How safe is Orlando for LGBTQ people in ‘Don’t Say Gay’ Florida?

Florida: the state where many Americans and expats from this side of the pond traditionally spend their old age under the ever-bright sun. For a long time, the Sunshine State was a small paradise where nothing ever went wrong. A place where the retired drifted from golf course to cruise ship. But those days are numbered: nowhere in the United States has social division become as pronounced as in Florida. When did the Floridians lose their vision?

The deeply divided United States has been showing a consistent pattern for years. Liberal and open-minded individuals mostly reside in large cities, often in the West or East of America. These areas are referred to as blue — Democrat. The conservative minority lives in the red — Republican-voting — areas, typically found in the middle of the US. Florida is an exception.

The state is dark red but for a number of dark-blue pockets including Miami, Fort Lauderdale, Tampa, and Orlando. In the latter, even the city government is notably queer-friendly. However, drive out of the city for half an hour, you’ll stumble upon the trigger-happy and narrow-minded, for whom drag queens belong in a special place in hell.

The aversion that conservatives feel towards (among other things) queer people is fuelled by two Florida residents: the former president Donald Trump and Ron DeSantis. Last year, DeSantis was re-elected as governor for a four-year term. Only during the midterm elections in 2026 can Florida elect a new incumbent. ‘Meatball Ron’, as Trump likes to call him, has caused significant damage since taking office. He’s cut almost all subsidies for queer organisations and introduced laws aimed at harming the LGBTQ+ community.

These included criminalising the provision of gender-affirming care to minors, restricting drag performances, and allowing healthcare providers to refuse patients care based on religious, moral or ethical grounds. But his most notorious action is undoubtedly the Parental Rights in Education bill, the “Don’t Say Gay” law, which criminalises the “promotion” of a queer life in schools, in a similar way to Russia’s “gay propaganda” law.

Mickey and Donald (the duck) speak out

Florida is famously the home of Disney. It is an economically significant company in Florida, with more than 35,000 people visiting Walt Disney World in Orlando — “the happiest place on Earth” — every day. As a powerful entity in the state, Disney voiced its opposition to the “Don’t Say Gay” law. It has reaped the consequences.

Since the 1960s, the entertainment giant gradually took on more responsibilities and privileges in the Reedy Creek Improvement District area where its parks are located. It was self-governed by five Disney supervisors who oversaw road maintenance and regulated safety inspections — it even had its own fire department. The company enjoyed some tax benefits as a result. But in retaliation for Disney’s opposition to his “Don’t Say Gay” law, DeSantis directed his anger at Reedy Creek, signing a bill to effectively dissolve the district from June 2023.

It has now been renamed the Central Florida Tourism Oversight District and is governed by five DeSantis-appointed board members. But Disney fought back, intervening before power changed hands and signing new contracts for the majority of its activities. DeSantis was left empty-handed. He is now trying to assert his authority through the legal system to have the contracts nullified. Meanwhile, Disney has filed counterclaims to have the agreements declared valid and enforceable.

Disney is also suing DeSantis and his officials in the federal court. They allege that DeSantis violated its free speech rights by punishing the company with the above actions.

Needless to say, DeSantis isn’t popular with the state’s rainbow families. Many queer residents have turned their backs on the state. The changes in Florida are having a wider effect too.

In April of this year, Equality Florida, a civil rights organisation dedicated to full equality for the LGBTQ+ community in the state, issued a travel warning: do not come to Florida. This was the result of changes to gun legislation and the numerous laws hostile to the LGBTQ+ community, including those that restrict access to reproductive healthcare. As a result, Florida has seen the number of LGBTQ+ visitors fall by 20 to 30 per cent this summer.

Founded by Chris Manley in 1991, GayDays Orlando is an annual event where rainbow families visit Disney World’s Magic Kingdom in red attire on the first Saturday of June.

The current CEO of GayDays, Joseph Clark, tells me Manley’s story. “He wanted visibility for the queer visitors of Disney and, therefore, he and some friends wore the same colour shirt. Every year, more people joined, and now GayDays is a massive gathering of people who want to be seen.”

