How Hollywood’s Most-Feared AI Video Tool Works — and What Filmmakers May Worry About

As generative artificial intelligence marches on the entertainment industry, Hollywood is taking stock of the tech and its potential to be incorporated into the filmmaking process. No tool has piqued the town’s interest more than OpenAI’s Sora, which was unveiled in February as capable of creating hyperrealistic clips in response to a text prompt of just a couple of sentences. In recent days, the Sam Altman-led firm released a series of videos from beta testers who are providing feedback to improve the tech. The Hollywood Reporter spoke with some of those Sora testers about what it can, and can’t, really do.

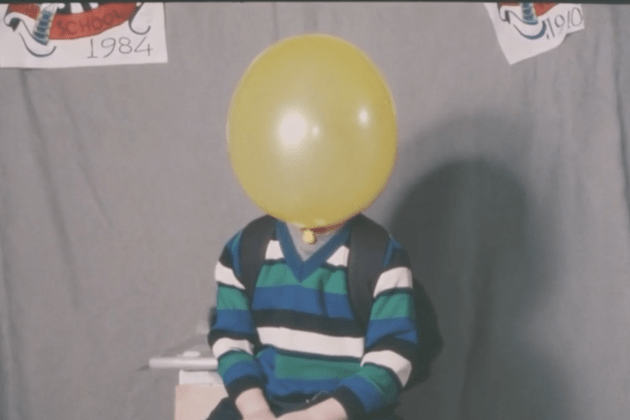

Sora was made available to the team at Shy Kids, a Toronto-based production company composed of Walter Woodman, Sidney Leeder and Patrick Cederberg, who’ve collaborated on projects with HBO, Disney and Netflix in feature films such as Blackberry, Therapy Dogs and Nerve. With the tool, the trio created Air Head, a surrealist short film about a man with a balloon for a head.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

Hayao Miyazaki's 'The Boy and the Heron' Smashes Box Office Record in China

Shakira Feels She "Used to Overdo" Her Vocal Yodel When Singing

Woodman says he considers Sora another tool in his arsenal, similar to Adobe After Effects or Premiere. “It’s something where you bring your energy and your talents and you work with it to make something,” he explains. “There’s a lot of hot air about just how powerful this is and how this is going to replace everything and how we don’t need to do anything. That’s really undervaluing what a story is and what the components of a story are and what the role of storytellers is.”

Still, the potential is undeniable. “For me, the most exciting thing is the idea of being able to bring your vision to life a bit quicker, to better demonstrate it and then hopefully get past some of the hurdles and the prohibitive walls of gatekeeping of the film industry,” Cederberg says.

Leeder stresses, “It has the ability to really democratize the film industry.”

A caveat remains: Widespread adoption of AI tools in the moviemaking process will depend largely on how courts land on novel legal issues raised by the tech. Among the few considerations holding back further deployment of AI is the specter of a court ruling that the use of copyrighted materials to train AI systems constitutes copyright infringement. Another factor is that AI-generated works are not eligible for copyright protection.

Notably, OpenAI doesn’t disclose the materials used to train its system. It no longer reveals the source of training data, attributing the decision to maintaining a competitive advantage over other companies. The firm has been sued by several authors accusing it of using their copyrighted books, the majority of which were downloaded from shadow library sites, according to several complaints against the company.

In an interview, the Shy Kids team elaborate to THR on their experience creating a short video primarily using Sora, potential use of generative AI tools in Hollywood and controversy associated with the tech.

Let’s get into some of the technical capabilities of Sora. What can it do?

Woodman: It can generate text to video up to a minute long. Most of the time, we were making things that were closer to 20 seconds long. It can generate some pretty interesting images.

Cederberg: It has the same pitfalls as a lot of generative AI in that consistency is difficult. Control is difficult, which as creatives, I mean, you want control. That was our general feedback to the researchers: More control would be great, because we want to try to tell a story using a consistent character from shot to shot and from generation to generation. Part of that is the reason why we ended up going with the guy with the balloon for a head, because it’s a little bit easier to tell that that’s the same character from shot to shot compared to someone whose face is changing. That’s obviously an issue with it, but it’s all early days right now.

Tell me about the making of Air Head. What did the workflow look like?

Woodman: We dusted off our old folder of ideas that we have, that I think every filmmaker has, of, “Here’s a character I want to see,” or, “Here’s a situation I want to see.” To be honest, a lot of those didn’t work. They were pretty weird and crummy and awkward. And then we stumbled upon a guy with a balloon for his head, which was just a weird drawing I had in one of my moleskin notebooks. When we started to generate it, it looked really cool and really good. From there we wrote a script, and after that we began generating images together. It was really interesting because Sid or Pat would generate something that would kind of lead us down a different path and lead us down a different avenue. Once we had enough footage, we began to edit it down into a manageable chunk. We began to animate. Pat was saying that I think probably around 50 percent of the shots have treatment on them. All of them have a sort of look and a color grade applied to them to make it all look consistent. We animated and rotoscoped and made sure that everything was cohesive and sort of together. And then we added sound design. We recorded the V.O., which is Pat doing the voiceover, and we added music, which was a song that we had made.

