See inside the ancient temples of the Americas

Treasures of the ancients

N. Rotteveel/Alamy

The Aztec, Incan and Mayan empires left behind magnificent ruins across Mexico, Central and South America, which today provide most of what we know about these fascinating and mysterious civilisations.

Read on to see inside America's ancient pyramids and temples. From jade death masks to towers of human skulls, discover the treasures and horrors found within...

El Castillo, Chichen Itza, Mexico

Fer Gregory/Shutterstock

Mexico is dotted with incredible ancient Mayan sites, including the renowned Chichen Itza. The political and economic hub of Mayan civilisation between AD 750 and 1100, the extensive ruins offer a unique window into this mysterious people, most notably their astounding astronomical and mathematical skills. Chichen Itza's best-known structure is El Castillo (or Temple of Kukulcan), believed to have been built around AD 1000.

El Castillo, Chichen Itza, Mexico

Dan Herrick/Alamy

During restoration work in the 1930s, archaeologists dug into El Castillo's south side and came across the remains of an older pyramid hidden within. They followed the staircase upwards thinking they'd reach the older temple's peak, but instead came across a chamber in which they found a well-preserved chac mool (pictured), a Mayan sacrificial stone sculpture.

El Castillo, Chichen Itza, Mexico

User:HJPD/Wikimedia/CC BY-SA 3.0

The discoveries didn't end there, and continued excavation revealed a second chamber just behind the first, which contained this red jaguar throne. Jade was used for the eyes and green spots while the fangs were made of flint, probably positioning it in the Classic period (AD 200-900). The striking sculpture may have been used as a throne for the high priest.

Feathered Serpent Pyramid, Teotihuacan, Mexico

Andreas Wolochow/Shutterstock

Literally translated as 'the place where the gods were created', the pre-Columbian complex at Teotihuacan is the second most visited archaeological site in Mexico behind Chichen Itza. With its ruined palaces and grand pyramids, the sprawling ancient city rises majestically from a vast plain, though we still know remarkably little about who built it, or when and why it was built. Despite its mysterious origins, the site, just to the northeast of Mexico City, is thought to have had a strong influence on the latter-day Aztecs.

Feathered Serpent Pyramid, Teotihuacan, Mexico

Ronaldo Schemidt/AFP via Getty Images

In 2003, excavations at the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent (also known as the Temple of Quetzalcoatl) wowed the world. The archaeological team uncovered a tunnel (pictured) which had lain undisturbed for 1,800 years. Inside the sealed-off passage were ritual offerings to the gods, including four greenstone statues, hundreds of metal spheres and beetle wings arranged in a box. They even found tiny lakes of liquid mercury – perhaps meant to resemble the underworld.

