‘You’re very fat up here’: was dance god George Balanchine a controlling monster?

‘I don’t have a past. I have a continuous present,” said the great Russian-American choreographer George Balanchine, a great believer in forward motion. When Balanchine’s health began to fail, in his mid-70s, he resisted making a will, not thinking that the hundreds of ballets he had created would live on without him. When the IRS posthumously valued his repertory, it decided that the maximum shelf life of even his greatest ballets was just 15 years.

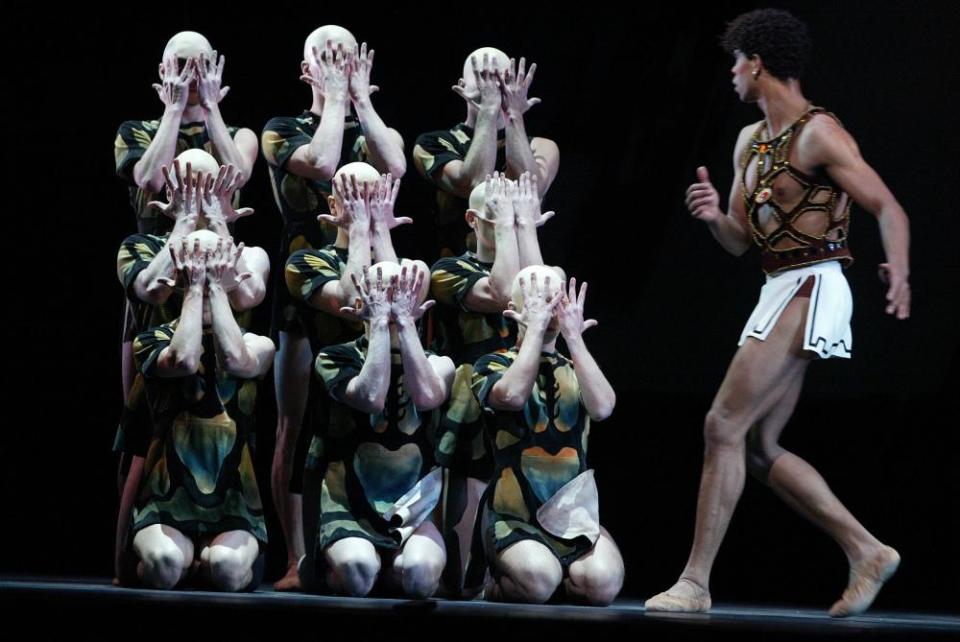

Yet today, almost exactly 40 years after Balanchine’s death, his works are as popular as ever. New York City Ballet (NYCB), the company he founded, has just announced its 75th anniversary season, with dozens of performances of his works. Masterful ballets such as Serenade, Symphony in C and Agon are still regularly danced around the world. This summer, the Australian Ballet comes to the UK to perform his Jewels. When Carlos Acosta marks his 50th birthday on stage in July, it is Balanchine’s Apollo that he will dance.

He didn’t want his female dancers to have boyfriends – suitors had to wait out of sight in a restaurant over the road

People are still talking about him, too. Last year, dancer turned historian Jennifer Homans published Mr B (as Balanchine was known), a vivid biography of the choreographer, chronicling his incredible life story: from Imperial Russia, dancing through war and revolution, near-starvation and TB; his escape to Weimar Berlin and 1920s Paris; and working with the Ballet Russes and London music hall. In New York, as well as founding NYCB, he established the School of American Ballet (SAB), defining a style that shed the staid trappings of classicism, the fairytale stories and elaborate costumes, to create something faster and stronger that captured the dynamism of 20th-century New York. His is a story of “immense creativity and imagination”, says Homans, as he “managed to make something of great beauty out of a century that was full of suffering and death”.

