This is what ancient humans REALLY looked like

Back from the dead

Courtesy of the Catholic University of Santa Maria

History books try to tell us what life was like thousands of years ago, but they struggle to build up a visual picture. Pay a visit to a museum and you can stare your ancestors in the face – sort of. Many museums display highly realistic portraits of ancient people, from facial reconstructions of prehistoric humans to ancient Egyptian 'mummy portraits' and Pompeiian frescoes.

Read on to meet people who lived and died many years ago, from Neolithic labourers to the so-called 'Inca Ice Maiden'...

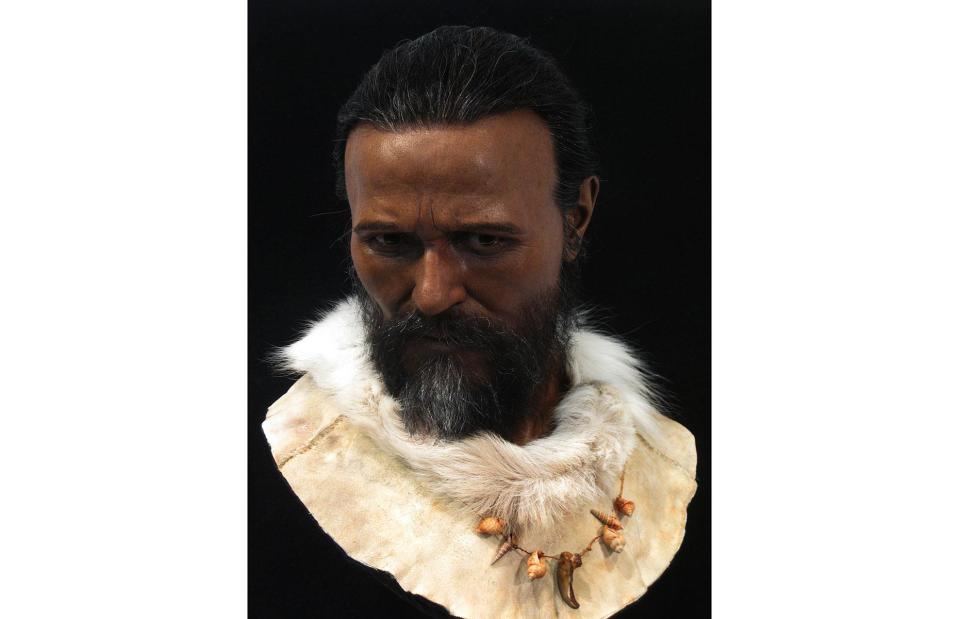

Bust of Krijn, Doggerland, Netherlands

BART MAAT/ANP/AFP via Getty Images

This young Neanderthal man once roamed Doggerland, a drowned prehistoric land just off the coast of the Netherlands. Using a single piece of his skull – an undereye bone roughly 50,000-70,000 years old – paleo-artists constructed this lifelike bust of him. Krijn, as he’s better known today, had a bump above his right eye (actually a small, benign tumour), enjoyed a meat-heavy diet and had a strong, sturdy build.

Cro-Magnon man, Dordogne, France

Courtesy of Oscar Nilsson

One of the first anatomically modern humans to settle in Europe, the man depicted in this facial reconstruction shows what some of our homo sapiens ancestors looked like 40,000-10,000 years ago. The skeletal remains of this prehistoric man were discovered in the Abri Cro-Magnon rock shelter in Les Eyzies, France, and were brought to life for the Royal Pavilion and Museums, Brighton. These early modern humans lived alongside Neanderthals.

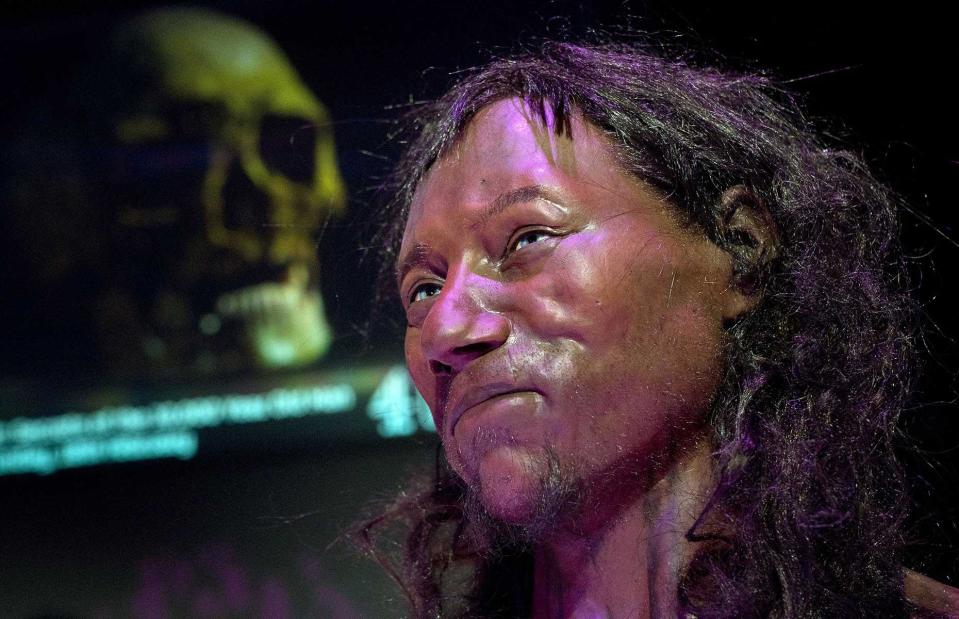

Bust of Cheddar Man, Somerset, England, UK

JUSTIN TALLIS/AFP via Getty Images

The oldest complete human skeleton ever found in Britain, Cheddar Man lived and died around 10,000 years ago, at a time when Britain was still physically connected to the European continent by land. The remains of this Mesolithic hunter-gatherer were recovered from Gough's Cave in Cheddar Gorge, Somerset in 1903, and in 2018 scientists working with TV's Channel 4 measured and scanned his skull to recreate what he looked like. He had dark skin, pale-coloured eyes and dark brown hair. Fun fact: Europeans were lactose-intolerant at this time.

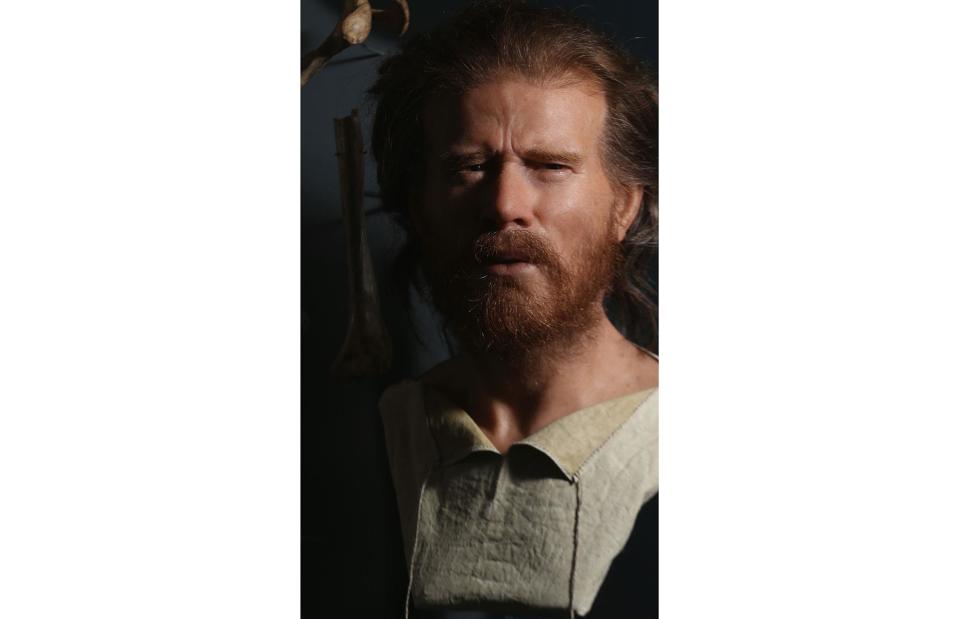

Ludvig, Motala, Sweden

Courtesy of Oscar Nilsson

Using an 8,000-year-old skull and genetic evidence, archaeologist and sculptor Oscar Nilsson reconstructed this Mesolithic man – dubbed 'Ludvig' – with a pale complexion, blue eyes and long brown hair. The skull was discovered along with nine others in Motala, and Ludvig's was curiously impaled on a wooden stake, making it the first find of its kind. This hunter-gatherer was in his 50s when he died and had a prominent one-inch wound on the top of his skull, however the injury had showed signs of healing so may not have been what killed him.