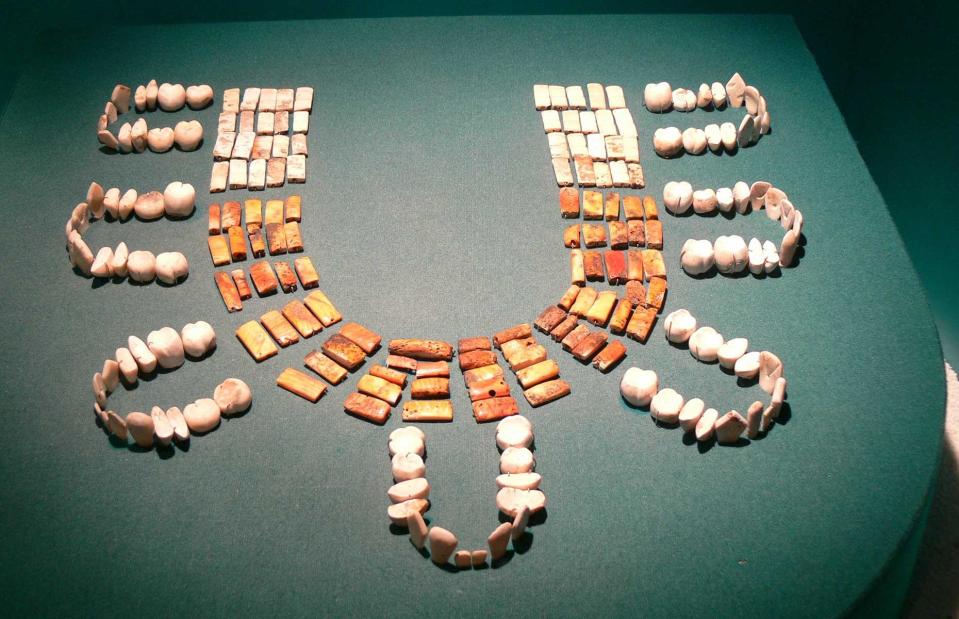

Feathered Serpent Pyramid, Teotihuacan, Mexico

Wolfgang Sauber/Wikimedia/CC BY-SA 3.0

In past decades, archaeologists at Teotihuacan have found evidence of human sacrifice inside the pyramid. Up to a hundred bound warriors, many wearing tooth-like or actual tooth necklaces like the one pictured here, are now believed to have died there.

Great Pyramid of Cholula, Puebla, Mexico

Diego Grandi/Shutterstock

Larger than the Great Pyramid of Giza (with almost twice its volume), the Great Pyramid of Cholula is the largest pyramid to survive into the modern age – and is even larger than those in Egypt. Construction began on the building around 200 BC, and the design was perhaps intended to mirror the majestic Popocatepetl volcano that sits nearby. At 1,476 feet wide (450m) and 216 feet tall (66m), the epic building was almost completely overgrown by the time the Spanish arrived, and parts of the pyramid are still obscured by grass and soil.

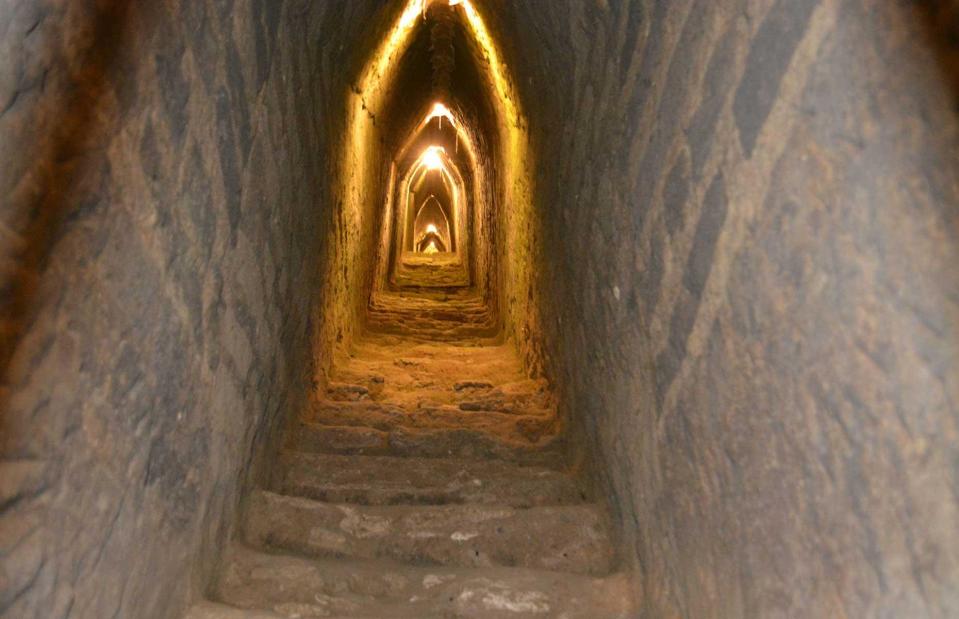

Great Pyramid of Cholula, Puebla, Mexico

Sicaru/Alamy

Excavations have revealed a tantalising network of passageways totalling five miles (8km) in length. Archaeologists discovered seashells, altars, ceremonial figurines and the burial places of unfortunate human sacrifices, which, rather gruesomely, yielded the deformed skulls of two decapitated children.

