The House of Beckham by Tom Bower review: Posh and Becks exposé won’t spice up your life

After a series of bombshell books about the Windsors, writer Tom Bower has turned his gaze to Britain’s other royal family: the Beckhams. In the years since they married on matching thrones in 1999, footballer David and former Spice Girl Victoria have become – in the eyes of the public at least – less of a couple than a shiny, impenetrable mega-brand.

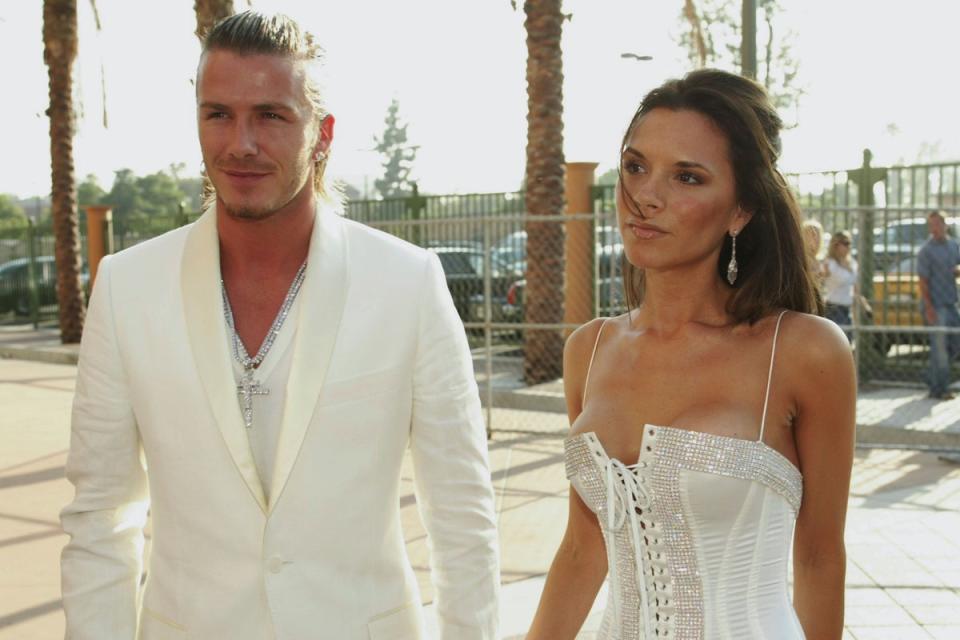

Together, the former Manchester United wonderboy and Posh Spice are something much greater than the sum of their parts. They may no longer dress in his and hers outfits, but their image – propagated in golden Instagram despatches from their country residence in the Cotswolds and smiling all-family snaps from the front row of Victoria’s fashion shows – is now generally one of carefully curated, photogenic harmony. Their names adorn everything from high-end clothes to aftershave, glasses to whiskey. And yet, over the course of their almost 25-year marriage, there have always been rumblings that all is not quite as it seems behind the scenes at House Beckham, and that the couple are, as Bower puts it in his book, “consummate actors” merely play-acting to project what their public wants from them.

So can Bower’s book, salaciously subtitled “Money, Sex and Power”, actually pierce the pair’s golden armour and dismantle the Beckham machine? That’s arguably a far bigger task than putting the royals under the microscope, given that the family’s PR operation is so staggeringly slick. The recent Netflix documentary, Beckham, was the sort of puff piece that strenuously pretends not to be a puff piece. It offered stage-managed insight and endearing off-duty snippets (like the much-memed moment when Victoria described her working-class background, until David pressed her to reveal that her father drove her to school in a Rolls-Royce) and briefly alluded to a few major headlines – like Beckham’s alleged affair with his one-time PA Rebecca Loos – while tactfully brushing over other rumours. If anything, it burnished their reputation rather than exploring or challenging it.

