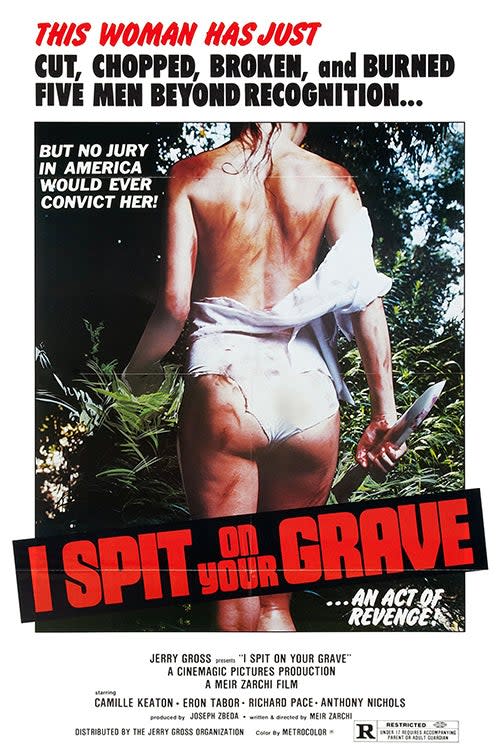

Compare this with I Spit on Your Grave. The ultra-violent 1978 film by Meir Zarchi (of which there is a godawful 2010 remake), about a writer who takes revenge, one by one, on each member of a group of strangers who raped her, has been called the “basic template” for these types of stories. Its prolonged rape scene is almost gleeful in its sadism, inviting audiences into a spectacle of sexual violence even as it ostensibly condemns the actions.

Leite also wanted to refigure people’s idea of what a rapist looks like. “It’s not the stereotypical man that’s running down the park in the middle of the night to grab you. It’s also not necessarily the drunk frat guy at a party,” she says. “Maybe it’s someone you have a crush on, who’s an art school kid that’s sensitive.” Breaking that mould is something Promising Young Woman makes strides in too. Fennell’s casting of affable Noughties crushes as would-be rapists brilliantly upends audience expectations, playing on decades-old impressions of “the nice guy”. Surely Seth from The OC wouldn’t do that. Surely.

This wave of women-led revenge narratives also took acquaintance rape – when the attacker is someone you know – seriously at a time when it wasn’t as openly talked about. “It sounds ridiculous today, right?” says Leite. “It’s amazing how much can change in the cultural conversation in just a couple years.” MFA is also one of the first places I heard phrases that have rapidly become red flags of rape culture. “Are you sure you said no and that he heard you?” a college administrator asks Noelle. “How much did you have to drink?”

Promising Young Woman has received loud applause and four Oscar nominations for its razor-sharp skewering of the revenge genre and rape culture in general. But four years ago, in the pre-#MeToo landscape into which Leite’s film was released, there were cries of “man-hating”. It seemed that while Liam Neeson was free to gallivant about, kill baddies and still be adored, the same understanding did not extend to women characters. Testing this capacity for empathy was something that preoccupied Alice Lowe, who stretched it to breaking point in her 2016 film Prevenge.

The pitch-black and riotously funny film – which Lowe writes, stars in and directs – sees a heavily pregnant Ruth descend into a rabbit hole, killing people at the apparent behest of her malevolent foetus. Initially, it seems her murder spree is part of a feminist crusade, perhaps retribution for an assault – something with which an audience could get on board – but then Lowe pulls the rug out from under us and we’re left watching a killer, full stop. “I wanted to play with the audience and see how far you can push them in their loyalty to this character,” she tells me over the phone. “I wanted it not to matter whether she was pregnant or grieving. That’s an easy out for any audience.”

Although there turns out to be no sexual assault or feminist agenda at its vengeful centre, Prevenge, Lowe tells me, is a revenge on society. “It was born out of an annoyance and a rage at how women are pigeon-holed for the way they look.” For her, that “look” was a ginormous baby bump. There are expectations that come with being a mother or not being a mother. Her character Ruth takes these expectations and weaponises them, expertly wielding them against those on her list. “It’s subterfuge, a kind of disguise in a way. It blindsides people because they think she’s going to be weak and they’re scared of hurting her, so it gives Ruth an extra bubble of protection,” explains Lowe, who was barely a month shy of her own delivery date when shooting the film.

While being pregnant isn’t a costume, the idea of playing with expectations is practically scripture in women-led revenge tales. In Promising Young Woman, Cassie’s fuzzy pink jumpers, blonde curls and love-heart jewellery belie a sardonic, guarded and ultimately ruthless persona. Just as Lowe’s Ruth leans into preconceptions of pregnant women as fragile, Mulligan’s Cassie smears red lipstick across her face as a guise of vulnerability.

Amid the awards buzz and reviews that have heralded Promising Young Woman as a searing portrait of post-#MeToo anger, there are critics who are not so enthused. For The New York Times, Jeannette Catsoulis wrote that the film “turns sociopathy into a style and trauma into a joke”. The same complaints were also lodged in regard to its predecessors, which some viewers criticised for flattening their characters into sexy avengers and dismissing real-life psychological fallout in favour of a fun, homicidal rampage. It is a legitimate debate. Revenge films, built on the bones of sleazy exploitation, are fraught with questions like these.

Watch these films and it is easy to experience the catharsis intended by their creators. It feels radical to see a rapist punished on screen when, in reality, so few are. It’s also a relief to see a woman dealing out the death blow, rather than her father. But as much as these movies gain their power from subverting a genre that in the wrong hands represents a film-making nadir – Michael Winner’s Death Wish series, for instance – it’s also this that makes them unable to transcend its inherent oversimplification: the suggestion that society’s most troubling issues can be addressed by an individual with a weapon. You can’t help but feel that something more nuanced is being lost in all that Pepto-pink. That being said, why should men have all the fun?

Read More

Promising Young Woman: Why Emerald Fennell’s complex revenge flick should win the Oscar

‘Torture the women!’: How horror’s final girls are turning the tables on misogyny