Books of the month: From Jan Grue’s I Live a Life Like Yours to Rose Tremain’s Lily: A Tale of Revenge

Over five years, Paul McCartney talked about his remarkable back-catalogue to Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Paul Muldoon, the editor of the two-volume Paul McCartney The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present (Allen Lane). The result is an intriguing insight into the artistic process of one of the world’s greatest songwriters.

The Lyrics, featuring 154 songs, is a beautifully presented treasure trove from McCartney’s archive. It includes hand-written lyric sheets, previously unpublished personal photographs, drafts and drawings; there are even never-before-seen lyrics to an unrecorded 1960s Beatles song called “Tell Me Who He Is”. Even for non-diehard Beatles fans, it’s interesting to find out more about the people and places that inspired so many fantastic songs (and “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da”). “Money can’t buy you love”, McCartney memorably wrote, but you’ll need £75 to afford The Lyrics.

The most unusual music publication this month is Fear Stalks the Land! A Commonplace Book by Thom Yorke & Stanley Donwood (Canongate), which is a celebration of the ideas, both written and drawn, that were behind the creation of the Radiohead albums Kid A and Amnesiac. The book includes faxes, notes, scribblings and sketches that musician Yorke and artist Donwood exchanged in the run-up to the creation of two iconic albums.

A more standard music memoir is My Life in Dire Straits (Bantam Press) by bass player John Illsley. He recalls that their manager Ed Bicknell hated the name Dire Straits, telling them: “F*****g awful name… you sound like a s*** punk band.” They kept it, however, as the name summed up their lack of money when the musicians first went on the road. Illsley recalls some of their early travails, including the grubby hotels and guest houses that Mark Knopfler and his bandmates were forced to use. “In one boarding house, there was such a large hole in the wall connecting adjacent bathrooms that we could stick our heads through and brush our teeth in each other’s rooms,” he recalls.

Meanwhile, Laurence King Publishing continue their Lives of the Musicians series with a book on Prince by Jason Draper. This excellent, concise biography, by Prince expert and former Record Collector editor Draper, is full of enthralling details and anecdotes. Prince is an insightful guide to a world-conquering musician whose influence continues to shape pop culture.

In When There Were Birds: The Forgotten History of Our Connections (Little, Brown), Roy and Lesley Adkins provide an appealing social history of Britain that charts the relationship between people and birds. There is a lot of quirky information, including that pheasants have unusual powers of hearing. In the First World War, these unwieldy creatures often gave warning of approaching Zeppelins, long before humans could hear these airship bombers.

Among the recommended fiction this month is Claire Oshetsky’s debut novel Chouette (Virago Press), a highly original tale about a woman who gives birth to an owl. It’s a fable that has profound things to say about motherhood, ambition and perceptions of ability. Another novel that is full of the fantastical is Helen Oyeyemi’s Peaces (Faber), which takes its title from a poem by Emily Dickinson. Nigerian-born Oyeyemi describes herself as “quite an alienated person”, and she explores the illusory nature of tranquillity in relationships in the tale of two lovers (and their pet mongooses) on a strange train journey that forces them to confront what they mean to each other. Some of the writing is exquisite, but, overall, the novel is an acquired taste.

Those salty sea dogs in the navy have their own special language. Among the weird terminology detailed in Gerald O’Driscoll’s A Dictionary of Naval Slang (Swift Press) is the fact that sailors call people with big feet “Clampy”. The seafarers have a lot of nicknames for food, and while some are easily understandable – Ravioli is known as “Action Man Pillows” – some are mind-boggling. It’s not explained why baked beans are known as “Texas Strawberries”.

Although the Queen’s grandfather, George V, is the principal subject of Jane Ridley’s detailed biography George V: Never a Dull Moment (Chatto & Windus), there are revealing passages about his wife Mary. She died in 1953, just before Elizabeth II’s coronation. There were claims that the Queen’s old gran suffered from “kleptomania”; Ridley avoids the “off-with-your-head approach” and charitably labels as“gossip” reports that “people learnt to hide the carriage clocks and put away the Fabergé before Mary arrived”.

Finally, the Kashmir conflict should concern us all. It is a highly flammable situation, with heavily militarised, volatile borders. In the excellent Kashmir at the Crossroads: Inside a 21st-Century Conflict (Yale University Press), Sumantra Bose has written a concise and chilling guide to a precarious region, one in which China is playing a growing, dangerous role in the ongoing dispute between India and Pakistan.

