Why Prince Harry could be addicted to litigation

In the late noughties ITV comedy drama Kingdom, starring Stephen Fry, the character of Sidney Snell was constantly bringing legal action against the local council. Snell, albeit fictional and played for laughs by Tony Slattery, was cited in an academic journal a decade later as nicely illustrative of “the concept of the hyperlitigious person”.

Entitled “I’ll see you in court… again”, a 2017 article in the Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law described this psychiatric phenomenon: of individuals who “frequently inhabit the doorways of law offices and courthouses, each time with a new complaint against an individual or a group of people. The cost or consequences of litigation are sometimes trivial to these clients, whereas retribution for a real or imagined slight or injustice is their foremost priority.”

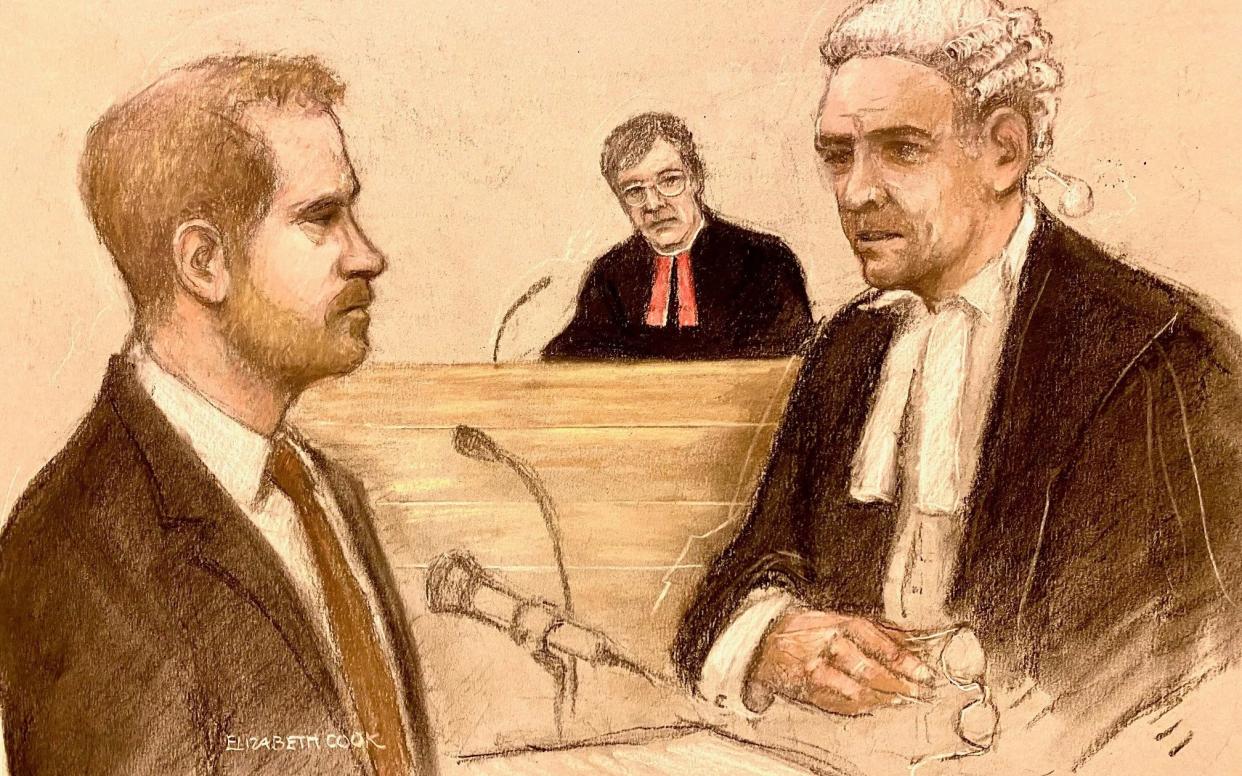

Does this remind you, perhaps, of any California-based member of the British Royal family? This week, the Duke of Sussex is back in court again – this time in person – as he brings his legal case against Mirror Group Newspapers (MGN). He alleges that 147 articles published between 1996 and 2010 by Mirror titles contained information gathered using unlawful methods, with 33 of these stories selected to be considered at the trial. MGN has told the High Court in London it denies that 28 of them involved unlawful information gathering, and that it was not admitted for the remaining five articles.

