Step inside the world’s largest nuclear bunkers

Supersized sanctuaries designed to withstand nuclear attack

Jesse Alexander / Alamy Stock Photo

Billionaire Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg might be building a 5,000-square-foot refuge beneath his Hawaiian compound, but that doesn't come close in size to the world's biggest bunkers. Built by governments and concerned citizens alike, these spectacular sanctuaries are kitted out with everything you might need to survive a nuclear attack.

Read on to explore some of the largest shelters on the planet, from Cold War relics to modern-day prepper communities.

Central Government War Headquarters, Corsham, UK

Jesse Alexander / Alamy Stock Photo

The Central Government War Headquarters is a secret underground city, built 100 feet beneath the village of Hawthorn, near Corsham, Wiltshire.

Sprawling over a massive 35 acres, the site was originally a quarry before it became an ammunition depot between the First and Second World Wars. In 1941, barracks were added, followed by a subterranean factory building aeroplane engines for the Bristol Aircraft Corporation, hiding its work from the Luftwaffe.

Central Government War Headquarters, Corsham, UK

![<p>Olga Lehmann / Wikimedia Commons / MoD / Crown Copyright [Open Government Licence 3]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/MUa_sv.PmDgXO4pB17sx2A--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/41bdddfc0b81252773571e25a3716738)

Olga Lehmann / Wikimedia Commons / MoD / Crown Copyright [Open Government Licence 3]

A gloomy place to work, Chilean-born British artist Olga Lehmann was hired in 1943 to paint murals on the walls of the underground factory. They had to provide Lehmann with the paint as materials were hard to come by during the war. As a result, all the colours found in the murals were those used to paint British aircraft.

Lehmann painted the walls of six canteens in the subterranean factory, which took her and an assistant around eight months to complete. Still in good condition today, the artworks are Lehmann's only known surviving murals and are Grade II* listed due to their historical significance and rarity.

Central Government War Headquarters, Corsham, UK

Chris Ware / Keystone Features / Getty Images

In 1955, as Cold War tensions ramped up, part of the Corsham Tunnels was earmarked to become the Central Government War Headquarters in the event of nuclear war.

Site Three – or 'Burlington Bunker' as it became known – was primed to receive Prime Minister Anthony Eden (pictured) as well as his entire Cabinet Office, along with civil servants and domestic support staff. All in all, the 'city' would have been able to house 4,000 people in complete isolation for three months.

Central Government War Headquarters, Corsham, UK

Jesse Alexander / Alamy Stock Photo

Over a kilometre in length with over 60 miles of underground roads, the site was blast-proof and held medical facilities, kitchens, canteens, offices, a map viewing room, a pub and the second largest telephone exchange in Britain, as well as living and sleeping quarters.

Drinking water was to be supplied from an underground lake and treatment plant, while fuel to power emergency generators was stored in 12 massive tanks. The bunker even contained a BBC TV studio, in case the Prime Minister needed to address the nation in a time of crisis, and a railway line that was to provide the royal family with an escape route straight from London.

Central Government War Headquarters, Corsham, UK

Jesse Alexander / Alamy Stock Photo

When the Cold War ended in 1991, the Ministry of Defense took over the site until it was decommissioned in 2004. Somewhat bizarrely, it was put up for sale the following year, for a reported £5 million (that would be around £8.6m/$10.8m today). However, whoever bought it would have had to invest in the military base that still operates on the ground above.

While the site had the potential to become a digital data store or even Europe's largest wine vault, it seems there weren't any takers and the bunker hit the market again in 2016 for £1.5 million (around £2m/$2.5m today). One prospective buyer was reportedly the 'doomsday realtor' Robert Vicino, who founded Vivos xPoint (more on that later), but once again the historic bunker failed to sell and its future remains unclear.

Tito's Bunker, Konjic, Bosnia Herzegovina

Ajdin Kamber / Shutterstock

Armijska Ratna Komanda D-0 is known to most as the ARK or – more simply – Tito's Bunker. In 1953, Yugoslav president Josep Broz Tito ordered building begin on the shelter, which was designed to protect the communist leader, his family and his political and military advisors from nuclear attack.

Built underground near the town of Konjic in what is now Bosnia Herzegovina, the shelter lies more than 900 feet below ground and consists of 12 connected blocks covering almost 70,000 square feet.

