How the cost of your plane ticket breaks down – from crew salaries to airport fees

Strikes, illness and inclement weather have all plagued British air travel in recent years. And now, the Civil Aviation Authority, the industry’s regulator in the UK, has announced that it is increasing air traffic control charges – ostensibly to alleviate these issues.

The charge is paid by the airlines to the National Air Traffic Services (Nats) for its air traffic control capabilities. The fee will rise from £47 to £64 per flight until 2027, which equates to an average increase of 43p per passenger to £2.08.

It is not, admittedly, a large amount of money. But the fee is one of many that makes up the typical airline ticket, with fuel costs, government taxes and security fees all contributing to the final price.

By law, all these unavoidable fees must be advertised as part of the ticket – meaning that the price you see should be what you pay. But airlines do have some discretion, and can charge variable additional amounts.

Air Passenger Duty

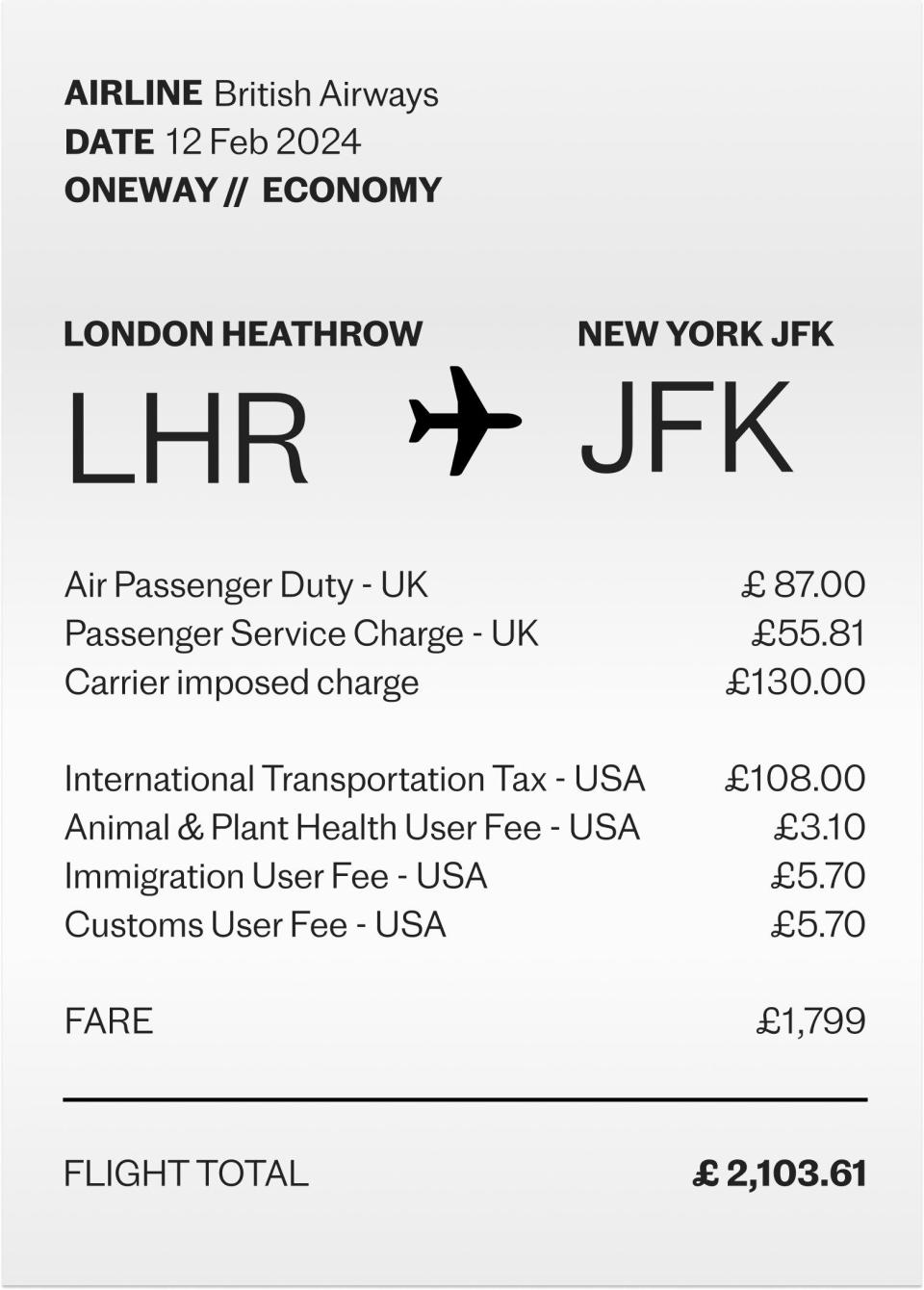

Some, however, are fixed. Air Passenger Duty was increased earlier this year, meaning that most short haul flights with economy passengers are taxed £13 each by the government. On long haul, the amount increases to £87, or £91 for trips over 5,500 miles long.

The rates for premium economy, business class and first-class passengers are considerably more – the most expensive seats on the longest flights, for example, will include £601 of APD. The changes earlier this year did, however, make domestic flights slightly cheaper, with the tax being halved from £13 to £6.50 per passenger.

Fuel costs

Then there’s the fuel tax, often listed as a “Carrier Imposed Charge”. These were first introduced by airlines in 2004, as the price of oil rocketed to $40 (£22.32 in 2004) a barrel. This stabilised, but the charge has remained for some airlines.

This year, IATA reports, fuel accounts for 28 per cent of an airline’s costs, although this has fluctuated wildly. In some countries, like Australia, New Zealand and Hong Kong, the charge is closely regulated, meaning the costs cannot be entirely passed on to the customer.

This is not the case in the UK. Taking a British Airways flight from London to Barcelona as an example, the fee for travellers in the UK works out at just under three per cent of the ticket price. Some budget airlines, like easyJet, do not include it in their fares.

There are not, however, taxes on jet fuel in the UK for airlines themselves, unlike the fuel used by almost every other form of transport. Nor is there VAT on plane tickets (unless you’re flying on a private jet).

Airport fees