At the same time, there has been a recent wave of voices questioning the dominance of Balanchine’s ideals and the culture he forged. The podcast series The Turning: Room of Mirrors delved into ballet’s darker side, with some startling stories of the lack of boundaries between personal and professional relationships at NYCB. Writer Alice Robb, who studied at SAB in the 2000s and felt the power of Mr B’s influence, published the book Don’t Think, Dear (a Balanchine quote), tracking the fates of her classmates dealing with eating disorders, pain and injury – and tracing the way they absorbed damaging lessons from ballet into their lives. It’s possible to see Balanchine as both a god and a bogeyman, responsible for everything that’s wonderful or wrong about ballet. Of course, that’s far too simplistic.

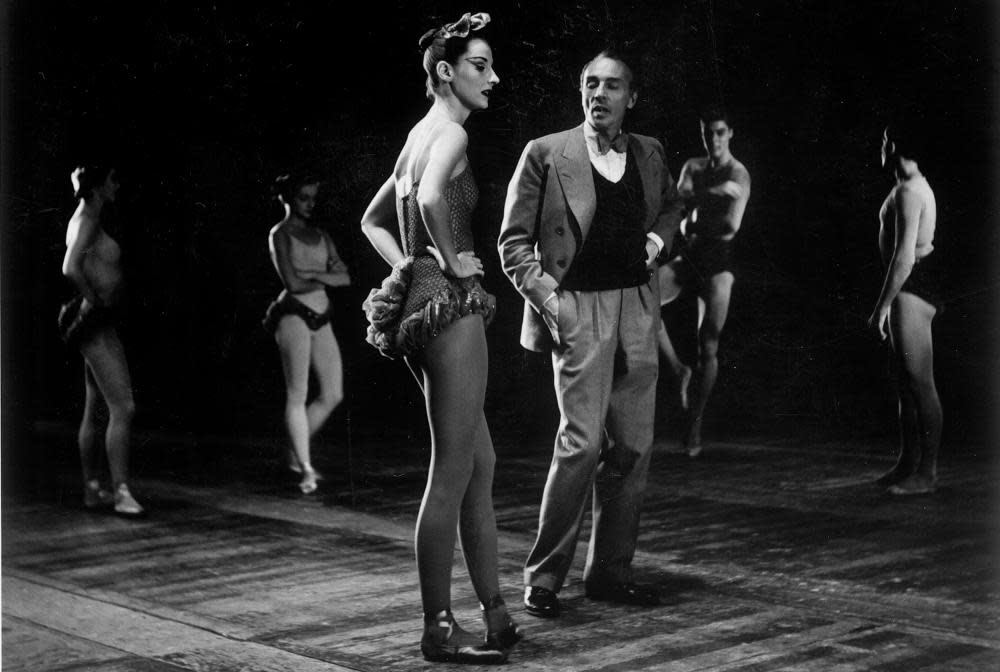

What’s true is that his influence is very much alive. No more so than when talking to the 80-year-old force of nature that is Patricia Neary, who danced for Balanchine in the 1960s and now stages his works around the world. She speaks as if he is there in the studio. “He wants that,” she’ll say. “Yes, that made him happy.”

“He was a genius choreographer,” says Neary. “Musicality? Incredible. Energy? Incredible.” He gave everyone wonderful material to dance, she says, even the back row of the corps de ballet. “When I teach his ballets, I see in the dancers’ faces how much they love the works.”

Homans trained at SAB and describes Balanchine’s deep musicality. “The way in which the physicality merges with the music is unusual,” she says. “It’s so connected, almost like the music and the choreography and the dancer are moving in and out of each other, in ways that are both structured and free.” Balanchine pushed the body off centre, challenging physics: Homans talks of “energy racing through the body in complicated patterns and oppositions that make it possible for you to move in bigger, clearer, more ambitious ways”. It meant legs going higher, angles riskier, momentum streamlined, speed escalating. “Pow! Bang!” he implored his dancers. “It was this idea you’ve got to wake up and stop sleepwalking and be fully present,” says Homans. “Perfection wasn’t the point. It was to be more alive in that moment.”