Tito's Bunker, Konjic, Bosnia Herzegovina

Jimmy Sime/Central Press / Hulton Archive / Getty Images

The atomic shelter was built for $4.6 billion (around £21.6bn/$27bn today) and it wasn't finished until 1979, one year before the death of Tito (pictured, left, with Winston Churchill in 1953).

With just three unassuming houses hiding the entrances to the site, at the time of its completion, only 16 people knew of its location. The workers who had built the bunker were blindfolded before being transported to the site each day and only allowed to remove them once inside. As a result, the bunker remained largely secret from the public until the 1990s and today, it is much the same as when it was first completed.

Tito's Bunker, Konjic, Bosnia Herzegovina

Fotokon / Shutterstock

Thanks to the bunker's deep underground location, blast doors and supplies of food, fuel and air, its 350 inhabitants could have theoretically survived for up to six months.

Consisting of more than 100 rooms, the labyrinthine complex contains conference rooms, offices and air filtration systems, as well as residential blocks, including the 'presidential block' reserved for Tito and his family.

Tito's Bunker, Konjic, Bosnia Herzegovina

Jasmin Brutus / Alamy Stock Photo

During the Bosnian War in the 1990s, the facility was scheduled to be destroyed to keep it from being captured by Bosnian fighters. However, the colonel charged with carrying out the demolition severed the wires that were supposed to detonate the explosives.

"Destroy everything you can't carry", was the order, according to Colonel Sherif Grabovica. "Despite the command, I could not destroy the place where I spent the best years of my life and destroy the efforts of several generations because of the command of insane leaders."

Tito's Bunker, Konjic, Bosnia Herzegovina

![<p>Zavičajac / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/0yVAng2NGcCOqz15iRHhCA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/e85199259a7ef8efd8b784bb376cdfd9)

Zavičajac / Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0]

While we don't know if Tito ever set foot in the bunker, he did visit an ammunition factory very close by, which is still in operation today.

In 2014, the abandoned bunker was declared a national heritage monument. Although it's still under the control of the Ministry of Defense, the fascinating space has hosted art exhibitions since 2011, intending to turn it into a regional cultural institution. It's currently open to the public for guided tours.

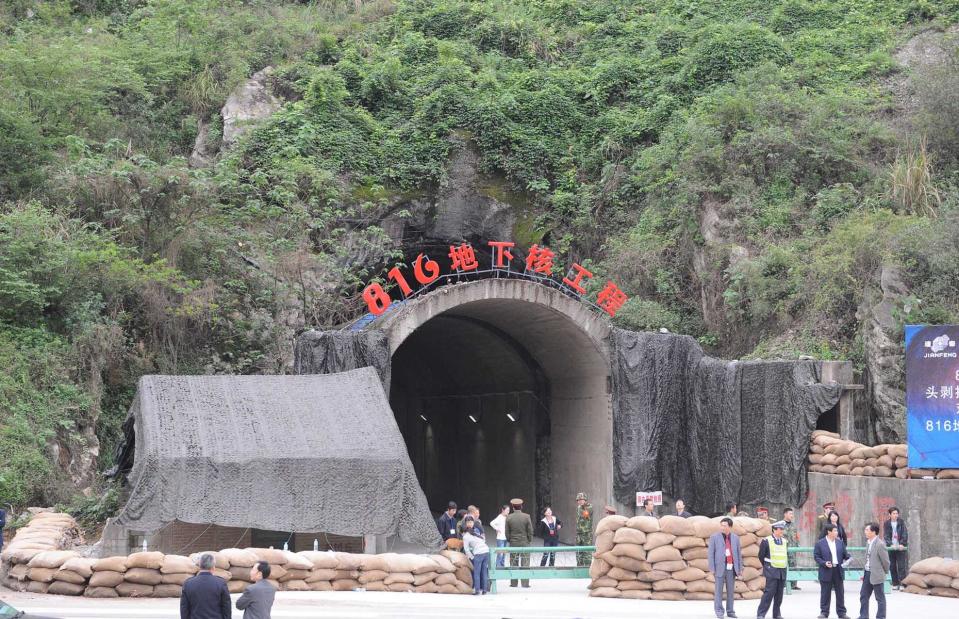

816 Nuclear Military Plant, Chongqing, China

Imaginechina Limited / Alamy Stock Photo

In the 1960s, relations between former communist allies China and the USSR deteriorated so much that another front developed in the Cold War. As a result, in 1966 China began building an enormous underground nuclear facility: 816 Nuclear Military Plant.

