How Chamonix became the most famous ski resort in the world

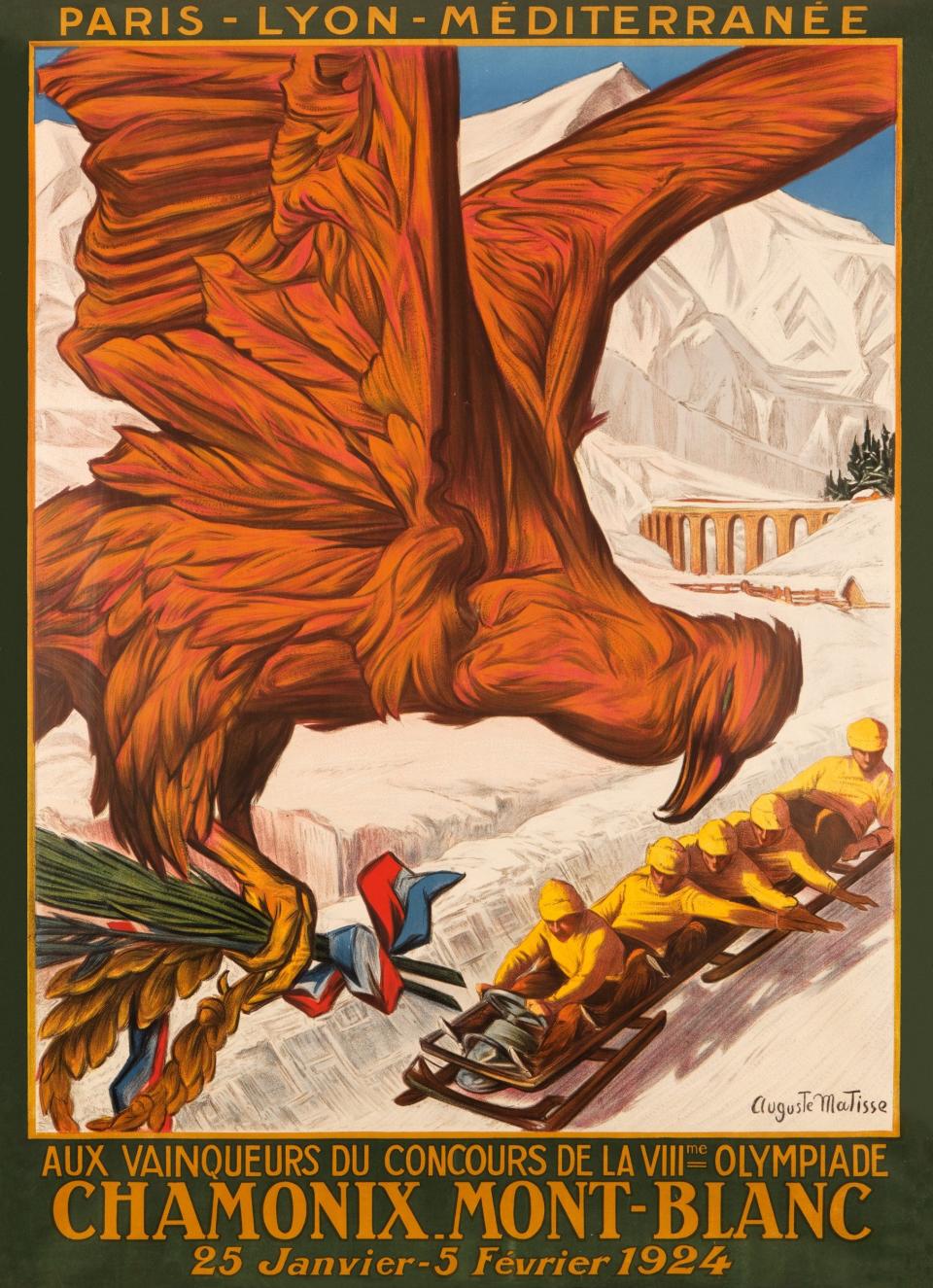

This winter Chamonix, the world’s most iconic mountain town, celebrates the 100th anniversary of the Winter Olympics, first held here in the shadow of Mont Blanc in 1924.

Prior to the historic event, the town was the world centre of alpinism – the lure of climbing some of the highest, hardest and most spectacular peaks in Europe had been attracting mountaineers for almost two hundred years, with the English aristocracy and members of the Alpine Club foremost amongst their number. Chamonix was also a popular venue for members of the Ski Club of Great Britain, led by Sir Henry Lunn, the founder of travel company Lunn Poly.

As snow and ice sports became more popular in the late 19th century, the International Olympic Committee was persuaded to create a winter version of the Olympics and Chamonix was selected as the first venue for the 11-day event.

It featured cross-country skiing, figure and speed skating, ice hockey, Nordic combined (ski jumping and cross-country skiing), ski jumping, bobsleigh, curling and military patrol, a forerunner of the modern biathlon – perhaps surprisingly there were no downhill skiing competitions, these not being introduced until 1936.

Hosting the event required the not-inconsiderable expense of building a ski jump, a 36,000-square-metre ice rink and a bobsleigh track – the Mont aux Bossons ski jump is still used occasionally today, but the ice rink and bobsleigh track are long gone.

Britain came sixth in the medals table, with the Scandinavian countries then, as now, dominating; France was ninth. And the weather was just as unpredictable as today – shortly before the Games were due to open, over 1.5 metres of snow fell in a single day, followed by a thaw that led to an avalanche, which blocked the local railway line and turned the Olympic ice rink into a lake. Fortunately, cold temperatures returned in time for the opening ceremony, which saw 300 athletes from 16 countries taking part, watched by 10,000 spectators.

The first Winter Olympics provided Chamonix with a perfect opportunity to market itself as a year-round destination – up until now tourists had largely visited only in summer, but over the coming decades the town and surrounding mountains were to become one of the world’s major winter sports destinations.

Within the Chamonix valley the Brévent cable car was built between 1928-30, followed by a succession of ski lifts and, in 1955, the spectacular Aiguille du Midi Téléphérique, then the highest cable car in the world, rising to a breathtaking height of 3842m.

It provided mountaineers with quicker and easier access to the Mont Blanc massif, allowed skiers to descend the Vallée Blanche – a thrilling and spectacular 20 kilometre backcountry ski run down the Mer de Glace glacier – and gave day-trippers an opportunity to see Mont Blanc’s magnificent glaciated alpine landscape up close. Further up the valley, the Grands Montets ski area opened in 1963, from where some of the most challenging freeride skiing in the world is accessible.

Chamonix further established itself on the scene with an annual round of the FIS Alpine Ski World Cup, numerous editions of the Kandahar Alpine Skiing World Cup (the latest one is scheduled for Feb 3-4) and, more recently, rounds of the Freeride World Tour. The town’s influence on winter sports, freeriding in particular, is well summed up by American ski legend Glen Plake, for whom Chamonix is a European base: “Whether it’s the history of the alpinist culture, the extravagant geography or the access to it, Chamonix is a pilgrimage.”

This pilgrimage is undertaken by winter sports enthusiasts from all over the world looking to challenge themselves on the area’s ski slopes – along with hard-charging locals, resident Britons, Scandinavians, Americans and Aussies are in abundance, with a smattering of visitors from other countries.

To cater for them, Chamonix offers everything from Michelin-starred restaurants to curry houses and burger bars, five-star hotels to bunk houses, and hipster bars and brewpubs to several nightclubs and a casino. Access is easy thanks to a major road that tunnels beneath Mont Blanc to Italy and the aforementioned railway line providing links to Geneva, Paris and London.

But the “endless snows” of Mont Blanc are changing as rapidly as the town beneath them, as a visit to the Mer de Glace shows. Over the past 140 years, the glacier has retreated 2km in length and 220m in depth. In Edwardian times, visitors used to take the 5km Montenvers rack-and-pinion railway from Chamonix to access the glacier from the platform at the 1,913-metre high Refuge du Montenvers, but in recent years it’s been necessary to climb down 550 steps to reach it (you also have to climb up them after skiing the Vallée Blanche – quite a slog with your skis slung over your shoulder).

A new gondola will replace the steps later this month, which is perhaps emblematic of how Chamonix is adapting to climate change. But it also makes you wonder if it will still be possible for the town to host the Winter Olympics, or any winter sports event at all, in another hundred years’ time…

Essentials

The Ski Club of Great Britain offers a Chamonix Off Piste Adventure trip from £1,595, for intermediate skiers upwards, on dates throughout February and March. The price includes seven nights chalet accommodation, six nights chalet board, and five days with mountain guides. Excludes travel.

Visits to the Mer de Glace, via the Montenvers railway, cost from €38.50 per adult; €32.70 per child (aged five to 14 years).