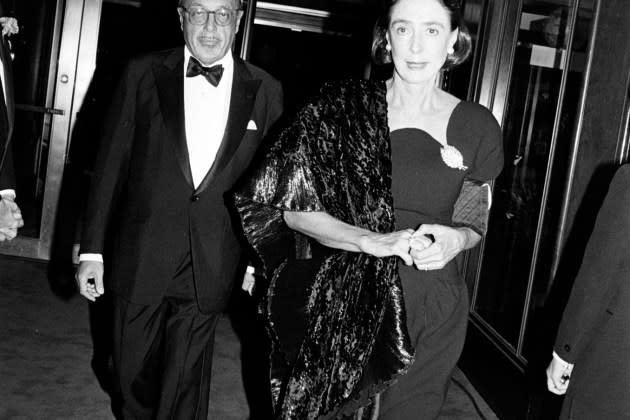

Mica Ertegun’s High Style Stands the Test of Time

Along with being a jetsetter, a New York insider and a working woman, who didn’t have to be, Mica Ertegun had style in spades.

The 97-year-old Ertegun, whose late second husband Ahmet championed such musicians as Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones as Atlantic Records’ cofounder, died Saturday at her home in Southampton, N.Y. After escaping Communism in her postwar Romania, she settled on a Canadian farm before marrying, venturing into interior design, establishing herself as a style arbiter, highly regarded hostess and philanthropist. Her father, Gheorghe Banu, was a Romanian doctor and politician. Her fashion sense stands the test time, based on a few of her interviews with WWD over the years.

More from WWD

Istituto Marangoni Miami to Offer Art Basel Programming With Kid Cudi, Kartell and More

Anthony Vaccarello, Jan-Jan Van Essche Honored at Belgian Fashion Awards

As an interior designer, Ertegun’s Manhattan town house embodied her everlasting style – chic, elegant and expensive. Seven years into the MAC II business that she started with fellow socialite Chessy Rayner, Ertegun said friends had been asking them to spruce up their apartments. The founders had been looking for something to do and they thought it would be “very easy,” choosing their own hours and working with friends. Not quite – “We made a lot of mistakes. I feel a little sorry for our first clients,” Ertegun told WWD in 1976.

Before marrying her husband in 1961, the Romanian-born beauty lived in sweaters and jeans on the Canadian farm. “Not the ruffle type,” her affinity for pants carried over into eveningwear and afternoons in the country. Her de rigeuer daytime attire was primarily the tried-and-true slimmish-skirt-and-sweater combination and favored cashmere sweaters and textured stockings in the same color. Off-hours, she was the consummate entertainer, hosting intimate dinner parties, or catching private screenings, theater openings and the occasional concert.

By her own account, Ertegun kept very few things but her Madame Grès designs were the exception, especially togas. Her irreverent style might consist of black crepe pants with a parrot green toga and ropes of pearls wrapped around her wrists. In 1975, Ertegun clued WWD into the fact that she hated to wear something that everyone else had. So much so that she gave up her Cartier watch after seeing it on many others. A similar scenario played out with a Louis Vuitton satchel that she had seen all over Paris. Her replacements were a man’s wristwatch and an Hermès shoulder bag with a little makeup bag tucked inside.

She saw fashion as a game that you played as long as it was fun. Her intent was to look neat and her clothes had to be simple — seams straight and darts in the right places. (To keep everything just so, she relied on a dressmaker behind-the-scenes.) Ertegun told WWD in 1967, “In New York, everybody recognizes where your clothes are from, even if you avoid the season’s status symbols. The fun of the game is to try to keep them guessing for a little longer.”

To accomplish that in the late 1960s, Ertegun mined finds from downtown stores, uptown thrift shops and then some “assurance-insurance” pieces found in Paris, London, Rome and Zurich. Big coats, gathered skirts and anything cutesy or cut out were off-limits. Braemar, Biba, Adolfo, Pierre Cardin, Madame Grès, Fernando Sanchez, Bill Blass and Chester Weinberg were more her speed. The way she saw things, “One good coat a year is the beginning of any wardrobe.”

A doer, not a primper, Ertegun’s makeup routine came down to soap, water, astringent and a little lip balm. Another time saver was limited hairdressing, since she liked to swim regularly. Striving to — but not always meeting — a goal of exercising three times a week, Ertegun kept her hair long enough to pull back and wore headpieces at night. Her style arbiters were Francoise de la Renta, Annette Reed and Lady Keith — the cultured types who read, knew life and had no time for chit-chat. After noting how she was “fascinated” by Diana Vreeland, Ertegun said, “She’s a doer, too…people who bore me, I just don’t see.”

Progressive in her style, too, Ertegun appreciated versatility — as evidenced by the mink coat with a zip-off hemline, David Evans boots that fastened like stockings and pairing an Yves Saint Laurent “Smoking” with a nightdress styled to be a blouse that she had unearthed in the flea market at Marche Byron in Paris in 1967.

With her day job, Ertegun took a similarly uncluttered approach to decorating — simplicity, drama and non-matching colors. In one of her WWD interviews in the mid-1970s, she described her husband as “amused but approving” of the venture. “After all, our husbands lent us the money to start the business, or how else could we have funded it.”

But Ertegun wasn’t exactly a newbie at interior design, having had a lifelong interest in decorating and a one-year stint at the New York School of Design. But school days bored Ertegun. “Their taste and mine are so totally different. They were talking avocado and gold. I hope American taste has changed.”

The well-heeled Ertegun and Rayner racked up clients like Saks Fifth Avenue, the Carlyle Hotel and Jerome Robbins. And Ertegun took that role seriously, by being dressed and ready to go by 8 every morning. Without question, the socialite didn’t need the money, but she told WWD that she would hate to work and not earn money. “It seems sort of dilettante,” she said. In terms of professional advice, she praised Billy Baldwin’s counsel of “never to use anything or to hire anyone cheap to get a good value for our friends.”

Fashion and home design were just accents in a full and varied life. As she once explained to WWD, “Most of my friends don’t take themselves that seriously. They are more natural and they want to have fun. After all, if it’s not fun, it’s not really worth it. Don’t you think?”

Best of WWD