Great Pyramid of Cholula, Puebla, Mexico

Jay Galvin/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

In 1969, archaeologists accidentally discovered this mural called 'los bebedores' (the drinkers) at a depth of 25 feet (7.5m). Some 1,800 years old, the merry scene depicts drunken revelry at a pre-Hispanic ceremony, probably dedicated to the goddess Mayahuel. Deep within the pyramid and hidden from public view, the 200-foot (60m) mural briefly went on display for the first time in 2014.

Pyramid of the Niches, El Tajin, Mexico

Leonid Andronov/Shutterstock

El Tajin was a pre-Hispanic city, inhabited roughly between AD 600 and 1200, which temporarily became the most powerful city in Mesoamerica after the fall of the Teotihuacan Empire. While the site hasn’t been fully excavated, one of the best-known structures is the Pyramid of the Niches. Its tiers contain 365 symmetrically-arranged little nooks – representing each day in the solar calendar – which may once have contained offerings to the gods.

Pyramid of the Niches, El Tajin, Mexico

Richard Ellis/Alamy

El Tajin is also well-known for its elaborate carved stone friezes and panels. Pictured here is a particularly well-preserved section that once supported a portico beneath two pyramidal structures.

Pyramid of the Niches, El Tajin, Mexico

AlejandroLinaresGarcia/Wikimedia/CC BY-SA 4.0

The carved stones also adorned the walls of El Tajin's ball courts (the site had 17 that we know of, more than any other known site of this size), and mostly depicted narrative scenes. Pictured here is a tablet purported to depict a ball-player being beheaded – supposedly a punishment for losing the game. It’s even been speculated that the heads were used as balls...

Chan Chan, Peru

Myriam B/Shutterstock

Chan Chan, on the northern coast of Peru, was the largest city in pre-Columbian South America during its heyday. The adobe city was divided into nine ‘citadels’ or ‘palaces’, each with pyramidal temples and funerary platforms enclosed with thick, earthen walls. Once the capital of the Chimu Empire (AD 900-1470), the site's poor state of repair means that today you'll find it on UNESCO’s list of World Heritage Sites in danger.

Chan Chan, Peru

CRIS BOURONCLE/AFP via Getty Images

In 2018, some 19 wooden sculptures were discovered along an adobe corridor wall. Each was made from wood with masks made from clay, while some held a sceptre (staff) in one hand and possibly a shield in the other. Roughly 70cm high, the statues were buried over 750 years ago, along with a 20th sculpture that has unfortunately long been destroyed.

Chan Chan, Peru

Courtesy of Roger Guerrero Bazalar/Proyecto Especial Complejo Arqueológico Chan Chan

Then, in July 2022, another wooden sculpture was unearthed. At 47cm tall, this colourful relic depicts a royal litter-bearer with a flat red-painted face and prominent nose. Wearing a cap and triangular-cut skirt, its form and art style roughly date it to between 850 and 1,470 years ago, making it one of the oldest sculptures found at the site.

