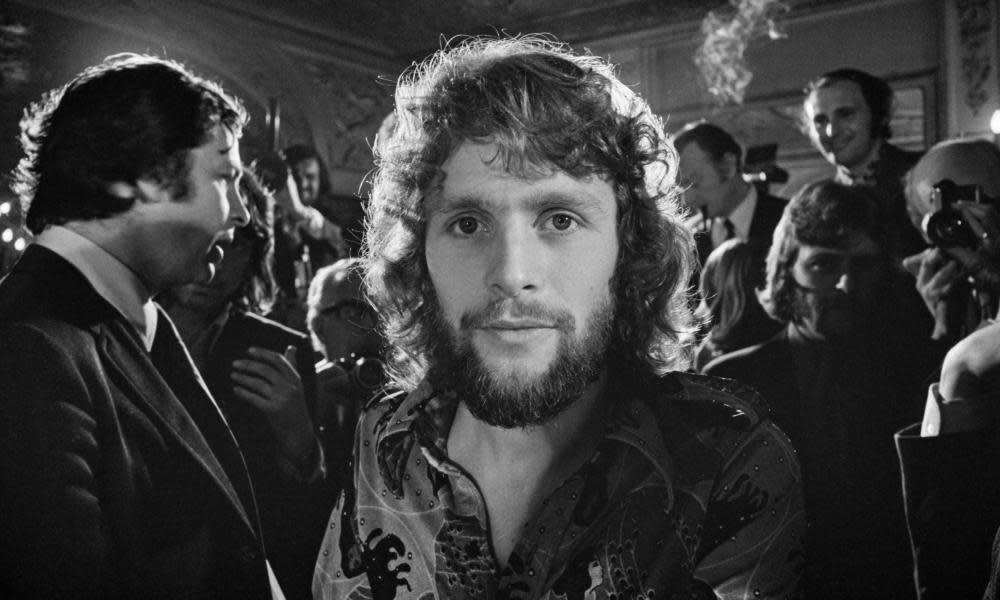

‘If you have dreams, follow them!’ Paul Nicholas on Bowie, the Bee Gees, playing Jesus – and ruffling the king’s hair

When he was starting out as a young man in bands in the early 60s, Paul Nicholas could only have dreamed that he would still be working more than 60 years on. He is now nearing the end of a seven-month theatre tour. It must be tiring by this stage, I suggest. But no, he says. “It’s really the one thing that I enjoy doing more than anything. Performing on stage is kind of a release for me.” He smiles. “It sounds a bit heavy, doesn’t it?”

Nicholas is about to release the audio version of the memoir he wrote during lockdown, which covers his career from failed rock singer to successful pop star, from being the first actor to play the lead in Jesus Christ Superstar to being part of the original cast of Cats, appearing in numerous films including the cult hit Tommy and the 80s BBC sitcom Just Good Friends. In recent years, Nicholas has appeared in EastEnders and the reality show version of The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel, among others.

Over a video call from a low-cost hotel room, he seems fun and lacking in self-importance, as does his book. It made me laugh, often intentionally – going to dinner in Paris with Serge Gainsbourg and Jane Birkin in the 60s, 24-year-old Nicholas is taken to a restaurant where they serve only flowers and he asks for chips with them. But sometimes it’s just his turn of phrase, almost Partridgean at times. On being asked to invest in an Andrew Lloyd Webber musical: “Now, I had saved a bit, but not enough that I wanted to blow it on a show about cats.” His inclusion of a Private Eye report on his father, the flamboyant showbiz lawyer Oscar Beuselinck, made me laugh out loud: “Never marry,” warned Oscar, who had divorced three times. “I reckon my cock has cost me £100,000 per inch.”

With a father like that, says Nicholas, “you could either go the other way and become a priest or you could find yourself expressing yourself with a similar kind of humour at times, which of course is deeply inappropriate. I have to be careful, but I still find myself making mistakes, I’m afraid.” Later, he asks me if I “detect an old dinosaur”. “Having grown up in the 60s, and having that freedom to say what you want, now we’ve regressed a little bit. Overall, it’s good that people are more careful about how they speak about others, but there is a willingness among some people to be offended.”

His book is so un-PC that it’s almost quaint. On at least two occasions, Nicholas describes female co-stars, of similar vintage to him (he is 78), as “still an attractive lady”, as if it’s surprising at their advanced age. His wife, Linzi, to whom he has been married for more than 50 years, is always telling him off, he says. Recounting a sex scene in one film, he writes that he gives his co-star – who happens to be the wife of the director – a “tongue sandwich”. “Did I say that? Please forgive me,” he says with a laugh, but also looking aghast. “I think I was overdramatising the tongue. It sounds very energetic, and I wouldn’t have been that energetic.”

During the second world war, Nicholas’s father apparently worked for MI6 “because he could speak Flemish, so he was quite useful”. His mother, Peggy, worked at Bletchley Park, and he likes to say she cracked the Enigma code “but she wasn’t a codebreaker, though she wasn’t bad at crosswords”. Until Oscar, who had started at a law firm as a tea boy at 14, advanced through the ranks and then specialised in showbiz – he brokered contracts for the Beatles and Sean Connery, among others – the family wasn’t well off. They moved in with Nicholas’s grandmother on a council estate in north London until Nicholas was seven. Then Oscar bought a house and, later, once his parents had separated, Nicholas and his mother lived in a flat.

It was his mother who took him to the cinema and introduced him to performing. England in the late 40s and 50s, he says, “seemed to be a very grey place, but colour in my life came through film – and I particularly liked musical films. I used to go home and imitate Gene Kelly, tap dance on the lino.”

Nicholas was in bands while still at school, including his own, Paul Dean and the Dreamers, but “we weren’t really going anywhere”. When his guitarist joined Screaming Lord Sutch’s band, the Savages, Nicholas went to see them. “I was amazed at [Sutch], who had really long hair down to his shoulders in 1961, which no one had. I loved his act. He lit a fire on stage; it was a very outrageous act.” Nicholas joined the band. “What was great about that for me was that it wasn’t just standing there singing; there was a sense of theatre about it. Much more fun.”

During Sutch’s song Jack the Ripper, Nicholas dressed up as one of the serial killer’s victims and would be murdered on stage every night by Sutch, who would hold aloft a pair of bloodied rubber lungs; at one point, he started using animal hearts procured from the butcher. When Sutch, the founder of the Monster Raving Loony party, stood for parliament against Harold Wilson in 1966, Nicholas ran around in leopardskin, handing out leaflets.

Nicholas’s next band toured with the Who, then he tried to become a solo star and was taken on by a manager, Robert Stigwood, who would go on to manage Cream and the Bee Gees. The Who’s Pete Townshend wrote a song for him, as did the Bee Gees (who sang backing vocals on his single) and a young David Bowie. “He was very stylish, as you would imagine, even then,” says Nicholas. “He was quite serious, I thought, for a young man. He told me about learning to be a mime artist and did a bit of mime for me, you know, putting the hands on the windows.” The song Bowie wrote, Over the Wall We Go, inspired by a number of jailbreaks, was banned by the BBC, says Nicholas. “It was too outrageous to become a hit. I had really quite a long go at becoming a pop star without any success.”

He took an office job at a music publisher – by then he was married with two children and it was stable work – but when auditions came up for a new musical, Hair, inspired by the hippy counterculture, he went. He got the lead role. The musical opened in 1968, the day after a 200-year-old legal act censoring plays was abolished. “There was a freedom,” says Nicholas. “It was the beginning of women becoming freer. It was kind of throwing off the shackles of the 50s. All that music was happening here. It was a big awakening for London and the UK, and Hair was part of that. It was exciting.” Sometimes cast members would smoke weed on stage. “You’d think: ‘We’re supposed to be playing hippies, we aren’t really hippies.’”