That’s not all – your ticket could also include journey-specific costs. A Passenger Service Charge covers the amount that airports charge airlines to use their services. In the case of the Barcelona example, this becomes £23.18 (or 16 per cent) of the final amount. This number, somewhat controversially, varies between airports. Earlier this year, Heathrow was forced to cut its landing fees from £31.57 per passenger to £25.43 from next year, after a years-long row.

As with many elements of air travel, the breakdown of charges altered after 9/11, too. Insurance and security costs were imposed after 2001 to account for the additional processes involved in flying, and again, these vary between airlines. These appear more often on routes operated by US-based airlines, but they can, according to IATA, be charged by UK airlines if clearly labelled.

The “final fare”

Even after these charges, the amount remaining is not entirely profit. It’s estimated that labour accounts for around a third of an airline’s operational costs, which, alongside fuel, is the largest overhead. Smaller charges, like the Nats fee, will likely be wrapped into the final “fare” on a ticket, rather than listed separately as the taxes are.

Figures from the US Department of Transport can be used to estimate what each element of air travel costs. Roughly two thirds of the “final fare” are spent on staffing and fuel. Plane leasing and ownership eats into six per cent of the ticket price; about the same goes on non-aircraft assets like hangars and offices. The cost of complimentary refreshments, landing fees, maintenance, insurance, and advertising all take a smaller chunk. And these numbers do not include governmental fares, which, as the example ticket of BA flights to New York shows, add on more than £100.

These figures are, of course, only looking at American airlines, and are averages, but offer an insight into how our ticket fares are spent beyond the compulsory fees.

The profit

As for the final profit? According to the International Air Transport Association, airlines are taking home an average of $4.36 (£3.60) in Europe per passenger, and $9.53 (£7.87) in the US. Worldwide, the average profit margin amounts to just $2.25 (£1.86) per passenger.

This final amount does not take into account ancillary profits. Additional costs, from seat fares to on-board sandwiches, comprise a large wedge of the money made by airlines. In May, it was reported that Ryanair earns around £20 from the typical passenger, largely through smaller purchases like seat reservations and snacks.

It’s worth noting that the final price of a ticket can change, too. If the “unavoidable charges” are reduced by the government at any point after purchase, there may be an option to claim a refund (although this, again, varies between operators).

Unfortunately, the reverse also applies: you “may be required” to meet the new amount if there’s a substantial increase, too. Regardless, in the UK, the additional costs should always be advertised as part of the ticket price – so there shouldn’t be any surprises.