Vibe check: what does the most overused word of our era actually mean?

The most important people in the history of the word “vibes” are the Beach Boys. Before the release of Good Vibrations, in 1966, if you heard someone say “a vibe”, they were probably talking about a vibraphone – the xylophone-like percussion instrument with ringing metal bars, invented in 1916. The thought that a person could give off “vibes” was a niche, mostly hippy concept that Brian Wilson heard about from his mother.

At first, it was frightening. “[She] used to tell me about vibrations,” Wilson told a biographer, years later. “She told me about dogs that would bark at people … that a dog would pick up vibrations from these people that you can’t see, but you can feel.

“It scared me,” he said. “The word ‘vibrations’.” Wilson originally wanted to call the song Good Vibes, but his lyricist, Tony Asher, said it was a “lightweight use of the language”. Nevertheless, by 1970, John Lennon was saying it (“You give off bad vibes”), then Bruce Springsteen (“Hey vibes man!”), and, by 1983, Kate Bush (“Vibes in the sky invite you to dine”, in Blow Away).

Since then, the word “vibe” – and various promises to change it, check it, luxuriate in it – has become inescapable. A “vibe” can be an idea, a message, a connection between two people, an atmosphere, “off”, unquantifiable, a sensation as clear as the weather. Dressing nicely is “a whole vibe”; a “vibe shift”, as popularised by a 2021 New York Magazine article, is a coming cataclysm. (“Will any of us survive it?” the piece asked.) A day of bliss spent with the people you love is simply “a vibe”.

But, without anyone intending it, the popularity of “vibes” threatens to make it mean nothing. Jessi Grieser, an associate professor in linguistics at the University of Michigan, said that “vibe” had undergone a process known as linguistic generalisation, where its meaning had slowly expanded.

The New York Times asked last year: “Is crime that bad, or are the vibes just off?” Bloomberg described an economic downturn as a potential “vibecession”. Google announced that its maps will soon be able to perform “vibe checks” on entire neighbourhoods – with AI. The example provided was a trip to Paris. Imagine having your arrondissement “vibe-checked” into oblivion by a robot.

Peak vibes might have arrived last year in the form of a poster, on the streets of New York, during the city’s Democratic primaries. Suraj Patel, a 38-year-old lawyer and former Obama staffer, was running for Congress against two of the state’s longest-serving politicians. Thanks to a radical redistricting, the two incumbents, Carolyn Maloney and Jerrold Nadler, plus Patel were all vying for the one seat.

Patel, the outsider, started putting up a distinctive poster. There was a photo of him, in a blue business shirt, smiling widely, with large stylized flowers curled up and blooming around him. Campaign leaflets spoke of the cost of living, the climate crisis, abortion rights. But the poster had no policies, and no party affiliation. Along the top, it just said “Change the vibes”.

“I truly think it encapsulates the mood of the public right now,” Patel tweeted. “We don’t need more defeatism. We need happy warriors who are pro-abundance, pro-democracy, and pro-vibes.”

But what did it mean to be “pro-vibes”?

“It’s energy. It’s for the future,” Patel told the Guardian in August, ahead of the primary. “The design of that poster and the use of the word ‘change the vibes’ is exactly to change the vibes.”

Patel admitted that there had been “hand-wringing” about such a vibes-heavy poster. “People on my campaign were very skittish about using it,” he said. But the final design, to him, was perfect. “People of all ages are understanding this poster,” he said. “Whether they understand the term ‘vibes’ at some level – maybe they don’t. But they get it, they get the concept.”

For some, “vibe” is an entire profession. Chris Low works as the global head of vibe for the graphic design technology company Canva, which had a recent market valuation of $US25.6bn. “I always say the head of vibe with a slight smirk on the side of my face, knowing that people will think that’s quite a funny job title,” Low said. “I get a lot of people reaching out to me on LinkedIn just for the purpose of commenting on my job title.”

Before he was in charge of vibes, Low was a restaurateur and chef, who ran a cafe near Canva’s offices in Sydney. Canva hired him because two of the company’s founders loved “the vibe” of his cafe. “They’d come in every morning for their coffee, and they heard I was selling, and they said, ‘Can you bring the vibe from your restaurant into our office?’” Low said.

“I didn’t know Canva at the time,” he added. “It seemed quite strange.”

Now, Low heads up an international vibe team of 60 people, who are known as “vibies”. They are responsible for social events, food, “activations” (the company’s name for small pop-up activities like cooking classes or Friday drinks), and the design and maintenance of the office’s physical spaces. Last year, the vibe team performed over a thousand vibe-related events.

“When I first heard the word, when Cliff [Obrecht, the company’s co-founder] said to me, ‘Bring the vibe of your restaurant,’ I almost didn’t know what he meant.” Low said. He has now been the head of vibe for seven years. “In the tech world, that’s a long time,” he joked. “Now you’re seeing vibe teams popping up left, right and centre these days.”

