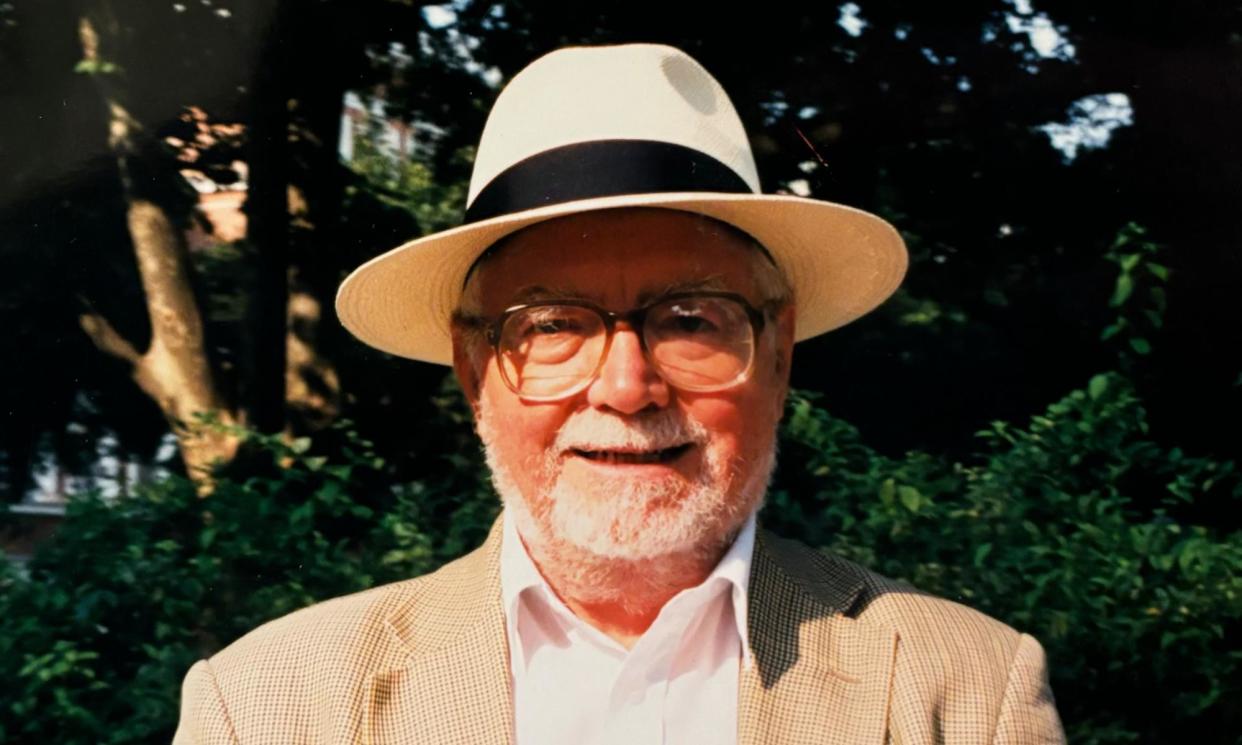

Roy Bridge obituary

My mentor and friend Roy Bridge, who has died aged 85, was the foremost authority on the foreign policy of the late Habsburg empire.

He became a leading expert with his first book, From Sadowa to Sarajevo: The Foreign Policy of Austria-Hungary 1866-1914 (1972), later expanded as The Habsburg Monarchy Among the Great Powers, 1815-1918.

Grounded in meticulous research in the Vienna archives, those works firmly established the subject of Habsburg diplomacy in the context of the 19th-century struggle of the European great powers. Roy revealed the dilemma that faced the Habsburgs: how best, as a weak power with an enormous land mass, to survive in a fast-modernising Europe? He explained how, with increasing fears of encirclement, Vienna’s ruling elite became paranoid, resulting in their decision in 1914 to attack Serbia and risk a European war.

Roy was never an apologist for the Habsburgs, but he was keen to show why their diplomats acted as they did with all their foibles and vanities. Only occasionally did he align his own views with his research topic. He was suitably affronted when, after visiting Sarajevo in 1979, I presented him with a lapel badge of Gavrilo Princip, the assassin of Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

Born in Davyhulme, Greater Manchester, Roy was the son of James and Marian (nee Barrow) who both came from farming families. After attending Ashton-in-Makerfield grammar school he opted for history at King’s College London.

In 1964 he became a lecturer at the London School of Economics and spent eight years there before transferring to the University of Leeds with a remit to introduce “international history” into the curriculum. Effectively this became a department in its own right within the school of history, if not a cuckoo in the nest. From the 1970s it made Leeds one of the UK’s most creative history centres.

Roy’s academic expertise was shown in his book, The Great Powers and the European States System, 1815-1914 (1980), which remains the standard work in the field. He always urged his students to write tightly and to “be kind” to the reader.

He relished socialising with undergraduates, though sometimes with mixed results. At one history society dinner in Leeds he demanded that Viennese waltzes be played alongside the prevailing disco, and was exasperated when the students studiously ignored the records he had brought along.

Having retired from Leeds in 2000, a decade later he was awarded the Austrian Cross of Merit (first class) for achievements in science and arts. It was a fitting tribute to an innovative scholar and dedicated teacher.

He is survived by a son, Maximilian, from his marriage to Susanna Bernbeck, which ended in divorce, a granddaughter, Caroline, and his sisters, Margaret and Alison.