Burberry’s chief creative officer: ‘How do you reinvent the trench coat every season?’

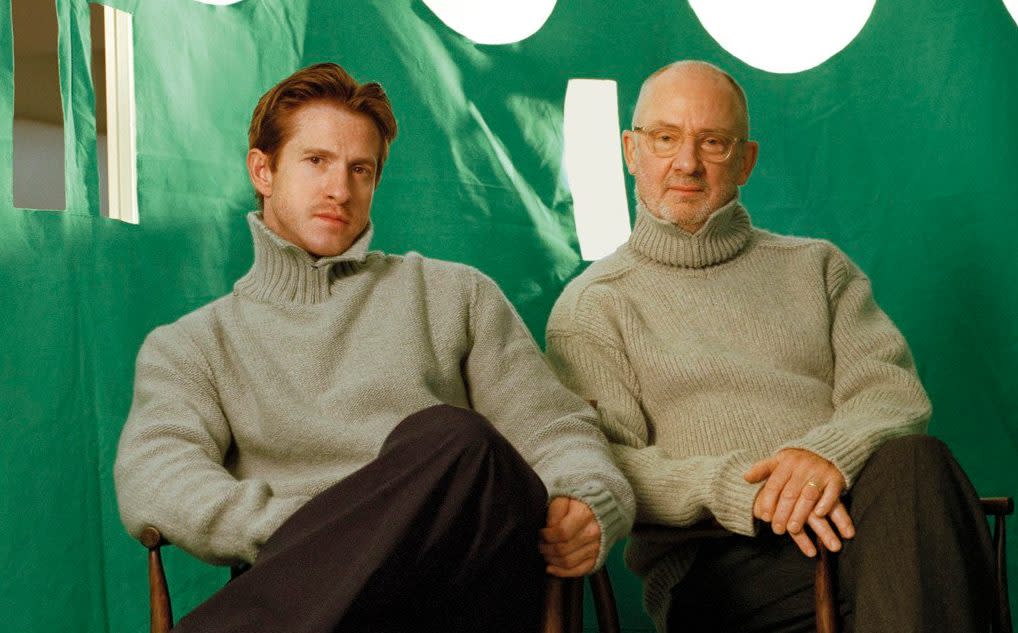

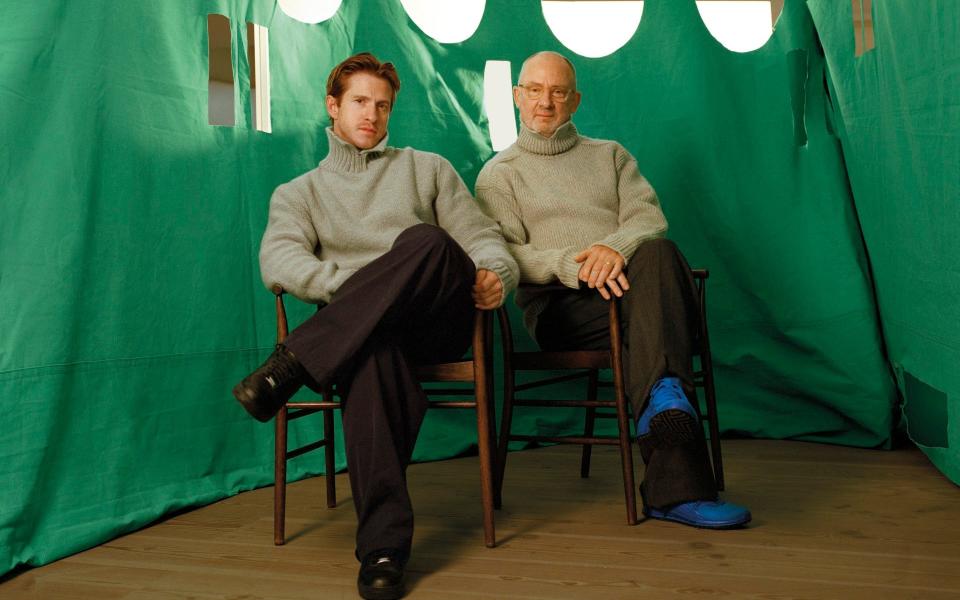

Inside a studio in Soho, two men are having a natter. Dressed in cashmere roll necks, and surrounded by tarpaulin sheets, they look like debonair polar explorers settling down inside a tent. Except, at regular intervals mysterious shapes have been cut, crudely but confidently, out of this heavy-duty fabric. And, from certain angles, these porthole-like circles and twinned rectangles call to mind the sockets and cavities of skulls.

What are these enigmatic banners, with their death’s head designs? For more than three decades, they were carefully stored by the bespectacled older man, 62-year-old British artist Gary Hume, who created them. Until earlier this year, when his companion, Daniel Lee, the 38-year-old chief creative officer at British fashion house Burberry, got in touch to ask if they still existed. Inspired by a photograph of them installed, in 1990, in a disused Docklands warehouse, Lee hoped they could be revived as a striking set for Burberry’s spring/summer 2025 runway show.

Similar in shade to the green of a surgical gown, Hume’s faded, forgotten tarps are linked to a series of life-sized paintings, first unveiled in 1988, depicting double-hinged swing doors inside east London’s dilapidated St Bartholomew’s Hospital. These macabre, anthropomorphic pictures made Hume’s name, and, like them, the tarps seem to emit an infirmary’s unsettling carbolic whiff.

Yet when I ask Lee if he minds their cranial associations (since evoking mortality isn’t an obvious strategy for a luxury brand), he laughs. ‘I didn’t really think about it, to be honest,’ he says in a quiet, high-pitched voice, his vowels redolent of Bradford, his birthplace, as if Arctic Monkeys frontman Alex Turner were speaking in an ethereal tone. ‘I like the immediacy of the cuts, and the shapes they make.’

In a trice I sense that, despite his soft-spoken demeanour, Lee isn’t to be trifled with – especially not during the run-up to London Fashion Week, days before one of Burberry’s biannual extravaganzas presenting his latest collection. Throughout its premises on Marshall Street (where Lee is temporarily based while Burberry’s Westminster headquarters undergoes renovation) there’s a sense of urgent endeavour, as otherworldly models arrive for fittings. The following day, when I meet both men again in Lee’s office – a bare, whitewashed space, in which the designer sits behind an empty desk, dressed in another heavyweight cashmere-blend jumper with epaulettes (now paired with grey Nike joggers) – the first thing he says is, ‘It’s a horrible week, I hate it,’ before backtracking: ‘I’m joking! I guess it’s nice to spend intense time with the team.’

Doesn’t this ‘peak stress moment’, as he calls it, provide a rush? ‘There’s a lot of adrenalin,’ he concedes, ‘and you’re consumed by all the work. You don’t have any clue what’s going on outside this bubble.’ Surely, though, he’s mindful of recent negative reports about Burberry, after a global slowdown in sales of luxury goods confounded the company’s ambitions to expand. This summer Burberry announced the departure of its chief executive, Jonathan Akeroyd, who in 2022 hired Lee to replace Riccardo Tisci, following his stint as creative director at Italian label Bottega Veneta (where he established his reputation as a fashion wunderkind specialising in accessories). How does Lee – who looks as though he could do with a decent night’s sleep – deal with these gloomy noises off? ‘You have to park it, not listen,’ he replies, rubbing his eyes. ‘Putting ideas out into the world can be very vulnerable.’

For his part, on the other side of Lee’s desk, sitting on a wooden chair draped with an olive-and-cream Burberry blanket, Hume seems blessedly stress free. A star of the irreverent, go-getting generation of Young British Artists (YBAs), he’s thoughtful and droll: when I ask if the paint splatters on his torn jeans are fresh, he deadpans, ‘Oh, no, they’re hand-embroidered.’ By his own admission, he’s no follower of fashion; for our interview, as well as those jeans, he’s dressed in an old brown Nike sweatshirt and a pair of electric-blue trainers by Danish shoe brand Ecco. ‘Don’t put that in,’ he jokes. ‘They’ll kill you if you mention another brand.’

According to the art dealer Lyndsey Ingram, whose exhibition of a career-spanning selection of Hume’s prints (many available, she says, ‘for less than the price of a Burberry handbag’) closed this week, ‘There’s nothing glib about Gary: he’s very intelligent, gentle and elegant – a bit subversive, too.’ She confirms that he’s never been spotted ‘in anything remotely fashionable’ – unlike his ‘super-chic’ wife, the artist and textile designer Georgie Hopton (whom Ingram represents). When I ask Hume how it felt to be swathed head-to-toe in Burberry’s tailored woollens for the shoot, he replies, ‘Hot.’

Still, his admiration for Lee is sincere. Between exhibitions, he explains, he typically has ‘two years, essentially by myself’. Recently he unveiled new work depicting flowers and swans, with a muted, autumnal palette, at Mayfair’s Sprüth Magers gallery (until 19 October); around the corner at Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert (until 26 October), he’s showing 12 seductive paintings from the 1990s that appear to be made of melting gelato. (In fact, they are done in high-gloss household paint, mostly Dulux.) But, he continues, Lee faces a non-stop ‘need to be creative’: ‘It’s just relentless – and that’s mind-boggling to me.’

Before this collaboration, the two men didn’t know each other: ‘This’, says Lee archly, ‘is a new relationship.’ Growing up in West Yorkshire, the eldest of three siblings, Lee wasn’t, as he puts it, ‘particularly surrounded by culture or art’; his father is a mechanic, his mother worked in an office, and, he tells me, ‘the only real artist I knew about in depth was David Hockney, mostly because he’s from Bradford as well.’ But he recalls that while he was studying at London’s Central Saint Martins, in the early 2000s, there was still excitement about ‘what had been happening in fashion and art and music in the 1990s’ – when Hume was flying high. In 1996 the artist was shortlisted for the Turner Prize; three years later, at the 48th Venice Biennale, he represented his country inside the British Pavilion (which Burberry now sponsors). There, he debuted his Water Paintings, which depict overlapping outlines of female nudes; one, with a lime-green background, is on display at Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert, where three paintings are for sale, each for about £200,000.

Since joining Burberry, Lee has taken inspiration from these Cool Britannia years: he recently unveiled a Classics campaign that featured Lennon Gallagher, the son of Oasis’s lead singer, Liam, and the actor and singer Patsy Kensit (whom in 1994 Hume depicted as a baby-pink apparition with khaki lips, against a peach ground). Although a bright orange print by the digital artist Christine Wilkinson hangs behind his desk in his office (‘I love the colour,’ he says), Lee tells me that he doesn’t really collect art: ‘I mean, I would like to; I have a few things, not so much.’

Still, he says, ‘Gary’s an artist I’ve admired for a very long time: I’ve always looked at his work for inspiration, [even] copying his use of colour, and combinations, at times.’ And Lee has never forgotten a ‘tiny picture’ he once came across in a book, documenting those alpine-green tarpaulins within the East Country Yard Show, an early group exhibition of artists later lumped together as the YBAs, co-organised by Sarah Lucas, Hume’s girlfriend for seven years. (Last year Burberry sponsored Lucas’s retrospective, Happy Gas, at Tate Britain.)

Confronted, he recalls, with a ‘ginormous’ space, Hume created 12 tarpaulins to fill six big recesses, divided by concrete pillars – hence the work’s title, Bays. He chose tarpaulin as a nod to the site’s history, since dockworkers routinely handled this water-resistant material. Burberry, Lee points out, is also ‘renowned for a kind of outdoor protective fabric’: the waterproof but breathable gabardine invented by the firm’s founder, Thomas Burberry, from which its trench coats are still cut. Sensing a ‘very strong connection, through the synergy of the fabrics’, Lee decided to ‘reach out to Gary, on a whim’.

In part to evoke the warehouse where Bays was first displayed, Burberry hired the National Theatre for its show: ‘We were searching for a beautiful concrete environment,’ explains Lee, and Denys Lasdun’s brutalist architecture, with its rough-cast concrete, fitted the bill. When I ask if the grime on the tarpaulins will be scrubbed off, Lee replies, sounding piqued, ‘We like the way they look.’ ‘It’s amazing how things come around,’ chimes in Hume, who reveals that, since the early 1990s, ‘I’ve been thinking about throwing them away, because they’re heavy, they take up room. Nobody wants them.’

In general, Lee relishes collaborations, because, he says, it ‘definitely inspires’ his own work. Typically, he tells me, ‘a new idea can be abstract – about a feeling, or a piece of fabric. Then, it’s about making something before destroying it and evolving it. That journey is where you find magic.’

Hume relates. Sometimes, to mix things up, he deliberately introduces ‘bad’ elements into a picture, ‘until it’s a total disaster, and I’m the worst artist in the world, and I might as well kill myself. Then, I panic, and try to make it better. And in that process, things turn up that I hadn’t imagined.’ He grins. ‘Most of the time, it’s very frustrating. You can get very upset and despondent and angry’ – although, he tells me, ‘It’s not histrionic, like in the movies.’ Is this what Lee’s like, when he’s creatively frustrated? ‘No,’ he says, giggling. ‘I think mine’s more of an internal panic.’

Hume is excited by their ‘creative common ground’, and observes that the art world, like the fashion industry, ‘is completely happy being a business’. But he’s also keen to point out an ‘absolute difference’ between their spheres: ‘The freedom I have is that I don’t have to do anything for anybody. And I don’t.’ ‘Absolutely,’ agrees Lee. ‘Ultimately, I have a boss, and that boss is the brand. So, I’m creating work that’s, yes, in my style, but also respectful of the heritage of the past… Like, every season: how do you reinvent the trench coat, the thing that’s so synonymous with Burberry?’

What about shoes and bags? Is Lee under pressure to create accessories and footwear as successful as, say, his Cassette and Pouch bags, or chunky rubber Puddle rain boots, which were huge hits during his time at Bottega Veneta? ‘I think so,’ he replies. ‘We’re striving to create products that can have the legitimacy of the trench coat.’ But, he adds, tentatively, ‘It’s a journey. I’m someone who hates everything they’ve done previously.’

He sighs. ‘I feel like I live more now in the corporate world. That’s the way my industry has evolved.’ Does he lament this change? Lee puffs out his cheeks. ‘I did enjoy the scrappiness when I started out. It was a little bit more insane. It was fun. Now, it’s definitely more serious.’ But, he says, ‘ultimately, it gives you access to a nice life.’

Hume’s success has afforded him a ‘nice life’, too. He and his wife recently sold their second home, a 40-acre farmstead in upstate New York that they’d owned for more than two decades. But they’ll continue to enjoy the Grade II listed Georgian townhouse in London’s Bloomsbury (‘with a garden… f---ing gorgeous!’) that they bought 15 years ago and converted into a private home decorated with Hopton’s hand-printed fabrics, as well as work by friends, including a self-portrait by Lucas. The building used to be the offices of The Spectator magazine. Referring to a famous former editor who went on to become prime minister, Hume says gleefully, ‘Boris bonked in our front room.’

Lee also owns a terraced Georgian townhouse, which he bought three years ago in Islington, north London. He’s enjoying being back in the capital permanently for the first time since his Saint Martins days: ‘The thing I appreciate about this city is the variety… the nightlife, the street culture, the theatre, the galleries. That’s why I love it.’ As well as going to the gym and attending the ballet (his partner is the Italian dancer Roberto Bolle, an American Ballet Theatre principal), he also follows football – the Emirates Stadium is, he says, ‘not far’ from home – and recently cast Arsenal’s Bukayo Saka as a model in a campaign.

A rap on the door signals that our time is up. A few days later I head for the National Theatre, where gleaming SUVs are queuing to drop off Burberry’s guests. By the entrance, Hume’s drapes appear like sentinels, or a sort of shamrock-coloured stage curtain. Inside, as Saltburn star and brand ambassador Barry Keoghan, wearing an off-white puffer jacket, bounces around with a microphone, A-listers, including Blur’s Damon Albarn (wearing a gnomish grey beanie) and Hume’s erstwhile subject Kensit, take their seats. ‘Head for the flags – sorry, I mean, the artwork!’ an attendant says, directing me to mine.

Offset by a lilac carpet, as well as the taupe of the building’s foyer, more tarpaulins by Hume – including various brighter, box-fresh new ones, tethered in place by plastic twine – divide up the space brilliantly. With energetic edges dangling threads, their cut-outs function as peepholes, offering tantalising glimpses of other guests and, eventually, after the show begins (punctually, perhaps, for the fashion world at around 45 minutes late), the models. They wear distressed parkas with feathery organza trims and garments with perforated details inspired by Hume’s set, which, in turn, complement the odd flash of marigold in Lee’s designs. In the event, Hume’s banners don’t appear especially skull-like. One or two remind me of jack-o’-lanterns, but they seem jovial and benign. Many are not anthropomorphic at all.

Within 15 minutes the show is over and everyone scarpers, already thinking about the next fashion week, in Milan. What will happen to Hume’s tarps? ‘They’ll be folded, very neatly,’ he confirms, then packed away, taking up even more room than before. Will he ever again be tempted to chuck them out? He smiles. ‘Definitely not.’