The whole vibe

There is undoubtedly value in having a word for the unquantifiable. The German word “Zeitgeist” was loaned into English, in 1848, perhaps precisely because it encapsulated what we were missing before “vibes”. A classically German compound noun, it literally means “time-spirit”, and the broader German concept of “Geist” itself is maybe even more modern-day vibes-ey – combining to make “Volksgeist” (“national spirit”) and “Weltgeist” (“world-spirit”).

Part of what is driving vibes could be that everyone is actually feeling it. On 11 February, the New York Times crossword ran a clue: “Emotional assessment of one’s surroundings, in lingo”, nine letters. The answer was “vibe check”. Like it or not, part of the contagiousness of “vibes” is that everyone seems to understand, on some level, what it means.

Rap culture and Black vernacular might have been early pioneers. “This is the case with lots of our common slang,” Grieser said. “Most of it comes from Black language practices.” Quincy Jones launched Vibe magazine in 1993; A Tribe Called Quest released Vibes and Stuff in 1991; R Kelly’s debut single was She’s Got That Vibe, also in 1991; and one of Kendrick Lamar’s hits of 2013 was Bitch, Don’t Kill My Vibe.

According to Grieser, the linguistics professor, when “vibe” and “vibrations” first took off, the word was usually collocated with emotions – specifically “good” or “bad”. Using the Corpus of Contemporary American English – an archive of texts used to understand how English is evolving, spanning roughly a billion words, from the 1990s up until 2019 – Grieser found a slow shift to a more amorphous use of “the vibe” or “vibing”. “Things can be ‘a vibe’” and “the really recent move is ‘whole vibe’”, she said. A more recent dataset, of web-based newspapers and magazines from 2010 until 2021, showed “vibing” rising significantly in 2021. “I wasn’t able to find any sort of watershed that seems to have started that or a single spot,” Grieser said. “But we do get that big spike in 2021.”

It’s this use of “the” vibe that has started to snowball with new meanings. “We use that actively,” Low said. “Sometimes, it’s enough to say that a particular behaviour decision isn’t ‘the vibe’.”

But even though he is the head of vibe, his company has not defined to him what “the vibe” is. “To box it, to draw lines around it, I don’t think is really conducive,” he said. “We facilitate and allow it to grow naturally.”

“It’s not ‘the vibe’ to be one certain type of personality. We don’t assume that vibies are always extremely extroverted,” he added. “It actually can be ‘the vibe’ to sit down quietly and share a game of cards.”

Grieser said the word’s earlier links to mysticism were also disappearing. “If you look at some of the sources from English corpora, it’s E! Online, the BBC, the Daily Mail, the Independent, ESPN – this is no longer the countercultural weirdos who are using ‘whole vibe’.”

Patel, the New York political candidate, denied that “vibes” was becoming meaningless. “I don’t think it’s losing meaning at all – I think people are finally picking up on the meaning,” he said. “You know, the energy of the moment, the energy of a room or someone’s personality or something … It’s capturing this nearly ineffable word or description of the generalised feeling of something. That’s what we were going for. And I don’t think there’s a better word out there to encapsulate it right now.”

An ancient obsession

While the use of “vibes” as a word might be recent, our obsession with intangible vibrations dates back to antiquity. Ancient Greek philosopher-scientists conceived the idea of “quintessence”, a “fifth element” that made the world work. Mystics and esoterics in the early 20th century claimed to be able to see “auras”: normally invisible fields of energy around people. The ancient Chinese concept of “qi” – the life force of living things – is also among the first to include the inverse: a concept of “negative qi”, which can include emotions like fear or being socially anxious or awkward. Similar, really, to “bad vibes”.

Trying to explain feelings and energies we can’t see has been an object of religious faith, and to an extent, a field of scientific discovery. The sound of the vibraphone and the music of Good Vibrations are, after all, actually vibrations.

Before “vibes” was a job at a tech company, it was a word of deep import for the New Age movement. Oleg Yankelevich is a New York-based reiki practitioner, who works with human and animal patients, including dogs, cats, and sometimes horses and hamsters. Yankelevich said he first heard the word “vibes” when he started practising reiki 22 years ago. “Back then, the word was not used a lot, as it is now.”

Now, people come to Yankelevich complaining that their vibes are “not in the right place”. They leave saying “I feel my vibe has changed”. “It’s not so much that it’s being overused, but that the term has been growing,” he said.

For Yankelevich, “vibes” are real, not just slang. “If they say that this party is ‘a vibe’, then that means they are picking up on a certain energetic vibration that’s going on and is giving them a certain feeling,” he said. “In terms of wellness and energy work, there are similarities.” (But if someone says an outfit is “a vibe”, then “it may be just a term that they use as a filler”, he added. “They might not necessarily be aware of what the word means.”)