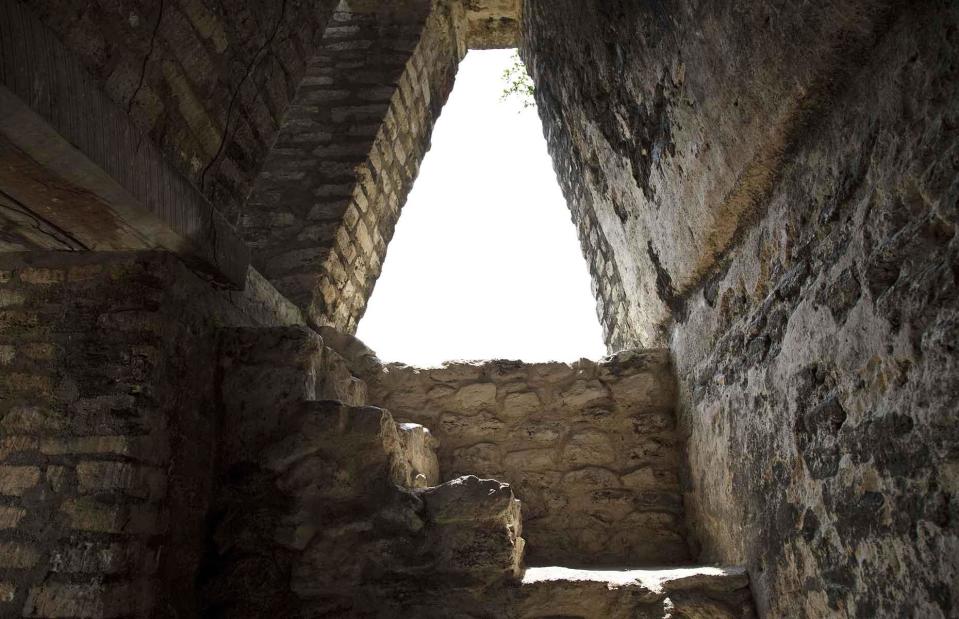

Xunantunich, Belize

milosk50/Shutterstock

One of Belize's top tourist attractions, Xunantunich (‘stone maiden’ in the Mayan language) sits on a levelled hilltop near the Guatemalan border. The ancient city flourished between AD 700 and 1000 – a pretty short period of prosperity compared to its contemporaries. There are several important structures at the site but the stand-out is El Castillo, previously a temple, residence and hub for the administrative elite.

Xunantunich, Belize

milosk50/Shutterstock

In 2016, archaeologists uncovered a royal tomb 16-24 feet (4.8-7.3m) beneath the ruins – one of the largest burial chambers ever found in Belize. Inside, the team found a skeleton buried with jaguar and deer bones, six jade beads and an assortment of blades and ceramic vessels. Though long thought to be male, recent DNA analysis has revealed that the skeleton inside was in fact a woman.

Xunantunich, Belize

Photograph by Christophe Helmke, reproduced with permission of the BVAR project

Hieroglyphic panels also found in the tomb depict the history of the ‘snake dynasty’, a ruling family dating from the 7th century AD. One section, dated to 2 December, AD 638, mentions the death of Lady Batz’ Ek’, the mother of Lord K’an II who ruled neighbouring Caracol. It’s thought that after Caracol was defeated in battle years later, the panels were dismantled and reassembled elsewhere. Experts are unsure exactly how or why the panels appeared at Xunantunich. Who doesn’t love an unsolved mystery?

Templo Mayor, Tenochtitlan, Mexico

WitR/Shutterstock

Founded in 1325, Tenochtitlan (not to be confused with the aforementioned Teotihuacan) was the capital of the Aztec Empire. Templo Mayor was its crown jewel. During the Spanish conquest of 1521 the temple was destroyed and replaced with a Christian cathedral, but little did anyone know that beneath the structure were at least six earlier versions of the Templo Mayor; each built on top of the previous one for successive rulers.

Templo Mayor, Tenochtitlan, Mexico

miguelão/Wikimedia/CC BY-SA 2.0

This large stone relief of Coyolxauhqui (an Aztec goddess) found at the site weighs eight tonnes and was likely carved in the 15th century. Other discoveries include incense burners, vessels containing cremated remains and Huey Tzompantli: a terrifying tower of more than 600 human skulls, including those of children. It is thought that there are six more of these fearsome structures in Tenochtitlan…

House of the Eagles, Tenochtitlan, Mexico

Ronaldo Schemidt/AFP via Getty Images

Immediately beside Templo Mayor lies the smaller House of the Eagles, once a meeting place for the fearsome eagle and jaguar warriors, the two most important ranks in the Aztec military. Two extraordinary figures were excavated here; the eagle warrior in this image stood in the doorway, serving as a guardian figure, and was once brightly painted and covered in feathers.

