Let's raise a glass to Bill Kenwright, one of theatre's great risk-takers

The London theatre community was deeply saddened this week by the death of the bigshot producer Bill Kenwright. A titan on the West End and beyond, over his 50-odd year career as an impresario, he produced more than 500 projects including the recent hit My Son’s a Queer (But What Can You Do?), now heading to Broadway, the first big touring revival of West Side Story in 1972 and the 2000 production of Long Day’s Journey into Night starring Jessica Lange and Charles Dance.

But Kenwright was probably best known (except among football fans, because he was Chairman of Everton FC) for being the man who took Blood Brothers to Broadway.

He wasn’t even the original producer on the show when it premiered on the West End in 1983 — it did well, and earned an Olivier Award, but didn’t last long. Kenwright loved it though, and five years later he restaged it, alongside Bob Swash who had originated it, at the Albery (now the Noel Coward), where it ran for three years before transferring to the Phoenix. It closed there in 2012 after a record run of 21 years.

Despite everyone telling him he was mad, for the Broadway run, he coaxed Petula Clark out of retirement and cast David and Shaun Cassidy as her sons. The reviews were terrible. It was a hit, earning it the moniker “the miracle of Broadway”. The show has been touring more or less continuously since.

An inveterate gambler in his early days (you could argue he never stopped, creating large-scale musicals being a uniquely precarious business), Kenwright was above all a risk-taker. His loss this week is deeply sad for the community and his beloved family, but it struck me too that it came alongside a raft of announcements for new shows for 2024 that, on the face of it, feel a bit safe.

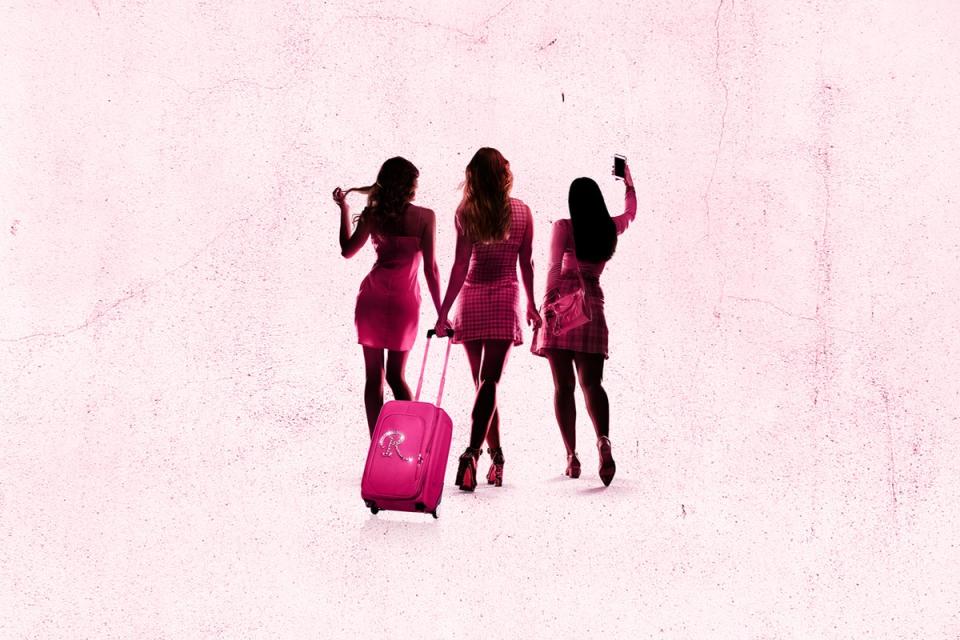

Stratospherically expensive, sure, but still pretty safe bets. Mean Girls the Musical, for example — a transfer from Broadway that was going great guns until it was closed by the pandemic after 833 performances — and based on a wildly popular film. The Devil Wears Prada too, already a meme-inducing camp-fest even before it was turned into a musical (though by all accounts, it needed a lot of work after a universally poor reception at its first try-out in Chicago).