“If you think about it, vibrations are all around us,” he said. “They’re in everything, and they’re everywhere.” In quantum mechanics, “everything is described as being made up of a vibrational molecule,” he said. “Everything releases some kind of a vibration.”

Dr Nick Herbert, a physicist who was an early researcher in quantum mechanics – and who studies the afterlife and human consciousness – said he would consider whether real science could be behind the idea of “vibes”.

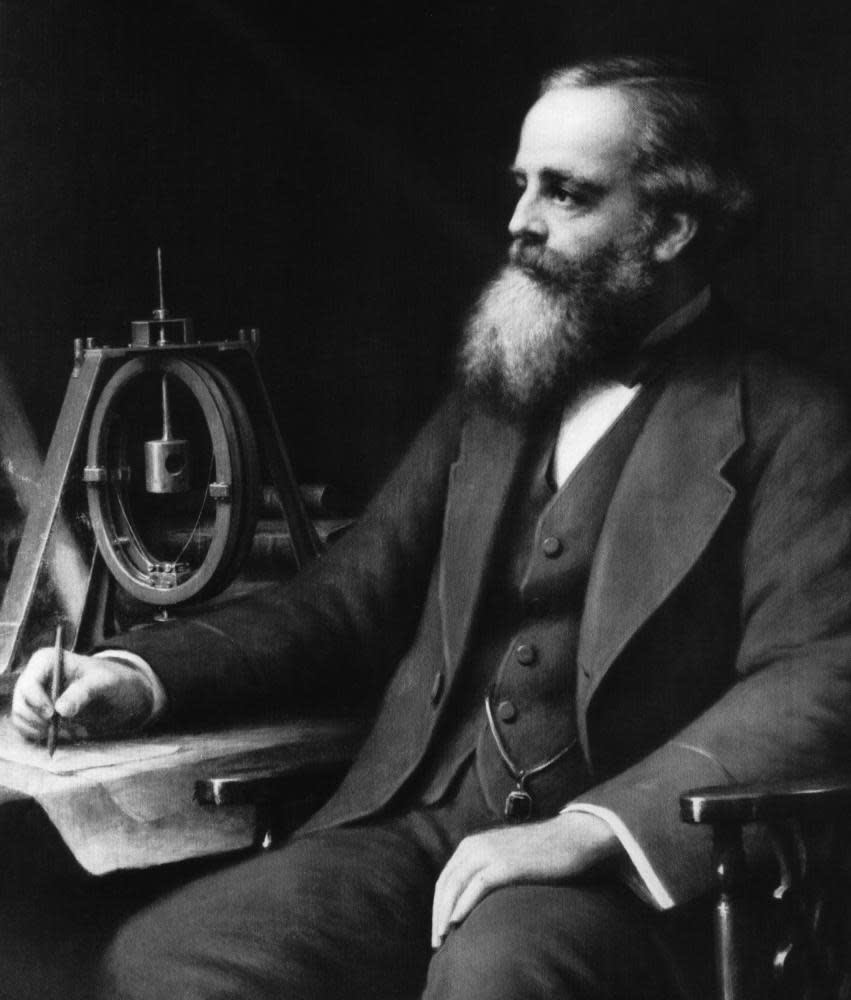

“One of the most important events in the history of vibes was James Clerk Maxwell’s theoretical discovery that light is an electromagnetic wave vibrating in a narrow spectral band, implying that there are other EM waves invisible to humans vibrating at frequencies higher and lower than RGB,” he said. “I would guess that the notion that we live in a vast ocean of invisible radio waves was one of the main inspirations for vibes, for ‘getting on the same wavelength’, for ‘being in tune’.”

Could there, then, be a scientific basis to vibes?

“To really touch the truth of what good vibes between souls might mean, we would have to answer the question: what is it that is doing the vibrating? What is the medium, in other words, in which vibes vibrate?

“No one has the slightest notion how to answer this question. It probably, in my opinion, has nothing to do with quantum mechanics. Which is now, like radio once was, the hottest science fad for some people to dress up their deep ignorance – (our deep ignorance – in phony knowledge-sounding words.”

Yankelevich said “vibes” was “a universal word, in a sense … People apply it differently based on their given situation. And I think that’s a fantastic thing.”

Grieser sketches a slightly gloomier picture. “It’s hard to get much broader than the space that is currently occupied. We just kind of mean ‘the state of affairs’.” She added: “I mean, New York Times headline, that’s kiss of death for a piece of slang.”

But to Low, “vibe” is unfairly maligned, and it can mean something genuine, human, and beautiful. “I feel like the word ‘vibe’ has this kind of shallow connotation,” he said. “[But] what makes us tick, what connects us, what creates that kind of sense of community changes over time. And that doesn’t make it shallow.”

“I love the word ‘vibe’,” he said. A job by any other name wouldn’t be the same.