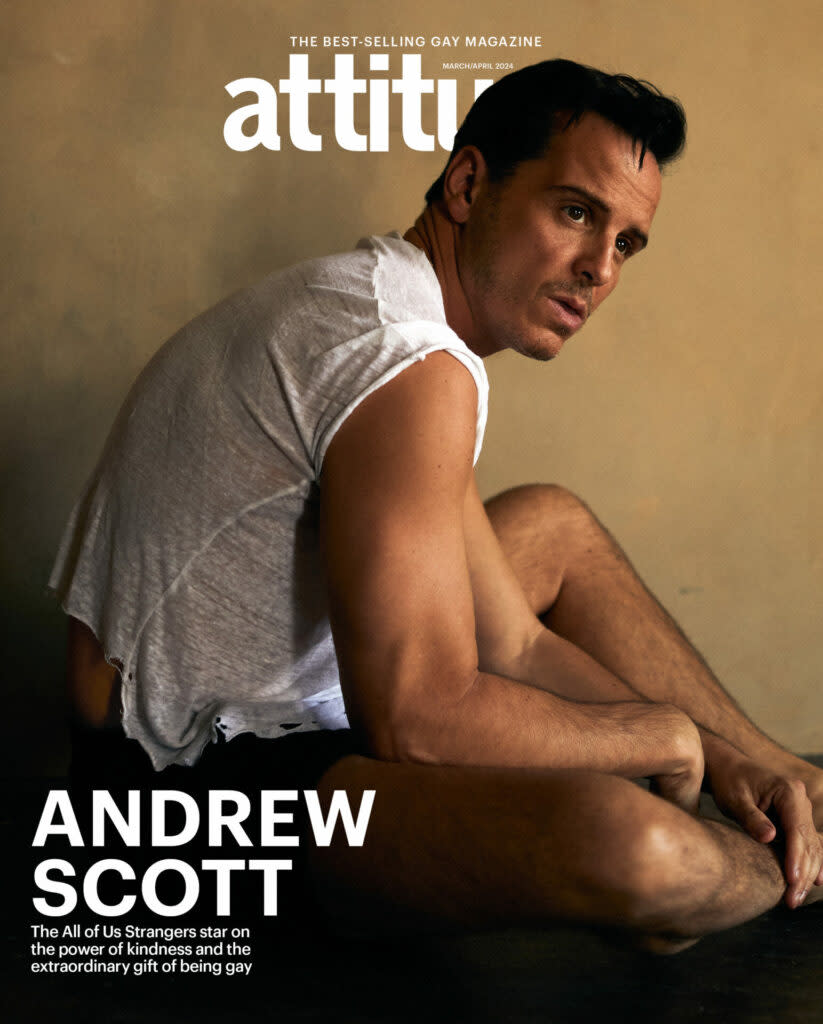

All of Us Strangers’ Andrew Scott: ‘It’s painful and it can be lonely being gay’

When it was announced that Andrew Scott and Paul Mescal would be starring as lovers in All of Us Strangers, a film written and directed by Andrew Haigh, fans were buzzing on social media about what the combination would deliver. This was no surprise: Andrew Scott – already a celebrated actor from roles such as Moriarty in Sherlock, the ‘hot priest’ in Fleabag, and Gethin in the incredible 2014 film Pride – and Paul Mescal (Normal People, Aftersun) are the definition of queer catnip. Under director Haigh’s masterful eye, the end product is an enthralling exploration of what it means to be queer in today’s Britain. Even ahead of its general UK release, the film has already made an impact and literally shifted the language we use about gay/queer representation on screen.

Haigh – acclaimed for past feature films Weekend and 45 Years, as well as HBO series Looking – has crafted a tender examination of love in the shadow of shame. An enigmatic dive into the pain and pleasure of finding affection in another man through the constrictive confines of emotional isolation, All of Us Strangers excels on so many levels.