Every year, Clark books the entire DoubleTree hotel as the home of GayDays — that’s 1,054 rooms. Not nearly enough, of course, because until recently, 180,000 people attended GayDays. “GayDays is a big party, but what makes us unique is that there are so many different things to experience — it’s not an everyday circuit party. In the days before and after the first Saturday in June, there’s a travel and business conference, drag queen contests, leatherman contests, porn-star bingo, AA meetings, and childcare is arranged for the daddies.”

The event’s “shameless pool parties” are another draw, according to Clark. “There are two pools at the DoubleTree hotel: one is a bear pool, it’s often busier than the other pool. On Sunday evening, we rent out the Aquatica water park across from the hotel. Aquatica is 140,000 square metres — equivalent to 28 football fields. Guests buy tickets for all events from us. We’re independent: Disney is not a sponsor and is not directly involved in GayDays. Once a year, we bring a lot of visitors. You’re welcome, Disney!”

But last June there were fewer visitors attending GayDays than before the Covid pandemic. Clark believes all the trouble in Florida is at the root of this. “People just say it: ‘We don’t feel safe here,’” says Clark. “And not just Americans, international guests react the same way. They no longer feel welcome here.”

Pride in… October

In Orlando, Pride does not take place in June. Tatiana Quiroga, executive director of Come Out with Pride, explains why. “Our festival takes place in October, around National Coming Out Day. We chose not to celebrate Pride in June like many other cities do. This decision has to do with our climate: it’s very hot in Orlando in June. Besides, October is LGBTQ+ History Month in Orlando. We’re not alone in this — Prides in Florida are spread throughout the year; there are also Prides in February and September.”

Come Out with Pride was founded in 2004 and only became fully independent as an organisation in 2021. The festival is a one-day event that takes place on a Saturday in October around Lake Eola Park in downtown Orlando. Quiroga says, “On that day, we take over the entire park, as well as the streets around it. It’s the largest daytime event in the city: last year, there were 200,000 visitors. On both sides of Lake Eola, we have two stages where we present ourselves. Come Out with Pride is a true family event while standing side by side with the drag community.

“Of course, we collaborate with many other organisations, such as Zebra, which focuses on providing support for homeless youth. As a Pride event, we welcome all groups within our community. Even Disney actors participate in our parade, but the Disney organisation itself doesn’t. Mind you, not too long ago, people asked us to exclude Disney from Pride because Disney was supporting DeSantis back then. How things change.”

The hostile political environment in Florida is affecting this event, too. When I speak to Quiroga before it takes place, some well-known transgender individuals have spoken out online, advising people not to attend Come Out with Pride due to safety concerns. Quiroga is quite annoyed by this.

“We have started a task force for trans and non-binary individuals, and our board includes four transgender persons. They are real leaders in our community — outspoken individuals,” Quiroga says. “In March, we organise a ‘trans march’, and this year, we’re even celebrating Trans Pride as part of our Pride because we truly want to be inclusive. So, I’m a bit surprised. The hesitation has nothing to do with Come Out with Pride but everything to do with Governor DeSantis.”

Quiroga stresses how important it is that people support Come Out with Pride by attending, “Even though the political situation in our state is unstable, we won’t change our Pride programme. Other Prides this year have been cancelled at times or have suddenly become restricted to ages 18 and older. We’re not doing that. If you don’t come and don’t make your voice heard, you’re letting yourself be silenced a little.”

In the end, this year’s Come Out with Pride event was well supported, with more than 200,000 attending. Sadly, this isn’t the case for all LGBTQ+ events. As Quiroga indicates, DeSantis’s laws have led to a forced self-censorship for other Prides across Florida, leading to them being cancelled, sponsors pulling out and age limits imposed. Although this year’s annual Tampa Pride festival went ahead on 25 March, organisers took the decision to cancel its Pride on the River celebration after sponsors expressed concerns over the outdoor setting. Meanwhile, Pridefest in Port St. Lucie, located 110 miles off Miami, cancelled its parade and restricted other events to adults aged over 21.

“We hope that everyone understands that this is definitely not what we wanted at all, and we are working with the city to assure our safety as well as produce a positive event,” stated its organisers the Pride Alliance of the Treasure Coast in a Facebook post.