What did the process look like to get Sora to return your main figure in Air Head? And how many times did you have to prompt Sora to get a figure you were happy with?

Cederberg: When you put in “Man with a balloon for his head” and the machine has a little dream about what that can look like, a lot of times we’d find that it would give them a face and would draw with a marker, like little smiley face on it. We were like, “Not quite it.” So we’d write in, “Man with a balloon with no face on it.” And then of course the machine would see the word face and go, “Oh, do they want a face again?” So then we would get a balloon with a human inside of the latex, and that was kind of horrifying in its own way. Ultimately, it’s like with any prompting in general; it’s about homing in the language of trying to figure out what can get the machine to do what you want it to do.

Leeder: I think it also got used to that. I feel like we put in so many, “Give us a man with a balloon for a head” prompts in that it was like, “OK, I get it.”

Woodman: I would love to actually know how many, but I would say it would be in the hundreds. That’s the funny thing: You read the Twitter comments and they’re like, “Oh my God, this was so easy.” If you only knew how many psychotic balloon-faced things I’ve seen, you would know that it wasn’t just, “Here you go, here’s the movie.” It still requires tons of work and tons of molding.

Cederberg: And as Walter was speaking to before about the VFX stuff, a lot of times we would find a shot that had the perfect composition for us, but the balloon was the wrong color. So we’d have to go in and do some rotoscoping and recoloring. Some shots, like the one where he’s running through the park and chasing his balloon as a headless body, it wouldn’t generate a headless figure, so we had to go in and roto the head out, do a little VFX work to try to make that look the way we need to. There are a lot of human hands touching this thing to try to get it to look semi-consistent to get it to where we wanted it to be.

How do you control the composition of the shots?

Woodman: It’s still going to film school. We would try to say stuff like, “Dolly in or Boom Up” and A, most people on a film set can’t agree what those terms mean. But B, I would say that it definitely was unsure. So in some ways you had to sort of trick it into doing something that you wanted it to do. I would say the other thing, there was some things that we found would work. So for example, we love Darren Aronofsky. We think of The Wrestler and Black Swan. He always has those beautiful shots following people from behind. And we found that that was something that was working quite well. And we knew that if we got a couple of those that they would be able to cut together because they would look quite similar if you have this from-behind shot style. But in terms of composition, it was quite hard. And I would say that as a filmmaker, that was one of the most challenging things because you really want to go just stand over there like you would. But I think over time, that will get better and that will get more isolated, and you’ll be able to be more fine-tuned with that. However, that was, again, some of the first things we told the researchers: We need to take this thing to film school. It needs to know the difference between a zoom and a dolly and a wide shot and a close-up and a 35 and a 70 millimeter lens. So it was difficult. And to get something that kind of functioned took a lot of trial and error.

In the prompt, are you putting it in wide shot or tracking shot? Does it have that capability, or do you just have to toy around a bit?

Leeder: We’ve been testing that ourselves. It does know wide. You can phrase that a few different ways. I feel like at first we were saying, “The entire park is in frame,” or you try to phrase it different ways to see what stuck and what got you to resolve. Now I do think a wide shot works. Or even saying it was shot on this type of film or shot on a phone or old VHS footage. It does seem to understand that quite well.

So one thing you said that kind of struck me is Sora’s ability to make things that are totally surreal. Can you elaborate on that?

Woodman: What’s really interesting to me is making things that don’t look like the world around us that create a sort of new world. And I think that that’s a really exciting place to be: a sort of surreal, new world where balloon people can go to cactus stores. I like that juxtaposition and that imagery. That’s cool. I also think that there’s a bunch of stuff that we made that looks totally cursed and weird, and I love that stuff. It’s like when you see weird limbs and cats with eight legs and stuff like that. It’s like Yorgos Lanthimos could only dream of these kooky, weird morphing things. And I think that actually those things are going to be kind of a new cool aesthetic to play with ,and how can we make these sort of demonic dream characters or beautiful dream characters? I think that’s going to be really interesting.

Cederberg: Air Head is surreal, but we wanted to keep it grounded, and we wanted to see how far we can push a realistic aesthetic with some surreal elements. And I think some of the other artists that were featured on the First Impressions blog have some examples where it pushes a little bit more into the weird and surreal and abstract. That stuff is very exciting.

I’d love to see the blooper reel for Air Head.

Cederberg: We would love to do something with the mountains of horrific Cronenberg-esque balloon freaks that exist.

