The Gap in Life Expectancy Between Genders Is Getting Bigger. So, What’s Killing Men?

Something’s not right. In 2003, Adam Alderson, a 24-year-old tree surgeon based in the small North Yorkshire village of Preston-under-Scar, noticed a dull discomfort in his bowels. ‘It wasn’t really painful at first, but there was a problem there,’ he says. ‘It would come in bouts, so I’d be alright most of the time. Then it started happening more frequently,’ he says. After weeks of brushing it off as a mild inconvenience, Adam went to see his GP, who told him that he probably had irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). He was prescribed a fibre supplement and sent on his way. The discomfort persisted, but what could he do? One in three Brits experience IBS symptoms – hardly an extraordinary complaint – and Adam wasn’t one to make a fuss. He was fit, young and active. There werebigger things to worry about than an occasional bout of diarrhoea.

By the time he was diagnosed with an aggressive form of cancer called pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) 10 years later, Adam knew that he urgently needed help. ‘As men, we’re conditioned not to really talk about our health too much, especially if it’s something that’s worrying us,’ he says. ‘We tend to bury our heads in the sand and hope that our illnesses will just go away. We’ll search for every other thing possible for them to be, other than what they actually could be.’

But now, Adam was seeing blood in his stool. His bowel pain had escalated slowly over a period of years. Twice a day after meals, he had diligently taken sachets of the laxative Fybogel that he had been prescribed; he had also tried taking the IBS medication Buscopan. His condition, however, had continued to worsen. ‘I was going to the toilet 20 times a day and had a lot of pain,’ he says. ‘Things were getting really bad.’

Adam was 34. He was losing strength and had a distended abdomen. For a time, he had persuaded himself that his ever-swelling belly was simply a sign of ‘good living’ – he had recently relocated with his partner, Laura, to Adelaide, Australia, and had been making the most of the coastal lifestyle, drinking cold beers in the sun and cooking up barbecues on the beach. ‘Our life was good – really good,’ he says. But with his cancer diagnosis on Christmas Eve 2013, it all came to an abrupt end.

Mind The Gap

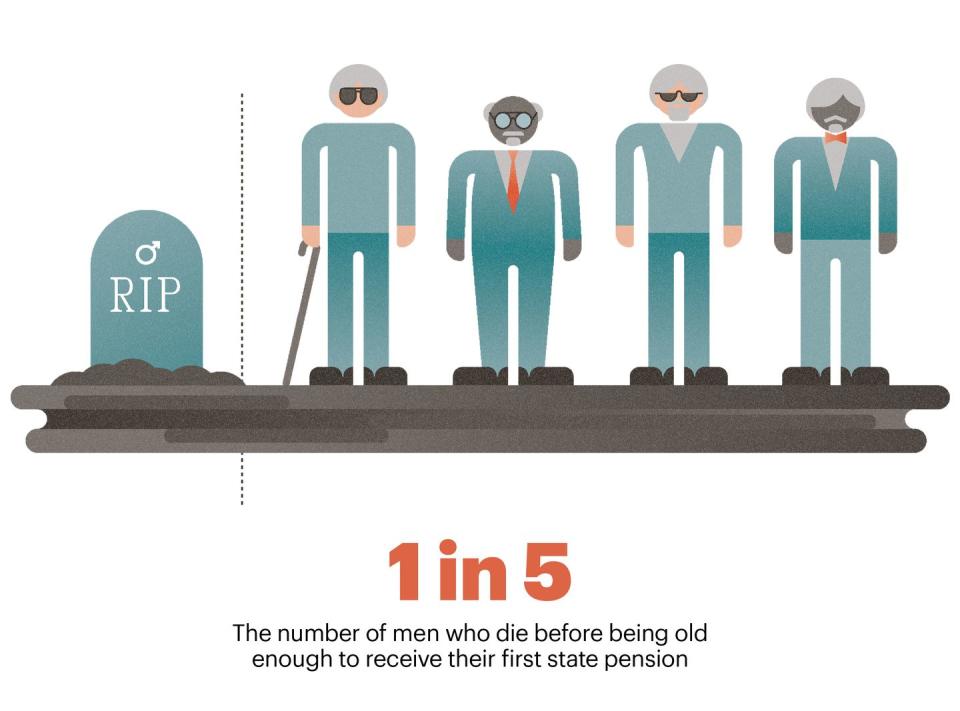

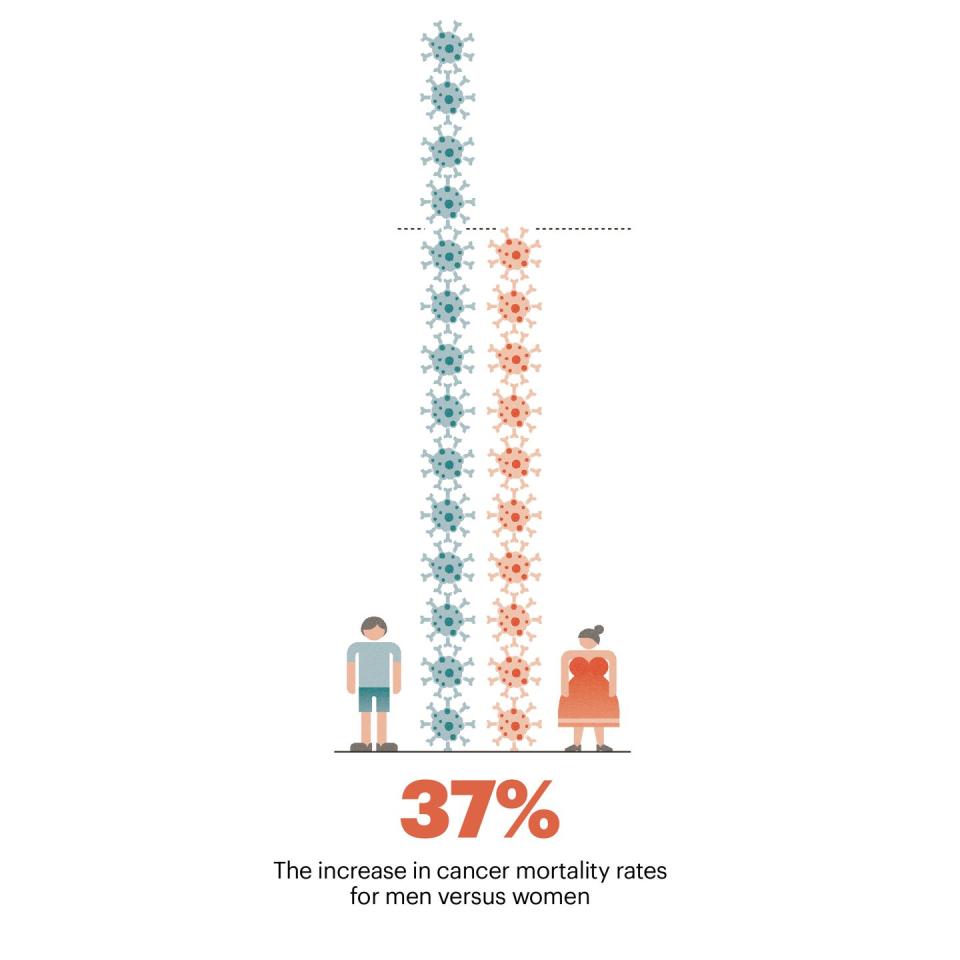

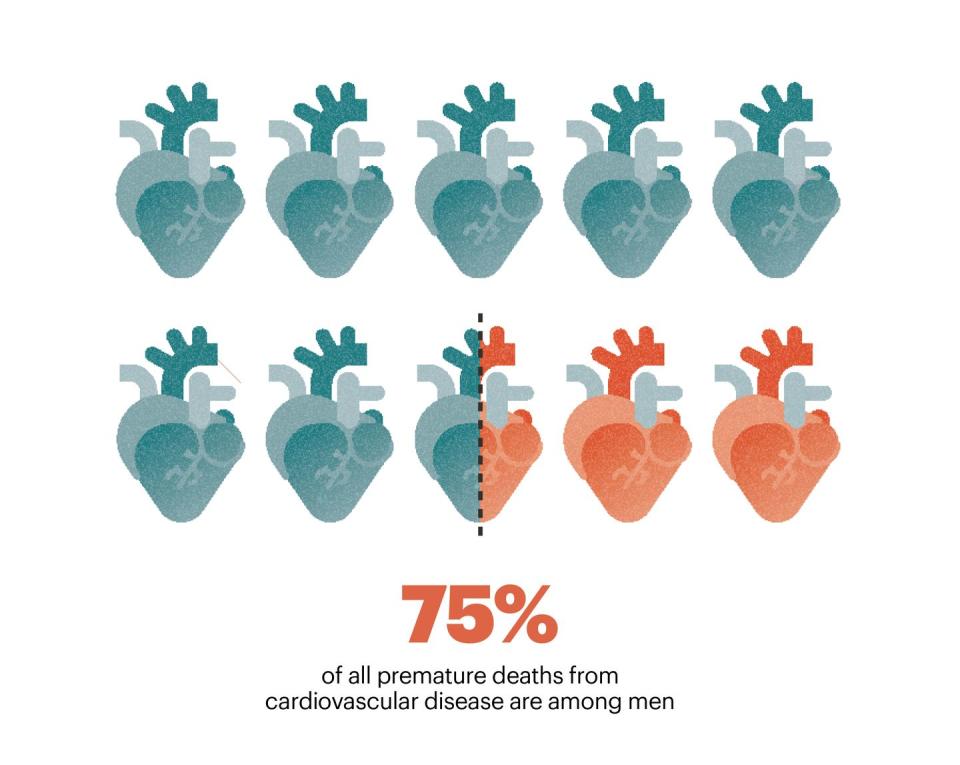

In the UK, one in five men dies before he is old enough to receive his first state pension payment. Men have a greater risk of death than women at every age between birth and 75, from a wide range of causes, including obesity, workplace accidents and heart attacks. We have a 37% higher mortality rate from cancer than women; 75% of all premature deaths from cardiovascular disease are among men. Four in five British people who take their own lives are men. (For men under the age of 35, suicide is the single biggest cause of death.) At the height of the Covid pandemic, men were 68% more likely to die after contracting the illness than women. According to the Office for National Statistics, male life expectancy in this country is a little under 79 years. For British women, it’s just under 83. In other words, women outlive men by an average of four years.

What could you accomplish in that time? You could master an instrument, progress from novice to black belt in judo, complete an undergraduate degree or even circumnavigate the world on a cruise ship 15 times. You could fall in love, raise a baby into a small child and jog about 1,000km over 200-odd weekly parkruns. Almost four years of walking and talking, doing chores, doing your groceries, watching movies, staring out of the window, simply spending time with your loved ones. More than 1,420 days of precious, ordinary life. Yet we lose that time. Why?

Attempting to find out, last July, the UK government’s Health and Social Care Committee launched an inquiry on men’s physical and mental wellbeing. MPs were tasked with establishing why we had higher levels of disease than women, why we were more reluctant to seek medical help and what issues lay behind the gender gap in life expectancy. ‘Some aspects of men’s health are just too rarely talked about,’ said Steve Brine, the committee’s chair and the Conservative MP for Winchester, as he announced the call for submissions. This was a rare, formal opportunity to have that conversation. Doctors, politicians, researchers, campaigners and representatives of charities such as Movember and Prostate Cancer UK all came forwards to share their perspectives.

