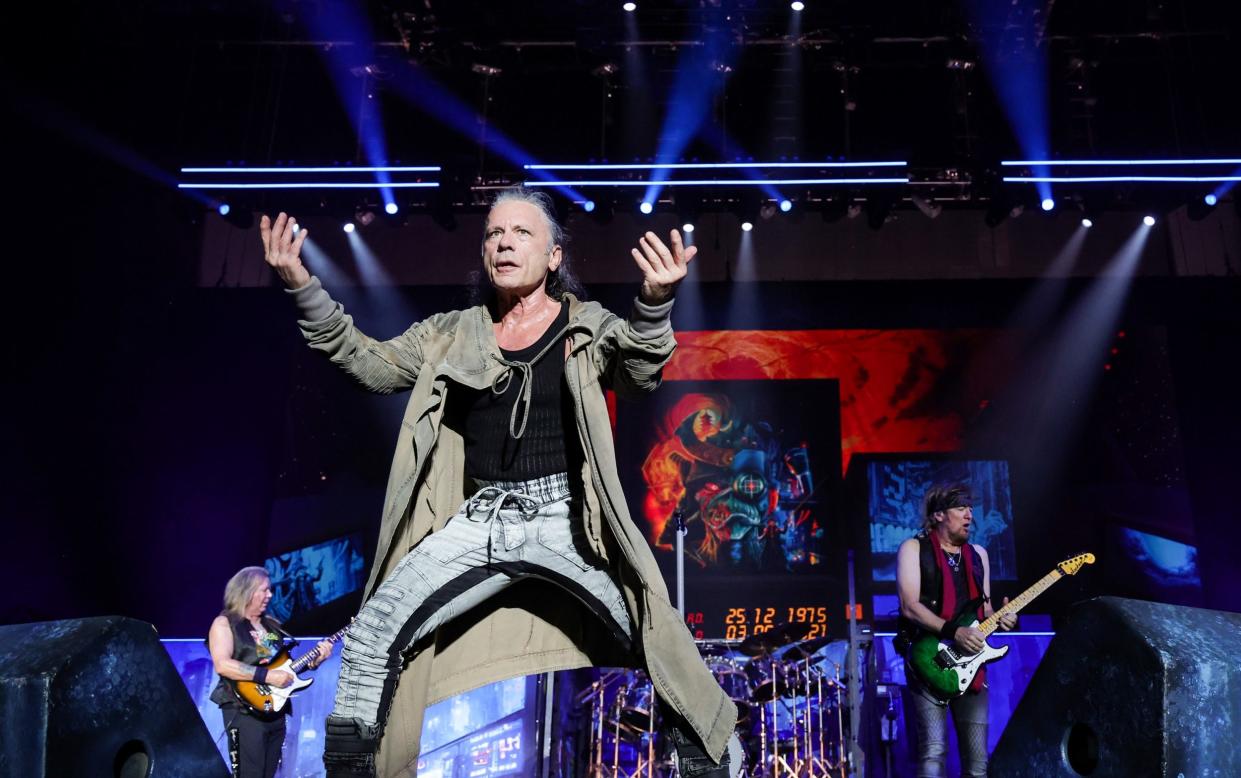

Iron Maiden’s Bruce Dickinson: ‘None of the big heavy metal bands are anything other than bourgeois’

It’s easy to get lost in the legend of Bruce Dickinson. For upwards of four decades, the 65-year-old has fronted Iron Maiden, the most successful and beloved name in British metal. His near-operatic voice helped thrust the band’s breakthrough album, The Number of the Beast, to number one in the UK charts. He beat throat cancer in 2015, and his hobbies have included competing in international fencing tournaments or piloting his bandmates across the world in their customised jumbo jet.

At Paris’s Gare du Nord station, I see him ambling towards me with an outstretched palm and wide grin; his long grey hair bundled up in a flat cap, an England rugby top beneath his leather jacket. It is bizarre to see this legend of British music – usually on stage wearing a Crimean War uniform, or mucking about next to Iron Maiden’s 10ft-tall zombie mascot Eddie – without any kind of entourage, coming to pick up a journalist on his own.

He takes us to a cafe across the street, where he sits, huddled over a table, chatting happily for almost three hours. Dickinson and I are meeting in Paris because this is where he lives now. Well, sort of.

The singer – along with his wife, French journalist Leana Dolci, whom he married late last year – divides his downtime between here and the UK, where his three children still live. And, even then, downtime is still a rarity for him.

Not only is the Maiden machine still barrelling forth (tours of Oceania and the Americas are planned for later in the year), Dickinson will soon be releasing The Mandrake Project – his first solo album in 19 years and seventh overall. The singer’s voice still soars over grandiose metal, yet – thanks to the work of guitarist and producer Roy Z – the music is darker and heavier than his work with Iron Maiden.

The concept is bonkers: William Blake, sex rituals, a misanthropic academic called Dr Necropolis and experiments in resurrection. The narrative will be more fully explored by 12 tie-in comics, released quarterly.