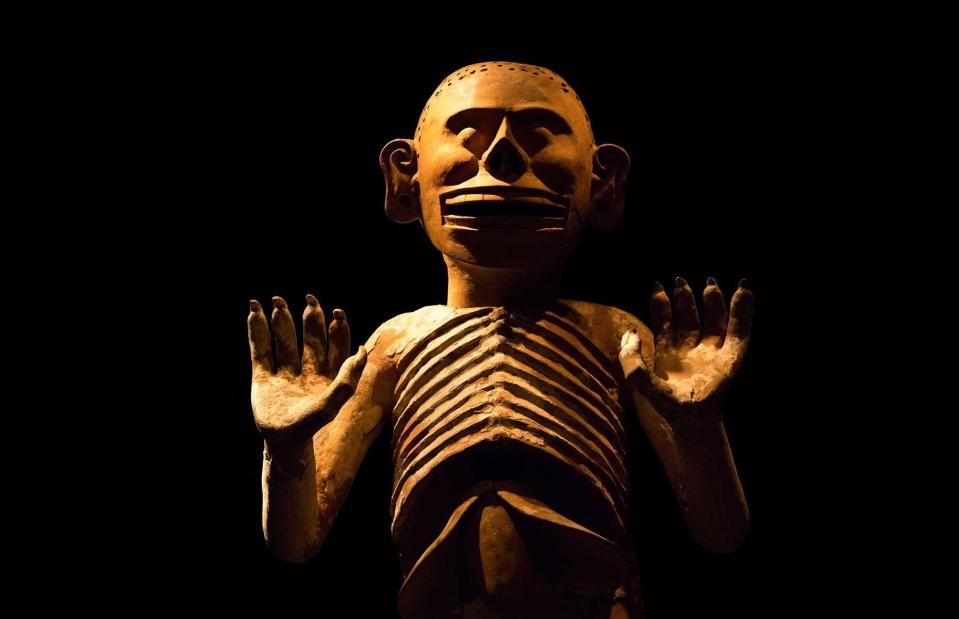

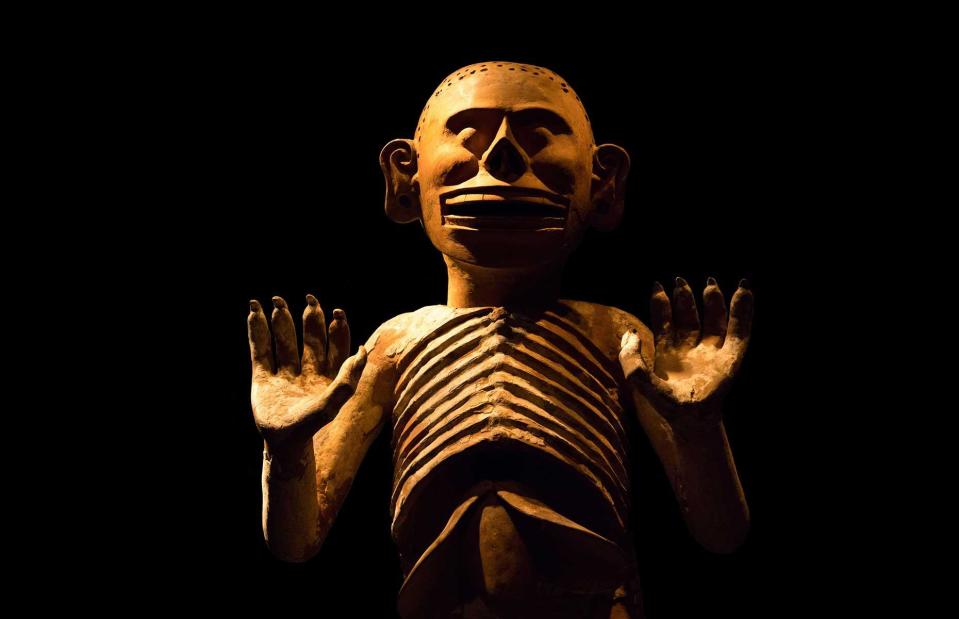

House of the Eagles, Tenochtitlan, Mexico

N. Rotteveel/Alamy

At a second doorway stood this six-foot (1.8m) statue of Mictlantecutli, the god of the underworld, who would have had hair or paper decorations fixed onto his head. An intimidating figure, his lipless mouth is fixed in a pained grimace, while his exposed ribcage and raised, clawed hands would be enough to frighten any interloper.