Stonehenge Man, Wiltshire, England, UK

Matt Cardy/Getty Images

Based on a 5,500-year-old skeleton found in the Stonehenge area, this facial reconstruction dubbed ‘Stonehenge Man’ is believed to show what one Neolithic man looked like thousands of years ago. It’s thought that he was born around 3000 BC in Wales, moved to Stonehenge at three years old and died between the ages of 25 and 40. Interestingly, his remains showed little sign of manual labour and he was buried in an elaborate tomb. Experts gave Stonehenge Man muscular features, hazel eyes and dark brown hair with hints of ginger, to reflect his (likely) Celtic origins.

Whitehawk Woman, Brighton, England, UK

Courtesy of Oscar Nilsson

The skeleton of this Neolithic woman was found in the ancient burial mounds of Whitehawk Hill, Brighton's oldest monument. This incredible facial reconstruction depicts what Whitehawk Woman may have looked like while she was alive, sometime between 3650 and 3520 BC. It's thought she grew up near Wales, travelled a great distance to East Sussex and was between 19 and 25 years old when she died. It's thought the Whitehawk Woman may have died during childbirth, as the remains of a foetus were found in her pelvic area.

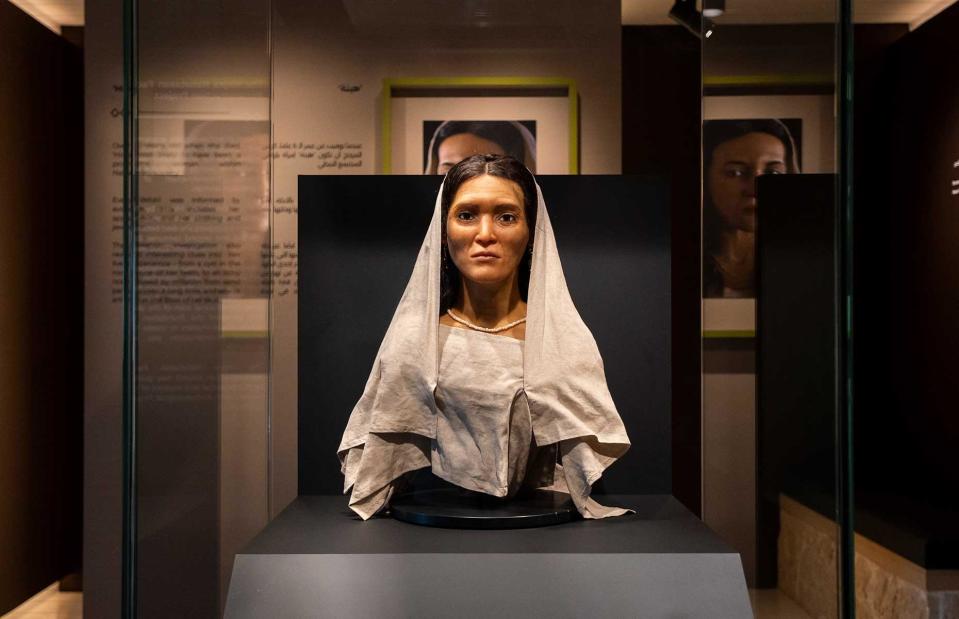

Bust of Hinat, Hegra, Saudi Arabia

Courtesy of Commission for AlUla

Some 364 miles (586km) south of Petra (Jordan's iconic Nabatean settlement) lies the 2,000-year-old city of Hegra – the second city of the Nabatean kingdom. In 2008, archaeologists discovered an ancient rock-cut tomb containing human remains, with an inscription (dated to 60-61 BC) above the tomb's entrance dedicated to a woman called Hinat. Analysis of the skeleton believed to be Hinat revealed she was between 40 and 50 years old at the time of death, stood at five feet three inches (1.6m) tall and was of medium social status. Following expert advice and artistic interpretation, this reconstructed bust depicts Hinat wearing replicated jewellery and woven linen authentic for the time.

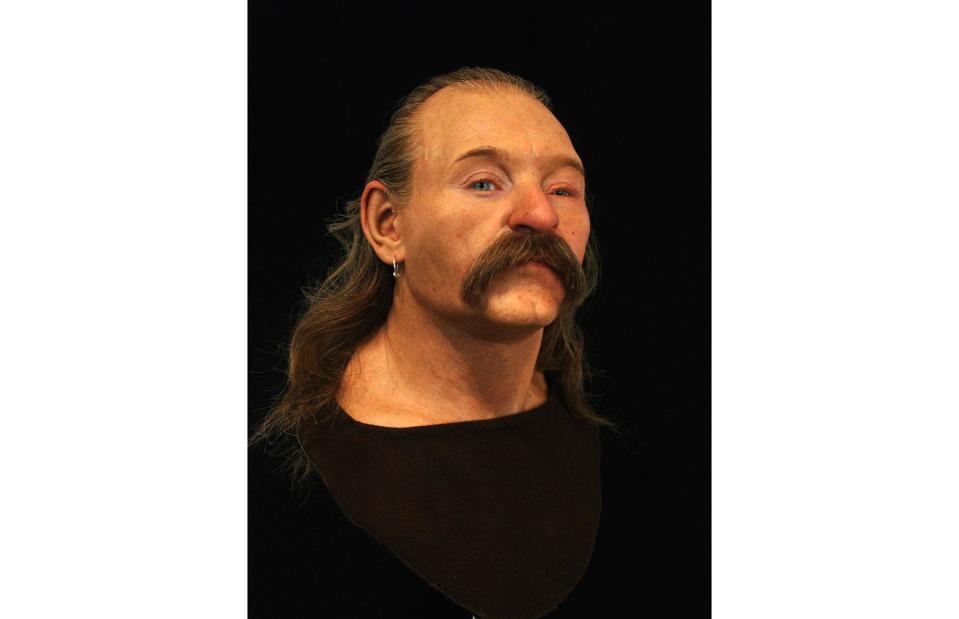

The Stafford Road Man, Brighton, England, UK

Courtesy of Oscar Nilsson

With his strong moustache and long hair, this Anglo-Saxon man lived around AD 550. Discovered in a grave in Brighton, archaeologists learnt that he was over 45 years old, stood at five feet nine inches (1.75m) and likely died of dental issues due to multiple mouth abscesses. They also found weapons in his grave, suggesting he was a warrior.