Fiction from Rose Tremain, along with Jan Grue’s memoir, a biography of H G Wells and Mary Gaitskill, and a guide to Europe’s cathedrals, are reviewed in full below.

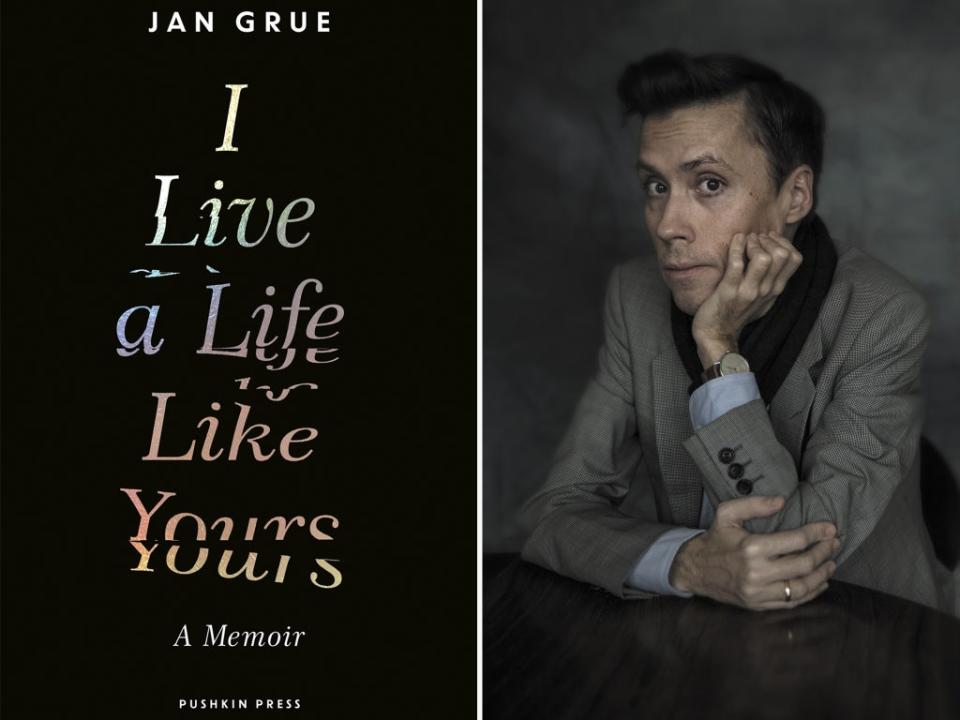

I Live a Life Like Yours by Jan Grue â â â â â

Norwegian writer and academic Jan Grue’s beguiling memoir I Live a Life Like Yours (Pushkin Press, translated by B L Cook) is a witty account of surviving in a vulnerable body, and a powerful examination of the meaning of disability.

Grue has used a wheelchair since early childhood, after being diagnosed with spinal muscular atrophy, and his book is full of absorbing reflections, everything from his musings on the type of wheelchair Peter Sellers is given in Dr Strangelove, to the former Fulbright scholar’s thoughts on art, literature, grief, identity and the concept of stigma.

Grue, a husband and father, is good company throughout and his explanation behind one of my favourite recurring moments in The West Wing is fascinating. “Some role models do exist,” writes Grue. “Although there were several things I liked about The West Wing, the best was the way President Bartlet put on his jacket. He would sling it over his head and around his back, like it was a cape and he was headed into battle.”

While the jacket trick might have looked like a gimmick, Grue said he “instinctively” knew what he was really seeing – the action of an impaired man. This was something later confirmed by Martin Sheen, when the actor revealed that he had been born under difficult circumstances, a forceps birth that smashed his left shoulder, leaving him with limited use of his left hand.

I Live a Life Like Yours, which won the Norwegian Literary CriticsPrize, is a quietly wonderful memoir.

‘I Live a Life Like Yours’ by Jan Grue is published by Pushkin Press on 4 November, £14.99

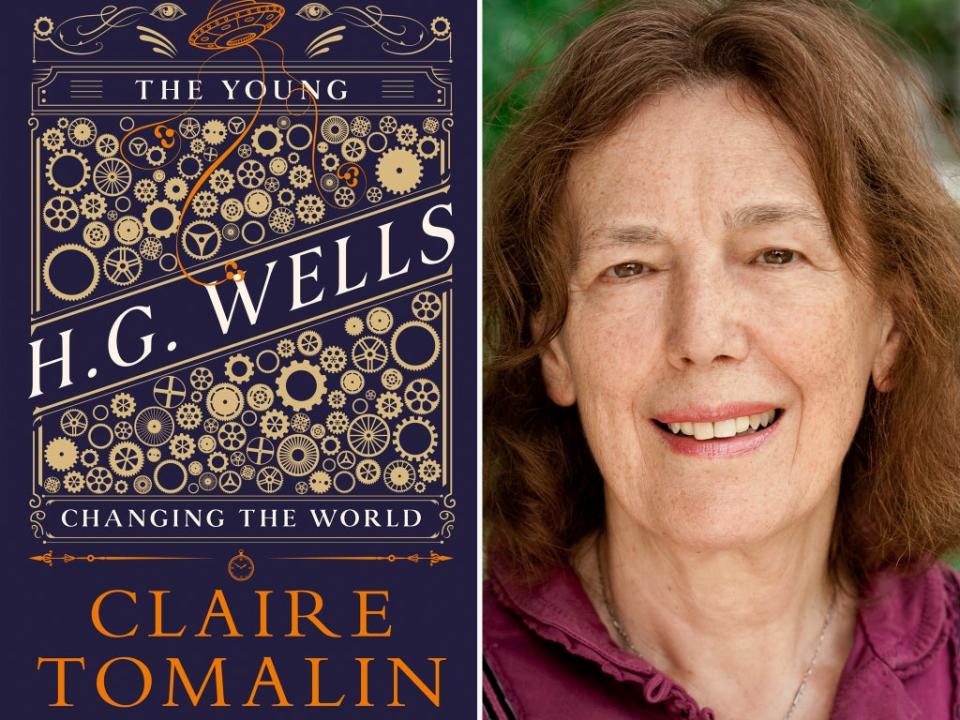

The Young HG Wells: Changing the World by Claire Tomalin â â â â â

When serial philanderer HG Wells was cheating on his second wife with Amber Reeves, he described the 21-year-old student, with whom he later fathered a child, as “slap-dash, vain, garrulous and greedy”. He was unsparing about his own flaws, too, summarising his character as “suspicious, angry, cruel, weak, vain and dishonest”.

Wells was all those things, and his action-packed, controversial life deserves the judicious, shrewd chronicler it has in Claire Tomalin, one of the best literary biographers around, as her works on Charles Dickens and Jane Austen alone demonstrated. In The Young HG Wells: Changing the World, she gives a balanced view of a man who was both dazzlingly talented and deeply flawed and spiteful.

His father, Joseph, the first bowler in county cricket to take four wickets in successive balls, played for Kent, and later failed as a shop owner. His son, impoverished and self-educated, suffered setbacks that would have broken lesser men. At the age of seven, Herbert George Wells was thrown into the air by an older boy, landed on a tent peg and shattered the tibia in his leg. As a 21-year-old teacher, he was injured playing rugby and suffered severe intestinal damage and a crushed kidney. Throughout his adult years, he repeatedly survived life-threatening lung haemorrhages, and Tomalin reprints a long, startling description of one attack, during which he feared the gushing blood would “choke me for good”.

The book has so many enjoyable facets, including his career path on the road to being an author. He hated being a draper’s assistant, excelled as a young teacher (one of his pupils was A A Milne), wrote quiz questions for the cheap newspaper Tit-Bits and worked as a book critic. Tomalin, a former literary editor for magazines and newspapers, notes drolly that Wells complained about the number of books being delivered to his home, commenting that “as well as the usual dross, he covered many brilliant books”. He judged Thomas Hardy’s Jude the Obscure as “a book that alone will make 1895 a memorable year in the history of literature”.

Wells’s relationship with his fellow authors is a key element in the biography. Tomalin details his bitter falling-out with Henry James. The American at first hailed the genius of Bromley-born Wells, who was 28 when The Time Machine was published in 1895, but dismissed his later works as coming from a writer who had “gone to the dogs”.

In the 15 years after The Time Machine – the core period covered under the banner of “the young HG” – Wells wrote 19 further novels, including the visionary The Island of Doctor Moreau, The Invisible Man, The War of the Worlds, The First Men in the Moon, A Modern Utopia, The War in the Air and The New Machiavelli. Wells was a force of nature: he wrote 7,000 words a day, travelled widely and was intensely involved in socialist causes.

Yet for all his belief in so-called advanced causes, Wells was a chauvinist. He was especially horrid to his second wife Jane, whom he dubbed “a bore” who “never starts anything or says anything I want to hear”. He derided both wives for the lack of sexual adventurousness. Despite speaking in a “squeaky voice” and possessing a flimsy body of which he was “ashamed”, he used his charm to woo and bed numerous intelligent, talented young women.

Tomalin details his sexual antics with a detached eye. She includes the story of the time he visited President Theodore Roosevelt and, upon leaving the White House, took a taxi straight to a brothel. The writer wished for a full account of his sex life to be made public, although that anecdote was not printed until 1984, nearly four decades after his death in 1946 at the age of 79.

The legacy of HG Wells lives on in his stupendously imaginative books, but Tomalin’s superb biography affords a rich account of the strange and unhappy genius behind these trailblazing works.

‘The Young HG Wells: Changing the World’ by Claire Tomalin is published by Viking on 4 November, £20

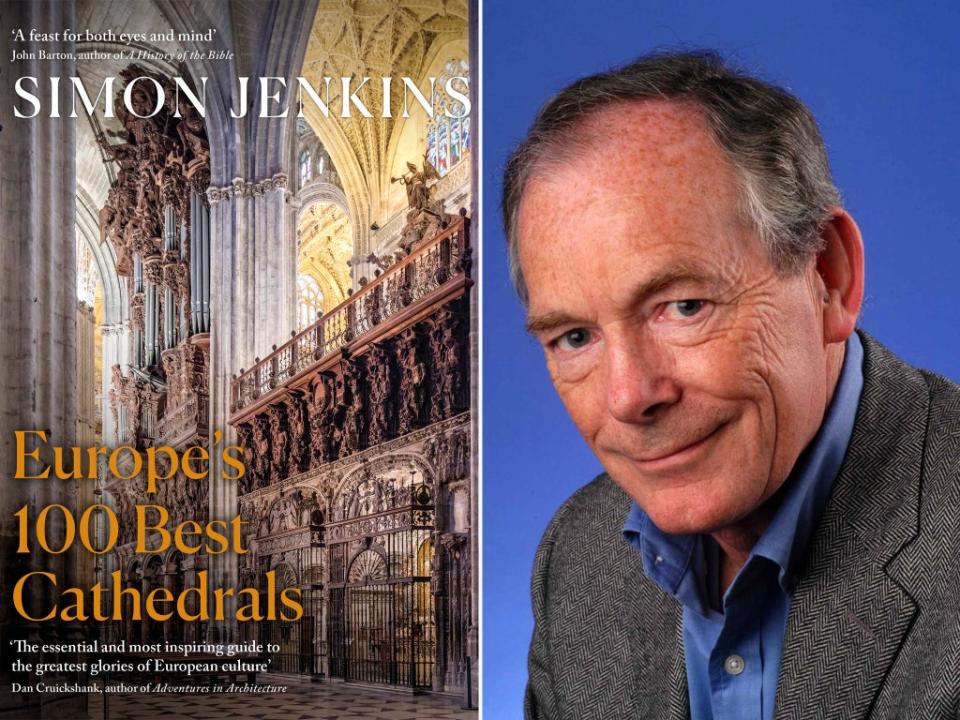

Europe’s 100 Best Cathedrals by Simon Jenkins â â â â â

“Even today, no other buildings on earth can compare with cathedrals,” writes Simon Jenkins. The beauty of cathedrals has inspired tributes and ornate descriptions from luminaries such as Robert Louis Stevenson, Charles Dickens, Thomas Hardy, William Golding and WH Auden, who evocatively captured the thrill of “cathedrals, luxury liners laden with souls/ holding to the east their hulls of stone”.

I always instinctively understood the motivation of fans who made pilgrimages to all the Football League grounds in England. After reading Jenkins’s majestic Europe’s 100 Best Cathedrals, I can understand why someone – even a non-believer – would travel round Europe to view the magnificent towers of Amiens or Tours in France, the cathedrals of Cologne or Mainz in Germany, or those in Austria, Switzerland, Italy, Malta, Spain, Portugal and Russia.

Of course, many of the world’s most awesome cathedrals are closer to home, and in his gorgeously illustrated guide to these architectural marvels, Jenkins includes informative, sharp descriptions of Great Britain’s cathedrals: Canterbury, Durham, Ely, Exeter, Gloucester, Kirkwall, Lincoln, London (St Paul’s and Westminster Abbey), Norwich, St David’s, Salisbury, Wells, Winchester and York Minster.

Although their beauty is best experienced in person, Jenkins’s book offers the chance to sit in a chair at home and quietly contemplate the loveliness of these glories of European culture, enjoying vivid descriptions of buildings Jenkins hails as “history and geography, art and science, mind and body in one”.

‘Europe’s 100 Best Cathedrals’ by Simon Jenkins is published by Viking on 4 November, £30

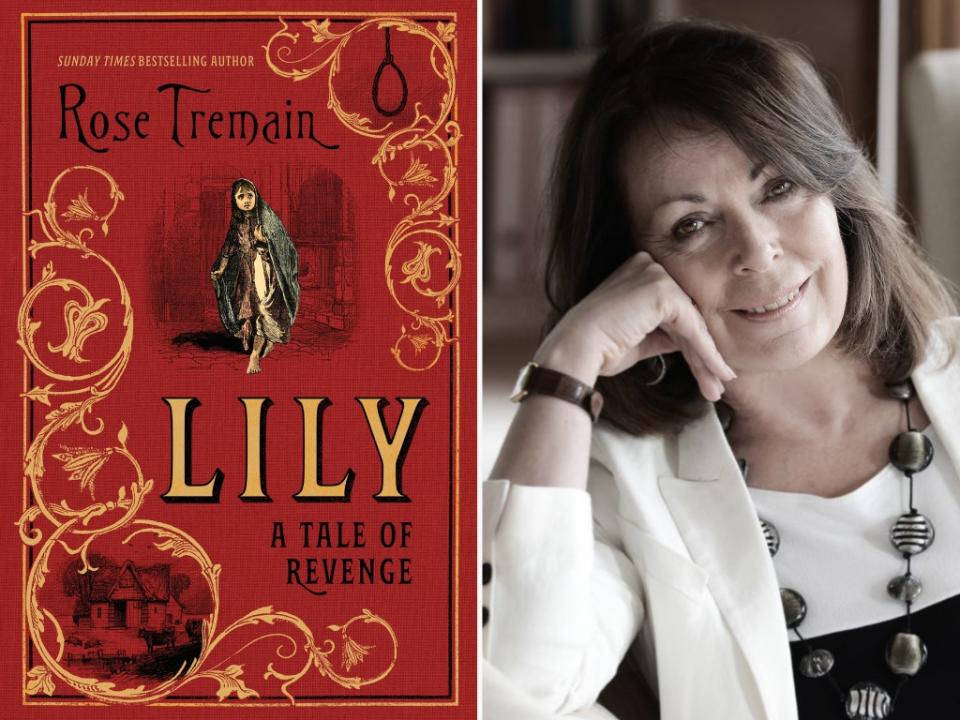

Lily: A Tale of Revenge by Rose Tremain â â â ââ

When babies were left at London Foundling Hospital in Coram’s Fields, the heartbroken mothers would leave a token behind with the abandoned child, to show remorse. On a visit to the modern-day museum there in Bloomsbury, I was shown a huge collection of these tokens, which included scraps of fabric, coins, jewellery, buttons, poems, playing cards and even a simple nut. I remember staring in grim fascination at this display of misery. The guide told me that this was the moment when most observers normally broke down in tears.

In her 15th novel, Rose Tremain imagines some of the darker ways these foundlings were treated in the mid-19th century. Her protagonist, Lily Mortimer, is rescued by police officer Sam Trench, saving her from a she-wolf who had bitten off one of her toes after she was dumped outside a park. He takes her to Coram’s Fields and the Foundling Hospital, where this spirited child, known as Miss Disobedience, is terrorised, tormented and even sexually violated by the warped Nurse Maud, a tyrant known by the children as “The Monstrosity”.

Lily: A Tale of Revenge is an engrossing historical novel. Tremain, a former winner of the Orange Prize, the Whitbread Novel of the Year and the James Tait Memorial Prize, is skilled at constructing stories, and the London she evokes is a smelly, slimy, forsaken place. Even the food she describes – Victorian delights such as tripe and onions, blackbird pâté and live eels – is pungently evocative.

Lily is a strong central character, and Tremain slowly unpeels why this lonely teenager was able to kill coldly, “without pity”, in a deft, sorrowful novel.

‘Lily: A Tale of Revenge’ by Rose Tremain is published by Chatto & Windus on 11 November, £18.99

Oppositions: Selected Essays by Mary Gaitskill â â â â â

The 2002 film Secretary was based on a Mary Gaitskill short story, an idea prompted by a report she’d seen in Ms Magazine a couple of years earlier, about a Midwest lawyer running for office who had “been revealed to have abused his former secretary by spanking her and videotaping her standing in a corner repeating ‘I am stupid’”.

In “Victims and Losers, a Love Story: Thoughts on the Movie Secretary”– one of 21 sparkling essays published between 1994 and 2021 and collected in Oppositions – Gaitskill reveals that she instantly saw the appeal of this story: “funny, horrible, poignant and gross, the misery of it as deep as the eroticism”. In the essay, she writes about the problems of having a dark, edgy story filtered by Hollywood. In her original fiction, for example, Lee’s character, played by Maggie Gyllenhaal, cries the first time she is spanked, but there is none of that turbulence in the film adaptation. Not that the author blames Gyllenhaal for this bowdlerisation. “She is a delightful and unaffected presence,” writes Gaitskill. “So pleasing that she almost redeems a character verging on total insipidity.”

Gaitskill writes with equal panache about her own life, films, music and books. In the books section, there are engrossing essays about John Updike, Joyce Carol Oates, Charles Dickens’s Bleak House and Anton Chekhov’s Gooseberries, which she neatly relates to her own experiences living in Syracuse.

Oppositions is an unsettling read, not least because of Gaitskill’s candour. In her analysis of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, she discusses her own sexual abuse as a child, when she was “molested” by a neighbour, a family friend. Yet she still reveres Lolita, Nabokov’s tale of the paedophile Humbert Humbert, admitting, “I loved it in part because I was deeply satisfied and even comforted by its rare acknowledgement of the awful complexity of the human relationship to beauty and evil, normality and evil, even love and evil.”

The essay “The Trouble with Following the Rules: On ‘Date Rape’, ‘Victim Culture’ and Personal Responsibility” is also a deeply disquieting read, not least because she examines the complexities of consent in an article in which she discusses her own “terrifying” experience of being raped. Her essay on porn star Linda Lovelace is also disconcerting. Yet what makes Gaitskill so stimulating is that she expands the way you think about something, in this case by finding a link between Lovelace’s movie Deep Throat and the 1928 silent film The Passion of Joan of Arc.

Although this sounds remarkably heavy and off-putting, I would also emphasise that Gaitskill’s writing is full of good-natured humour and wonderfully barbed wit. This is seen in her account of revisiting St Petersburg (“a chaos vector”) or dissecting a presidential campaign that featured the obnoxious John McCain (“he once called his wife a ‘c***’ in front of reporters,” recalls Gaitskill). She is especially sharp on the toxicity of Sarah Palin, who in Gaitskill’s words was “somebody who dripped with highly charged, puerile cruelty; it was there in her sneering, aggressively charming voice, in her body, in the set of her mouth”.

Gaitskill writes with such intelligence that it’s hard not to have your mind changed by the nuanced way she tackles painful ethical and intellectual quandaries, while all the time urging compassion. She is also a marvellous antidote to the modern social controversy junkie. As she puts it: “We have enough to do trying to understand and know ourselves, if we could only stop bellowing about each other long enough to try.”

‘Oppositions: Selected Essays’ by Mary Gaitskill is published by Serpent’s Tail on 11 November, £16.99

Read More

Books of the month: From Jonathan Franzen’s Crossroads to Sarah Hall’s Burntcoat

Liane Moriarty: ‘I’m sure my books are probably too white’

John Banville: ‘For 40 minutes I was a Nobel Prize winner’

Dark energy meets technical mastery in Royal Academy’s Constable show

Dressed to kill: Why gangster and fashion films have a lot in common

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm’s Mum is a devastating picture of perinatal depression – review