Kids pics should stay in a photo album – not on social media

At the time of me writing this article, my iCloud library stands at a cool 43,357 photos. I estimate it will probably go up by about 20 or 30 by the time you end up reading this. It’s my daughter’s karate grading today, for example, so hopefully I’ll take a few pics of her with her new belt. My son is also going to a pirate-themed birthday party later, so I imagine I’ll take a few shots of him and his swashbuckling friends.

I couldn’t live without pictures of my children. They go through so many developmental stages and subtly mutate at such a rapid speed that it’s hard for your memory to latch on to any of it, especially in the first 10 years. Looking back is a very active part of being a parent. But, quite clearly, there’s something wrong about having more pictures than every gallery in London combined of just two kids.

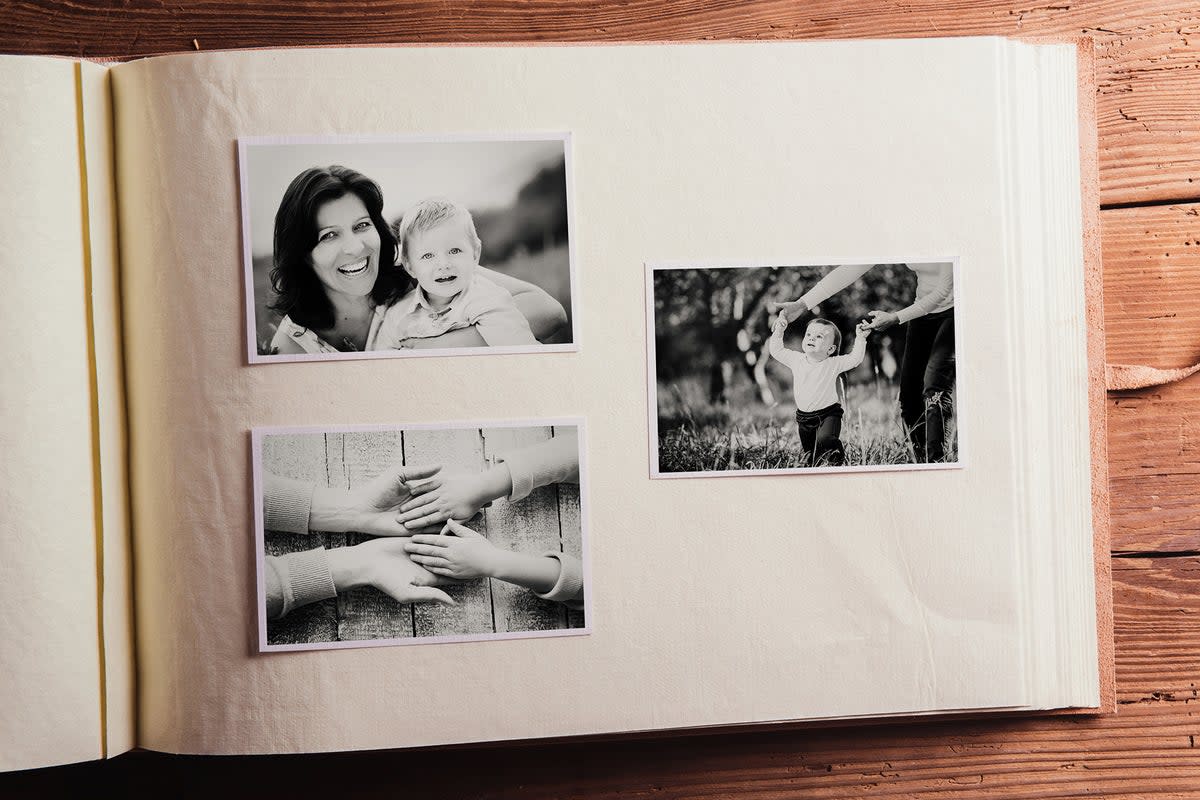

That’s why, in my slow and shameless evolution from a young man to an old man, all I want for Christmas this year is a modest, old-fashioned photo album with maybe 80 or so pictures of my kids in it. Everything else can vanish.

It might seem quaint to choose to laboriously print and stick a load of pictures into an album, given how easily and socially acceptable it is to build a virtual photo album by posting to apps like Facebook or Instagram. But I think we’re at a turning point here. More and more people are shying away from posting their children on social media, for a plethora of reasons. At the most extreme end, we’re on the cusp of learning more and more about the effects of using children as online content – as the first generation of influencer children begins to grow up and start telling their stories first hand. On platforms like TikTok, as well as in books like Stephanie McNeal’s Swipe Up For More! Inside the Unfiltered Lives of Influencers, we can hear the emotional burdens of having to smile for the camera as a way to pay the bills, or to dress a certain way to make clients happy. When kids finally read the vile comments their posts elicited (commonly reflecting a feeling that users preferred it when the kids were younger and cuter), it all points to how toxic online “sharenting” can become.

To reiterate, these are extremes, yet the same principles apply even if you’re not an overzealous influencer. When a parent posts pictures without their child’s permission, they are riding roughshod over their kid’s right to privacy. The fact that you’re their legal guardian doesn’t give you any legal exemption to do what you like with their image. In practice, it’s obviously very hard for a child to assert their rights without access to, say, a lawyer – which is why the NSPCC urges parents to ask for a child’s permission before posting. This is challenging, though, as it involves having to explain what social media is. Thus, never has the maxim “If in doubt, don’t” seemed more reasonable.

The parenting experience can often feel, especially around infancy, like being in a tiny cult, wherein your child is a fringe, obscure deity that only a small number of people (parents, relatives) intensely worship. By contrast, social media is a punchy, blunt place that almost goads you into being negative at times. It’s why I don’t wish to post pictures of my kids online, lest they somehow provoke the ire of someone either having a bad day or someone with a malign intent. Social media followings tend to be impossibly random, and I don’t think it’s reasonable for someone you met in the smoking section of a club once at 3am to have the same levels of enthusiasm for your mewling DNA clone as your fellow cult members.

Even though we know that hoarding is unhealthy, who among us can deny that they mercilessly hoard digital photos nowadays? We do it aimlessly because there doesn’t seem to be a downside, even though the carbon footprint of storage (from cooling heating servers) is a ticking environmental timebomb most of us pretend we can’t hear.

Even less discussed, though, is what kids of the cloud age will make of a digital inheritance of perhaps 30,000 pictures of themselves when they reach adulthood? It’s not impossible to imagine some becoming almost obsessively consumed by it, maybe via sheer narcissism. Others could be driven mad by trying to discern some meaning from it all, as if endless dives into a bottomless archive could patch any holes in your adult psyche.

By contrast, it’s pretty hard to become obsessive over the incredibly humble and ingeniously drab photo album. Most pre-digital kids groaned when the albums would come out at family occasions, and with good reason: they were naff and deeply cringe, they were about going back and reminiscing when you just wanted to live and leap into the future. A child’s life should be lived fast with no baggage, not chronicled minute by minute. They should make memories that exist in the cerebral cortex, not in jpegs. A vast well of content is not in anyone’s interest, least of all a parent who one day is just going to want to remember the good stuff. The nerves she felt before that karate grading. The superhuman strength he employed to stop himself face-planting into his swashbuckling friend’s birthday cake.