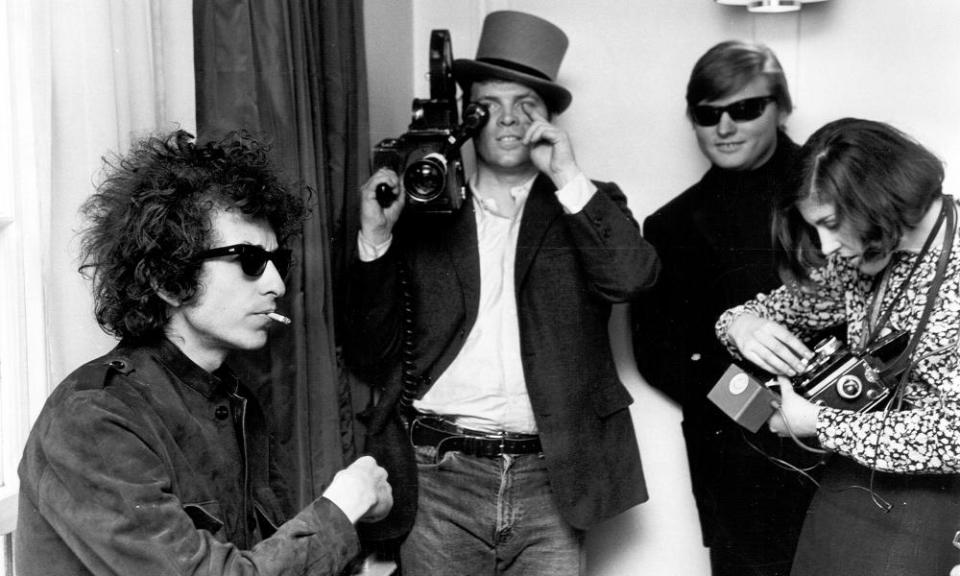

‘Blazing, incandescent’: Bob Dylan biographer Clinton Heylin on 1961-66

For three decades, Clinton Heylin has turned out an average of a book a year, about everyone from the Sex Pistols to Orson Welles. But his first love has been his longest. The 61-year-old fell for Bob Dylan when he was 12 and has now published his 11th book about the Nobel laureate, The Double Life of Bob Dylan: A Restless, Hungry Feeling. Covering Dylan’s career to 1966, it coincides with his 80th birthday.

Related: My favourite Dylan song – by Mick Jagger, Marianne Faithfull, Tom Jones, Judy Collins and more

The Guardian called Heylin at his home in Somerset to chat about his magnificent obsession. That conversation follows, edited for length and clarity.

Guardian: How did you discover Dylan?

Heylin: When I was 12, I subscribed to a monthly called Let It Rock. There was an article in the November 1972 issue about Bob Dylan bootlegs. And I’d never heard of a bootleg. I’d heard of Bob Dylan, but I was listening to T Rex and Slade.

It turned out in a city like Manchester there were four shops that sold bootleg albums. I found one in Tibb Street, in the bombed-out part of the city, which also sold German pornography. And I went, trying to find this bootleg called The Royal Albert Hall 1966.

Of course, I didn’t know that the Albert Hall wasn’t the Albert Hall – I didn’t know it was Manchester! [The record captured a concert where he was famously called “Judas” for going electric, but it was mislabeled as a Royal Albert Hall concert from nine days later.] And they didn’t have it. They had sold out. So I bought Talkin’ Bear Mountain Picnic Massacre Blues, outtakes from The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, the second album proper, released in May 1963. And then I started trying to piece it together. I read Bob Dylan by Anthony Scaduto when I was 13.

By the time Dylan played Earl’s Court in 1978, I was a fanatic. I drove my motorcycle to London. The guy next to me was taping the show. I said, “Can I get a copy of the tape?” He turned out to be the guy who organized the first two Dylan conventions in Manchester. I was introduced to a small group of fans and we set up a fanzine, which became The Telegraph, in 1981. Then, by 1991, I decided it was a high time someone wrote a proper Dylan biography – which became Behind the Shades.