Next, Nicholas auditioned for Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice’s musical Jesus Christ Superstar. Lloyd Webber, he remembers, was “very foppish. He was in the style of the moment, but quite flamboyant, quite gentlemanly, in some ways rather 18th-century.” The musical was exciting, he says, “because it was considered to be a rather taboo subject, calling Jesus Christ a ‘superstar’. A superstar in those days was pretty out-there.” There were protests outside; it was Nicholas’s “first experience of really being in the limelight”.

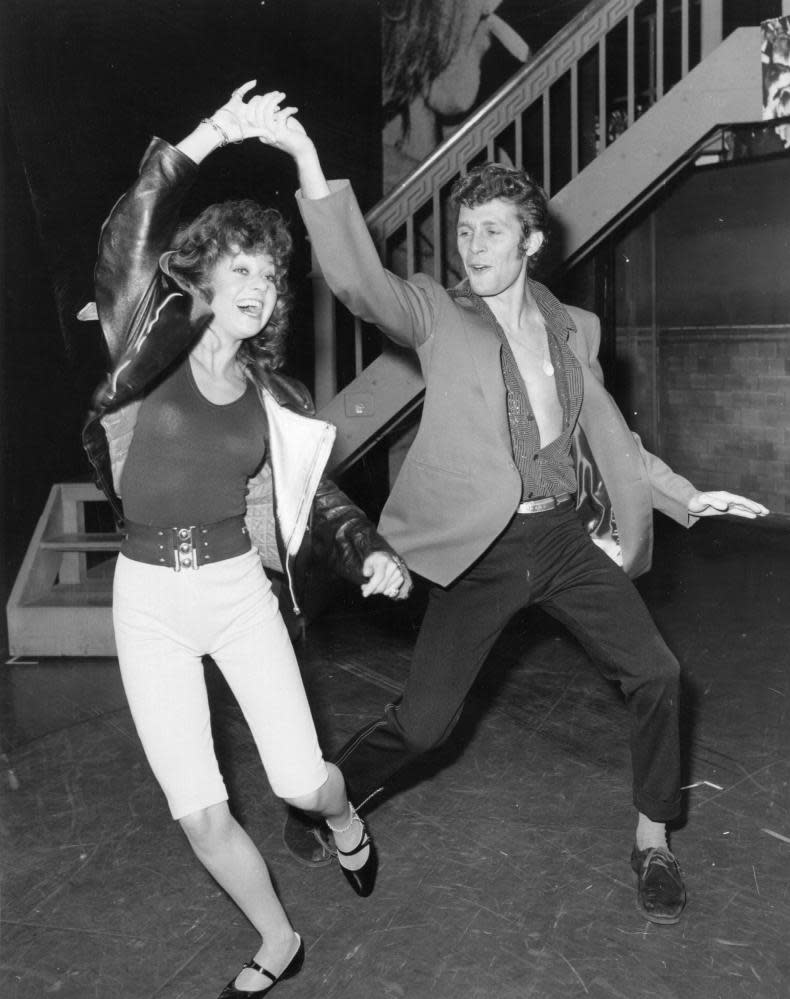

After Grease with Elaine Paige, “I thought: ‘You haven’t done any real straight acting.’” He was invited to do Much Ado About Nothing at the Young Vic. “I bought the play, had a look at it and didn’t understand it. If you don’t know Shakespeare, it takes some interpretation.” There was a snobbishness that musical theatre actors weren’t considered “proper” actors. “Not by them all, but by one particular actor who was in it. We had a few cross words in the wings one night and a slight dust-up, not major, and then we had to go on and be friends in the play.” An opportunity to play Hamlet in a musical version in New York fell through because Nicholas couldn’t get a work visa. “I wasn’t considered a name worthy enough in America to usurp an American actor,” he says. And so Nicholas decided he needed to become famous. The best way, he thought, was to become a pop star after all.

Incredibly, he managed it – he had three UK hits, including two Top 10s, and got on to Top of the Pops. I don’t even know how to describe one of his hits, Reggae Like It Used to Be. One YouTube comment under his flare-wearing performance perhaps sums it up: “This might just be the whitest thing anyone’s ever done.” Nicholas smiles when I say this might get him cancelled now. It wasn’t a reggae song, he says in (feeble) defence, “it was a song about reggae”.

He was a bubblegum popstar and teen heart-throb, even though he was in his early 30s. “I even got an afternoon pop TV show, which I hosted, called Paul, so I was really out there as a young pop singer, even though I was rather an old pop singer.” He laughs. “But I was playing a character.” He’d tried to be like a pop star, he says – he would go to fashionable clubs to drink vodka. “But I was crap at it. I used to go home and throw up.” By then, he had split up from his first wife and was in a relationship with Linzi, but he had a lot of attention from female fans. “As a result, my darling lady decided that things shouldn’t be continuing as they were and decided to leave, which she did. Which was difficult.”

Things got even worse – his first wife was killed in a car crash, and he became sole parent to their two children (he also had two from before his first marriage). “Linzi came back and helped me through that terrible time, and we’ve been together ever since. It was a horrible, horrible time for everybody and without her I don’t know what I’d have done. She took on two children and our family.” Later, they got married and had two more children. “It’s been like that ever since, except they’ve all gone – now the grandchildren are coming.” He has six children, 13 or 14 grandchildren – “I haven’t added them up lately” – and three great-grandchildren.

How much of his long marriage was down to a reaction against his father’s philandering? “Well, when I was 16, if you were in a band, it was one-night stands, because you were never home long enough to have a girlfriend.” Linzi, he says, “was the stable thing that I needed, and she has given me that over the years. I don’t quite know what I’ve given her.” His father, he thinks, was a shy man whose sexual bragging may not have been entirely true. “I think most of it was bullshit. I think it was reserved for other men, rather than women. He always seemed to me very courteous around ladies. He was in a profession that was quite strait-laced, but he was dealing with showbusiness people, who were the opposite, and I think that was part of his charm for them.”

In 1980, Nicholas was cast in Cats, which opened the year after. “I went over to [Lloyd Webber’s] place, and he played me these songs and I said: ‘Oh yeah, nice tunes.’ At Sydmonton Court, his home, he does this kind of festival every year where he tries things out, and so we performed Cats for 200 people in a church in his back garden. He seemed very pleased with it and the audience seemed to take to it.” He regrets not investing money in the production when he was asked. “It became probably the biggest hit that Andrew has ever had.” Nicholas, who played the rebel Rum Tum Tugger, was not as good a dancer as the others, and would run around the audience during the main dance piece. In his book, he recalls ruffling the hair around the bald spot of Prince Charles, sitting in the audience. “He seemed quite amused by it.”

The BBC sitcom Just Good Friends, written by the Only Fools and Horses creator John Sullivan and centred on his on-off relationship with his posher ex-lover (played by Jan Francis), cemented Nicholas’s mainstream fame in the mid-80s. It wasn’t that he wanted fame for fame’s sake, he says: “You never really have got control in this business, because you’re always reliant on someone calling you, but you stand more chance of [getting] work if you have a name.”

It was one reason he successfully went into producing, with an actor friend, David Ian. They put on Jesus Christ Superstar. “I said: I’ll play Jesus. That was good of me, wasn’t it?” His other successful shows include Grease and Saturday Night Fever in the West End. He is still looking for opportunities – he writes songs and made an album recently, and has written two sitcoms, which he is hoping to develop.

“You have to be a realist. I can’t play young romantic leads and do those things, but there are parts out there for older people. It’s such a terrible cliche, but if you do have dreams, follow them, because you’re only here once. Give it a go, and if you muck up, too bad, but you’ve had a go.” What has he learned about showbusiness in all these years? He thinks for a moment, looking slightly as if he can’t believe his luck. “I think the one abiding passion is to keep going.”