What the committee has revealed so far – its evidence sessions are ongoing – is predictably complicated. The drivers of premature deaths among men include biological factors, low male health literacy and the chronic underfunding of our medical services – the legacy of years of austerity policies. Anthony Davis of the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy called for more state initiatives specifically targeted at men to counter the ‘stigma around seeking help due to traditional masculine norms’. Justin Varney, Birmingham City Council’s director of public health, argued for an increase in ‘access to occupational health in employment settings’, which would help to address the problem of men being forced to choose between work obligations and seeing a doctor.

A major theme that runs through many of the testimonies was men’s lack of engagement with the medical services in comparison with women. The stigma around seeking help that Davis cited is a global phenomenon: the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality has warned of how American men skip routine check-ups far more often than women in the country. At one of the Health and Social Care Committee evidence sessions, held in January, Movember’s Amy O’Connor spoke of British men’s ‘maladaptive coping mechanisms’ that were fuelled by the perception that it was unacceptable to ‘be vulnerable, look after themselves and not be stoic’. Overcoming this attitude – a potentially lethal form of toxic masculinity – is an urgent matter. ‘Seeking advice regarding health concerns needs to be more normalised among men,’ Anthony Cunliffe, the national lead medical adviser for Macmillan Cancer Support, tells me. He stresses the importance of ‘encouraging men to see it as okay to discuss their health with their friends and colleagues’.

Related to this is what Martin Tod, the chief executive of the Men’s Health Forum, described to the committee as our ‘weaker relationship with the health system’. Middle-aged men are the lowest-performing cohort when it comes to engaging with doctors. Women, on the other hand, tend to access primary care relatively frequently because they are more likely to be involved in reproductive health, while also being rightly encouraged to come in for breast and cervical cancer screenings. Direct outreach to men of a similar kind is limited.

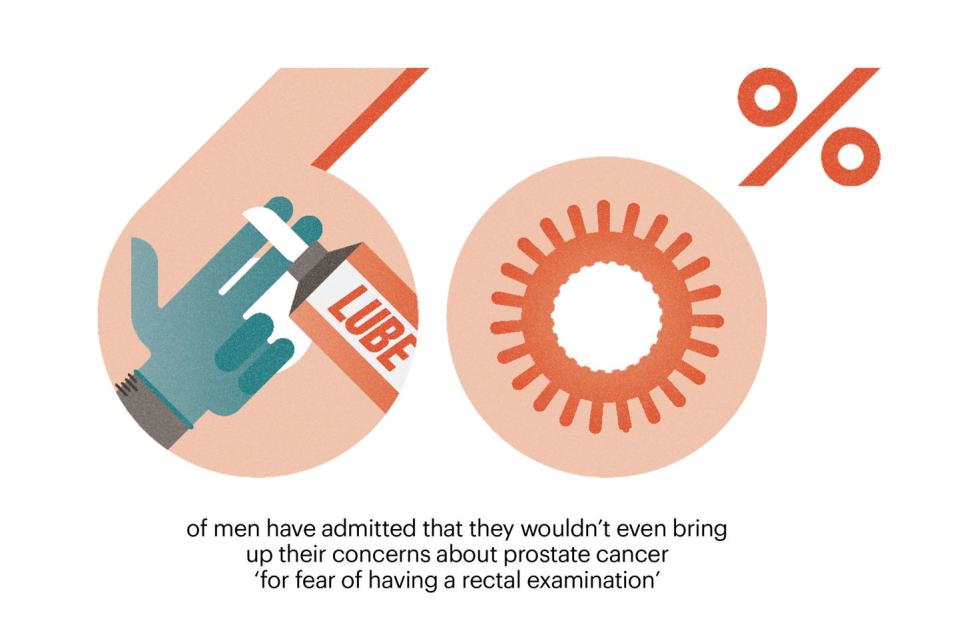

And the resulting remoteness of medical care for men can contribute to unnecessary embarrassment about certain routine procedures. Smear tests, which involve the insertion of a tube-shaped tool called a speculum into a woman’s vagina, are largely considered an ordinary part of female healthcare; according to the NHS, almost 70% of women aged between 25 and 64 attend their cervical screening within the recommended time frame. As many as 60% of men, however, have admitted that they wouldn’t even bring up their concerns about prostate cancer ‘for fear of having a rectal examination’, as Chiara de Biase, the director of support and influencing at Prostate Cancer UK, told the committee. Such hesitance can needlessly cost lives. The five-year relative survival rate for men diagnosed with local or regional prostate cancer is almost 100% – but, in 2018, it overtook breast cancer to become the third most common cause of cancer-related deaths in the UK.

