When sharks attack: how safe are you in the water?

Cooling off in the turquoise waters of a tropical resort feels rather less appealing this Christmas in the wake of two fatal shark attacks in as many weeks. Newlywed Lauren Erickson Van Wart, 44, from Massachusetts, was killed while paddleboarding with her husband off the coast of Nassau on Monday, while in Mexico, a 26-year-old mother lost her life to a bull shark while swimming with her daughter, five, off Melaque Bay, Cihuatlán.

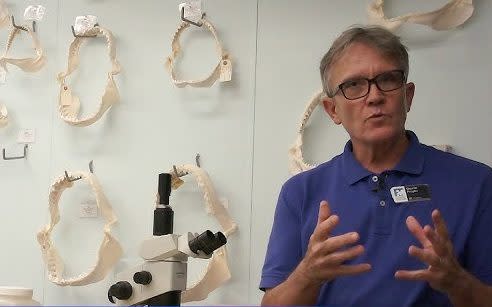

“It’s devastating that there have been two attacks in close succession in the run-up to Christmas,” says Dr Gregory Skomal, head of the Massachusetts Shark Research Program. “Shark attacks are always shocking: they’re brutal, they’re traumatic and at the end of the day it’s a person.”

Yet Dr Skomal and other marine biologists insist that it is no riskier swimming in the Bahamas or Mexico than in the past. The chances of being attacked by a shark stand at around one in four million (less likely than getting struck by lightning) and while there are more attacks now than in the 1960s, experts believe this is simply because there are more people in the water – fewer attacks recorded during the pandemic supports this view.

Each year, about 70 people across the globe are attacked by unprovoked sharks, with around five succumbing to their injuries, according to figures from the International Shark Attack File (ISAF), which has been recording attacks since 1958. Last year the figures were lower than average. “The numbers are on trend – there has been no rise in attacks,” confirms Prof Gavin Naylor, director of the Florida Program for Shark Research, which runs the ISAF.

Two fatalities in two weeks, though – could something be affecting sharks’ behaviour this winter? Prof Naylor concedes some factors can contribute to the likelihood of an attack: tour operators tipping bait into the water to attract sharks, for example.

“Sharks are readily habituated. They quickly come to expect food if it is put in the water at the same place,” he says. This is thought to be what caused three nurse sharks to bite nine-year-old British schoolboy, Finley Downer, in the Bahamas last year, when tourists threw their lunch into the water to entice sharks closer to their boat. He dismisses suggestions that sharks are drawn to paddleboards, surfboards and inflatables, though. “There are no environmental conditions that seem to account for the two recent bites,” he says.

There is evidence to suggest that sharks are on the move. Rising sea temperatures are driving them further north – to Northern California, for example – while humans are displacing the species from their natural habitats, forcing them into new areas. Prof Naylor does not believe this was a factor in these latest incidents, though. The fact remains that you’re very unlucky if you get attacked by a shark. “Many of us will have swum near sharks without realising,” says Prof Yannis Papastamatiou, a shark expert at Florida International University. “If we regularly got so close to terrestrial predators like mountain lions or bears there’d be attacks all the time.”

Of the 500-odd species of shark, it’s tiger sharks, great whites and bull sharks carrying out the majority of attacks but it’s not a given they’ll go for us. “We come low down the menu for them – even great whites prefer blubbery, oily prey like seals; we don’t taste good to them,” Prof Papastamatiou continues. The chances of being eaten alive by a shark are thus almost zero: sharks tend to bite once, twice if you’re unlucky and that will be it. They also tend to stick to one victim rather than savaging a whole group.

This doesn’t make the prospect of a dorsal fin weaving through the water towards you any less chilling though. Just one shark bite is often devastating, as sharks have five rows of teeth and will always bite as hard as they possibly can. “They ambush their prey using speed and stealth and they disable it as quickly as possible – it all happens in an instant,” explains Dr Skomal.

Lisa Monday experienced this in 2016 when she thought she’d been hit by a boat while wakeboarding in Australia and turned to find herself staring into the jaws of a 13ft-long great white. It bit her arm, severing four of the major nerves and damaging muscle and veins. Similarly, Mark Summerset, a surfer from South Carolina, was climbing back onto his board this August when he felt a block of teeth take hold of his face. He recalls a crunching sound and the water filling with blood – he was lucky to get away with 18 stitches.

No wonder, then, that humans consider sharks more terrifying than almost any other predator. Papastamatiou, who was inspired to study marine biology by Matt Hooper, the fictional oceanographer and shark enthusiast in Jaws (played by Richard Dreyfuss), puts our obsession with shark-related movies, stories and gory online content down to the fact we’re not evolved to fight in water. “Ocean-based predators are the most frightening because we’re not good in water: we can’t see what’s going on; there’s nowhere to hide; even the strongest swimmer is in trouble with a shark,” he says.

Personality wise, though, the great whites and tiger sharks he encounters on research dives are nothing like the one in Jaws. “It’s a great horror movie but, in real life, sharks aren’t actually as bloodthirsty as we’re led to believe,” he says – indeed, he regularly swims among them without any form of cage or protection. “People always want an explanation as to why a shark attack has occurred and for the most part it will be a case of mistaken identity – they think we’re something else, such as a seal,” he continues. Summerset, whose facial scars are a daily reminder of his ordeal, is 100 per cent certain that the shark attacking him was attracted by his necklace as they’re interested in shiny, light-reflecting objects.

Or it could be that the shark was being territorial: recently scientists have discovered that sharks identify stretches of water as their own. “If you come into their space, they’re going to defend it,” explains Dr Skomal. “And if you provoke them, which is what we do when we’re tagging them, you can expect them to get defensive.”

He blames himself for nearly being bitten a number of times when studying their behaviour. “I was putting a tag on a bull shark in the Bahamas and it suddenly lunged at my legs,” he explains. Papastamatiou had one of his flippers bitten off by a shark when diving at night. “I suddenly found myself caught up in a feeding frenzy. I started to reverse away when I felt one bite down on my flipper,” he says. Now he takes a piece of PVC pipe with him when he dives – not to hit the shark with, he insists, but to give it something else to bite.

No one wants to get into a fight with a shark. Yet if you find yourself staring at their tonsils, you have to try to save yourself; the ISAF suggests punching it on the nose. “Good luck with that,” Papastamatiou says. “You won’t know what’s going on, so you need to strike it anywhere you can and hope you get somewhere sensitive like the nose, eyes or gills.” If it hasn’t attacked you yet, don’t turn away or it will chase you; keep your eyes glued to it, he advises, and try to reverse calmly. “If it does bite, hopefully it will get your extremities, which are more dispensable than parts of your body where vital organs are located.”

Papastamatiou admits he feels vulnerable when he dives with sharks, yet there is something awe inspiring about being close to such powerful creatures, he says. It’s the same sense of wonder that inspired Dr Skomal’s book, Chasing Shadows, about his life spent tracking great whites. “I’m not saying I’m a shark hugger but there’s a reason why people pay so much to swim with sharks,” he says. “They’re beautiful and they’re majestic and they fulfil a role that is critical in the ecosystem.”

Plus, from a research perspective, one has to get close to them in order to tag them, which is the best way of learning more about the species. “We’ve discovered so much about them over the past decade,” Papastamatiou agrees. “They’re much more complex than we ever thought possible.”

Indeed, recent research shows that sharks are sociable, forming close bonds with other sharks, and they travel vast distances, reaching depths of more than 3,000 metres. “What we still don’t know is what they do down there,” Dr Skomal continues. “The more we learn about them, the more questions we have.”

One of the biggest mysteries, he says, is we don’t have killer sharks off the coast of Britain. The water is an ideal temperature for them and there is plenty to eat; they travel across the equator and yet don’t cross the Atlantic to Britain. “There’s nothing in history to suggest they ever have,” he says. “It might be something that happens in the future – anything is possible.”

This isn’t what those with active imaginations want to hear, although as Papastamatiou says, the only way one can ever be certain there isn’t a shark lurking beneath, is to swim in a pool.