Guardian: What is the thesis of your latest book?

Heylin: The last time I revised Behind the Shades was 2001. That was really before the internet got going. And it was before I’d done any serious work with auction houses and Dylan manuscripts. It was before I’d done any work with Sony Music. In the 20 years since 2001, Dylan research exploded. Ferreting out small trinkets of information is so much easier now. I always felt that there was going to be another volume but I decided there was so much material I would just start again.

There’s not that many more books left in me. I thought I’d have to do it now and it would have to be at least two volumes. I wanted the first volume to be that blazing incandescent period, that incredibly intense five years, 1961-66. Obviously the second volume will be very different because it will cover 55 years.

Guardian: What’s your favorite Dylan album?

Heylin: My favorite official album is still Blood on the Tracks, the first I bought the day it came out, 20 January 1975. I can find things in most of his albums. Maybe not the Sinatra album.

Guardian: How did you come to write the album notes for Sony’s release of the 1966 live performances?

Heylin: I was beating Jeff Rosen and Jeroen van der Meer at Legacy Records over the head. “You have all the tapes. You have the entire 1966 tour. Put it out in a box.” It took a little persuasion. But Sony went with it and it sold very well. I think they sort of felt I should do the notes, given that I’d been such a cheerleader.

Guardian: You say the biggest resources you had for the new book are the outtakes from Dont Look Back (the film of the 1965 tour) and Eat the Document (the film of the 1966 tour). What are the most interesting things you discovered?

Heylin: The really fascinating thing about that footage is the after-hours Bob Dylan. The Dont Look Back footage shows a man in crisis because he’s a star. It’s hard for people to imagine this but in America in early 1965, Dylan was not a pop star. The album before Bringing it All Back Home, Another Side, peaked at 43 right off. [When he met] the Beatles in August 1964, he was the 43rd-most popular artist in America.

Guardian: But the Beatles knew he was more important than that.

Heylin: Of course. But people didn’t know that. Freewheelin’ went to No 1 in May 1965 in England.

Guardian: So part of your thesis is that this is the first time he was a star was when he was touring England in 1965?

Heylin: Yeah. Suddenly he’s having to deal with mass media, he’s having to deal with national press, he’s having to deal with TV, he’s having to deal with enormous pressures. He’s having to deal with being chased down the street. You see him in the outtake footage in a hotel room, trying to figure out what’s going on.

There’s a great scene where Eric Clapton comes on the TV playing guitar in John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and Dylan points at the TV and says, “That’s the guy. That’s the one I’m going to be recording with.” Nobody has any idea who Eric Clapton is. I speculate in the book Dylan had been told about Clapton by Paul Rothschild, who was the Paul Butterfield Blues Band producer.

Heylin was dismissive when I asked about No Direction Home, Martin Scorsese’s film which is widely regarded as one of the greatest rock-and-roll documentaries.

“It’s not the way I would have told the story,” Heylin said. “Dylan is not in the right space to do those interviews and he looks painfully uncomfortable.”

Related: Happy 80th birthday to Bob Dylan, rock’s most prescient, timeless voice | John Harris

Actually, as the Guardian noted, “Dylan is surprisingly approachable and forthcoming.” But Heylin did praise three Dylan books that do not carry his name: On The Road With Bob Dylan by Larry Sloman, about the Rolling Thunder Review of 1975-76; Dylan –What Happened, Paul Williams’ book about the born-again period; “and of course Anthony Scaduto’s Bob Dylan – he really, absolutely blazed the trail”.

Finally, Heylin has seen Dylan perform at least 132 times – but has never spoken to him. Why not?

“Honestly,” he said, “I’ve no huge burning desire to do so. Because there’s no point unless he wants to talk to me like a human being and get rid of the Bob Dylan persona, and be just Bob. I’m not going to ask him what his favorite Bob Dylan album is. And I’m not going to ask him what his favorite Clinton Heylin book is.”

The Double Life of Bob Dylan is published in the US by Little, Brown