My rent has gone up £300 a month’: Pain of soaring costs and zero hours contracts

Urwah Chaudhary is one of millions of Britons struggling with the cost of living and record-breaking rent price increases.

The full-time student, who works as a call centre agent on a minimum wage and on a zero-hours contract, has faced a monthly rent increase from £900 to £1,200 in the space of a year.

Inflation, the increase in prices in the rental market in her local area, and a struggle to afford the mortgage after successive Bank of England interest rate hikes, were the reasons given by her landlord for the hefty additional monthly outlay.

The increased cost of basic items, such as food and energy, and the precarious nature of her work, have left her with a serious shortfall at the end of every month.

She said: “The situation is frustrating and stressful. At the end of the month, I am living hand to mouth. I’ve had to borrow money from my dad or get help from my partner.”

She added: “I’ve had to massively cut back on my groceries and just focus on the essentials such as bread and milk, things like that. I’ve not been able to do much socially or have takeaways.”

The 22-year-old, who lives in Chelmsford, Essex, says her weekly hours vary from 30 to as few as five. This has meant she has taken on additional work delivering food through apps to ensure she has enough money to get by.

Private rent growth is now seriously outpacing general inflation. @jrf_uk we've looked at the picture since April 21, when prices really began to take off.

Private rental growth (9.1%) on average across Great Britain is now almost 3 times as high as overall inflation (3.2%). https://t.co/AMZbxKmVOI pic.twitter.com/8cHicGBqXq— rachelle_earwaker (@r_earwaker) April 17, 2024

