I’m not surprised Victoria’s Secret has dropped its ‘feminist’ rebrand – I used to work there

I’m not surprised Victoria’s Secret has decided to drop its planned feminist rebrand. Why? I used to work there. I was 19, working in the flagship Bond Street store, when I was told one of the top selling techniques was to ask male customers how my body compared to their partner’s.

Let me explain. This was an improvisation strategy taught to us for when the inevitable would happen: a man arrives at a lingerie shop without knowing his partner’s bra size. We were taught to reassure them that we can still find the perfect gift even without knowing her exact bra size… I just needed to ask them a few questions first.

“Is she bigger or smaller than me?” was the first question I was told to ask, in an attempt to get them to buy something, anything, as it would be difficult to decipher her bra size without her physically in the room. And though I was never explicitly advised to gesture towards my bust when making this enquiry, it did seem like something we were sort of expected to do. The customer reactions were varied. I’d feel the man’s eyes scanning my body and see them trail off as they pictured their girlfriend’s breasts in comparison to mine. Some would squirm and awkwardly stutter their words. Some had brutally kneejerk answers: “No, she’s much smaller.” While most were polite and very respectful, it never got less humiliating.

When I first joined Victoria’s Secret in 2019, it still had the allure of being one of the world’s top brands and was regarded as the epitome of sexiness. The brand’s models, known as “VS angels”, were part of a certain beauty standard: they were thin, tall, the majority of them were white and all of them were cisgender. The brand’s annual fashion show was just as culturally relevant as the Met Gala. In 2012 – the year the London flagship opened – Barbara Palvin, Cara Delevingne and Miranda Kerr all walked down the VS catwalk in New York wearing Swarovski wings and million-dollar “fantasy” bras, while Rihanna, Bruno Mars and Justin Bieber gave live performances.

But things started to come crashing down around the time I worked there. In 2019, the brand axed its infamous fashion show after its former marketing chief, Ed Razek, controversially said he did not want transgender models in the show. Victoria’s Secret has since become embroiled in several scandals relating to inclusivity, body image and ethics. Razek was accused of multiple incidents of inappropriate contact with models, which is something he denied at the time. It also didn’t bode well when Les Wexner, the founder of L Brands – Victoria’s Secret owner – was connected to financier Jeffrey Epstein, who was charged with sex trafficking (some of Epstein’s victims came forward saying that he used his connection to Victoria’s Secret to coerce them into being alone with him – Wexner has said he was never aware of this).

After being marred by controversy, Victoria’s Secret has tried and failed to regain cultural relevance amid declining sales. This week, they’ve dramatically gone back on their “feminist” rebrand when the company told investors about Plan B: “sexiness can be inclusive”. The brand has continually failed to get in touch with the modern woman without patronising them or appearing too performative, especially given its track record promoting exclusivity over inclusivity. Perhaps this shows that the brand is better off targeting men who are looking for sexy gifts for their partners.

That’s fitting, since the idea of Victoria’s Secret was inspired by a man’s uncomfortable experience when lingerie shopping for his wife. Roy Raymond, an American businessman, decided in 1977 that he would create an underwear shop that was targeted at men. At the time, it was pretty ingenious. The name “Victoria” was chosen to evoke an element of British respectability associated with the Victorian era. But her secrets… well, you’d have to come inside to find out.

The brand was taken over by Wexner’s company in 1982 and transformed into a retail empire. The consumer focus was shifted onto women rather than men. By the Nineties, Victoria’s Secret had become the largest retailer in the US, with 350 national stores. The expansion elsewhere was inevitable.

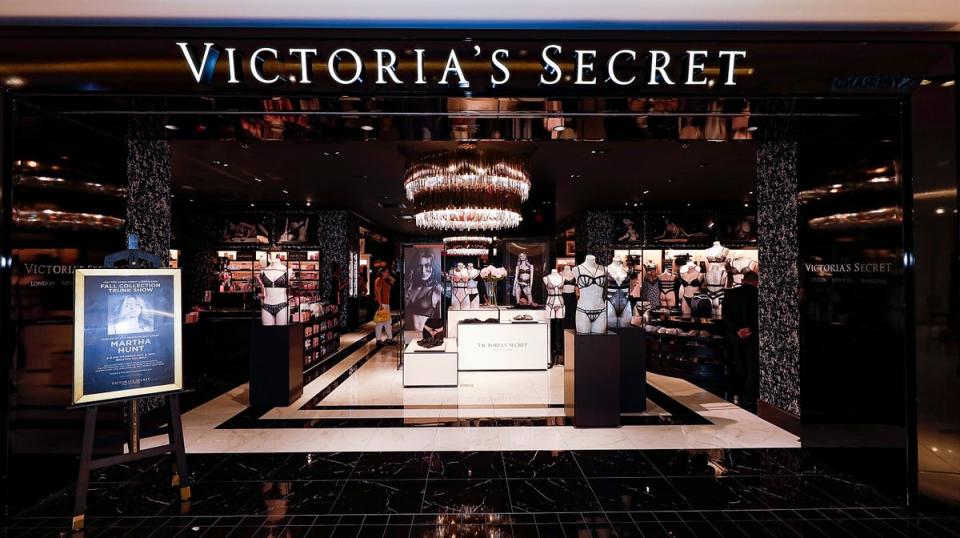

The London flagship store, my former place of work, is a 40,000-square-foot lingerie mecca that takes over 111-115 Bond Street. It was a carbon copy of its American counterparts: dimly lit rooms with striped wallpaper and matching marble floors, black shiny interiors and gargantuan chandeliers. There was, of course, the sweet sickly stench of Bombshell, the brand’s staple Eau de Parfum, mixed in a plume of the bestselling Bare Vanilla body mist that smelt just as sugary.

For a while, it felt like a cool job. I felt a bizarre sense of pride telling my University friends it was where I worked, rather than some dingy bar. Plus, I was chuffed when I left the store most weeks with A3-sized bags full of discounted lingerie.

There were a few rules and Americanisms we had to learn at the UK flagship. Knickers weren’t knickers; they were panties (folding them for display on “panty bar” was the bane of my existence on Sunday evenings). We wore tape measures around our necks for dramatic effect. Also, in another adoption of American retail habits, I had to discreetly inform each customer of my name so they could give feedback on how I did when they arrived at “cash wrap” – AKA the till.

There are probably some myths about the job I should debunk, too. We didn’t walk around in our underwear like in the 1998 film Enemy of the State, when Will Smith makes a blunder guessing his partner’s bra size. But that didn’t mean we weren’t wearing the product. Coincidentally, the exposed lingerie fashion trend was taking hold, so we’d happily wear lingerie under sheer tops or style bras – tastefully, may I add – underneath risque blazers.

I was on the receiving end of some baffling conversations. We know by now that some male customers didn’t know their partner’s bra size. In the event that the aforementioned “is she bigger than me?” tactic didn’t work, some customers would resort to showing me pictures of the lucky gift recipient. Once, to my horror, I was shown a nude photo of a customer’s much younger girlfriend. I also like to think I developed some diplomacy tactics when – as happened often – heterosexual couples would disagree on the style of underwear they wanted to buy.

Despite all the changes, U-turns and identity crises the brand has faced, though, one thing has remained the same: the panties at the Bond Street store are still neatly folded. Recently, I stepped back into Victoria’s Secret for the first time since I left and stared at that panty bar, thinking about those hours spent perfecting my folding technique. I left quickly, but not quick enough, the stench of Bombshell had already absorbed into my hair.