Where do you see the role of AI tools like Sora in the future of the industry?

Woodman: We see it as a tool. I would liken it closer to something like After Effects or Premier. It’s something where you bring your energy and your talents and you work with the tool to make something. There’s a lot of hot air about just how powerful this is and how this is going to replace everything and we don’t need to do anything. That’s really undervaluing what a story is and what the components of a story are and what the role of storytellers is. I think it’s a very great tool, especially in the ideation phase. It’s going to allow people to make some really cool sizzles and pitch decks and things like that. And I also think it’s going to be really helpful in the editing stages. I think a lot of the times when you get to an edit, it’s kind of like, “What do we do? We have this great idea, but how do we explore this idea? We have all your footage already, how can we extend this or change this?” And I think that it’s going to really open up possibilities for those parts of the process to really expand and be more fluid than I think they’ve been in the past for some people. Others are going to go, “I don’t like it. I don’t want to use it at all.” I love Quentin Tarantino. I love Christopher Nolan. I think that they’re not going to change a single day in their life.

Cedeberg: For me, the most exciting thing is the idea of being able to bring your vision to life a bit quicker, to better demonstrate it and then hopefully get past some of the hurdles and the prohibitive walls of gatekeeping of the film industry. There’s plenty of great independent film right now, but to say that independent film is in a good place would be, I would say, naive and ignorant. And I think that the power for this to empower independent creators to gain access past these barriers that have been put up, is exciting.

Leeder: In our minds, every project requires a different set of ingredients. We’re still going to shoot things on film. We’re still going to make things in the traditional ways. Not every project will incorporate Sora, but there will be specific projects where Sora is incredibly helpful. It all depends. It’s an additional tool in our toolkit.

It sounds like you view this much as more as a complementary tool?

Cederberg: Yeah, having used it and as powerful as it is, I don’t think any of us at any point were like, “Oh great, we don’t have to work with people anymore.” That’s the heart of making something that is great: It’s working with human beings. It’s just how can this technology allow us and allow humans to elevate the humanity and allow us easier access to that humanity. It’s not something that can replace people. I feel like if more people have their hands on it, they’d realize that for themselves pretty quickly, too. It’s not a magic box that will suddenly make you Stanley Kubrick.

Woodman: You kind of need a brain and years of experience and taste and ability. I wish it did, but it doesn’t, and I don’t think it ever will.

Gen AI is obviously a hot button issue in Hollywood right now. What do you think about the possibility that Gen AI tools like Sora are going to lead to mass displacement in the industry?

Woodman: I would say that we feel for you. I understand feeling fear. Nobody wants to feel that they’re going to be replaced and no one wants to feel like something that they’ve worked so hard for is going to be completely undervalued and devalued. And our intention is never to do that. I think that there are moments where Sora is very appropriate and very helpful, and I think that there are moments where it won’t be very appropriate or very helpful.

What I am interested in is what happens when you give this technology to people in Bangladesh or Lagos, Nigeria. Let’s see what their stories are. I watch Nollywood films, and I’m extremely inspired by what they’re doing with very meager means. I think that artists always find a way to make things. And if they have access to these technologies, I wonder what those movies will be like. We’re underestimating how many more new filmmakers will get to be seen because their visions can come to life because they have the ability to make something that looks really interesting and really cool.

Leeder: It has the ability to really democratize the film industry. We’re an indie film production company. We’re often working with limited budgets. Like I said before, there’ll be some films that we still shoot traditionally and there will be other films where we will use Sora, and using Sora will mean that an idea that we wouldn’t be able to bring to life is able to come to life. It’s changing times.

Cederberg: There’s no denying that there’s a paradigm shift coming. All of us having used it, at no point did any of us say to each other, “Oh, thank God we don’t have to work with artists anymore.” We are part of a creative community here. We employ and work with artists all the time. That’s what art is: humanity. This is just another tool. I have more faith in culture and people than to assume that anybody would stand for losing the humanity in art.

What about the possibility that Gen AI tools like Sora may be built off the backs of copyrighted works from creators like yourself?

Woodman: This is an issue that it’s very important to us. We should pay people for their creativity and originality. What I would say is that I’m going to be very excited for when I can train Sora solely on the things that I’ve made, and then it can be far more tailor-made to what I need it for. You would have to talk to OpenAI about exactly where they’re using all of their training data. But the place that we are in right now is the experimentation phase. We’re just trying to see if we can use it to make something that we believe to be original and artistically valid.

Cederberg: I think that it’s an important conversation and one that right now, given that we are in the research phase and we’re just artists who have the ability to experiment with a new tool and as tech forward artists that excited us, we’re just excited to help develop the tech. But obviously as the scope opens up and it widens and whatever Sora turns into, that’s a conversation we’re going to be watching with attentive eyes as well, because we do believe artists should be protected, supported and compensated.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter