April showers – and other myths about the British weather

“When April with her showers sweet”, wrote Chaucer. “April is the cruellest month,” added TS Eliot.

April can go back where it came from, suggests me.

After the winter we’ve just had – and, to be honest, the autumn, and what passes for early spring – the last thing anyone needs is a “traditional April”.

But is it actually true? According to the Met Office, December is the wettest month of the year with a 1991-2020 average of 127.19mm. April, over the same period, averaged just 71.73mm.

I’ve always suspected “April showers” are wishful thinking. We hope – against hope – that the rains will pass soon and not become perma-drizzle. Also, we stay indoors in December because it’s supposed to be grim. Long, lighter days and blossoms draw us outside around now – and it’s spiteful of the weather not to match our optimism.

We specialise in indirection and euphemism in the UK, especially where it concerns precipitation. “Unsettled” is forecaster-speak for rain. “Changeable” means rain, eventually. “Unstable” means rain, as does “low pressure” or “complex” or – come summer – “unseasonable”.

The English dictionary has a host of other evocative words: mizzle, smirr, downpour, spitting, chucking, slinging, throwing it down. Welsh has at least 25 words of its own. Shower? How about flist, pilmer, haster, haud, plash, perry, land-lash, and gosling blast?

Is this deluge of words anything other than the rain-weary British trying to make the best of a bad thing?

“It was cool and damp,” notes Paul Theroux, boarding the train to set off around the entire coast of Britain in The Kingdom by the Sea (1983). “The weather forecast was ‘scattered showers’ – it was the forecast for Britain nearly every day of the year.”

Did we invent all the near-synonyms to make rain seem more interesting? Or less irritating, at least?

Ducks, droughts and gardens aside, rain is generally understood to be bad weather. It makes outdoors activities unpleasant or unviable. It’s not so much the crackly, sweaty waterproof clothing or the easy-to-misplace inside-out brolly as the trudging along with one’s head bowed towards the floor. The very posture of existential despair. Bow too far and the rain pours down the back of your neck. You live without seeing the world; rain-blindness. I bet Icelandic has a word for that.

Rain killed off the Great British Holiday. “No rain in Portugal,” declares a 1954 promotional bill. “But tourists pour in.” We’d all got caught out by posters promising Sunny Devon and Suffolk for Sunshine; there were even sunny cartoons of Aberdeenshire. From the Seventies, people swapped summer showers for certain sunshine in Spain and Greece.

The Lake District needs constant refills. An average of 16mm of rain fell every day in February 2020, the highest month-long washout on record (and it was a leap year). Fell walking in constant rain seems masochistic. Yet, when I look back on my earliest independent adventures – hitchhiking trips from home near St Helens to “wild campsites” (i.e. rich people’s gardens) in the Lakes – I remember the whole experience, including breaking camp in the night due to flooding, with immense fondness.

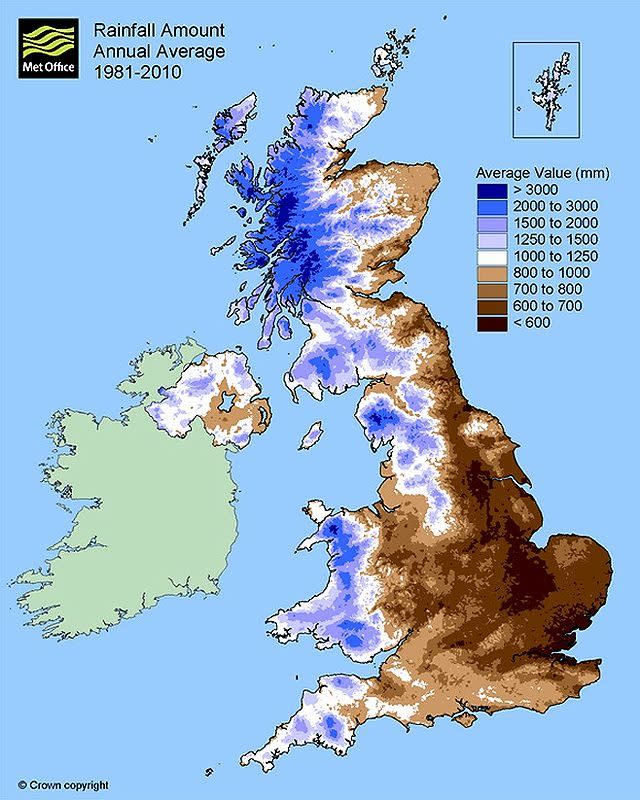

The west is, famously, wettest. That top corner, from Ulster to the West Highlands, is almost always hidden behind a mass of bubbling blue on TV forecasts. What is striking, though, is the competition among places in the UK claiming to receive the greatest quantity of rain. The internet is awash with them, from Seathwaite in Cumbria to Martinstown in Dorset to Fort William to spots all over Wales – including Cardiff, Crymych, Capel Curig and Eglwyswrw. I can vouch for the wetness of the northern half of Wales; my family holidays were all in Rhyl, Prestatyn, Colwyn Bay and Llandullas; I recall static caravans with views over the shore – the windows trickling and smeared with rainfall.