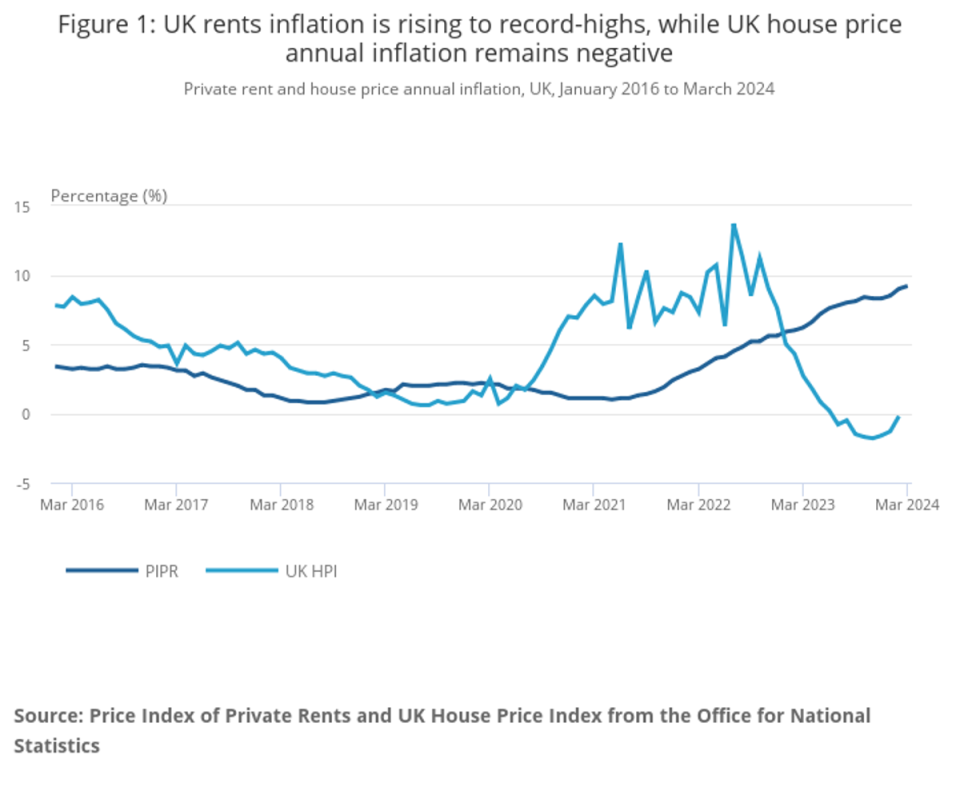

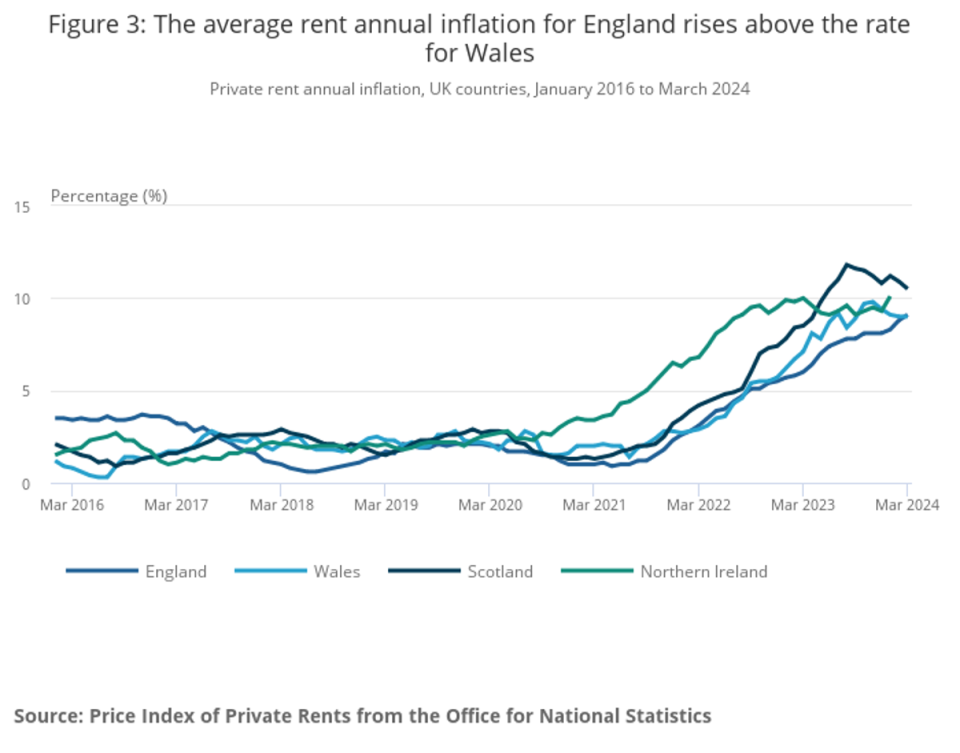

Ms Chaudhary’s large increase in rental costs and struggle with the cost of living are not uncommon. Data from the Office for National Statistics released this month showed that average rents jumped by 9.2 per cent in March: the biggest annual percentage increase since data collection began in 2015.

Rocketing rents are rapidly outstripping inflation, which measures price hikes in other essentials including food and energy and has come down to 3.2 per cent, leading campaigners to warn that tenants need protection from unaffordable increases.

Analysis conducted by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) showed UK rents increased by an average of £104 a month over the last year and in London by £207 per month.

Rachelle Earwaker, senior economist at the JRF, who conducted the research, said that “historically high rent increases” are seeing little signs of slowing down despite a steady fall in inflation.

She added: “Even with the recent increase to housing benefit, this will leave many renters without any disposable income whatsoever. Renters who can’t absorb these costs risk being evicted from their home.”

Double jeopardy of high rent and zero-hours contracts

Ms Chaudhary is one of many tenants facing the precarious double whammy of high rental costs combined with insecure work, leaving them in a more perilous financial position.

Analysis published by think tank the Work Foundation said that 1.4 million workers face the “double jeopardy” of being in insecure work and living in the private rented sector, as private rents hit record highs.

Its analysis shows that this is particularly challenging for workers with the least secure work, who are on average £3,200 per year worse off than those in full-time jobs.

‘My mum has to buy my shopping’

Louise, 35, a single mother of three from the West Midlands, is on a zero-hours contract as an NHS worker. Her fluctuating hours, combined with £1,200 a month rent, makes budgeting difficult.

She said: “It’s hard month to month, it’s really hard. Quite often I’m finding that my mum will do the food shopping one week just so that we’ve got something to eat when I’m a bit stuck financially.”

“We don’t go on holidays because the cost of living is too much. It all makes you feel very stressed.”

She added that the constant rent increases “does worry me a lot” along with the uncertainty of whether she will have to move her family again when her tenancy comes to an end.

“That’s another thing that is hard; not knowing whether or not you’ll be able to renew your contract and then you’ve got to try and find another house, within the same budget and same area as prices are rising,” she said.

Another major factor affecting renters is “no-fault” Section 21 evictions: a legal mechanism allowing landlords to evict tenants without providing a reason. These were meant to be banned as part of the Renters (Reform) Bill, but are now subject to “an indefinite delay”.

‘I cannot afford to live alone’

Ella Fraser, a TV production assistant, currently pays £1,050 for a one-bedroom flat in south Ealing, west London, but she is coming to the end of her contract and faces paying £300 a month extra in payments.

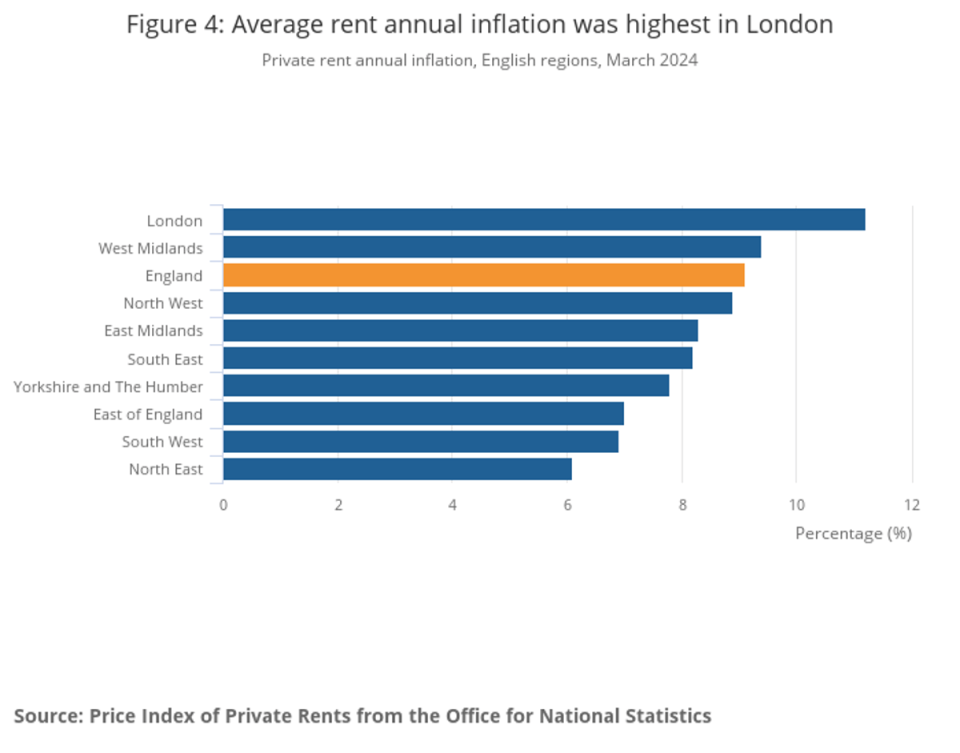

Average rent inflation is highest in London at almost 12 per cent, and like many, Ms Fraser is being pushed right to the edge of what she can afford, with other properties in the same area even more expensive.

The 29-year-old said that even though she has a generous salary and full-time contract from her employers, the rental increase and other costs have left her fearing she could have to take a second job, or even leave the capital, putting her career in jeopardy.

She said: “Salaries are just not keeping up with the escalating costs of things like rent, and everything else, such as energy or food. The increased costs mean a significant reduction in my standard of living... I could leave London but it could impact my career, and I’ve worked so hard to get to this position.”

Ms Fraser, who is single, said the situation around housing is so precarious that it will force people to make decisions around relationships they would not normally make.

“Even I have thought maybe I should be in a relationship so I can share costs with a partner and it might help me save for a house. That’s the awful situation the housing market is in.”

She added: “I feel like as a renter I have no breathing space to do anything and no spare money to save for a house. I don’t have a family who can help, there will be no inheritance for me that can help me get on the housing ladder.

“I, and others in my generation, will likely be renting for life so the housing market needs to be more affordable.”

There are 4.6 million households that use the private rented sector in England, with 11 million renters.

Rent now accounts for 28.3 per cent of income

Last year, rents as a proportion of income accounted for 28.3 per cent, compared with 27 per cent on average for the past 10 years, according to figures from property website Zoopla.

Ben Twomey, chief executive of Generation Rent, said: “The fact rents are rising faster across all tenancies than on new tenancies tells us that this is being driven by landlords raising the rent on their existing tenants.

“Tenants have very little power to resist these increases, beyond our raw negotiating abilities – and these are hobbled by the fact that a landlord can evict us without needing a reason if we challenge a rent hike.”

Tom Darling, campaign manager at the Renters’ Reform Coalition, said: “England’s rental crisis summarised: millions of people paying through the nose to live in substandard conditions, afraid to complain to their landlord for fear of eviction.

“The government don’t have a serious plan to tackle rental affordability, but even when it comes to renters’ security in their homes, they are dropping the ball.

“Just this week they passed a neutered Renters (Reform) Bill, which was meant to end no-fault evictions, but now doesn’t guarantee they will ever end. We’ll be doing everything we can to strengthen it in the House of Lords.”

A government spokesperson said: “Our Renters (Reform) Bill will deliver a fairer private rented sector for both tenants and landlords, and we are investing £11.5bn in the Affordable Homes Programme as part of our long-term plan for housing.”