Telehealth and grab & go condoms

Lake Eola Park is situated in the heart of downtown Orlando. The city is a sprawling area with many lakes. It seems like the neighbourhoods around the lakes were built and gradually grew towards each other. In downtown, Church Street is the central street with the most activity. An official queer neighbourhood isn’t easily pinpointed in this city.

Residents say that “all of Orlando is queer enough”. However, North Mills Avenue, located slightly north in downtown, has historically been an area with a lot of queer life and still has a significant number of, often older, LGBTQ+ residents. It is also home to The Center, an organisation which has been providing assistance to the LGBTQ+ community for 45 years.

George Wallace is its chief executive officer. “At The Center, we offer mental healthcare — including for survivors of the Pulse nightclub shooting,” he says. “We distribute grab-and-go condoms, manage our Pride Pantry — a food bank for LGBTQ+ individuals — host activities for our youth group, our elder group, and a special programme for transgender individuals. Oh, I almost forgot the HIV and hepatitis tests: there are four locations and a mobile testing centre. In America, hospitals hardly manage case management for HIV patients. It’s almost always outsourced through the Ryan White programme. So, we take on these projects. The medical aspect is done in hospitals or one of the many health centres. They also distribute PrEP. It’s free and accessible in America.”

Mental health is a significant part of The Center’s work. They have seven counsellors, and yet there’s still a two-month waiting list. During Covid, The Center mainly provided assistance over the phone. Now, people also have the option of coming in for a face-to-face appointment. Since there are already so many specialised youth support organisations, like Zebra across the street, which they collaborate with, The Center’s counsellors receive requests from people of various ages. The youngest client is five, and the oldest is 93. There are 20 staff members, and they still can’t meet the demand for their services.

In recent years, The Center has borne the brunt of DeSantis’s anti-LGBTQ+ policies. Wallace says, “The Center is primarily funded through federal subsidies and corporate sponsors who provide donations. In 2021, Governor DeSantis cut funding for our mental healthcare programme. The Florida House of Representatives and Senate had approved our application, but he refused to sign. We can’t rely on getting money from the state. As long as he’s in office, we won’t apply for funding anymore. I won’t spend our hours on this when he’ll just veto it again. We’ll continue with the help of private donations and some money from the City of Orlando. The care is much needed — just our food bank alone has 700 visitors every month…”

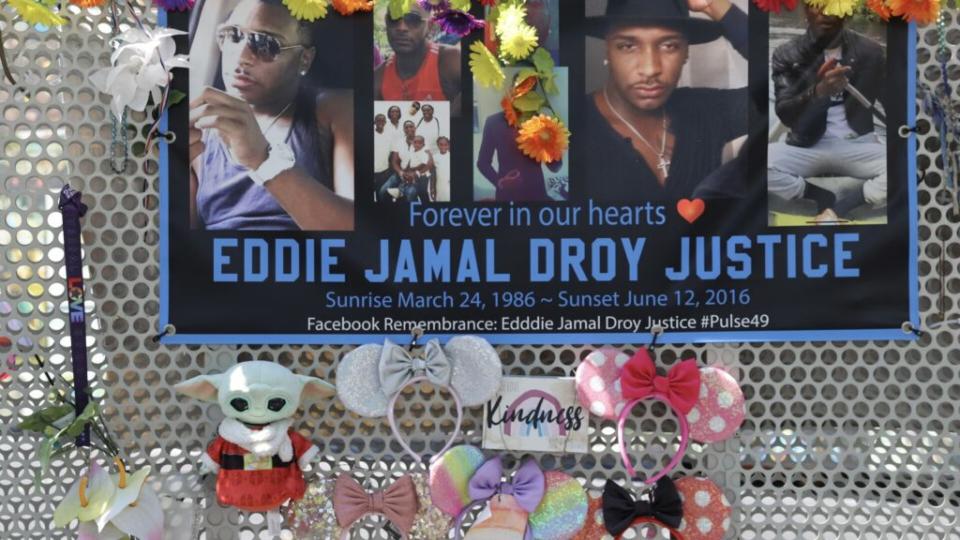

49 Angels in America

At 1912 South Orange Avenue is the building housing queer nightclub Pulse, where, on 12 June 2016, 29-year-old Omar Mateen fired his automatic weapon. Of the 49 people who lost their lives, most were Latin American. Mateen had pledged allegiance to ISIS in Syria, driving him to commit the act of terrorism. Incidentally, a few days before, Mateen had also attended GayDays at Disney World.