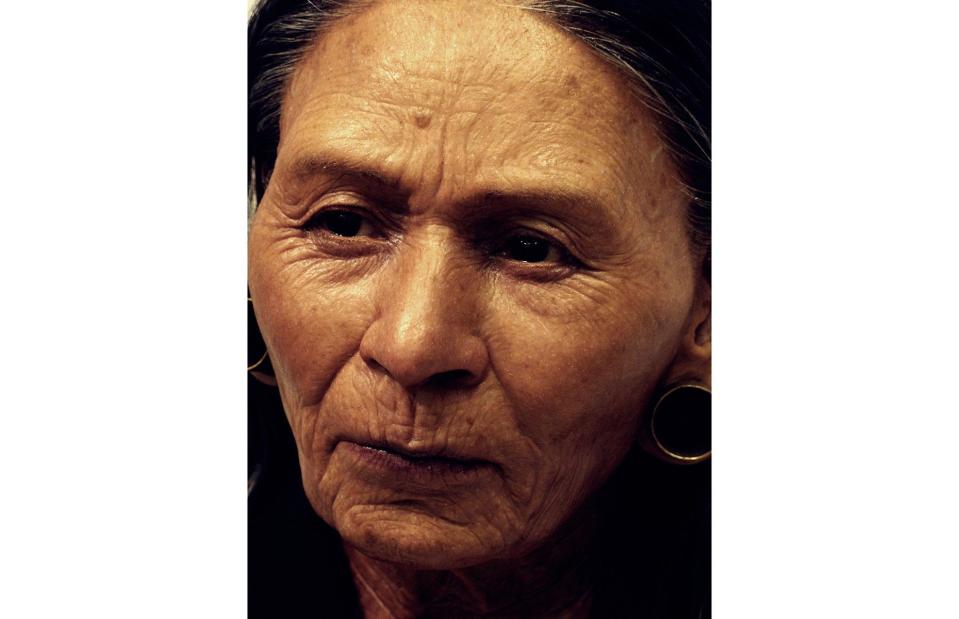

Huarmey Queen, Lima, Peru

Courtesy of Oscar Nilsson

In 2012, the skeletal remains of this Wari noblewoman were discovered in a pyramid mausoleum north of Lima, buried in a private chamber. The Wari people lived in this Peruvian region between AD 700 and 1000, long before the Inca rose to power. She lived around 1,200 years ago and died around the age of 60 – this detailed facial reconstruction is based on a digitised scan of her skull. Dubbed the Huarmey Queen, she wears earrings that are an exact replica of the ones found in her tomb.

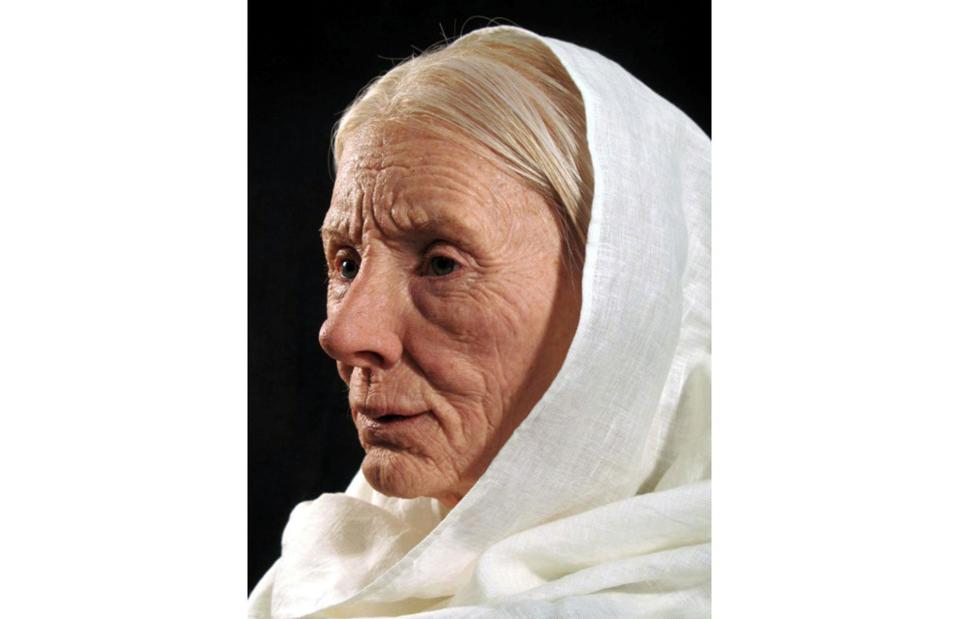

Estrid Sigfastdotter, Stockholm, Sweden

Courtesy of Oscar Nilsson

Pictured here is Estrid Sigfastdotter, who was born in the 11th century to a powerful, wealthy family. Because of the high number of runestones with her name on them (these were usually dedicated to powerful men), experts believe Estrid was an influential woman and likely the head of her family. While life expectancy at the time was 35 years, Estrid lived until around the age of 80, the age she's depicted as in this facial reconstruction housed in the Stockholm County Museum.

Bust of King Richard III, Leicester, England, UK

Dan Kitwood/Getty Images

This bust of King Richard III – whose remains were found buried beneath a modern-day car park in Leicester in 2012 – is based on a scan of his skull. DNA results showed that the 15th-century English king had a 96% probability of having blue eyes. Unlike Tudor-era portraits of the king, which commonly depict him as having dark hair, the DNA results suggested that he had a 77% probability of having blonde hair.

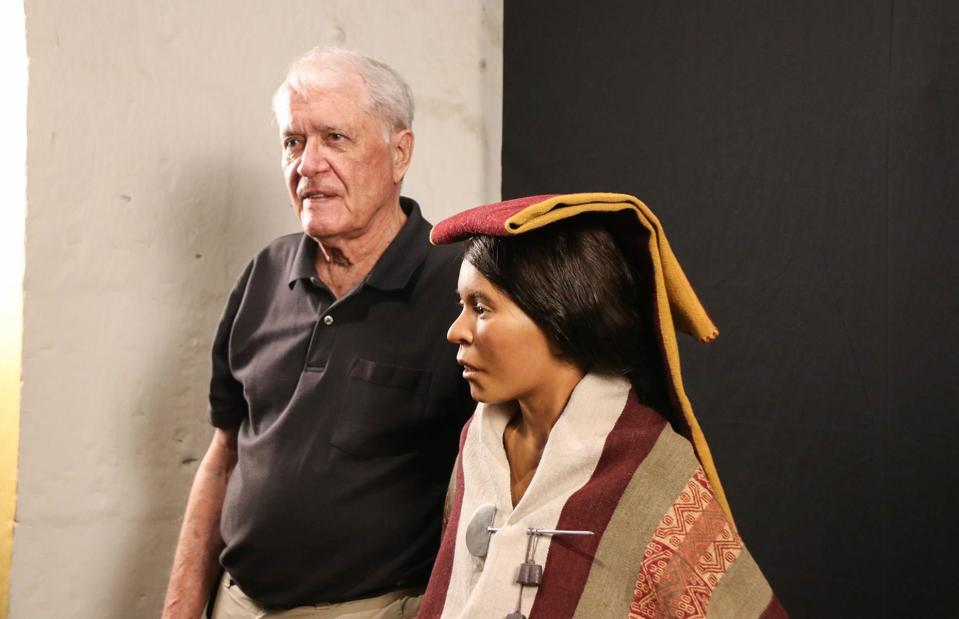

Inca Ice Maiden, Arequipa, Peru

Courtesy of the Catholic University of Santa Maria

In 1995, archaeologists discovered the frozen mummy of a teenage Inca girl on Ampato volcano, high in the Peruvian Andes. The child – known as 'Juanita' or 'the Inca Ice Maiden' – is thought to have been ritually sacrificed following a volcanic eruption some 500 years ago. Such a sacrifice would have brought honour to her family, and she would have been worshipped in her family for generations. In 2023, a team of Peruvian and Polish scientists unveiled a reconstruction of her face in the Catholic University of Santa Maria in Arequipa, using DNA studies, body scans, skull measurements and ethnological characteristics to inform their research.