The House of Beckham certainly strains to be explosive, but ends up falling short: the overall feel is underwhelming, like delving into a Wikipedia recap that re-treads old territory rather than digging up genuinely shocking dirt. Many of the quotes are recognisable from old interviews and the allegations are from old newspaper reports, now forgotten but still available in the dark recesses of the internet. All this means that David and Victoria seem no more real to the reader than they did before embarking on this overly long tome. In The House of Beckham, Bower seems content to just rehash the less flattering stereotypes of the couple that have always existed in the media: that David is airheaded, that Victoria is thin and miserable, and that they are both vain and money-obsessed. Although the book runs to nearly 400 pages, the pair are sketched out with all the nuance of a tabloid column.

Bower’s overarching argument is that the couple’s marriage has, at times, been little more than a mutually beneficial business arrangement – that at times, “their financial fate depended on maintaining the charade” (again, this hardly feels like a novel thesis). He kicks things off at Glastonbury Festival in 2017, when the couple apparently became embroiled in a “ferocious argument” after David failed to pick up Victoria’s phone calls while living it up in the VIP area (she has, we’re told, a real disdain for his “dreggy” party pals). The couple’s spokesperson, meanwhile, tells the media that they “had a great night”. This episode comes to illustrate how, in the Beckhams’ world at least, two versions of reality can apparently exist at once.

After rehashing the Loos debacle – Bower has a strange habit of referring to the media storm surrounding her as “the darkness” – The House of Beckham then falls into a largely chronological retelling of the Beckhams’ relationship (there’s little here about their lives before meeting each other). As a new couple, “they glowed with glamour, just like the late Princess Diana”, and the tabloids decided to treat them with the attention they’d previously lavished on actual royalty. They provided the fuel for the “Posh and Becks” machine, and made some serious money in the process: putting the couple on the front page would increase The Sun’s circulation by 4 per cent.

But by the time David made his move to Madrid – having apparently enraged Sir Alex Ferguson by arriving for training at Old Trafford wearing an Alice band in his hair – the coverage is less glowing. Bower takes us through various allegations of infidelity (ones which don’t seem to have stuck in our collective imagination like the Loos incident) and presents the pair as going through the motions, unhappy behind the scenes. A repetitive pattern emerges in which the couple are hit by scandal, seemingly drift apart then emerge in a triumphant display of PDA; they also seem to complain about press coverage while engaging in an intricate dance of favour with their chosen members of the media.

It’s not all salacious drama, though. We learn that on a shoot for one of his first ad campaigns, David was told he could choose whatever food he wanted – then requested a Hawaiian pizza from Pizza Express. Posh, meanwhile, was offered a role in Starlight Express after the Spice Girls parted ways. After meeting the couple for the first time, Prince Charles reportedly pondered: “Why do these people never wear socks?” There are some rather banal details about Beckham’s alleged relationship with Loos, too. Bower claims that a “turning point” in their rumoured fling came after the footballer failed to tip staff at the Hard Rock Cafe in Madrid. When Loos returned the following day, a waitress gave her a note directed at Beckham, explaining how she and her colleagues relied on tips to make a living. Loos, Bower says, was disturbed by “Beckham’s double standards” and became “angry”.

Bower repeatedly seems to suggest a certain stinginess on the part of this very wealthy couple. Perhaps more contentious are the claims that he makes about David’s “opaque” and “unusually complex” finances. “Legally avoiding British taxes appealed to Beckham,” Bower writes, before claiming that “as a non-dom in Spain” while playing for Real Madrid, “he was not paying British taxes on income earned outside Britain” and “was not paying national insurance. The genius of it was that no one in Britain realised that Beckham had become a tax exile.” He even suggests that tax arrangements may have been a defining factor in some of the footballer’s later career decisions, allegedly making gigs in America and France more appealing than returning to his home country to play for a London side (a spokesperson for Beckham told the author that he was taxed fully on all his income earned in Spain and elsewhere). None of this, we’re told, went down well with the Honours Committee in charge of dishing out knighthoods.

The book’s more interesting revelations, though, are mired in repetition and over-familiar details, diminishing their impact. There’s nothing here that really resembles a smoking gun, just anecdotes that might trigger a remembrance of some long-buried celeb gossip. There must be plenty of material out there for a truly enlightening look at the Beckhams’ story, but this isn’t it. The custodians of Brand Beckham can sleep easy – Bower’s book seems unlikely to topple their empire.

‘The House of Beckham’ by Tom Bower is published by HarperCollins, £22