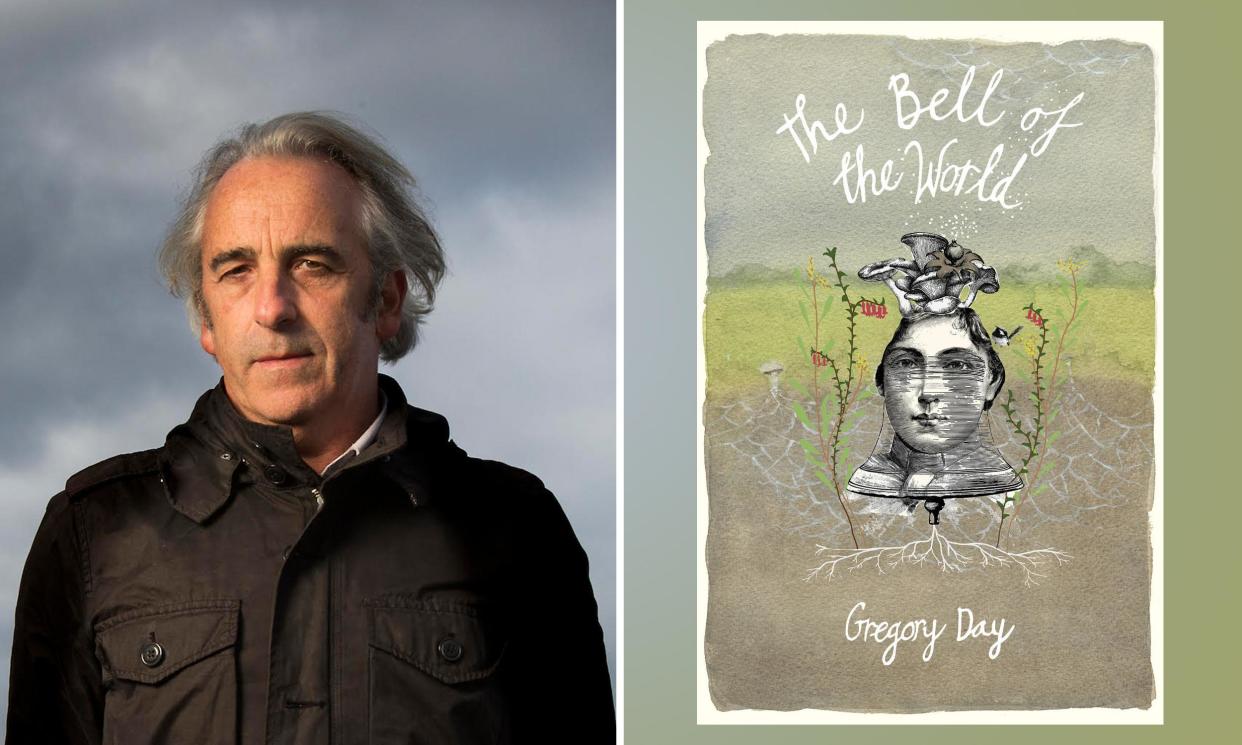

The Bell of the World by Gregory Day review – a mellifluous crescendo of Australian nature writing

Gregory Day wants us to listen. Not to the bells of civilisation – the colonial pealing that keeps our trousers up, shielding us from our true beastly selves – but to the cacophonous medley of the land itself. The novelist, poet and essayist, whose accolades include the Patrick White Literary award and a Miles Franklin shortlisting, has a long history writing about the symbiotic relationships between place, nature and language. The Bell of the World is the crescendo of these preoccupations.

Set in the early twentieth century in post-federation, colonial Australia, the novel follows Sarah Hutchinson, a young woman travelling to live with her uncle Ferny on his property in Ngangahook (a fictional town set among bush country south of Geelong). From a wealthy settler family, Sarah lives an unsettled existence after her parents’ acrimonious divorce, a forced exile to an English boarding school, and a brief excursion in Rome. She is adrift in the world, uncovering “new, almost astonishing levels of emptiness under the desolate appearance of things”.