Around 60,000 special engineers were parachuted into the wooded mountains that stand above the Wu River in Chongqing and started excavating the land.

816 Nuclear Military Plant, Chongqing, China

Apic / Getty Images

Soldiers built what Chinese leader Mao Zedong (pictured) reportedly hoped would become their first nuclear reactor to produce weapons-grade plutonium.

The result was a one-million-square-foot bunker made up of 18 main caves and more than 130 roads, tunnels and shafts. Thought to be one of the world's largest man-made caves, 816 took 17 years to build.

816 Nuclear Military Plant, Chongqing, China

Imago / Alamy Stock Photo

Despite the enormous effort that went into building the bunker, the project was never finished and it closed before plutonium processing could take place there.

Inside, the air is cold and humid and the space, vast. The nuclear reaction hall is the largest cave in the complex. Its walls are almost 262 feet high and 82 feet wide and it covers 139,930 square feet.

Today, educational displays depict images of atomic clouds and plutonium processing, and tourists can have their photo taken next to a life-sized replica of an atomic bomb.

816 Nuclear Military Plant, Chongqing, China

WANG ZHAO / AFP via Getty Images

The caves are kitted out with modern sound and lighting systems. Areas of the facilities that would have been actively used in plutonium processing are lit in an eerie green light that wouldn't look out of place in a science fiction movie.

The soldiers who dug out the enormous caves worked in dangerous conditions, tunnelling into the rock with small drills, shovels and dynamite. It was a dangerous job, but workers were paid the equivalent of around £1 ($2.44) per month.

Officially the death toll stands at around 100, but even a tour guide who showed a New York Times journalist around the plant doesn't believe that figure. "The environment was too harsh," she said.

“Ultimately we worked on the project because we thought we were working for the nation," one former soldier revealed. He worked on the site from 1969 to 1974. "If we knew that in the end it would be made into a tourist site, we never would have participated.”

816 Nuclear Military Plant, Chongqing, China

WANG ZHAO / AFP via Getty Images

Work suddenly stopped on the plant in the early 1980s, and it was then used to produce chemical fertiliser. The site was declassified in 2002 and opened to the public in 2010.

In 2015, 816 closed for renovation work, before it reopened a year later adorned in neon accent lighting and newly welcoming foreign visitors as well as Chinese nationals. As the base never had the chance to store any nuclear material, visitors are assured that there's no need to worry about radiation on their three-hour tour.

Diefenbunker, Ottawa, Canada

The Canadian Press / Alamy Stock Photo

Hidden 75 feet under the village of Carp on the outskirts of Ottawa lies a 100,000-square-foot web of tunnels and rooms. This is the Diefenbunker.

Building began on the shelter in 1959 as a response to the heightened threat from a nuclear Russia and it was completed just 18 months later.

Spread over four levels, the complex is made from 32,000 cubic yards of concrete and 5,000 tonnes of steel. With a 387-foot blast tunnel and doors weighing several tonnes, the Diefenbunker was designed to withstand a five-megatonne nuclear explosion.

Diefenbunker, Ottawa, Canada

![<p>White House Photo Office / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/SMl8w0PHBEwuCtceADPFpA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/feb2e2583dc18db3eb7fa0cc1f25b697)

White House Photo Office / Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]

The Diefenbunker was named after John Diefenbaker, the then Prime Minister of Canada – pictured here, left, with Dwight Eisenhower in 1961. As far as the public was concerned, the Diefenbunker was a military communications base. However, in 1961 the Toronto Telegram newspaper revealed its true purpose as a fallout shelter for 565 of Canada's elite, including Diefenbaker, his family and his 12 most senior cabinet ministers.

The revelation – alongside the fact that Canada had very few public bomb shelters – sparked a national outrage so great that Diefenbaker vowed never to use the bunker. While never officially confirmed, the cost of the bunker was estimated to be around CA$22 million in 1959, which is about CA$220 million (£128/$163m) today.

