Government backs reduction in police response to mental health incidents despite safety warnings

Ministers are backing a potentially “dangerous” new model allowing police to reduce their response to mental health incidents after failing to formally assess the risk of harm or death.

Officials are monitoring any “adverse incomes” from the National Partnership Agreement, which will see police forces stop attending health calls unless there is a safety risk or a crime being committed.

Policing minister Chris Philp said a pilot by Humberside Police gave him confidence in national roll-out, which aims to “make sure that people suffering mental health crisis get a health response and not a police response”.

He told a press conference that one million hours of police time could be “freed up” for crime-fighting annually if all 39 English forces implement the agreement, although no official impact assessment has been done and it may take two years for deals to be struck in every area.

Mental health charities and experts have warned the plans could be “dangerous”, and a coroner raised the alarm following a woman’s suicide after police failed to respond to her disappearance.

Helen Findlay, 28, fled a mental health facility in east London in June 2020. Staff called the police, but neither Met officers nor hospital staff mounted a search and she was later found dead in a nearby park.

A report published last month said action was needed to prevent future deaths, warning that the new model could “allow each agency to regard such a situation as the other’s responsibility, whilst nobody is on the ground attempting to retrieve a seriously ill patient”.

Coroner Mary Hassell said she was concerned that police had not responded, adding: “If partner agency working is to be effective in caring for this extremely vulnerable cohort of patients, there needs to be crystal clear understanding by all those involved of how to tackle these difficult situations and exactly who is meant to be doing what.”

The Mind charity said the government’s focus on saved police time was “deeply worrying”, and that people could be “abandoned without support” if changes are not carefully implemented.

“This announcement goes nowhere near offering enough guarantees that these changes will be introduced safely – there is no new funding attached and no explanation of how agencies will be held accountable,” said chief executive Dr Sarah Hughes.

“It would be dangerous for forces to step back while local communities and health systems work out how to respond.”

The Royal College of Psychiatrists said mental health services were “chronically underfunded” and that a uniltateral police withdrawal would “pose a real danger to patients”.

President Dr Lade Smith CBE added: “The fact is that there are certain legal powers only held by the police, and so mental health is always going to be police business and they will always be needed in some form.

“While the reasoning and ambitions behind the ‘Right Care, Right Person’ approach are largely sound, it is important to remember that it has been trialled in just one area of the UK … an evaluation of clinical outcomes, or benefits and harms to the local population has yet to be conducted.”

Officials said there had not yet been any adverse findings over deaths in forces where the model is already used, and that national proposals had been discussed with the Chief Coroner of England and Wales.

Mark Winstanley, chief executive of the Rethink Mental Illness charity, said the agreement was “right in principle” but that it was “unclear how its ambitions will be fulfilled”.

“We must not have a situation where the police are stepping back unilaterally without any health and care provision to take its place,” he added.

“We have to recognise that there are no simple, quick or low-cost solutions on the table to absorb the one million hours of police time set to be ‘freed up’.”

The National Police Chiefs’ Council said officers would still respond to incidents where there is a significant safety risk or crime is being committed, but that people were currently being “criminalised” when they needed a health response.

Deputy Chief Constable Rachel Bacon, the national lead for mental health, said: “Police will always attend incidents where there is a threat to life. This is not about us stepping away from mental health incidents, it is about ensuring the most vulnerable people receive the appropriate care which we are not always best placed to provide.”

Emergency call handlers will be in charge of a new triage process, but officials said risk assessments could be updated in response to events on the ground. Each regional force must individually agree a “bespoke implementation plan” with local agencies before introducing the model.

It is based on processes developed by Humberside Police in 2019, and similar initiatives have been implemented in Hampshire, Lancashire, South Yorkshire and North Yorkshire.

The Metropolitan Police has been forced to row back on an announcement it would withdraw responses to mental health-related calls by 31 August, following a warning from NHS leaders.

A letter seen by The Independent said the change would be implemented over two to three years instead, and primarily focus on specific areas including welfare checks, people absconding from healthcare facilities, patient transport and handovers of people sectioned under the Mental Health Act.

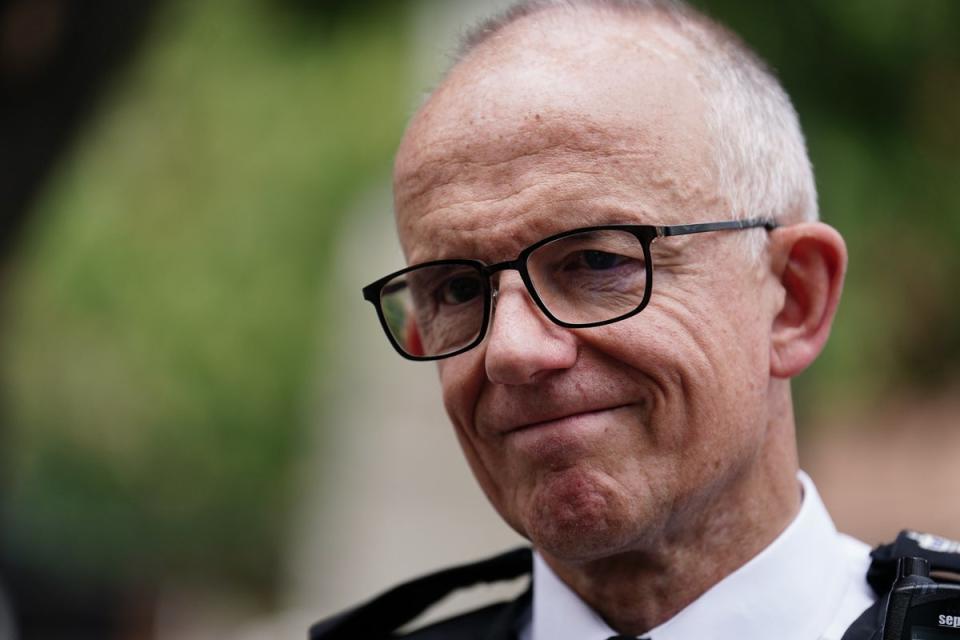

Caroline Clarke, the NHS director for London, said Sir Mark Rowley’s announcement had caused “anxiety and uncertainty across the health and care system”, and that NHS community health teams was already dealing with rocketing crisis referrals.

But Mr Philp, the policing minister, said the government had “listened to the concerns raised by police leaders about the pressures that mental health issues are placing on policing, which takes officers’ time away from preventing and investigating crime”.

Health minister Maria Caulfield, said the agreement would “ensure the most appropriate health care is provided as quickly as possible”.

“We’re going further and faster to transform our mental health services, with £2.3bn extra funding a year by March 2024 so two million more people can get the support they need – and £150m to build new and improved mental health urgent and emergency care services,” she added.

Work is also underway to provide 24/7 mental health crisis phone lines, and increase the number of specialist staff nationally.