The premise: forty-something Adam (Scott) meets Mescal’s twenty-something Harry, and the pair begin a love affair that has Adam revisiting his childhood home and conjuring up the ‘ghosts’ of his dead parents. And no, that’s not a spoiler, it’s just the opening scenes of a film that examines a love affair between two gay/queer men of disparate ages whose very different life experiences have brought them unexpectedly together. What happens next? Well, that’s for you to discover in a movie theatre near you. Essentially, All of Us Strangers is one of the most enthralling films of the 21st century to explore British gay identity, and Scott delivers quite possibly the performance of his career to date, one that dances between visceral suffering and emotional vulnerability.

Here, Scott talks to Attitude about bringing his character Adam to life on screen, working through shame, and the power of sex as a means of communication.

Cliff Joannou: A good place to start is to say that I really related to the film. I grew up in Croydon not long after director Andrew Haigh did, so the environment and era that it was set in really resonated with me.

Andrew Scott: You’re joking me.

For real. Even that shot with you as your character Adam walking through the Whitgift Shopping Centre, I was like, ‘Oh, that’s a little bit close to home.’ That’s exactly what it looked like when I was a kid. What resonated most with you in the story? For me it was very much the setting and location, being a young child in the UK after the worst of the AIDS crisis.

I suppose it was the dynamics within the relationships, that was what I found most authentic. And there’s two storylines within the movie, and both of them I found to be really, really beautiful and very actable. The scenes between Adam and his parents are genuinely extraordinary. And what’s so lovely is when I was in LA after the film had come out, and audiences had started to see it, and I’m really getting such a strong sense that people really do appreciate the nuance of the film.

I think the chief value of the film, for queer audiences particularly, is that it recognises that the dynamic within families isn’t always necessarily as dramatic, perhaps, as it is portrayed sometimes in stories about coming out, in the sense that it’s not fully embraced acceptance and nor is it outward rejection, but for a lot of queer people it’s somewhere in between, so that brutality and intolerance and doubt can exist alongside real love within families.

Absolutely. I like how frank the conversations are between Adam and his parents. I also like how early the conversation about Adam’s sexuality comes up with his parents.

What I love about that scene is that he doesn’t want to come out to his mum, he doesn’t want to have a coming-out scene. He’s a man in his forties, and he’s lived a life on his own for 30 years, so he wants to tell her about himself, and that includes, of course, him being gay, so he tries to be offhand about it, but also, I think my challenge was to show that he deeply cares what she thinks as well. And when she starts to be loud and wrong and reveals some prejudice in her questions, it enrages him.

But I think that exists alongside a real deep need for her to accept him, too. I think that scene is just so beautiful because it’s something, of course, that he’ll have thought about given the fact that he lost his parents 30 years ago. One of the things that I find really moving is when people talk about having lost their parents and never having come out to them before they died. I’ve talked to 60-year-old men who say, “I never got to do that.” And I think that really takes up a lot of people’s time.

Did you discuss with Andrew [Haigh] any of Adam’s wider backstory or did you create one for yourself? Where had he been in that time in between?

Not with a huge amount of detail because I suppose I thought of what benefit was that going to be. There were certain things I sort of thought about a little bit, but my biggest challenge, and all of our challenges, was to make those scenes as authentic as possible. We shot in Andrew’s childhood home, and that was such a brave thing for him to do. And I felt very much that if I were to think about any backstory, I wanted to think about my own; I wanted to bring my own stuff. To bring not necessarily my own biography, because it differs a huge amount from the character’s, but certainly my own emotional biography, as I call it.

It feels like such an extraordinary privilege to be able to play a character like this. And I wanted to give as much of myself because it was cathartic for me. I never thought that I would be able to watch a film like this, let alone be at the centre of it, so I wanted to be able to take that opportunity to express myself in some way. Why pick an imaginary backstory from somewhere else? I wanted to bring as much of myself as I could, because I feel like that’s what the audience is going to relate to the most.