Caracol, Belize

velvetweb/Shutterstock

Known as Uxwitza ('three water hill') to its Mayan inhabitants, Caracol (Spanish for snail shell) was renamed after the curving road that leads up to the site. A crucial centre of Mayan power, at its height Caracol was significantly more populous than any modern Belizean city, and covered a much larger area than current capital Belmopan. The Caracol royal dynasty was founded in AD 331 and the city was at its strongest between AD 550 and 900, but was mysteriously abandoned in 1050 before being gradually reclaimed by the jungle.

Caracol, Belize

Danita Delimont/Alamy

Caana ('sky place', pictured) is the most famous building here, with four palaces and three temples. Its name is still fitting centuries later – at 141 feet (42m) high, it remains the tallest building in Belize. Hundreds of royal and non-elite tombs have been discovered around the site over decades of excavations, with some yielding painted texts and hieroglyphics. One remarkably intact tomb dating to AD 634 belonged to a royal female, who was buried with jade items including earrings and other jewellery.

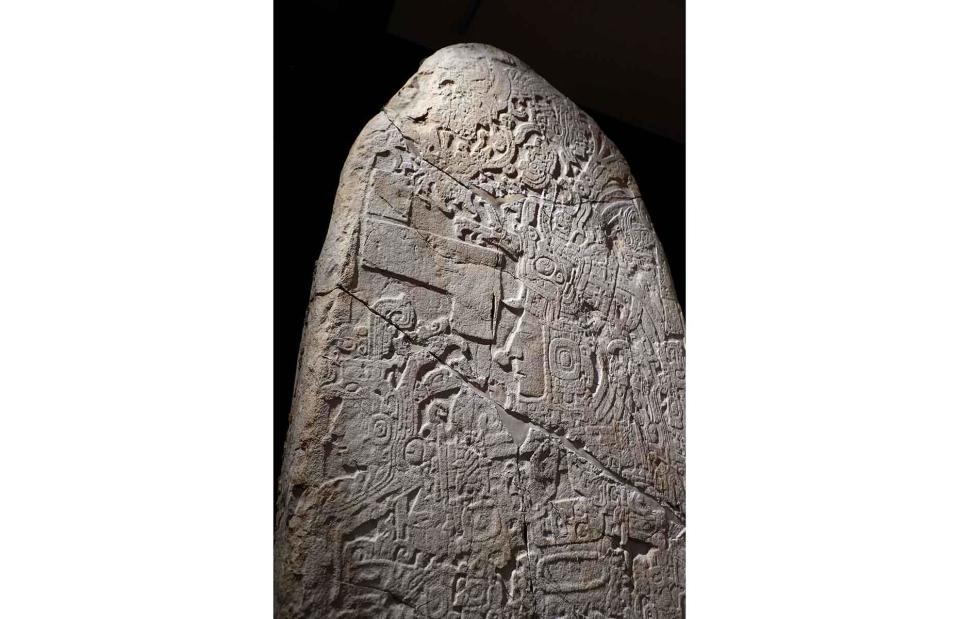

Caracol, Belize

CNMages/Alamy

There’s also a hoard of carved stelae (inscribed stone slabs) strewn across the site. These ‘tree stones’ depict stories from Mayan culture, ranging from royal life to warfare. The last recorded date found on these mighty stones is 22 January, AD 859.

Tikal, Guatemala

Simon Dannhauer/Shutterstock

Hidden in the depths of the Peten rainforest, the legendary pyramids of Tikal were built between AD 300 and 900. The ancient Mayan city was then known as Yax Mutal, and was among the most powerful kingdoms ever to exist in Mesoamerica. Among the 4,000 structures found here are six magnificent temples, as well as plazas and pyramids plus copious Mayan art and hieroglyphics.