“I read comics when I was a kid – up in Sheffield, as a spotty adolescent,” Dickinson tells me, smiling. “I was a big fan of the Human Torch and the Fantastic Four, but I never got Superman. It was like, ‘Oh, come on! Why don’t you take Lois Lane behind the bikesheds and give her one?.’” Even at 65, he still has the bawdy humour and mischievous grin of a schoolboy.

Dickinson clearly isn’t shy with his opinions, which we soon trace all the way back to his upbringing. While the musician was growing up in Worksop, Nottinghamshire, his father (an army mechanic) and his paternal grandfather (a coal miner) had “some very scathing opinions about just about everything”. He remembers having “these arguments with my dad that would go on for hours. When I beat him at chess at seven or eight years old, we never played chess again”.

Dickinson’s mother and father were still teenagers when they had their son, so he spent his formative years largely with his grandparents. It was through them – or, more specifically, dancing to Chubby Checker in their living room aged four – that he truly discovered music and performing.

After he spent his early education hopping around schools in Sheffield, they eventually sent the youngster to public school.

“I developed my own sort of mini-terrorist organisation,” Dickinson laughs. “I sent two tons of horses--t to my housemaster. I was beaten but it was absolutely worth it. Six strokes of a cane and your a--e would bleed, but it was definitely worth it, seeing two tons of steaming horses--t on the front steps of this ornate Georgian facade and thinking, ‘I did that’.”

Have metalheads ever falsely perceived him as a “posh boy” for his public school education? “No,” Dickinson says, laughing again. “I wasn’t a posh lad at all, which is why [my classmates] kicked the s--t out of me at school. I thought they were a bunch of posh c---s, and I told them that.”

He adds that heavy metal being working class is a stereotype, because, “with the exception of Black Sabbath, probably, none of the big heavy metal bands are anything other than bourgeois”.

!['I wasn’t a posh lad at all, which is why [my classmates] kicked the s--t out of me at school'](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/8y8X3Cr9dZdZJbd7IcD.jw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTk1Ng--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/the_telegraph_818/7f4ebd4127f666e9a60c3e700717f74f)

After moving to London for university, and with a love of Deep Purple and Arthur Brown, Dickinson got swept up in the new wave of British Heavy Metal. He first joined pub-rockers Samson, then Maiden in 1981. The band topped the UK album charts for the first time the following year with The Number of the Beast, their third album overall. Across the pond, the material’s satanic themes inspired protests from Christian fundamentalists and mass burnings of LPs.

“We never aimed to do anything like that,” says Dickinson. “[It was] primarily a phenomenon of the USA, where they have an underdeveloped sense of irony. We just thought, ‘People want to buy our records and burn them? Go ahead!’”

Iron Maiden would make two more UK number one albums with Dickinson up front: 1988’s Seventh Son of a Seventh Son and 1992’s Fear of the Dark. But in 1993 the singer surprised fans by stepping down, expressing a longing to fully pursue his own music.

“Rod [Smallwood, Iron Maiden’s manager] was a very powerful figure,” says Dickinson. “And a lot of the band felt like we were working for him. It was the father and his wonderful sons. Part of me was rebelling against that.”

Dickinson had first gone solo three years prior with 1990 album Tattooed Millionaire, which, on form for the singer, was material that bore his thoughts on its sleeve, uncensored. The title track’s lyrics savaged the hedonism and womanising of bands such as Mötley Crüe in the then-exploding glam metal movement. “There’s a point at which [that kind of behaviour] is fun,” Dickinson says. “But there’s a point where it’s so f---ing empty. It’s just vacuous.”

He returned to Iron Maiden in 1999, but also kept his own, independent vocations. He took a full-time job as an airline pilot at Astraeus from 2002 to 2011 and used his unpaid leave to tour with the band, continuing a passion for planes he first picked up from his great-uncle in Worksop. “He had been in the Royal Air Force in the war, as a flight engineer,” explains Dickinson.

“I flew Michael Heseltine and Max Hastings to Murmansk, in Russia, for some government thing,” he continues. “The Russians threatened to shoot us down, so I had to land in Finland. I was the first aeroplane to land in Sierra Leone after the civil war.”

Alongside being a pilot, the singer is also a championship-winning fencer (a hobby he started at public school), an author (his autobiography came out in 2017) and a screenwriter (he wrote the script for the 2008 cult horror film Chemical Wedding). He’s no longer allowed to fly commercial jets due to his age, but is unfazed: his attitude towards the extracurriculars, he claims, changed after beating cancer.

“I realised, with the best will in the world, it’s great that I can be an airline pilot, but thousands of people can do that,” he says. “Creating things is different. Being the lead singer of Iron Maiden is like Highlander: there can be only one.”

Following a lifetime of rebellion, 40-plus years on metal’s frontlines and the making of seven solo albums, what does this man have left to say with his music? That schoolboy grin returns. “I’ll tell you tomorrow.”

For now, Dickinson has fencing practice to attend. We part with a handshake back at Gare du Nord and, by the time I look over my shoulder, Iron Maiden’s frontman has vanished into the crowd.

The Mandrake Project is released March 1