And of course Kenwright himself got in on the act, with Heathers, and his forthcoming musical version of the 1999 movie Cruel Intentions (featuring familiar music from the likes of Britney Spears, Boyz II Men, Christina Aguilera, TLC, The Verve, *NSYNC, R.E.M and others), coming in January. In Birmingham there’ll soon be a stage adaptation of Withnail & I, which makes perfect sense, and of course Stranger Things: The First Shadow, coming to the Phoenix Theatre as soon as next month.

Then there’s The Hunger Games, coming to the West End next autumn for its global premiere. An adaptation by Irish writer Conor McPherson, it will roll in together the first novel in Suzanne Collins’s massive YA dystopia trilogy (more than 100m copies sold) and the film based on it (close to $700m on an investment of $78m for the first movie alone). I think it’s safe to say there’s an audience.

None of that is to say that it shouldn’t be done. Frankly it might be the thing that keeps theatre going for the next few years — audiences are risk averse in a cost of living crisis, and more inclined to spend their money on something they’re already pretty sure they’re going to enjoy. And I’m excited and certainly curious to see most of these shows (particularly how they’re going to pull off The Hunger Games, a series that relies largely on running around a forest and shooting people with a bow and arrow).

But what I hope is that in addition to these, West End producers can screw their courage to the sticking place, channel the spirit of Kenwright’s most seemingly insane decisions, and take big creative risks too, on quality new writing and experimentation that deserves an audience but doesn’t seem like an obvious 'hit'.

People are doing it. The impresario Nica Burns, for example, not only put her money into the first new-build West End theatre and restaurant in 50 years, @sohoplace, she’s been tirelessly developing new work in there too. The theatre’s current production is a new musical based on the memoir of Henry Fraser, a promising rugby player whose life changed in an instant when a diving accident rendered him tetraplegic. It features a flying wheelchair, with the actor Ed Larkin — the first wheelchair user to lead a West End musical — in it. The least interesting thing that’s been on at @sohoplace has been a stage adaptation of the much-loved film Brokeback Mountain, which failed to ignite.

And I saw Cabaret at the Kit Kat Club for the second time recently, with Rebecca Lucy Taylor (AKA Self Esteem) as Sally Bowles and Jake Sheers as the Emcee, and was struck by what a colossal risk that was in the first place, even with the superstar opening casting of Jessie Buckley and Eddie Redmayne in those roles (Redmayne is returning for the opening of the Broadway production, for which he also serves as a producer).

The gamble of turning that theatre upside down and inside out to create a whole experience, straight out of a global pandemic, when in reality it’s quite a weird, thin show, and the beating heart of it is not the dysfunctional romance between Sally and the writer Cliff, but actually the secondary storyline about the tentative affection between a Jewish grocer and a Gentile landlady as the Nazis rise to power, frankly beggars belief.

You’d have said they were bonkers. Just as everyone said Bill Kenwright was bonkers to bring back Blood Brothers. And yet. Sure, a lot of this stuff won’t work, won’t break even, won’t find its audience no matter how much it deserves to. But that’s showbiz. And I’m grateful for the chance to take my own risk and see it. So let’s raise a glass to Bill, and all those like him.

What the Culture Editor did this week

Clyde's, Donmar Warehouse

Though not as consequential a work as writer Lynn Nottage's Pulitzer Prize and Evening Standard Theatre Award-winning play Sweat, this sequel of sorts is still a joy in the hands of director Lynette Linton, and her warm, expressive ensemble cast. Set in a Pennsylvania truck stop kitchen that employs ex-cons, it explores redemption and grace through the medium of the perfect sandwich. Lovely. Listen to our review of Clyde's on the Standard Theatre Podcast this Sunday; we have a new episode every week.

Lyonesse, Harold Pinter Theatre

Not even the stunt casting of Kristen Scott Thomas and Lily James in the leading roles can help this implausible, hectoring, thinly drawn and poorly structured mess of a play. Its five fine actors gamely give it their all, but they've got almost nothing to work with and not a shred of credibility as characters. I'm cross about it. You'll hear about that on the podcast next week, so that's something to look forward to.