Diefenbunker, Ottawa, Canada

The Canadian Press / Alamy Stock Photo

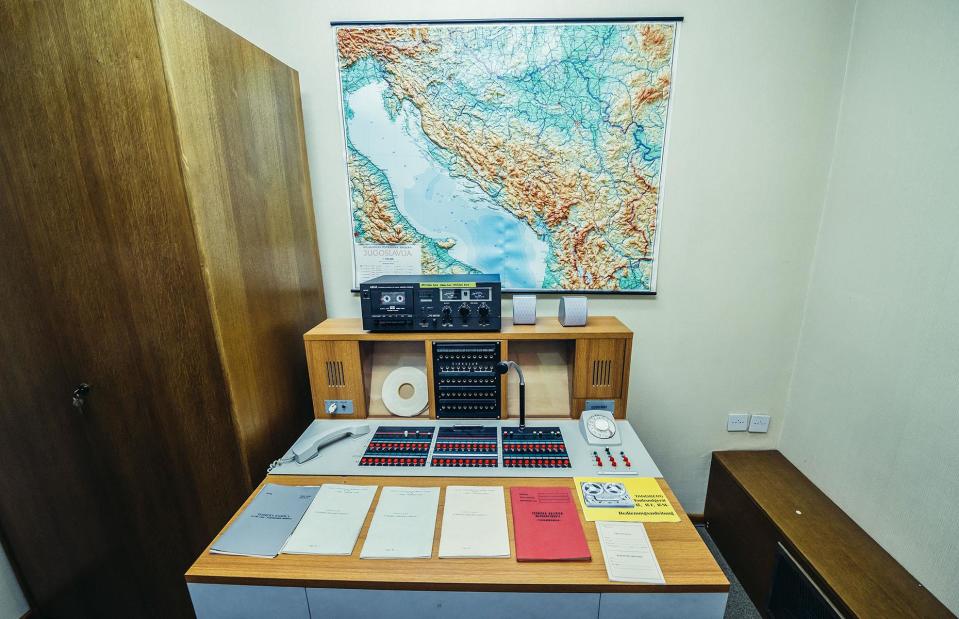

The subterranean shelter is made up of 350 rooms, including this radio room, which is kitted out just how it would have been back in the early 1960s.

The maze of tunnels also contained a Bank of Canada gold vault, decontamination showers, a CBC radio studio, a war cabinet room, a military briefing room and living quarters labelled for different cabinet leaders. The largest suite was reserved for the Prime Minister, although its only nod to luxury was a turquoise-coloured bathroom sink.

Diefenbunker, Ottawa, Canada

The Canadian Press / Alamy Stock Photo

The bunker even had an operating theatre, stocked with supplies and medicines as well as an early blood-testing machine.

After it was completed, the shelter remained operational for 32 years. During that time it served as a Canadian Forces Station, running 24 hours a day with a staff of up to 150 people. Until it was finally decommissioned in 1994, the bunker's storage rooms were kept fully stocked with enough fresh food and provisions to sustain 535 people for 30 days.

Diefenbunker, Ottawa, Canada

The Canadian Press / Alamy Stock Photo

After it closed, the Diefenbunker stood empty until it was turned into a museum in 1997. Today, curious tourists, history buffs and doomsday preppers alike can visit the facility most days of the year, with guided tours and free audio tours available.

A more popular attraction than ever, the bunker hosts escape rooms, artists in residence, educational exhibitions and week-long spy camps for children. Curious kids can even hold their very own birthday parties, 75 feet underground.

The Greenbrier, West Virginia, USA

Dynamic Photography / Shutterstock

The Greenbrier resort has stood among West Virginia's Allegheny Mountains since 1778. In the 19th century, its mineral springs lured elites from across the US, including politicians, diplomats and five sitting presidents.

During the Civil War, the hotel became a hospital and military command centre and again operated as a hospital during the Second World War before reopening in 1948. However, it wasn't the last time the resort served a military purpose. In 1959, the US Army Corps of Engineers began work on a top-secret underground bunker beneath the vast resort.

The Greenbrier, West Virginia, USA

Bettmann / Getty Images

President Dwight D. Eisenhower (pictured) had been a patient at Greenbrier when it was a hospital and he was a general in the Second World War. Later, during his time as president, tensions with Russia ramped up to a point that 'continuity of government' in the face of nuclear attack became paramount.

So, in 1959, building on a new conference centre commenced at the hotel – what ordinary citizens didn't know was that a 112,544-square-foot hideout was being built below it. It's here the US Congress would have relocated to in the event of war.