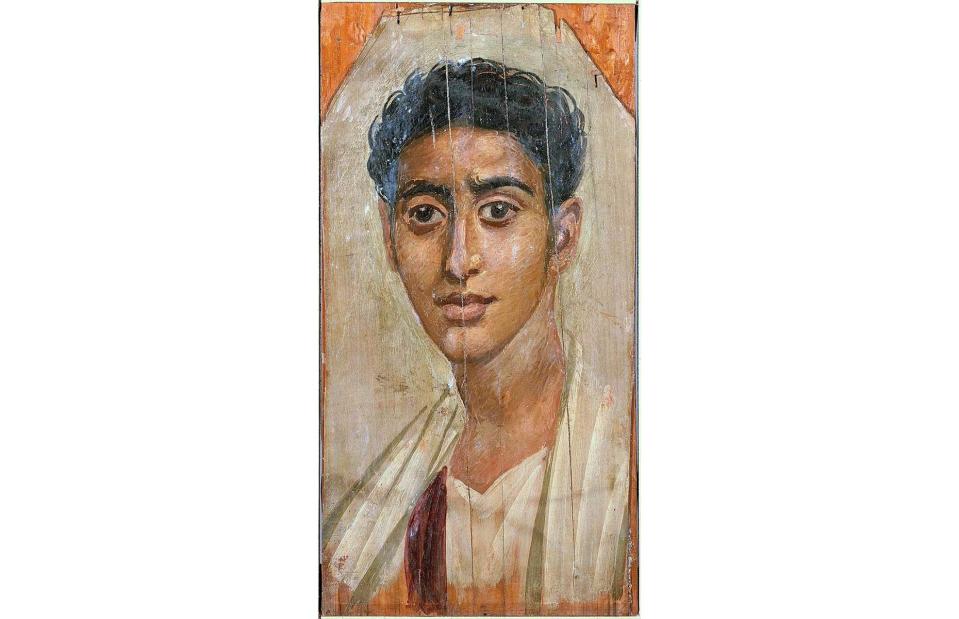

Mummy portraits, Fayum, Egypt

MET Museum/Public domain

When Egypt was part of the Roman Empire, there was a fusion of old traditions and new trends, like these 'Fayum portraits' (named after the area south of Cairo where they were frequently found) which became popular in the 1st to 3rd centuries AD. Around 900 are known to exist. It's thought that these painted panels were originally displayed at the subject's house while they were still alive, before being transferred to their mummy once they had died. They were placed over the mummy's face and secured with linen bandages; pictured here is a mummy with a typical Fayum portrait, dating to AD 80-100.

Venture inside Aten, Egypt's answer to Pompeii

Mummy portraits, Fayum, Egypt

World History Archive/Alamy Stock Photo

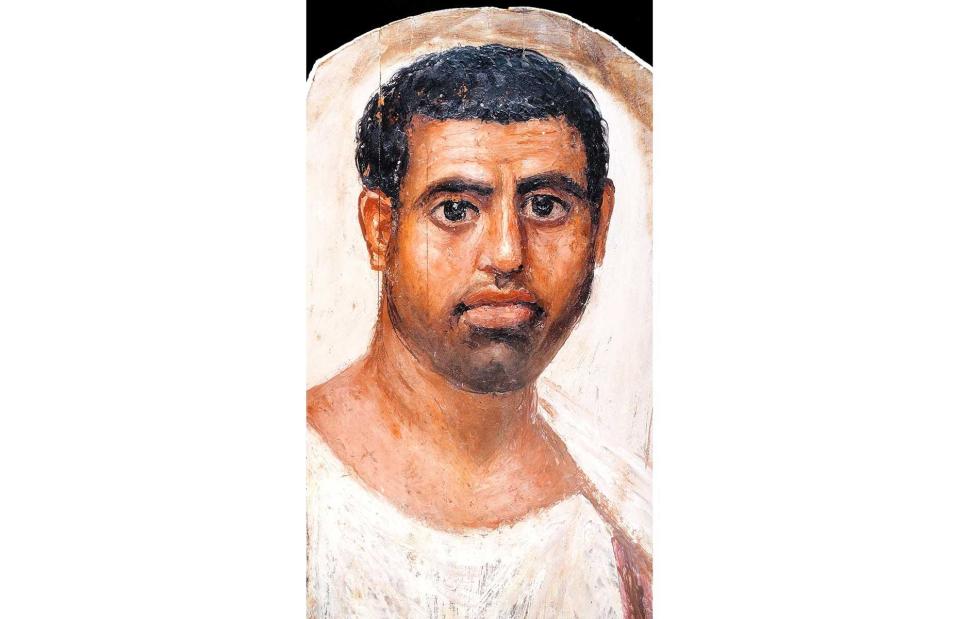

In this portrait at the British Museum, the artist has used encaustic paint (an ancient Greek technique where beeswax is mixed with pigments) to create this Fayum portrait of a man wearing a white tunic with a purple stripe. The paint is unusually thick and, in places, has been applied with fingers. With his tightly curled hair and rounder face shape, the man looks a little like the Roman Emperor Titus (AD 79-81), who reigned around the time this mummy portrait was made.

Mummy portraits, Fayum, Egypt

MET Museum/Public domain

We’re instantly drawn to this young woman’s large eyes, complemented with thick eyelashes. She wears a gilded funeral wreath – a typical funerary accessory in ancient Greece and the Roman Empire – which the artist applied using thin gold leaf. Dating to AD 90-120, the Fayum portrait’s background was originally gilded too, which, according to the MET Museum in New York, reflects "her divine status".

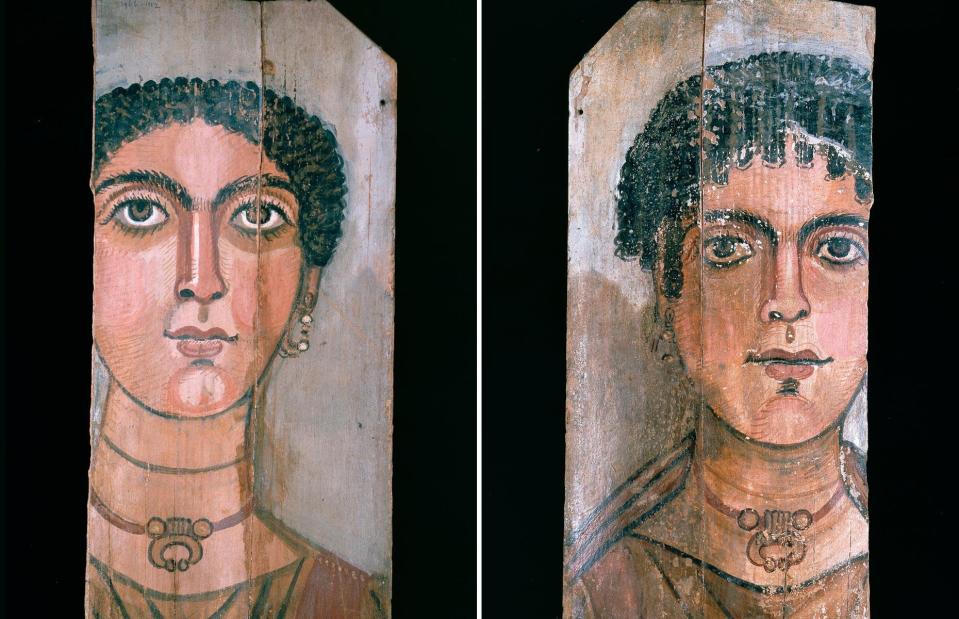

Mummy portraits, Fayum, Egypt

Ashmolean Museum/Heritage Images/Getty Images

Dating to AD 100-130, this is a rare example of a double-sided Fayum portrait, now in the collection of Oxford University's Ashmolean Museum. While the subjects don’t look much alike, it’s thought that the artist has indeed depicted the same person, as they have similar facial features, jewellery and black hair tied in tight curls. The artist used encaustic paint on a limewood panel to create this one-of-a-kind mummy portrait.

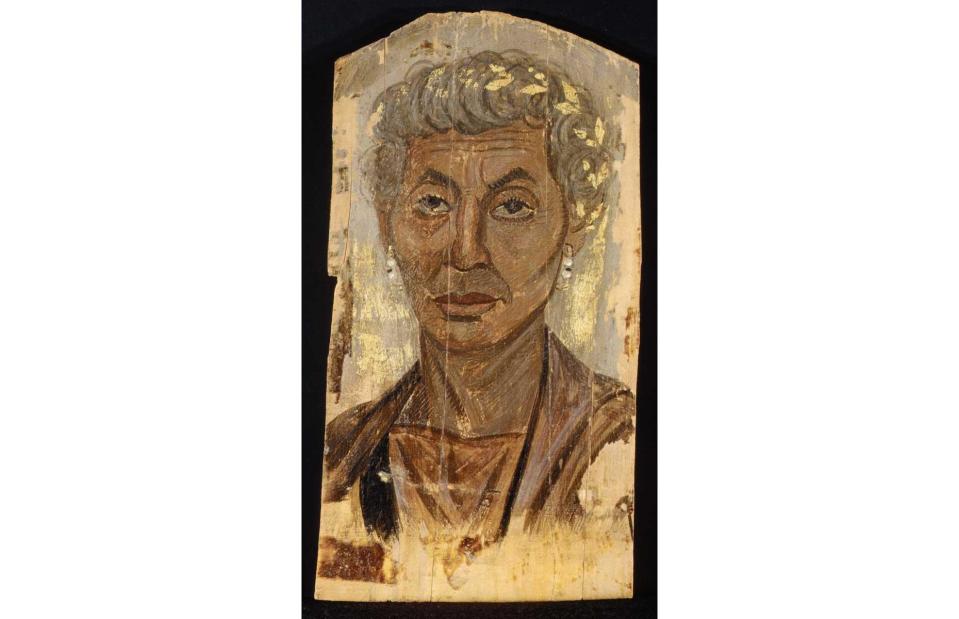

Mummy portraits, Fayum, Egypt

MET Museum/Public domain

This Greek-style Fayum portrait of an elderly lady features sharp contours for the brow, cheekbones and eyebrows. Created around AD 100-125, she wears a pair of drop earrings and a dark red tunic, and you can still see the remaining specks of her gold funerary wreath.

Mummy portraits, Antinoopolis, Egypt

Hans Olofsson/Flickr/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Dating to AD 100-150, this remarkable mummy portrait was discovered in Antinoopolis, an ancient city on the east bank of the Nile founded by Roman Emperor Hadrian (AD 117-138). Ever since its discovery the woman in the painting has been referred to as ‘L'Europeenne’, which means 'The European', simply because of her pale complexion. What makes this funerary panel stand out is the sheer amount of gilding which, unusually, covers the neck and chest area as well as the head. You can see it on display at the Louvre in Paris, alongside other mummy portraits.

Mummy portraits, Fayum, Egypt

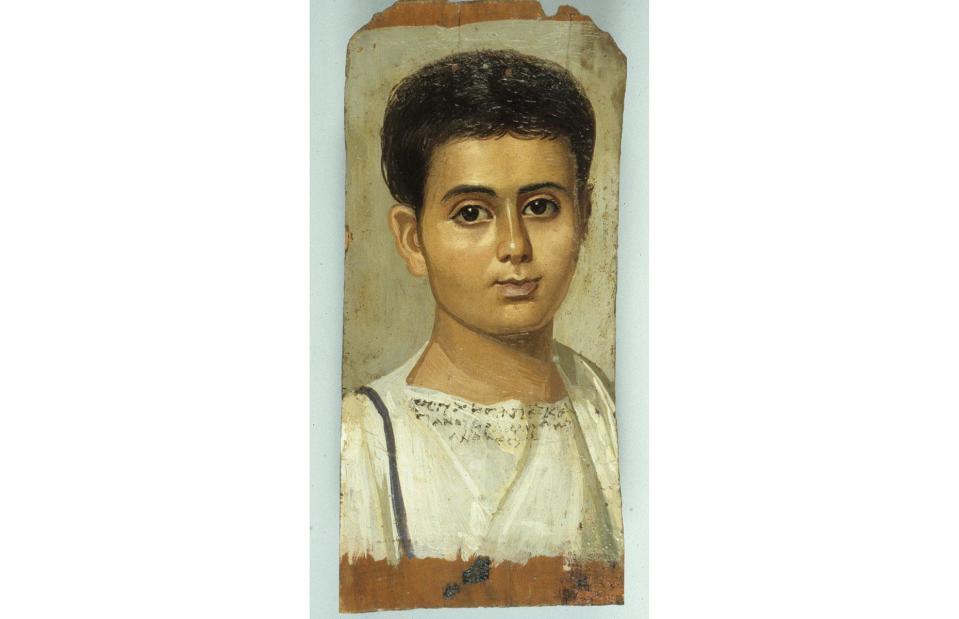

MET Museum/Public domain

Pictured in this AD 100-150 Fayum portrait is Eutyches, a young teenage boy dressed in a white Roman tunic with a purple stripe over his right shoulder. Take a closer look at the Greek inscription scrawled along the tunic's neckline. While it definitely states his name and his status as a freedman, scholars still don't know whether the part at the end of the inscription reading “I signed” is the painter's signature (which would be rare) or if it was the act of freeing Eutyches from slavery.