The Met Office website has a useful map of the rainiest places. Dartmoor, just about all of Wales and western Scotland all have dark blue bits – meaning more than four metres per year fell on average between 1981-2010. The Pennines and all other high places are violet – the next category down. Extreme statistics are also given, corroborating that, indeed, Martinstown was rainier than any other town ever for one day in 1955, while Crib Goch on Snowdon got the most rain over a month, in 2015.

Preston had the wettest five minutes on record – 32mm on 10 August 1893. Monsoon-type showers seem to be more frequent now, which could be down to climate change or, equally, to my imagination.

But why the competition to be wettest – and why does the Met Office know we’d all be put out if we didn’t know who got soaked the most, most often, and when the worst year was in such and such a place?

Is it weather-romanticism? Rain turns plain scenery into something quite beautiful. See Simon Buckley’s photograph of Manchester’s Deansgate in the rain if you need evidence of rain’s transformative power.

Stunning photo taken this evening in Manchester. Yes it's raining, no it's not the 1940s...

Photographer Simon Buckley of @NotQuiteLight pic.twitter.com/CVWbO3Ixr7— Dave Haslam (@Mr_Dave_Haslam) August 1, 2019

But perhaps it’s deeper than that. Melissa Harrison, who penned a whole book on the subject, notes that we respond instinctively to the sensation of rain on our skin, and on seeing it enliven streams and “baptise” dry soil. She comes even closer to the meaning of rain when she asserts: “And there’s something else that rain gives us; something deeper and more mysterious, to do with memory, and nostalgia, and a pleasurable kind of melancholy.”

We humans are changeable, unsettled and sometimes miserable. Rain reassures us that our troubled mind is part of nature.

It defines this country more than any other weather type. It’s our identity, our home, our childhood fun and our first holidays. Once upon a time we couldn’t fly away and escape it; in this soggy-looking spring of 2024, we might well have to our renew our relationship with rain. Let it come down! Let it pour!

Is Britain really so rainy compared to other countries?

Colombia and Brunei fight it out online for the title of world’s wettest country. Of course regional variations mean it’s never wet all the time all over. López de Micay in the north of Colombia has a reported – and disputed – annual precipitation of 12,892.4 mm (508 in).

According to at least one source, Bergen in Norway has secured the number one spot as the rainiest city in Europe. It receives 1,958mm (77.1in) of rainfall per year, or 163.2mm (6.4in) per month. On average there are 231 days per year with more than 0.1 mm (0.004 in) of rainfall.

According to Guinness World Records, the place with the highest average annual rainfall is the village of Mawsynram in northeastern India, which receives nearly 12,000mm of rain per year. Mawsynram is high up in India’s Khasi Hills and is directly in the path of warm, moist air swept in from the Bay of Bengal. Most of Mawsynram’s rain falls during its monsoon season, which lasts from around April to October every year.

Guinness also says Mount Waialeale in Hawaii has the most rainy days, with up to 350 rainy days per annum.

Argyllshire in Scotland – the wettest region in the UK – gets a mere 2,274.9mm of rain. But Met Office hill stations have recorded much higher numbers. The UK rain gauge in its archive with the highest average annual rainfall total is Crib Goch (Gwynedd) with 4,635 mm of rain followed by Styhead (Cumbria) at 4,562 mm.

Is April really the wettest month?

No. December is the wettest month of the year with a 1991-2020 average of 127.19mm. April has an average of 71.73mm for the same period.

The saying “March winds and April showers bring forth May flowers” dates from 1886, though the idea of April being rainy goes back centuries.

The jet stream – which ships in showers – is notoriously fickle. Sometimes it gets lodged in the north and we have dry Aprils.

Is Manchester really the wettest city in Britain?

No. South Glamorgan (Cardiff) has a slightly higher total of annual rain accumulation. For 1991-2020, the former had an annual average of 1,177.81mm of rain. Manchester had 1,087.14mm.

Note though that when it comes to the number of rainy days, the Cardiff region had 201.93 and Manchester 214.18. The former has a higher number of days with greater rain accumulations.

Is the West really wetter than the East?

Yes.

The Pennines of Northern England, the Welsh mountains, the Lake District and the Highlands of Scotland create a rain shadow that includes most of the eastern United Kingdom, due to the prevailing south-westerly winds.

We have Atlantic rainforests to prove it. Dartmoor, west Wales and Wigan are, in this respect, akin to southern Chile and British Colombia.

Does the sun ever shine on Northern Ireland?

Occasionally, but the country sits in the central track of low pressure systems and is consequently the butt of high winds and oceanic weather. In the north and on the east coast, particularly, severe westerly gales are common. Above the 800-foot (245-metre) level, distorted trees and windbreaks testify to the severity of the weather.

Is the British summer actually dry and sunny?

Yes-ish. In general, places in the east and south of the UK tend to be drier, warmer, sunnier and less windy than those further west and north. These favourable weather conditions usually occur more often in the spring and summer than in autumn and winter.

Oliver Claydon of the Met Office adds: “One stat that might be of interest is that May is statistically drier than the summer months for the UK.”

The relevant stats are: May – 70.98mm, June – 77.2mm, July – 82.48mm and August – 93.73mm.

“One thing to be aware of here though is that in the summer months you can get considerable amounts of a monthly rain total in just one event with a heavy downpour or thunderstorm, while in May the monthly total might be more spread out.”