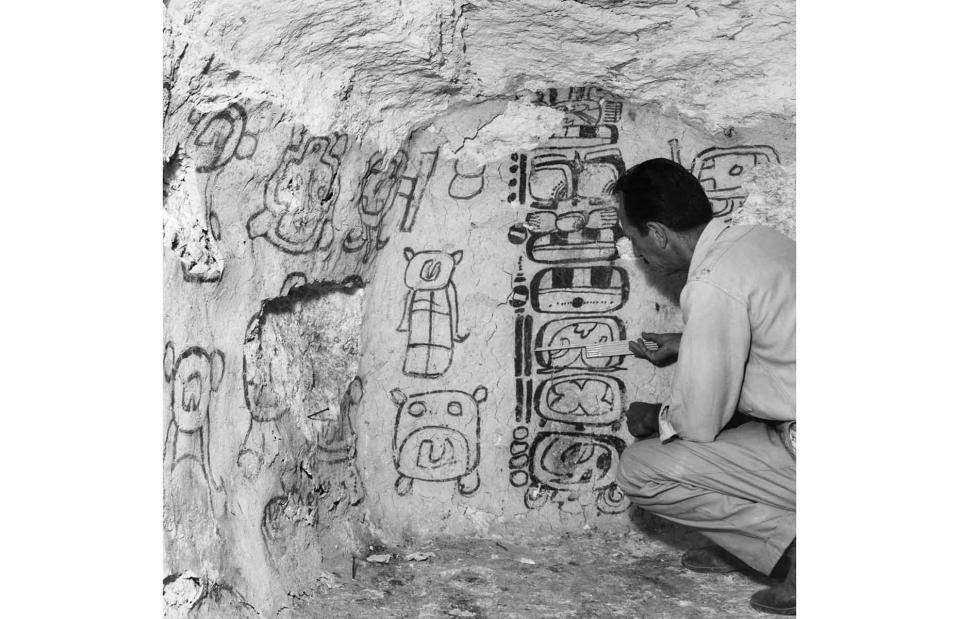

Tikal, Guatemala

GRANGER - Historical Picture Archive/Alamy

Taken in 1961, this image shows archaeologist Aubrey Trik inside 'the Painted Tomb' in Tikal's North Acropolis. The painted glyphs he's examining record a date of 9.1.1.10.10. in the Mayan calendar, which corresponds to 18 March, AD 457. The larger glyphs either side of the date are more mysterious, and probably refer to people or places.

Tikal, Guatemala

Photo by Pictorial Parade/Getty Images

Two teenage skeletons and a headless male skeleton (almost certainly sacrificial victims) were found inside the Painted Tomb, alongside rich offerings like this polished black vessel with carved and incised design panels. Other beautiful vessels found here feature bird-themed designs with modelled heads for handles and painted stucco (a type of plastering). Some were carefully wrapped with cotton cloth.

Temple of the Inscriptions, Palenque, Mexico

Jess Kraft/Shutterstock

One of the best-known monuments in the Mayan world and among the largest of the Mesoamerican stepped pyramids, the Temple of the Inscriptions ('House of the Nine Sharpened Spears' in the original Mayan) sits atop a 65-foot-high (19m), nine-tier pyramid. It gets its modern name from its inner temple walls, which are covered with a patchwork of carved inscriptions. The colossal complex lies in the ancient city of Palenque, which the Mayans knew as Lakamha ('Big Waters').