The Greenbrier, West Virginia, USA

![<p>Z22 / Wikipedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0]</p>](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/c7LcEcSCT61LHxzVRkkAQQ--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTYxOQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/loveproperty_uk_165/7995d3830e55e07c33c40d7d6ad32142)

Z22 / Wikipedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0]

Originally codenamed Project X, the Greenbrier bunker was also known as Project Caspar and later as Project Greek Island.

Buried 720 feet underground and capable of withstanding a nuclear detonation as close as 15-30 miles away, the two-storey refuge is protected from the outside world by enormous blast doors and 50,000 tonnes of concrete. The vast complex was completed on 16 October 1962, just one week before the onset of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

These doors, visible from inside the hotel, are secret access points into the bunker.

The Greenbrier, West Virginia, USA

Ian Patrick / Alamy Stock Photo

The secret bunker reportedly cost $14 million to build, which is the equivalent of around £116 million ($148m) today.

Inside, a 440-seat Governor's Hall was designed to hold meetings of Congress, while the 130-seat Mountaineer Room would have hosted the Senate. The largest room, Exhibit Hall, would have held joint sessions of the new subterranean government. The hotel has been using these to host conferences for unsuspecting guests ever since.

As well as offices for congressional leaders, the bunker held everything members would need to survive for six months, including a dentist's office, a hospital, an operating room, a pharmacy, a fully-stocked kitchen and a 400-seat cafeteria, decorated with false windows featuring bucolic views.

The Greenbrier, West Virginia, USA

Alex Wong / Getty Images

The politicians' sleeping quarters would have been quite a bit different from the bedrooms they were used to at home. There were 18 dormitories, each built to house 60 people in metal bunk beds.

While the bunker was supposed to be top secret, locals – and particularly the workers who built the shelter – soon guessed it was more than a hotel extension. “Nobody came out and said it was a bomb shelter, but…they weren’t building it to keep the rain off them," one construction worker told the Washington Post. "I mean a fool would have known.”

Vivos xPoint, South Dakota, USA

Vivos

Hailed as the 'largest survival community on earth', Vivos xPoint is a city of bunkers located near Edgemont, South Dakota. Originally named Fort Igloo, the 575 concrete and steel bunkers were built by the US Army in 1942. It was used as an ordnance depot until 1967, after which point the base was decommissioned and sold.

Billed by Vivos as "one of the safest areas of North America," the bunkers are positioned at an altitude of around 3,800 feet, far from large bodies of water and about 100 miles from potential military targets.

Vivos xPoint, South Dakota, USA

Vivos

Named after "the point in time when only the prepared will survive", xPoint is spread over an 18-square-mile area, that's three-quarters the size of Manhattan.

The bunkers are arranged over 100 miles of private road, with just one road in and out of the complex for increased security. Each shelter is buried beneath an elliptical bank of earth, designed to lessen the impact of a surface blast wave.

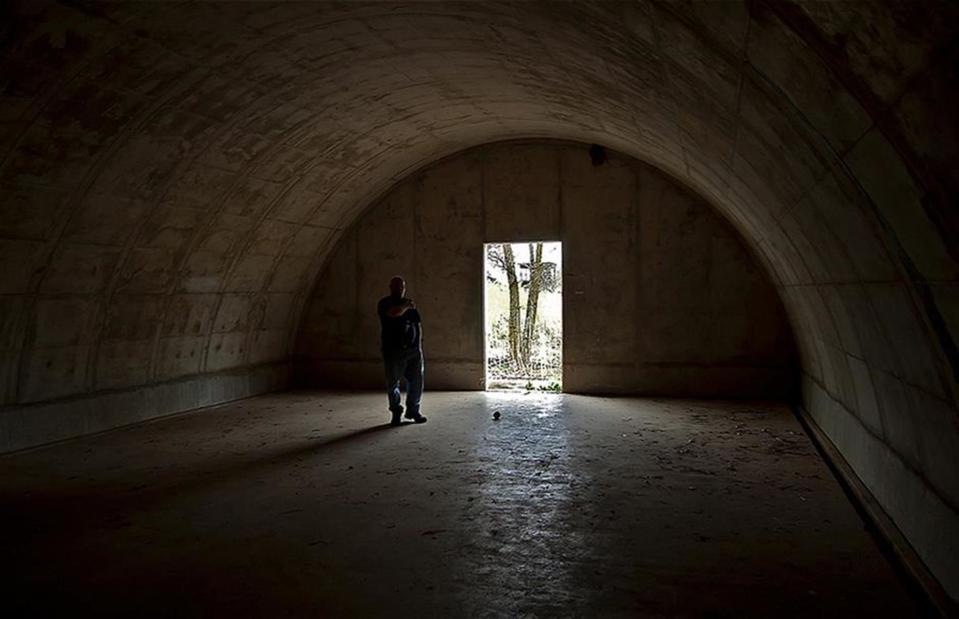

Vivos xPoint, South Dakota, USA

Vivos

Each shelter contains almost 2,200 square feet of floor space and can accommodate 10 to 24 people. At the highest point, the arched ceiling reaches 12.5 feet.

The bunkers' concrete and steel blast doors are designed to seal shut to stop any water, air or gas entering the space. There's a second exit should the main door become compromised. At full capacity, the site can house more than 5,000 "like-minded survivalists".

Vivos xPoint, South Dakota, USA

Vivos

Owners can create their own floorplans or choose from multiple different turnkey layouts. Fully outfitted bunkers can run to tens of thousands of dollars, or new residents can spend the minimum, doing up the space slowly over time.

Vivos has even designed a 'Bunker Glamping' kit, which enables owners to fit out their shelter for around £7,800 ($10,000), excluding the cost of a generator, composting toilet, water filter, lighting and paint.

Vivos xPoint, South Dakota, USA

Vivos

Currently, each bare bunker costs from around £43,000 ($55,000), in addition to an ongoing ground rent of £852 ($1,091).

According to Vivos CEO Robert Vicino, demand for bunkers spiked so dramatically during the pandemic that he earned over £780,000 ($1m) in just one day. More recently, Russia's invasion of Ukraine and its threat to use nuclear weapons has led to a dramatic increase in US bunker sales, according to The Guardian.

As well as xPoint, Vivos has an underground complex in Indiana and a luxury 227,904-square-foot bunker in Europe, as well as offering scalable bespoke bunkers that can be built anywhere in the world.

Oppidum L'Heritage, Global

Oppidum

For well-heeled survivalists, Oppidum L'Heritage is the perfect place to see out the end of the world. Covering 12,380 square feet and sunk 31 feet below ground, the luxury shelter can be built just about anywhere in the world – even below or right next to a multimillionaire's mansion.

Designed by French architect Marc Prigent, L'Heritage has all the opulent extras a wealthy prepper might expect.

Oppidum L'Heritage, Global

Oppidum

Constructed to last for centuries, the billionaire bunker is surrounded by thick layers of reinforced concrete, designed to protect inhabitants from nuclear blasts. It's gas-tight, energy-sufficient and kitted out with chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear protections.

It's also full of gadgets – such as this concealed hydraulically activated garage entrance. Inhabitants can also enter via a staircase from an optional helipad. From the garage – built to house multiple supercars – residents pass through two sets of custom-made blast doors, an airlock and a decontamination chamber before they reach the main living area.

Oppidum L'Heritage, Global

Oppidum

Inside, the opulent interior makes it easier for occupants to carry on their lives uninterrupted by events playing out on the surface.

This entrance hall is engineered to counteract the sense of being underground and decorated with hand-crafted glass chandeliers, custom-made furniture and solid wood flooring. Elsewhere, there's a dining area and lounge for relaxation, as well as a private meeting room that can be fully secured for privacy.

Oppidum L'Heritage, Global

Oppidum

The luxurious living quarters are a far cry from the government bunkers built during the Cold War. The lounge and bedrooms are securely separated from the rest of the shelter, allowing the inhabitants to draw a line between business and family life.

A suite of technical rooms hidden away from the main living areas sustains underground living. Two independent air filtration units, a carbon dioxide removal system and an auxiliary oxygen supply all combine to provide breathable air in case of an above-ground emergency.

Water is pumped into the residence from a private underground well, separate from the public water supply, while the power supply can switch between the grid, generators or backup batteries.

Oppidum L'Heritage, Global

Oppidum

Optional extras include a cinema, swimming pool, art gallery, gym, sauna and staff quarters to ease inhabitants through the end of days. They can also opt for an inner garden equipped with a skylight that provides a light spectrum simulation, including sunrises, sunsets and changes in season.

Unsurprisingly, these extravagant bespoke bunkers can take between three and five years to construct and cost upwards of £46.9 million ($60m).