There’s a bit early in the film when Adam meets his parents’ ‘ghosts’ for the first time, and he says, “Everything’s different now.” It’s such a powerful line as it highlights the character’s inability to let go of the past because doing so means he has to confront his present unhappiness.

Yes, exactly. Well, I suppose one of the best things that you can do as an actor is to say things to feel one thing but to say something else. That’s always what you want as an actor. A lot of the real interesting lines in the film are where people are saying one thing but meaning something else. When Adam says, “Everything’s different now,” I’m not sure that he fully believes that. He believes it in some way. But one of the things that I really love about the story is when Paul’s character of Harry talks about his estrangement from his family and he’s somebody who’s in his twenties.

I’m not sure the generational difference between Adam and Harry is the most interesting thing about the film. I think one of the big changes, of course, is the presence of Aids, when Adam would’ve been growing up. I certainly know that the shadow of Aids was very looming when I was growing up in the nineties. And, of course, that’s going to affect the way we think about sexuality in the sense that we’re going to feel like we’re going to be punished for being physical or for expressing love.

There’s another impactful moment where Adam says, “I thought if I fucked anyone I’d die.” It took me a while to get my head out of that space and allow my sexuality to be something that I enjoyed and recognise that it was not a threat to my life. How was your journey to finding peace with your sexuality?

Oh, it’s one of the wonderful things, the emancipation from that. I feel so incredibly… I suppose I just enjoy being gay so much on so many levels, I think it’s such a wonderful thing to me. It’s an extraordinary gift to my life and just to be able to see the real beauty in being gay is completely wonderful. The older I get, just the more I feel so lucky to have been born gay and that pervades my life in the sense of all my friendships. I have so many amazing queer friends in my life now that I just adore.

What’s very sad for some of us is that we avoid those kinds of people when we are shredded in our own shame. To be around other gay people highlights something that you don’t want to see, but when you do want to see it, it becomes completely wonderful. I feel such a huge sense of camaraderie with other queer people now, and without sounding too hippy about it, I feel like I just want to spread that love and positivity in our community because we’ve come such a long way, and it’s important that we are kind and look out for each other and celebrate how uniquely different and how fucking wonderful that can be.

That’s beautiful. I remember when I was younger and less comfortable in my identity, I avoided going to Pride, I felt it was a little bit too in my face. Now as I get older, I go there with my nieces, and we watch the parade, and there’s a tremendous sense of healing that comes with being around the community. And the broader the community gets, the more all these letters in that ever-expanding acronym stand out, the more beautiful it gets.

When I see two people of the same sex holding hands walking down the street, I’m like a little weirdo. I’m smiling at them. They’re like, ‘What’s that dude smiling at us for?’ Because I just think it’s so wonderful. It’s easy what you say about everything is different now. It’s something that I always feel when people say, “Oh, it’s 2024, you’ve got to get with the times.” I always find that preposterous because, and I mean this so vehemently, that different forms of sexual identity and gender identity have existed since the beginning of humanity. They have existed and will always exist until humanity ends. In 2084, they’re going to look back at us and think, ‘My God, those people were so old-fashioned.’ Sexuality, that’s not a fashion, it’s a natural state of being.

When I watch the relationship between Adam and Harry, there’s no point at which you feel like the sex scenes are being played for the audience’s titillation. It is one of those kind of rare sex scenes that actually drives the narrative forward, that it is important to the story.

Sex is just communication, isn’t it? It’s just physical communication rather than verbal communication. And what needed to be communicated is how I think we see Adam as somebody who hasn’t been touched by anybody or touched anybody in a long time, not just sexually, but he needs affection from his parents, and he needs love and sex and affection from his lover. And I think just seeing that tentativeness and the way Paul plays a character who’s a bit more sex-positive, so to speak… Their communication is really strong in that scene. I’m so proud of it. I really am because I feel like they represent the characters so beautifully.

How did you arrive at that point of playing those scenes in that way?