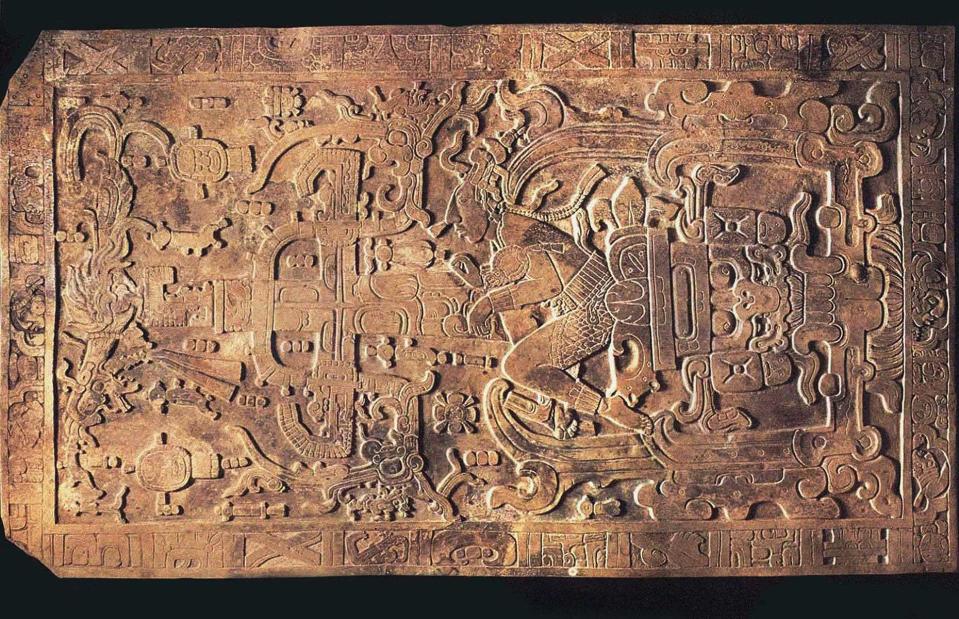

Temple of the Inscriptions, Palenque, Mexico

Album/Alamy

Deep inside the temple was King Pakal’s funeral chamber. The Mayan ruler of Palenque was 12 years old when he came to power and reigned for a then-unprecedented 68 years. He was buried here in AD 683 but, interestingly, his mighty sarcophagus was wider than the passageway to his chamber, suggesting that the temple may have been built up around his tomb. The stone coffin lid (pictured) was a single slab with carvings depicting Pakal en route to the underworld.

Temple of the Inscriptions, Palenque, Mexico

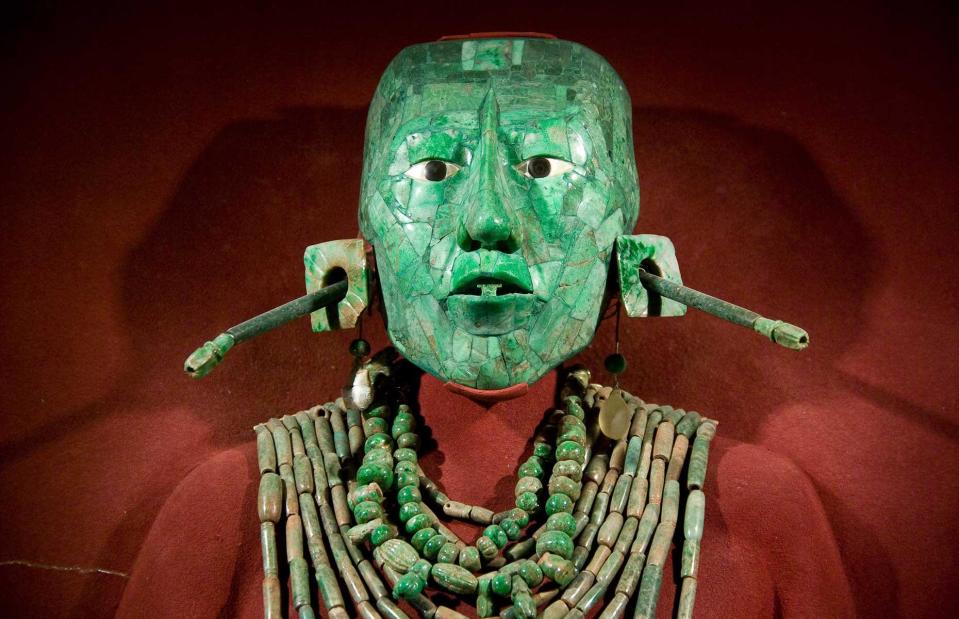

J.Enrique Molina/Alamy

The most incredible discoveries were found inside his coffin – best of all this unforgettable death mask made of jade, surely one of the most striking pieces ever unearthed in Central America. The deceased king symbolically held a small cube in one hand and a sphere in the other. Some believe that during the winter solstice, a small slit in the temple allowed sunlight to shine directly onto his coffin.

Now discover what the inside of Egypt's pyramids really looked like