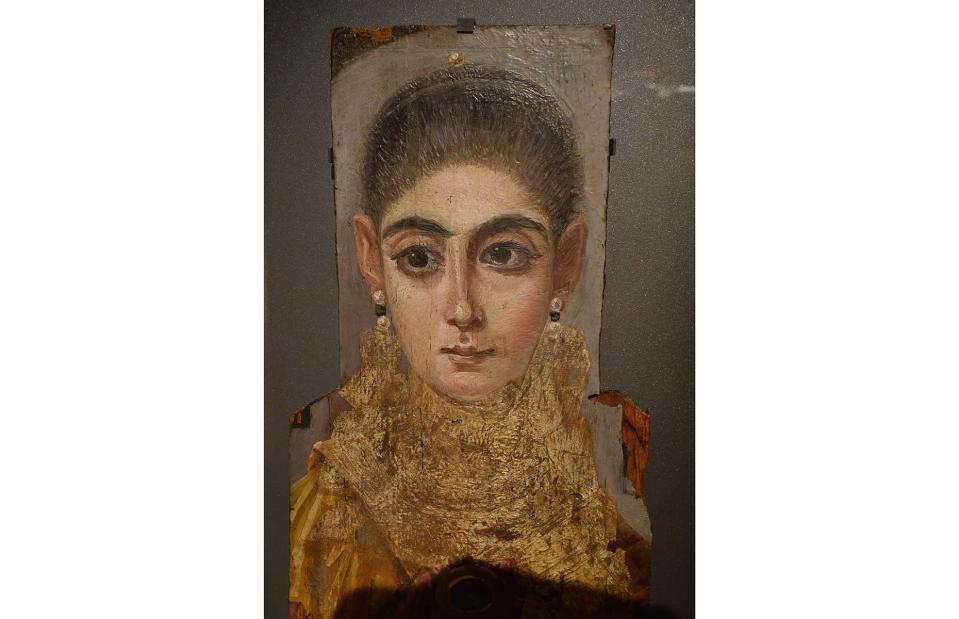

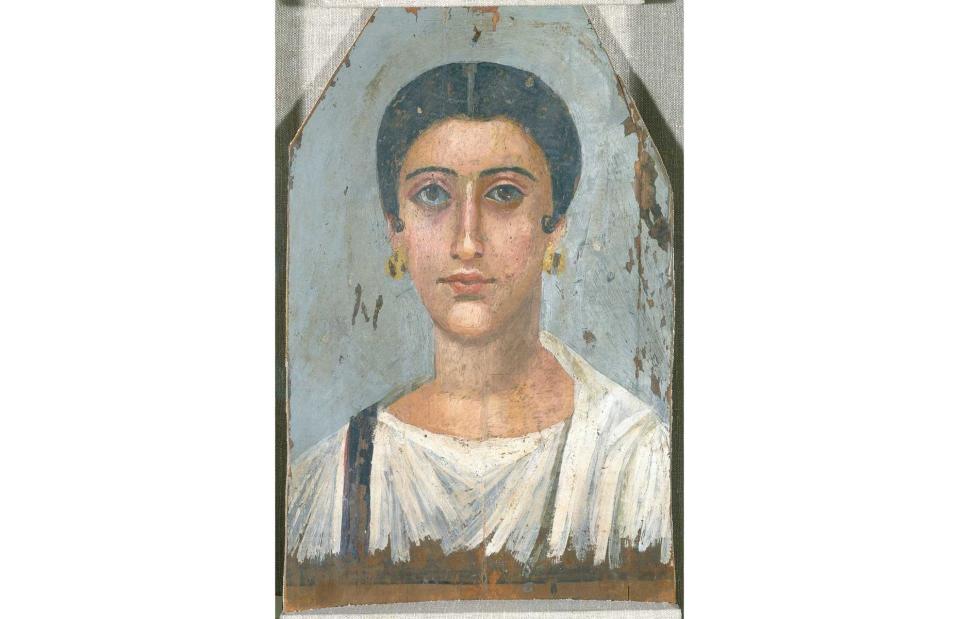

Mummy portraits, Fayum, Egypt

MET Museum/Public domain

There’s lots of small yet insightful details in this Fayum portrait. The up-do hairstyle of this young woman was typical fashion during the reign of Roman Emperor Hadrian, with the panel portrait dating to AD 120-140. The ‘Venus rings’ on her neck show her youthful beauty and she wears a lunula amulet necklace, typically worn by young girls until marriage as protection against evil. You’ll also see that the border isn’t gilded – this part of the panel would have been covered with mummy wrappings.

Mummy portraits, Fayum, Egypt

MET Museum/Public domain

Using free brushwork instead of striking contours, there’s something almost mystical about this Fayum portrait of a thin-faced man. Dated to AD 140-170, the artist has focused on his direct gaze, parted lips and strands of damp hair clinging to his brow. The gilded wreath and background would have been added once the panel was in place.

We still don't know the answers to these ancient mysteries

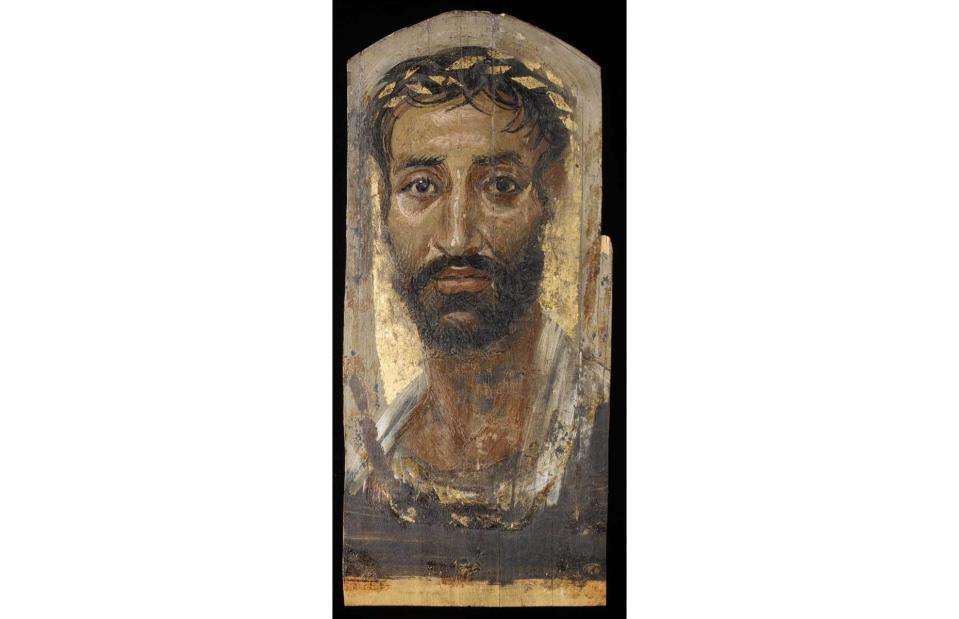

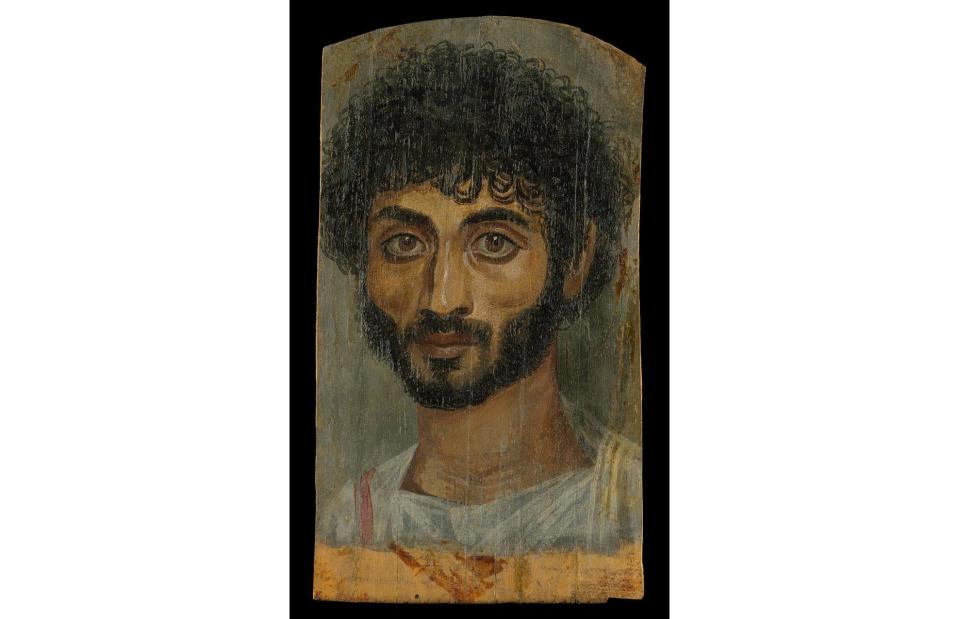

Mummy portraits, Fayum, Egypt

agis/Alamy Stock Photo

This Fayum portrait, created around AD 140-160, is thought to depict a priest of Sarapis, an Greco-Egyptian deity. The bearded man gives the viewer an intense look, perhaps wanting to make sure you don't miss his headband with its seven-pointed star. This, along with the careful arrangement of three hair locks beneath it, was a typical association with the cult of Sarapis.

