All the rage: Why we need angry girls in children’s books more than ever

Two summers ago, I was in the middle of a tricky draft for a children’s book. My heroine was a ghost, but that was all I knew. Doubt crept in. What, exactly, was I writing? Then Serena Williams had a bad day on the tennis court and everything changed.

You probably saw the images. When Williams lost her temper in the 2018 US Open final, every second of outrage – pointing her finger at the umpire, breaking her tennis racket – was captured by a lens. While furious male tennis players rarely make it beyond the sports section, a female athlete’s anger was singular enough to be splashed on front pages around the world. An Australian newspaper depicted Williams as a grotesque giant baby in an infamous cartoon. Later that year, the #TimesUp and #MeToo movements gained momentum, fuelled by the fury of women refusing to be silenced any more. In an interview with Vogue that autumn, languid priestess of cool Phoebe Waller-Bridge talked about women’s anger as if it was an art form. “I’ve always found female rage very appealing,” she said.

From where I was sitting, it sounded like a dare. The touch paper inside me was lit. My children’s book Storm began to take shape properly, with a heroine who was “born raging”: Frankie Ripley.

Although her family is a happy one, Frankie’s a volatile 11-year-old with a temperament given to extremes. She occasionally sets fire to things, slams doors, shouts. But like most children, she is never given permission to fully explore, express, or release her ire. Early on in the book, she’s told, in time-honoured tradition, to go to her room until she calms down. Her temper writhes inside her, desperate to be articulated, and heard. This leads her to wonder, as she stamps up the stairs: “What happens to strong emotions if you’re not allowed to feel them? Where do they go?”

We soon find out. A natural disaster wipes out her entire village, and Frankie dies. A bit. All that unresolved ferocity within her prevents her from dying properly. She forges a new existence as a poltergeist – the angriest ghost there is.

During the writing of Storm, I grew a tiny bit concerned. Was her personality a bit much? Should I tone it down? My editor didn’t seem to think so. If anything, he urged Frankie on. (In one memorable email, he suggested, “Maybe Hulk her out a little more?”) Still I worried: how would my angry girl be received? Would she be pilloried, like Serena?

But the women behind #MeToo had shown me there was safety, not to mention credibility, in numbers. In search of solidarity, I skulked around bookshops and Twitter, asking readers, booksellers, and authors where the other angry girls were, hoping to unearth some kindred spirits.

When it came to the classics, Mary Lennox in The Secret Garden was suggested, but closer reading suggests Mary is more unhappy than angry, a neglected child who “never seemed to really be anyone’s little girl”. We are often told within the pages of Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time that the main character Meg is angry, but by modern standards her anger could more easily fall into the “assertive” or just “grumpy” category. (Or even, dare I say it, normal?) A few even suggested Anne of Green Gables and Pippi Longstocking, which led me to wonder by what standards we were even defining female anger within children’s literature.

In the much-loved older classics that are still read today, we also have a tradition of angry girls who believe that it’s a “bad” side of them, and that they must learn to master or control their anger and are often rewarded for doing so. Jo in Little Women always feels guilty for her temper, for example, and Darrell Rivers in Enid Blyton’s Malory Towers is often seen “struggling” with her fierce temper. For an extreme example, Katy Carr in the 1872 Susan Coolidge classic What Katy Did is a headstrong, impulsive child, who in a symbolic turn of events that now seem about as subtle as a brick, is injured and confined to a wheelchair, only able to walk again once her entire personality is transformed. The take-away lesson from these books is unmistakable – lose your anger, and you will be an acceptable woman, worthy of love and capable of agency.

That’s not to say you can’t find recognisable anger in modern books. I was also told about spiky, frustrated, surly heroines to be found in books for all ages. Rebecca Patterson’s picture book My Big Shouting Day features a frankly inspirational toddler articulating her frustrations on every marvellous page. For slightly older readers there are Connie in Katherine Rundell’s The Explorer, Lark in Eloise Williams’ Seaglass, Fidge in Lissa Evan’s brilliant Wed Wabbit, to name just a few. For pre-teens and above, there is Lexi in Jenny Downham’s Furious Thing (a memorable party scene early in the book acts as a microcosm for society as a whole, and reveals Lexi – and us – have plenty to be furious about), while CJ Skuse’s Monster and Sally Nicholls’ Close Your Pretty Eyes both have angry heroines.

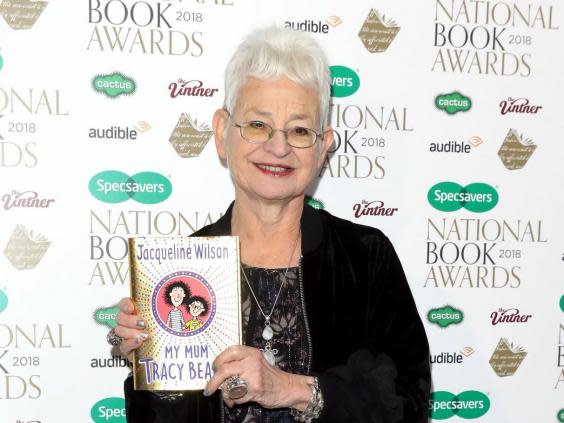

But these girls and their canonical sisters seem to come with certain conditions. One: they are allowed to be angry as long as this is justified by a backstory that reveals trauma, grief, neglect, or abuse – see Jacqueline Wilson’s Tracy Beaker books. Or two, their anger is a form of care-giving: their fury is selfless and prepares them for motherhood, or looking after others. Dahl’s Matilda, Rowling’s Hermione Granger, Philip Pullman’s Lyra Belacqua, even Katniss Everdeen in The Hunger Games series, all spend a lot of time getting angry on behalf of other people. For example, while Harry Potter spends vast swathes of time feeling angry at his life – in other words, it’s all about him – Hermione only really gets properly angry on behalf of other people, such as the house elves. Roald Dahl’s Matilda uses her anger to oust Trunchbull and save an entire school. Even the canonisation of Greta Thunberg, you could argue, carries on this great tradition – a spiky heroine for our time, speaking truth to power, who we love for getting angry on our behalf.

Does this mean that fictional girls are only allowed to get angry if it’s for the greater good? And if so, are we inadvertently shaping female anger into just another mode of caregiving for girls? I can’t claim immunisation from this concept – that’s exactly what happens, ultimately, in Storm. Frankie uses her anger to... well, you’ll have to read it to find out.

Stories of kindness and social justice will always be important. But in an age of increasing awareness for a push for diversity in the market of children’s literature, perhaps we should also be considering diversity in representations of temperament. Maybe we could allow our fictional girls to be angry for reasons other than harrowing backstories and social justice? Could we, in other words, present anger as something that’s just... there, without having to justify or sweeten it? Where are the fictional Serenas, getting furious in the heat of competition? Would other volatile, not neurotypical children, or children who feel things more deeply, find themselves “seen” in ways they might not now?

Commercially, this comes with risk. Imogen Russell Williams is a children’s book critic for several national newspapers, with a decade’s worth of experience of reviewing children’s books across all ages. She feels children’s literature can be panned if it features a heroine who is not immediately endearing. “You can have male anti-heroes crawling out of the woodwork, but if a female lead is not likeable, it really stirs up readers. I see so many reviews for books where the readers say they didn’t like the heroine, and as a result they didn’t enjoy the book, or see that it had any artistic merit, and give it a low review.”

And – with so many titles to compete against – perhaps it’s no wonder that female heroines are packaged in a way to make them sell. Which in turn can create heroines that almost seem homogenous; feisty, plucky, occasionally angry but with good reason, inherently kind, inherently good. Team players – eventually. Which begs the question: if we censor fictional girls for their dispositions, what on earth are we doing to actual flesh and blood girls?

“Almost always, the families I observe see anger as a negative emotion. While the sight of a sad child creates empathy, an angry child is much harder to ‘sit with’ – and so parents often want to close that anger down and get rid of it,” says Bonamy Oliver, a developmental psychologist who conducts research into family relationships. “This can lead to repression, which in turn can lead to all sorts of problems down the line, self-harm amongst them.”

Oliver’s not the only one who sees the consequences of female anger being repressed. In a collection of recent essays, Rage Becomes Her: The Power of Women’s Anger, Soraya Chemaly notes the medical data on teenage anorexic girls, and their high statistics of recorded repressed anger. Women and girls, she argues, are permitted a “narrow line of emotional expression” and their anger is frequently not permitted. Like Katy, girls are still being confined by what they are not allowed to be.

What does this have to do with the books I buy for my children, some might say, arguing that gender politics should be kept out of it. This is valid – but equally valid is the counter-argument that literature for children is highly formative when it comes to constructing identity, and gender politics are everywhere, whether we like it or not. Arguably, the people suggesting we keep politics out of children’s books are the ones for whom politics do not need to change.

The stories we tell children will shape the stories they tell themselves about their place in the world and their standing in it. Ideas about power, repression, and who has legitimacy in discourse run through our world as much as they ever did.

So maybe girls internalising the idea that they must be likeable before they can be anything else isn’t something we can just accept passively anymore. Maybe we need to allow more anger, in different guises, and for all different reasons. And if we want to create a new generation that is not afraid to speak up, maybe we need to create female forces of disruption, with a multitude of voices. Perhaps we need little firestarters more than ever.

‘Storm’, by Nicola Skinner, will be published on 2 April by HarperCollins