Dismantling such psychological barriers, which often involve a tangle of anxieties relating to cultural norms or sexuality, is no small task. In the UK, for example, prostate cancer affects more than 50,000 men a year, of whom about 12,000 die from the disease. Though black Britons have a threefold relative risk compared with their white peers, they are considerably less likely to have been tested for it. De Biase of Prostate Cancer UK linked this to a mistrust of the health services, as well as ‘barriers to access, cultural references and the language that we use and ideas around masculinity and thoughts on faith’.

Many in the sector are working to address this. Tod told the committee that the Men’s Health Forum had trialled a scheme with the Race Equality Foundation in which black barbers were supplied with information that would help them have conversations with members of their communities about their health issues. Such efforts to ‘go to where men are’, Movember’s O’Connor said, can be a practical means of strengthening men’s relationship with the health services – a way to speak our language in familiar settings where we are more likely to be comfortable. The charity has similarly partnered with an organisation called Rugby League Cares to involve sports coaches in ‘providing mental and physical health training for our young men’, while groups such as Andy’s Man Club have created spaces in which men can feel free to discuss their concerns without any judgment or pressure.

For such strategies to succeed at a national scale, however, a reliance on the voluntary sector might not be enough. Mark Brooks, the men’s health consultant and founding trustee of the Men and Boys Coalition, told the committee that there’s a desperate need for a ‘whole-system approach’, in which issues specifically affecting the UK’s male population would be tackled as a unified subject. ‘Once you start treating men’s health as a thing, and something that we need to look at nationally and locally, you change the conversation and the narrative around men’s health,’ he said.

Paulette Hamilton, the Labour MP for Birmingham Erdington, agreed. ‘The reason why men are falling through the cracks is that [the current system] is not joined-up enough,’ she said. ‘Everyone believes that they don’t have ownership of men’s health.’ What that means is that the health services must adopt a more holistic strategy encompassing men’s race, class, social milieu, poverty levels and financial wellbeing, as well as factors relating to accessibility.

‘The key thing is that, if we continue to go down the conditions-based approach to men’s health [in which individual illnesses are dealt with separately], we are not going to pick up issues that affect all the different conditions that men face,’ Brooks told the committee. Unless specific bodies are created – and properly empowered – to deal with these diverse problems in an integrated manner, he argued, ‘nothing will change’.

A shift of this nature would require concerted government action, as well as money to finance it. But does Westminster have sufficient political will to enact such changes? Since the Cameron years, our health services have been starved of cash. According to the British Medical Association, the decision by successive governments to deviate from historic funding growth rates resulted in a cumulative underspend of about £322bn in real terms between 2010 and 2022; though the NHS’s budget has increased almost every year, it has not made up for this shortfall or kept up with rising demand. Against the backdrop of cuts to front-line services, a crisis in the recruitment of medical staff and a vastly inadequate provision of social care and mental health services across the UK, it remains to be seen whether the boldest ideas aired before the Health and Social Care Committee will be adopted in the near future – or at all. So, beyond pressuring your local representatives to prioritise the delivery of the services that you most need, what can you do?

Explore Your Options

In early 2014, Adam Alderson woke up on a hospital bed to the sound of the Jeremy Vine show, coming from a radio somewhere in the room. Since his PMP diagnosis the previous December, he had left behind his job, his home and his friends in Australia and returned to the UK for treatment at The Christie NHS Foundation Trust in Manchester, which specialises in cancer care. He had been told that his emergency surgery – thought to be his last hope – would take roughly 13 hours. But he guessed from hearing Vine’s voice that he had been unconscious for three hours at the most. A doctor approached and explained the situation to him. ‘I’m really sorry, Adam,’ he said. ‘When we got inside, the cancer was much more widespread than we’d anticipated. It was everywhere.’ The procedure had been aborted. Adam was placed in palliative care and told that he had two years to live.