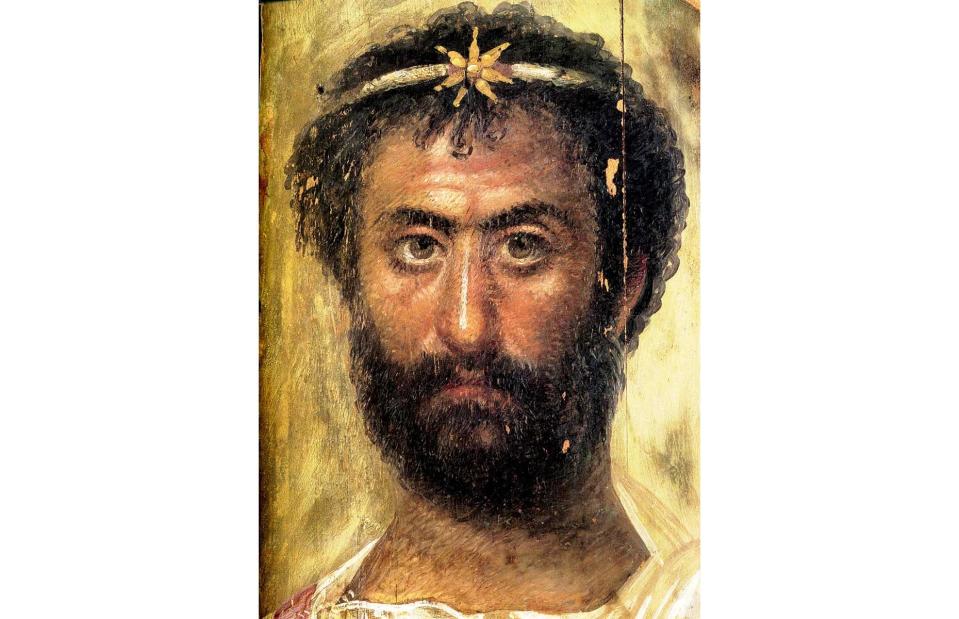

Mummy portraits, Fayum, Egypt

Brooklyn Museum/Public domain

Described by Brooklyn Museum as a portrait of a noblewoman, here we see a young woman set against a light blue-grey background. Created around AD 150, the artist painted the subject wearing Roman-style clothes, with the portrait eventually woven into a traditional Egyptian mummy. Thanks to Egypt's dry climate and being buried in darkness for so many years, this well-preserved portrait hasn't been restored, meaning you can still take in the original vivid colour and life-like depiction thousands of years later.

Mummy portraits, Fayum, Egypt

Wikipedia/Public domain

This Fayum portrait depicts a man wearing a white Roman-style garment with the typical purple band lined over one shoulder. The artist used encaustic paint, with the subject gazing at the viewer with unevenly-set eyes. Dated to the late 1st century AD, this mummy portrait is more demure than many others, with the absence of the gilded hair wreath and background. You can see it on display at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland.

These are the USA's best free museums

Mummy portraits, Fayum, Egypt

MET Museum/Public domain

You can’t help but be drawn in by this man’s enormous eyes – painting subjects with large eyes was the preferred Roman style at the time. Dated to AD 160-180, the artist used encaustic paint to depict the deceased’s once-thick beard, bushy black hair and defined cheeks.

Check out the incredible treasures the Romans left behind

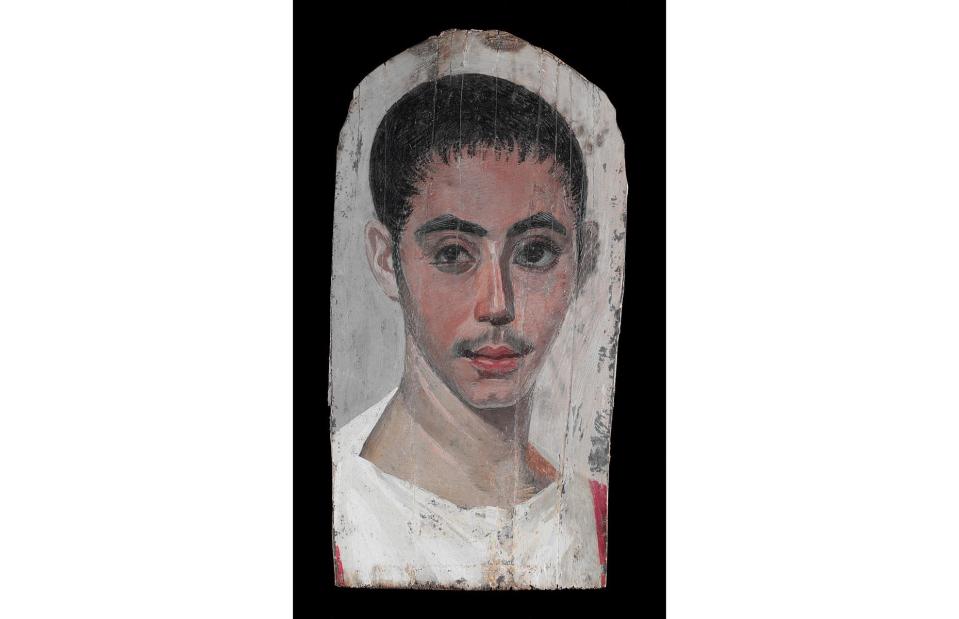

Mummy portraits, Fayum, Egypt

MET Museum/Public domain

This Fayum portrait uses a lighter colour palette to depict a young man, with faint hair on his jaw and upper lip telling us he was just approaching manhood. Created between AD 190 and 210, you’ll notice that his right eye shows something like a surgical cut. The MET Museum describes this anatomical quirk as "an abnormality that has been treated". Featuring the subject's surgical scars, this is one of the more unique mummy portraits on display.

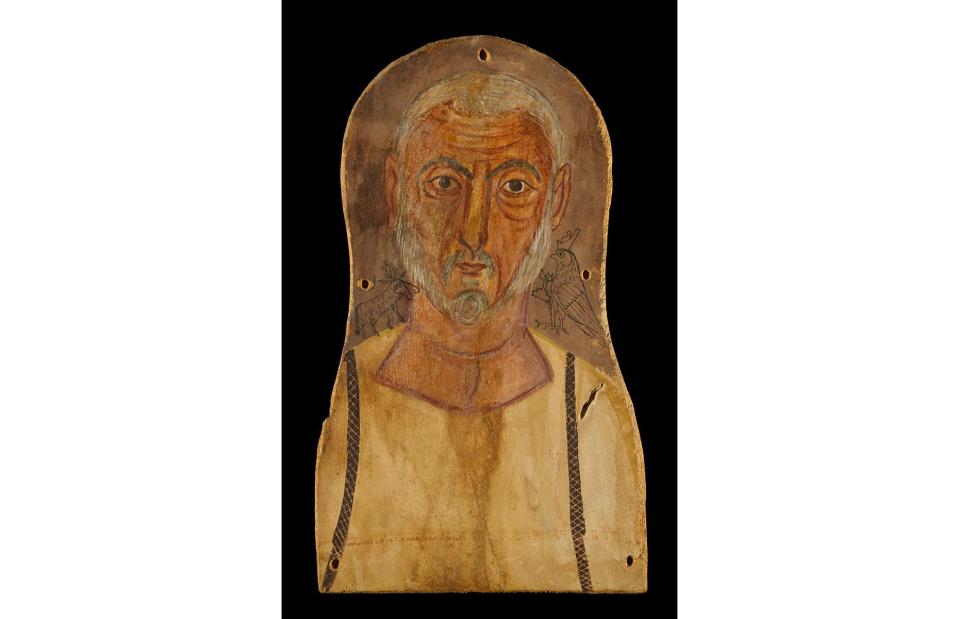

Mummy portrait, Fayum, Egypt

MET Museum/Public domain

Although this Fayum portrait was made later than others (around AD 250), it’s arguably lacking in depth and realism. Instead of using encaustic paint the artist used tempera, an older painting technique. On one of the elderly man's shoulders sits Horus, the Egyptian falcon god, and on the other a ram, which represented a deity of the underworld. You can see the five holes punched around the edge of the panel; this suggests the portrait was tied onto the mummy or coffin rather than inserted with the wrappings.