To put it mildly, this is not the Duke’s first rodeo. He has, for several years, been doggedly turning litigation into something of a vocation. After voting for Megxit with his feet, publishing an explosive, accusatory, score-settling memoir, and starring in all six hours of an explosive, accusatory and score-settling Netflix documentary, Prince Harry apparently still has scores to settle.

You’d be forgiven for losing track of his various lawsuits, which have been troubling the courts since 2019, when he launched legal action against the owners of The Sun, the defunct News of the World and the Daily Mirror over alleged phone-hacking dating back to between 1996 and 2010. The following year, he sued Associated Newspapers for libel over two articles claiming he had “turned his back” on the Royal Marines after stepping away from frontline royal duties. The publisher reportedly paid “substantial damages” to the Duke.

In 2021, the Duke and Duchess of Sussex issued a legal letter to some news outlets, via Schillings law firm, accusing the BBC of “false and defamatory” reporting in an article that claimed the couple had not asked the late Queen about naming their daughter Lilibet.

The above is not an exhaustive list, merely a selection. In May 2019, the Duke accepted substantial damages from Splash News and Picture Agency for taking photographs of his Cotswolds home from a helicopter. He is one of seven people bringing legal action against Associated Newspapers over allegations it carried out or commissioned unlawful information gathering (which the publisher has denied). He is also pursuing legal action against the Government over his security arrangements.

Is it possible, then, that he has become addicted to litigation itself? It is certainly possible to argue – as some have – that he views himself as the leader of a moral crusade against what he views as the egregious conduct of the British media. He has, after all, described his efforts to change the media landscape as his “life’s work”. It also seems conceivable that the sense of purpose that drives him may have given way to obsession, if not full-blown addiction.

“Generally, addiction is when a habit tips over to the point of affecting one’s life and wellbeing,” says Dr Sheri Jacobson, founder of harleytherapy.co.uk and a retired psychotherapist.

Those who become fixated on litigation are generally motivated by a desire, whether misplaced or justified, to restore justice. “So you believe a wrong has been done and you’re willing to put the time, effort and resources into redressing that imbalance. When we do it often, we have to wonder whether that (perhaps overdeveloped) sense of justice is the driving force rather than the actuality of the event.”

In some cases, the very litigious person may be “deflecting away from other difficulties,” Dr Jacobson suggests. “In some ways it can be more straightforward to go for a target that’s current rather than someone in the past who has wronged you.”

While some might, by sheer bad luck, have genuinely been repeatedly wronged, others might have a bias towards seeing themselves as victims of injustice, potentially due to being victimised during childhood, she adds.

But repeatedly bringing litigation tends not to bring the fulfilment the person may hope for. “Hyperlitigious people often live unhappy, frustrated, difficult lives in which they obsess continuously about their pending lawsuits,” write Stanley L Brodsky, professor emeritus at the Department of Psychology, University of Alabama, and his co-authors of the 2017 article on the subject.

Lawyers, too, are familiar with the phenomenon of the hyper-litigious. “There are certainly people [who do this]; but those people need to have deep pockets [in order] to fund repeated litigation,” says Persephone Bridgman Baker, partner at the law firm Carter-Ruck. “At the very minimum you’re looking at hundreds of thousands of pounds on each side of [the Duke’s case], with the loser potentially bearing the majority of the winner’s costs.”

If either side goes on to appeal the decision, total legal fees could be much more than that, she adds.

It is easy to play armchair psychologist and guess what might be driving someone willing to repeatedly put so much at stake. Hard, in Prince Harry’s case, to ignore his anger over his mother’s death, for which he blames the media. Hard to rule it out as a motivating factor behind his committed pursuit of the press through the courts. But royal biographer Angela Levin is still at a loss to work out why he appears to want to “self-destruct” via the courts.

“I think he’s become obsessional now,” she says. “He’s trying to blame everything on the press and get a lot off his chest. It sounds like something he’s going to keep on grinding at and will never give in.”

When Levin interviewed him six years ago, he was “lively, charismatic, cracked jokes and was a delight to be with,” she says. “Now he’s not even a shadow of himself.”