But he refused to accept that he would die – not so soon, and not like this. From a hospice in Teesside, he ‘started sort of googling around’ and learned everything that he could about his condition. He made contact with specialists at other hospitals and discovered an online support group for PMP patients and survivors. ‘These communities are really important,’ Adam tells me. ‘There’s no better person to speak to than someone who has been through it all before.’ Conversations with fellow cancer patients demystified his illness and gave him new strength.

It was through these channels that Adam learned of a radical procedure that had previously been attempted on Steve Prescott, a rugby league player who had also been diagnosed with PMP. Prescott had volunteered himself for what the patient community refers to as MOAS, or the mother of all surgeries, in which multiple organs need to be transplanted at once. Though his operation was initially deemed successful, he died from complications resulting from it three weeks later.

Adam knew that it was a high-risk procedure, but he put himself forward for the same kind of surgery. When his doctors in Manchester tried to dissuade him, he independently sought out Brendan Moran, a Hampshire-based PMP specialist, for a second opinion. To his relief, Moran agreed that it could work and a plan of action was put in place.

One night in July 2015, Adam was awoken by a phone call from Moran. Suitable donor organs had been found. It was time. After hurrying to the hospital, he said goodbye to his partner, Laura, in a small waiting room. ‘I didn’t know whether I’d see her again,’ he says. Then he was taken into the operating theatre. Over the next 18 hours, 30 doctors and nurses worked on his body. They removed a 10kg tumour, his stomach, his bowels, his gall bladder, his pancreas, his appendix, his spleen, his abdominal wall and much of his liver, replacing what was necessary with the donor organs. Then it was over. Against the odds, the operation was a success.

Now Or Never

What happened to Adam could happen to you. ‘We all think that we’re here forever and nothing’s going to go wrong – until it does,’ he says. ‘We, as men, need to stop being apathetic about their health. It’s an emotionally painful situation to go to the doctors and say, for example, “I’ve got something wrong with my testicle.” We might not like the thought of a doctor putting a finger up our arse or handling our balls – I get why we’d want to avoid that because it’s an embarrassing situation. But as someone who lost every bit of dignity when I went through my journey, trust me: it’s easier to have things looked at before they get to the stage where they got for me. You don’t want to end up having to go through something as horrific as that.’

These days, Adam is in the gym three times a week. He is currently training to take part in the Ride Of Their Lives, a charity horse-riding event for Macmillan Cancer Support. ‘I keep myself mega fit,’ he says. ‘I’m not saying that we all have to be elite athletes, but if we don’t look after our bodies, our bodies won’t look after us.’ No longer a tree surgeon, he now works as a patient consultant for a research organisation called the Oxford Transplant Foundation, while also sharing his story at events as a speaker. Finally engaging fully with his health saved his life but, for him, it was almost too late. Now he raises awareness about cancer and assists doctors in discovering new ways to help others.

Echoing the experts at the Health and Social Care Committee inquiry, Kamila Hawthorne, the chair of the Royal College of General Practitioners, tells me that there is no single cause behind the disparity in life expectancy between men and women. It might be the result of anything from ‘differences in biology’ to ‘income, education, housing and diet’ – or a combination of all of these factors. (Men, for example, are far more likely than women to smoke and drink in excess.) Faced with this uncertainty, we should ‘take positive action to live healthily’, she says. But knowing what that truly means involves a conscious engagement with our health – and being man enough to accept that it’ll one day fail. We’re not impervious or invulnerable. And while the government ponders structural solutions to the problem, we need to take the initiative, find the strength to listen and talk about our vulnerabilities. ‘We only have one body, one chance at this,’ says Adam. ‘And it can suddenly be too late.’

You Might Also Like