I adored this man. I adored him as a choreographer. He was incredible to be around

Who wouldn’t want that? It’s why Balanchine inspired a cult-like devotion. Erika Lantz, presenter of The Turning and a serious dancer herself in her youth, interviewed numerous ex-NYCB dancers. “It was so interesting the religious language people use to describe Balanchine,” she says. “When you’re creating beautiful art, it feels like you’re connecting with a higher power. I get it. But just how many people said he was like a god for them – that really struck me.”

Alongside that went an idea of dancers “as suffering saints”, Lantz adds, “which can very easily slip into seeing suffering as a good thing”. The Turning podcast suggests it was the company culture to centre a lot of power in one person. In 2018, Balanchine’s successor Peter Martins retired following claims of verbal and physical abuse in an anonymous letter. Martins denied the claims and an NYCB investigation did not corroborate them. When current directors Jonathan Stafford and Wendy Whelan took over, Stafford said: “We both will really be working on the cultural elements of the company.”

“Ballet is woman,” Balanchine famously said, and he was effusive about his love of women. He married four of his dancers, and had relationships with more. Dancers were the essential tools of his art. As a religious man, he saw them as angels, but he didn’t see them as rounded people who might have their own needs. He could be controlling: he didn’t want his female dancers to have boyfriends; any suitors would have to wait in the restaurant over the road, out of sight.

He became obsessed with dancer Suzanne Farrell, 41 years his junior, and when she married another dancer in the company, he took their roles away from them. And he certainly didn’t want women to have babies. It was all about the work and the work was flat-out. “He wanted 100% energy all the time,” says Neary. Homans adds: “He used to say, ‘What are you saving it for? You might be dead tomorrow.’ It was not just a saying, it was truth. He did almost die several times [in Russia]. And you didn’t take life for granted.”

“Balanchine would treat his class as a laboratory to see how much the human body could do,” says Robb, and that could have consequences, in terms of injury and burn-out. Attention to dancers’ physical and mental health has progressed significantly since Balanchine’s time: nobody’s banning dancers from having boyfriends any more. But Lantz warns of an exceptionalism that can grow around ballet: “If these things happened in any other work environment, you’d be like, ‘Wait, what?’ Acting like we’ve been chosen, we’re lucky to be here – I think that elite feeling around ballet makes it potentially more prone to abuse situations.”

Neary says Balanchine was really a shy, timid man, not comfortable around a lot of people. But when he spoke, he said what he thought. Balanchine was certainly not solely responsible for the trend for dancers growing skinnier over the 20th century, but he could be blunt about his preference for a particular ultra-slim body type.

“The weight thing was a big problem,” says Neary. There were a lot of eating disorders among the dancers in her time. “He could easily destroy a person’s confidence,” she adds. “When I was first in the company, he came up to me and touched my neckline and said, ‘Oh, you know you’re very fat up here.’ He wanted to see bones, and I remember thinking how weird that was. See – that would not be allowed nowadays.” But she loved dancing for Balanchine: “I have to be frank with you, I adored this man. I adored him as a choreographer. He was incredible to be around.”

Balanchine’s legacy? Beyond the catalogue of brilliant dances, it’s complicated. Robb thinks some of his messages have been distorted. “Even the title of my book, Balanchine said, ‘Don’t think, dear, just do.’ He could have said this to a dancer who was overthinking – it could have been a really helpful corrective. But that gets calcified and passed down as just, ‘Don’t think.’”

No one’s calling for Balanchine to be cancelled – after all, the issue of rigid physical ideals spans the whole of the ballet world. But we should, says Robb, carefully consider what has been passed on. “Whether you want to apply the standards of now to the past, I don’t know,” she says. “But we can certainly apply the standards of now to now, and look at how these things are filtering down. I think there’s still a lot to celebrate – and a lot that can change.”