Party Lines: Dance Music and the Making of Modern Britain by Ed Gillett review – the fight for a rave new world

Never mind “repetitive beats”, a keystone of the infamous 1994 Criminal Justice Act that effectively banned raving in fields, the story of UK clubland has also been told again and again, lionising a very British cultural phenomenon. It usually goes like this: in 1987, a coterie of UK DJs went to Ibiza and came back transformed by Balearic dancefloor sounds and MDMA. Paul Oakenfold, Johnny Walker, Danny Rampling and Nicky Holloway returned and founded acid house. Raves, the Haçienda and the rise of the superstar DJ followed.

This origin myth glorifying four white men may be true, argues journalist, documentarian and club enthusiast Ed Gillett, but the Ibiza Four legend disregards the fertile soil in which their endeavours took root: one of free parties, Black blues dances and hippy convoys. It was an anti-authoritarian, pleasure-seeking tendency now, 35 years later, corralled into “cultural economy” mega-clubs run by, and for, the more privileged.

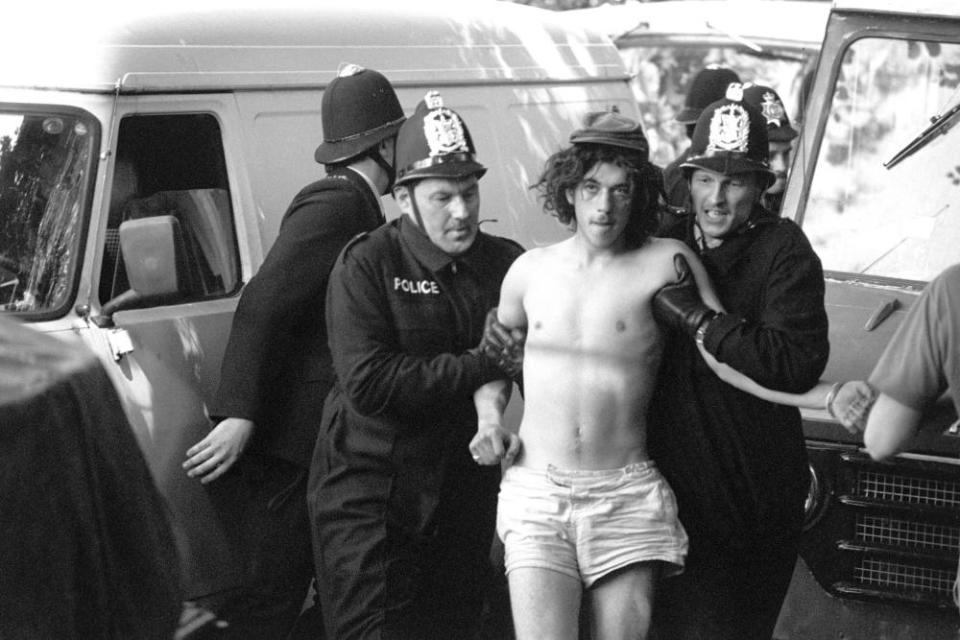

In 1990 a rave outside Leeds was violently shut down by West Yorkshire police

This engrossing doorstop of a book is indelibly steeped in dance music culture, analysing how we got from thrilling early imports of Chicago house music (played in Black spaces first), via the British rave explosion, to what he calls “business techno” – Gillett’s superbly sniffy coining for today’s sanitised, mainstream clubbing fare. But there is also a thin blue line running through the pages, making it an important book about policing, policy and politics too.

Policing strategies, Gillett argues, connect a seemingly disparate group of partyers, nomads, sound system DJs, queer space organisers, drill rappers and activists; pretty much anyone who has ever found themselves on the wrong side of a truncheon or punitive court case. The UK has just passed the Public Order Act, an historic piece of legislation suppressing political dissent – the latest instalment in a continuum of increasing police powers that includes the Criminal Justice Act, which increased powers to stop and search, demonised electronic music and criminalised “disruptive trespass”.

Gillett makes plain the continuum of police suppression. Tactics used against striking miners were applied to moon-eyed ravers. In 1984, police blocked London’s Dartford Tunnel in a ploy to stop Kentish miners from supporting their striking colleagues in Nottinghamshire. A subsequent high court ruling found the commanding officer had exceeded his powers.

Five years later, that commanding officer, Ken Tappenden, was the head of the Pay Party Unit, tasked with stopping raves across the nation. (Its unofficial logo? A police badge with a smiley face at the centre, crossed out – discovered by Gillett in police archives.) Once again, Tappenden operated at the greyer end of legality, threatening companies supplying sound equipment, lighting rigs and marquees.

Elsewhere, the scenes were far uglier. History remembers the Battle of the Beanfield in 1985, when Wiltshire police went in hard against a convoy of new travellers (“new age” is a coining they reject). Then in 1990, another rave just outside Leeds was violently shut down by West Yorkshire police. It was no accident: this was a force battle-hardened against its own miners, enacting, Gillett reckons, the biggest mass arrest in UK history.

It’s no great leap to segue British social history of the early 80s into that of the late 80s, as Gillett often does here. But his aim is to consciously stitch together events to account for the repressive, authoritarian, fun-sceptic place in which the UK finds itself in 2023. We got here, the author argues, by raiding Afro-Caribbean blues dances, sound systems and gay night clubs, by forcing travellers off the road – and by beating up miners and E’d-up kids.

At the centre of this strategy, he posits, was the Thatcher-era notion of “the enemy within” – which Gillett extends to pretty much anyone the Conservative party didn’t like the look of (early shots, arguably, in what we now know as the culture wars). The arc is historic, he says; possibly going back as far as farmers v hunter-gatherers, with the enclosure of the commons and the triumph of private property rights dovetailing into the authorities’ fear of people congregating and moving about. Naturally, drug laws come in for scrutiny, with Gillett bristling at the demonisation of MDMA as “the enclosure of the periodic table”. Just as the enclosure acts banned commoners from grazing their sheep on land previously open to all, Gillett envisions the status quo arbitrarily banning relatively safe compounds to serve their own interests.

Photograph: Alex MacNaughton/Alamy

Party Lines is a wide and deep undertaking, which relies on substantial research while acknowledging its debt to previous works on rave culture. There are walk-on roles for Guido Fawkes and cult leader Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. At least one other book lives inside it.

Gillett might have easily spun off the harrowing tale of a charismatic rave church known as the Nine O’Clock Service, whose mixture of dance music, community and liberation theology was bringing in so many young people that it received funding from the diocese of Sheffield. NOS was really a cult, with survivors still coming forward with tales of sexual and psychological harm. But Gillett acknowledges the NOS’s profound appeal: spiritual uplift and utopianism, all set to transportive music. Though this is a book often driven by exasperation, a labour of love written with scholarly precision, Gillett’s passion for the transcendental, communitarian experience of dancing shines through throughout.

• Party Lines: Dance Music and the Making of Modern Britain by Ed Gillett is published by Picador (£20). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply