The Book-Makers by Adam Smyth review – bound to be brilliant

As well as the stories inside books, there are the stories behind them – tales of printers, binders, typesetters and paper-makers who are mostly unheard of. Adam Smyth, a literature professor who is also part of a printing collective, wants to do these men and women justice. Rather than go back to ancient China or dwell on obvious names (Gutenberg, Caxton), he picks out a handful of talented individuals whose lives are as exceptional as their achievements.

He begins 550 years ago, with Dutchman Wynkyn de Worde, one of the many immigrants in London who advanced English print culture. From a converted tavern in Fleet Street, he published more than 800 titles, with a pioneering use of woodblocks, an enthusiasm for Middle English literature, and a fondness for handbooks and guides. Among his odder publications was a printed birth girdle – a strip of paper to be placed over a woman’s womb during labour that sought divine aid for a happy outcome.

Smyth emphasises the role of women in book-making, among them the sisters Mary and Anna Collett, exemplars of a fashion for cutting up books with knives and scissors and reassembling them with images and additional texts. Their cut-and-paste skill in remaking Bibles into what they called “harmonies” found favour with King Charles I, who visited them at Little Gidding in 1624. The “glorious deformitie” of such efforts was seen not as sacrilege but as a reanimation of the fixed or stable text; as Smyth says, it’s a reminder that books are forever in flux. In the 18th century many “Grangerisers’” or ‘“extra-illustrators’” followed suit, expanding standard print versions to sometimes ludicrous extremes: a four-volume work could become 36 volumes with thousands of illustrations – “book madness” on a massive scale.

Two names that come up here are better known: the typographer John Baskerville and the printer (and American founding father) Benjamin Franklin. Smyth’s approach to them is shrewd rather than reverential. He praises the “radical clarity” of Baskerville’s typeface but also highlights the importance of his wife, Sarah Eaves, in running the printing side of his business. As to Franklin, a workaholic whose life was so eventful that the chapter on him is bursting at the seams, the story is as much about his lowly jobbing commissions as about books. While working on Samuel Richardson’s novel Pamela, for instance, he broke off to print lottery tickets, sheriff’s warrants and hat bills. Successful businessman as he was, Franklin couldn’t resist piety and preachiness – as DH Lawrence said: “He made himself a list of virtues, which he trotted inside like a grey nag inside a paddock.” Less virtuously, the newspaper he edited carried adverts for enslaved people.

Smyth’s tone is jaunty, but there’s no doubting the breadth of his knowledge and love of the business. He shows us what a 15th-century print works looked, sounded and smelled like; details the gruelling work with a 10lb hammer, hot animal glue and calfskin that binders carried out; describes the “vatmen”, “couchers” and “layers” who toiled in different roles in paper mills until a machine invented by the Frenchman Nicolas Louis Robert could produce up to 50 metres of paper a minute. Trade terminology is unavoidable (punch, matrix, glyph, zine) but it’s gently explained. And between the biographical portraits comes out-of-the-way information: how books used to be sold as a folded bundle of sheets, for instance, leaving it to the customer to get them bound; or how as part of its policy of dispensing with “superfluous” books (“Happely some plaies may be worthy the keeping: but hardly one in fortie”), the Bodleian Library sold Shakespeare’s First Folio cheaply in 1624, and it didn’t re-emerge from private ownership for nearly 300 years.

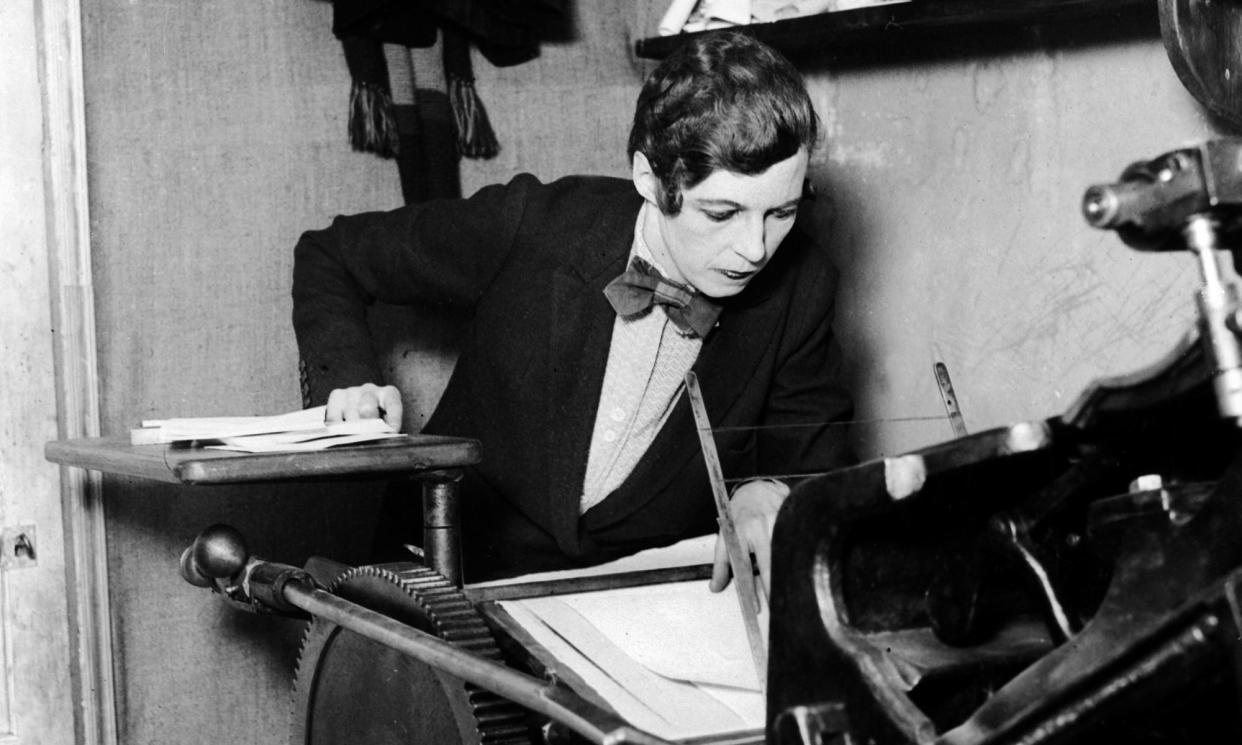

Smyth ends closer to home, albeit pre-digitally, with Nancy Cunard’s small press and the DIY “done-in-the-bedroom” publications of present day activists. It is bittier and less absorbing material but integral to his emphasis on the adaptability of the physical book and his celebration of print work done by hand. More topical, given the disappearance of public libraries today, is his chapter on Charles Edward Mudie, whose vast Victorian circulating library was a bargain for members (one guinea for town subscribers, two guineas for country – less than the price of a three-decker novel) but angered many authors, especially those whose books were not made available, among them George Moore, who attacked Mudie as “the great purveyor of the worthless”.

Mudie said that no book carried in his library should make a respectable young woman blush, though the 7.5m books he owned by 1890 included many, including Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, that a more religious-minded gatekeeper would have judged unsafe, and his distribution of British books across the world (Hardy, George Eliot, Trollope) played no small part in the establishment of English literature as an academic subject. Hundreds of thousands of readers were indebted to him, yet the venture eventually ended in bankruptcy. That’s often the way in the book business, even as books themselves adapt and endure.

• The Book-Makers: A History of the Book in 18 Remarkable Lives by Adam Smyth is published by Bodley Head (£25). To support the Guardian and Observer, order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.