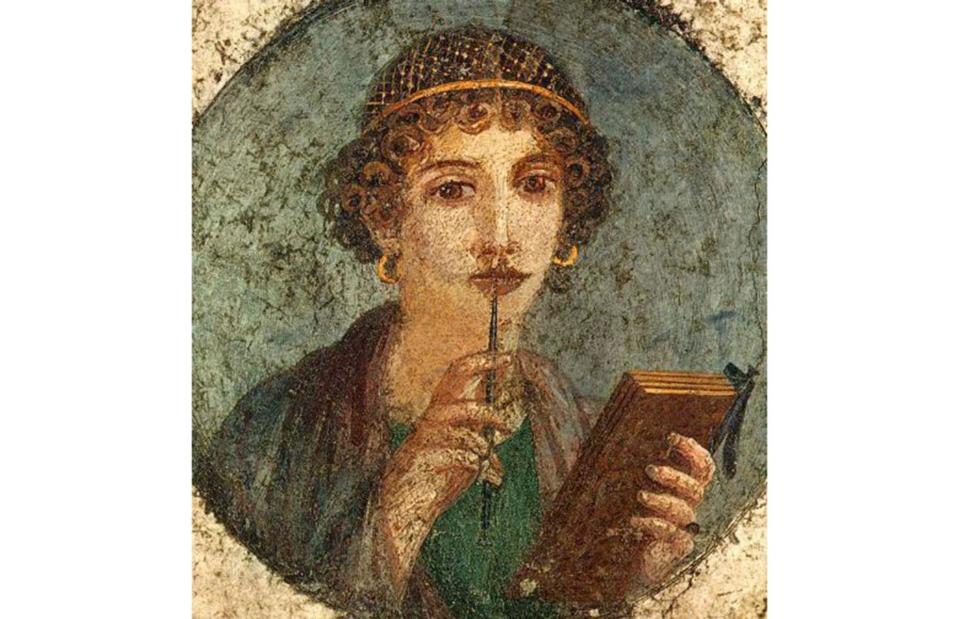

Frescoes, Pompeii, Italy

Herkulaneischer Meister/Wikipedia/Public domain

With a stylus (writing utensil) held to her lips as if in pensive thought, and a wax tablet in the other hand, many assume this is a painting of Sappho, the famous female Greek poet from the island of Lesbos. But this fresco actually depicts a high-society woman from Pompeii, the ancient Roman town that perished following the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79. She is clearly wealthy, adorned with gold-threaded hair and large, gold earrings. Dated to AD 50, the wall painting is currently housed at the National Archaeological Museum of Naples.

Frescoes, Pompeii, Italy

Olivierw/Wikimedia/Public domain

This Pompeiian fresco depicts a young man who is clearly too caught up in contemplation to look at the viewer. He wears a green laurel wreath and holds a rotulus, a type of writing document. Dating to AD 50-79, it was created during a phase of Pompeiian painting which focused on more intricate designs, similar to the 'Sappho' fresco. This fresco would have once adorned the middle area of a wall and have been set against a white background to give the impression of a framed painting.

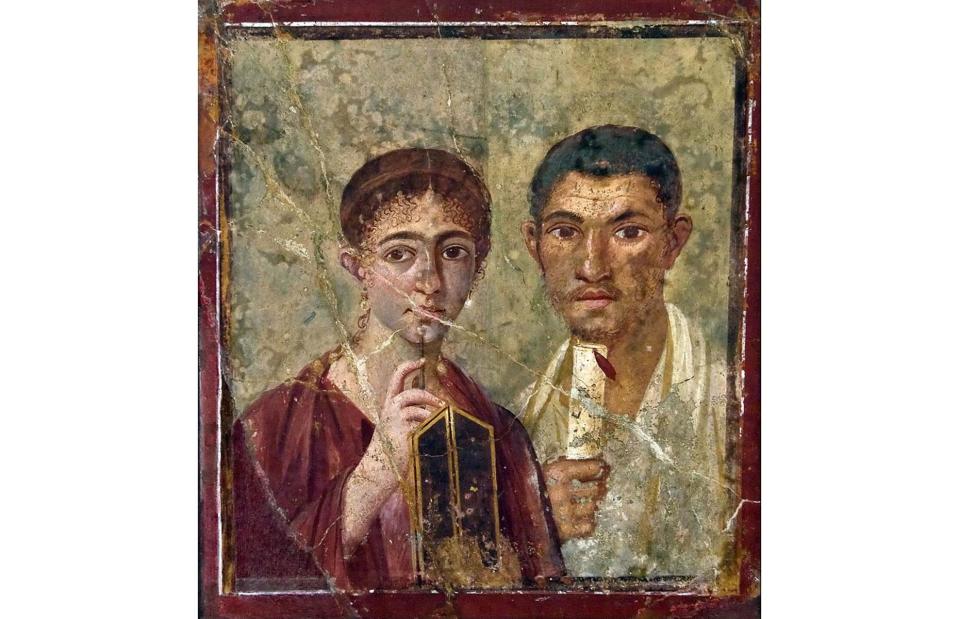

Frescoes, Pompeii, Italy

Wikipedia/Public domain

This wall painting of a husband and wife was found buried in Pompeii's rubble. The double portrait is the only one of its kind in the area and shows both Terentius Neo – a baker – and his wife as literate and cultured. Terentius holds a papyrus scroll while his wife holds a stylus and writing tablet. The fact that she holds tools of power, coupled with the fact that she stands slightly in front of her husband, suggests that they were unusually equal partners.

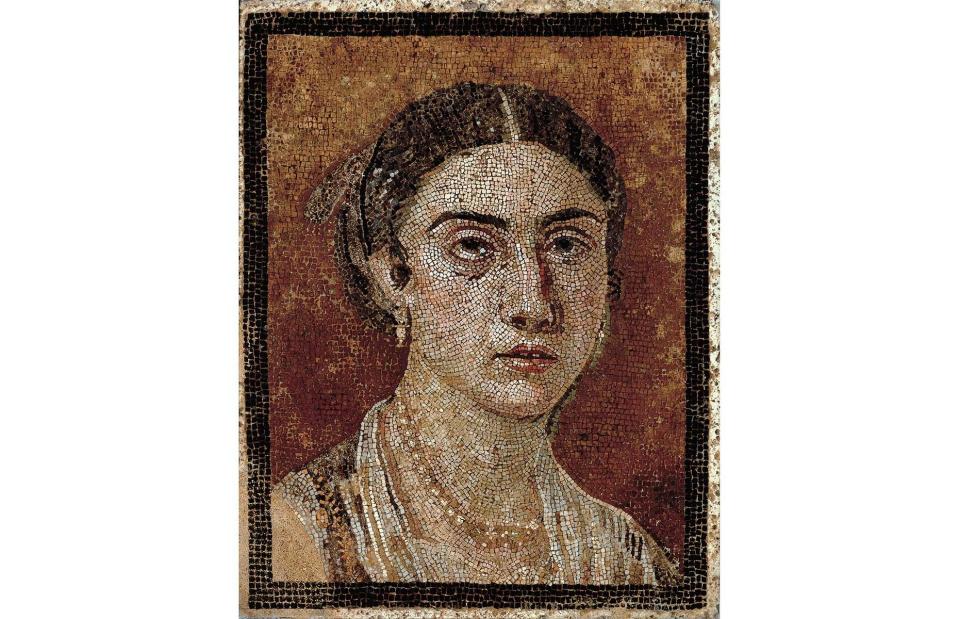

Mosaic, Pompeii, Italy

Mondadori Portfolio/Getty

It’s hard not to be wowed by this incredible mosaic of a Roman woman; see how the artist has even managed to depict the shine of her lips. The straight-faced subject wears a necklace and decorated clothing, which tells us she was part of a wealthy family, as does the remarkable detail and high-quality workmanship. Found in Pompeii and dated to some time during the 1st century AD, the mosaic was most likely displayed on the walls of a private house, and today is on display at the National Archaeological Museum of Naples.

Now discover Pompeii's secrets that are only just being uncovered