We didn’t over-rehearse it. We knew that those scenes, particularly the early ones, had to have a sort of frisson. And we had an intimacy coordinator, which can be very helpful for the simple reason that if you’re able to talk to somebody about your fears or what you want to show, what you don’t want to show, or what you think it should be and what the narrative of the storyline is, you have that base of safety. It actually makes you feel like you can do whatever you want. Because frankly, you just know that if there’s something that you don’t like, you’re contractually protected, and it won’t end up in the movie.

Andrew [Haigh] is really good. Sometimes when you do sex scenes, it can be like, ‘Oh my God, D-Day.’ And you are a bit nervous, of course, because you take your clothes off in front of strangers, but he’s like, “It’s just another scene,” so you don’t want to overdo it. But chemistry is a really interesting thing. You’re basically just listening to see what the other person is doing physically in the same way you would in a dialogue scene. And you can talk about that as much as you like, but until you’re actually there, it’s not alive in that way, so it’s just about listening, but just listening with your body, basically.

There’s a line in the film where Adam tells Harry, “Things are better now, but it doesn’t take much to feel the way that you felt.” Is there an instance where you remember, ‘Oh, that’s the first time I was made to feel shame?’

I don’t think that there is one particular point, but I do think if we could erase the assumption in our society that everybody is straight until proven otherwise, it would make an enormous difference to people. And by that, I mean that we don’t say to our six-year-olds, “You’re going to marry a princess, and have you got a girlfriend?” I remember when I was a teenager and people said, “Have you got a girlfriend?” I would say no, and I wasn’t necessarily lying, but you feel like you’re lying by omission.

For me, what happened is that you desexualise yourself slightly. And I think that what happens for a lot of teenagers is that there’s a conspiracy of silence around you, and that is a lonely place to be. And I think that’s where we become very hardworking, that we pour our energies into something completely different in order to correct what we imagine is a flaw in our character.

Some people go the opposite [way], where they become self-destructive; you can be super hardworking and incredibly ambitious, or you can just completely go off the rails. You think, ‘Well, I have been rejected, so I’m just going to go crazy.’ It affects our psychology in so many different ways. It may not necessarily be something that’s actually happened to us; it could be just forecasting what you think might happen, and that forecasting happens when we read about prejudice or other horror stories. The way the media talked about gay people when I was growing up was absolutely disgusting and fearmongering, and I still think we have to be very careful in not just the media, but in the way that we consume media and what we stand for. That we call out that kind of cruelty and intolerance. Language matters.

When we read the opposite, when we read positive things or see representation on screen, when we see ourselves, we think, ‘Oh, well, we can forge a way in the world.’ That’s why I think a movie like this, it is so incredibly important because it’s incredibly compassionate and tender, but it also doesn’t erase the fact that it’s painful and it can be lonely being gay. And there’s a certain thorny path that we all have to go to in order to find love, not just in another person, but in ourselves.

The clip from the Hollywood Reporter where you talk about the use of the term ‘openly gay’ went viral and has likely changed the way we refer to out queer actors in future forever. What went through your mind when you saw the reaction to that?

There’s something about that phrase that makes me uneasy about what it implies. Particularly now. You don’t put ‘openly ’in front of most attributes or characteristics. And I think we should maybe look at retiring it. And I know I’m not alone in that. The response to the clip reflects that. I do understand that historically we need a word to recognise the fact that there are sometimes people that are gay but for whatever reason aren’t able to be open about it. I totally get that. And so, I just feel the word ‘out’ does that. It’s just simpler. It does the job, and with less implications.

All of Us Strangers is out on 26 January. Pre-order the March/April issue of Attitude here.

Words Cliff Joannou Photography Ramon Christian/@ramonchristian.photo Grooming KC Fee/@kcfee Styling Warren Alfie Baker/@warrenalfiebaker Post production Simon Courn/@simon_courn

The post All of Us Strangers’ Andrew Scott: ‘It’s painful and it can be lonely being gay’ appeared first on Attitude.