Afterward, the city government, the City of Orlando wanted quick possession of the building where the shooting occurred and reached a purchase agreement of $2.2 million with the owner of Pulse, Barbara Poma.

However, a day before the agreement was to be signed, Poma changed her mind — the building couldn’t go into public hands. Instead, she set up onePulse Foundation, with a mission consisting of several components. One of them was the construction of monuments to remember those affected by the Pulse tragedy. Originally, these were to include a museum, a memorial, and the Orlando Health Survivors Walk — an outdoor museum along the path where survivors were carried to the adjacent hospital on the night of the attack.

In the wake of the shooting, plans were made for one or more memorials near the Pulse nightclub. A design firm from Paris was commissioned to propose a monument that was estimated to cost a million dollars. Not exactly realistic. Plans to establish a museum inside the building where the Pulse club was located didn’t proceed smoothly either…

Speaking in 2023, the executive director of onePULSE Foundation, Barbara Bowie, told me: “Barbara Poma is the founder of the onePULSE Foundation and was also the executive director in the first years. While she was in the employ of our Foundation, Poma sold the building housing Pulse to the same Foundation. I consider that poor governance, and as if all that mess wasn’t enough, it later came to light that her insurance covered the building damage.

“The Foundation’s board then didn’t want to pay for the property anymore — making money twice from the same thing, what we call double dipping — and that was enough reason for the club’s owner to distance themselves from the onePULSE Foundation.”

Although its previous attempt to buy the Pulse building fell through, at the end of October 2023, Orlando’s mayor announced the City of Orlando’s intention to buy it, so that a permanent memorial could finally be set up on site. Shortly afterward, onePULSE Foundation said they no longer planned to set up a museum, but a memorial instead. Then came the news in late November that the board of onePULSE Foundation had decided to cease its activities and dissolve the Foundation.

A statement said: “Our vision was to honour the 49 lives taken, survivors and first responders, and to permanently preserve the site of the tragedy. We developed an ambitious agenda to fulfil these mandates and received positive support both locally and globally.

“Unfortunately, best intentions are not enough. We have been challenged by unexpected and definitive events, among them the inability to secure a full donation of the Pulse nightclub site from the property owners and a global pandemic that brought with it critical limits and many unanticipated consequences that ultimately impacted our fundraising efforts.”

The statement continued: “We are offering the City of Orlando and Orange County access to all existing planning and design materials and all the valuable work over our six years of working with those so deeply affected by the Pulse tragedy.”

This puts the establishment of a permanent memorial firmly in the hands of the City of Orlando. While they wait, families and friends of the 49 must continue to make do with the temporary memorial. “To provide everyone a place to return to, we’ve built a wall around the building where people can hang memories. This is a temporary monument,” said Bowie before the Foundation was dissolved. “The owner isn’t pleased with the wall, but we couldn’t just wait for years — people need a place to mourn…” In the meantime, Poma is also involved in several lawsuits with the victims’ families who allege that Pulse didn’t have proper escape routes. These cases are likely to be heard in 2025.

Away from the legal wranglings around the ownership of Pulse, DeSantis has exerted his own negative influence on the tragedy’s aftermath. After he initially helped raise $1m for a Pulse memorial, on the shooting’s fourth anniversary he publicly stated his commitment to stand by the survivors.

But a year later, in June 2021, DeSantis vetoed two LGBTQ+ initiatives: $150,000 that was destined for the Orlando United Assistance Center — part of The Center organisation — which provides counselling and employment services to Pulse survivors, and $750,000 that was due to go towards youth housing.

The decision came a day after he signed a bill barring trans athletes from competing in school sports matching their gender.

Find out more at gaydays.com, comeoutwithpride.org, thecenterorlando.org, onepulsefoundation.org

This feature first appeared in the January/February issue of Attitude, available now.

The post How safe is Orlando for LGBTQ people in ‘Don’t Say Gay’ Florida? appeared first on Attitude.