Related: Funny Ethnics by Shirley Le review – a second-generation migrant wrestles with longing and belonging

Prior to meeting Ferny, however, Sarah encounters the “place of the drama of her healing” in the isolated countryside home of a family acquaintance, an Indigenous Australian woman named Maisie. During several weeks under her care, she experiences a gradual yet cataclysmic metamorphosis engendered by the “hushed immensities” of the vast Australian outback.

“I found a great light was breaking in my mind,” she later describes to her uncle, an avant garde autodidact who acutely shares and nurtures her experience. Day’s lyrical prose does great justice to this “long clench releasing”, a chrysalis emergence of Sarah’s creative osmosis with the land.

While Sarah and Ferny live an intimate life on the farm, authorial peregrinations on humankind-nature relations largely permeate the novel, though several events offer plot. One is the epic hewing together of Joseph Furphy’s Such is Life and Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, a springboard off which Day delves into the rich synaptic connections of creativity, identity and place. Another is the Ngangahook townsfolk’s desire for a village bell, something to “clear invisible arteries of the air”, which Sarah and Ferny oppose. Nature’s silence offers its own aural tapestry, they contend, with “each small earth-flower [being] a bell of its own”.

The novel’s incantatory yet challenging prose makes flaneurs of its readers, leading us down innumerable warrens of evocative natural imagery and sinuous thought. It is heart-sleevingly earnest and sometimes overwritten, but often it is hypnotic, eschewing read-by-numbers storytelling that deadens much contemporary Australian fiction. It is also resplendent with literary allusions and encyclopaedic ecological knowledge. A “prepared” piano features throughout, Sarah’s “bush-machine” with strings festooned with remnants of “gumnuts, bark, sturdy leaves, river flints, pieces of kangaroo and parrot bone”. It’s a discordant, inside/outside blend, a richly hybridised music about place. Day’s writing feels no different.

Related: How to be Remembered by Michael Thompson review – a proudly earnest first novel | Bec Kavanagh

The Bell of the World repeatedly returns to words and expression, evoking both their power and innate limitations. “All language is but a sobriquet”, Sarah remarks, a circumnavigation of an unnameable essence. This “deeper wealth”, nature’s own ineffable vocabulary, is the narrative’s verdant undergrowth. In Becoming Animal, David Abram, an American ecologist writes how language for traditionally oral peoples, “is not a specifically human possession, but is a property of the animate earth, in which we humans participate”. The novel’s keen attentiveness to this aural storytelling, with probing ruminations on the colonial mind’s struggle to perceive beyond the human-centric, is one of its most intriguing aspects.

In response to the climate crisis, more generative, critical ecofiction is emerging. Australian author James Bradley writes how such work is extending beyond the elegiac: “it prompts us to rethink our relationship with the natural world”. That is the effect of this narrative’s mellifluous song of “emotional geography”, to use a term of Day’s. It feels like the fictive culmination of the author’s nonfiction collection Words Are Eagles, which he describes as an attempt “to understand how best to express, or match, with written language my feeling for the place where I live”. But also how he, a non-Indigenous writer trying to connect with the land, grapples with the “ongoing challenge of how to be here as a human being”.

First Nations history, cultures and languages are familiar touchstones of Day’s work, as well as his life (with elder permission, the author for years taught Wadawurrung language to children at his local primary school). This influence is recognisable in the way the novel implores us to harmonise with nature’s resonance, to be receptive to “the ur-tones to which all languages aspire”. It’s also there in the novel’s appreciation of the truths of Indigenous belief systems and how they inform identifying with and caring for country. Aboriginal perspectives only skirt the peripheries of this narrative, however, with limited interrogation of land dispossession or colonial inheritance.

The Bell of the World devotedly sews the fibral connections – as if a rhizomic root system or the branching filaments of mycelium – between humankind and the natural world, of which we are “both, both, both: both, both and Both again”. Some may recoil from Day’s effort, with its digressive flowerings and circuitous philosophising. But like the bemused listeners of the chimeric melodies of Sarah’s bush-machine, we’d be foolish to block our ears.

The Bell of the World by Gregory Day is out now through Transit Lounge