Amazon Fresh: How the supermarket of the future became the creepiest shop on the high street

There is a spectre from the west hanging over the British high street. It is luminous and empty, ubiquitous without being local, apparently financially viable despite being mildly disliked, a novelty that lost its appeal as soon as it opened. It is not the fleet of American candy stores that invaded Piccadilly Circus and Oxford Street in a period of months, a “curse” that everyone hates so much they’ve even become a touchstone of the next general election. It’s so, so much worse than that. I’m talking about the ominous, liminal space that is Amazon Fresh.

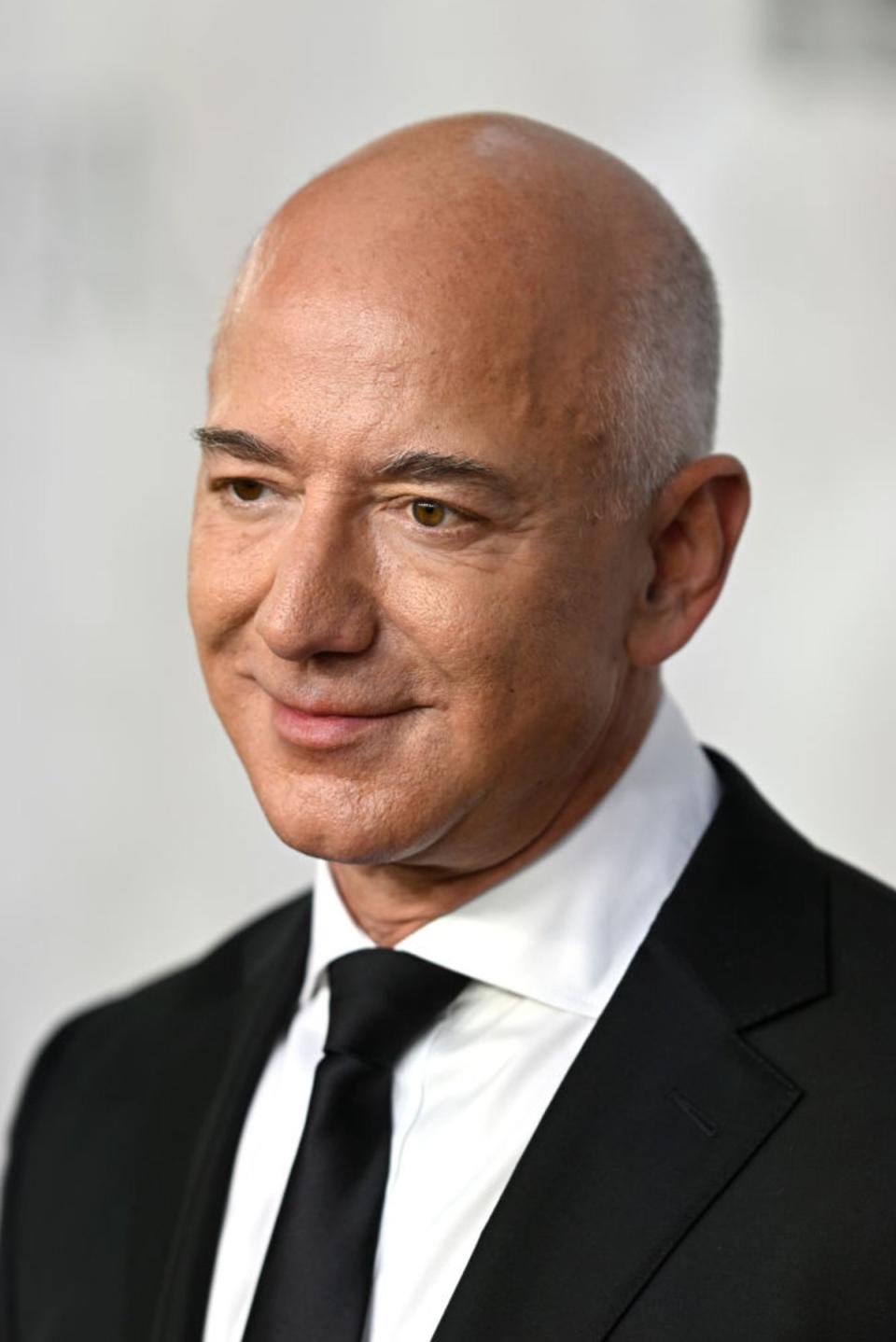

First officially launched in Chicago and LA four years ago, Amazon Fresh became Jeff Bezos’s pandemic-era foray into physical retail. Cashier-less, till-less, and vibe-less, they heralded in a new, distinctly dystopian retail experience. Here, shoppers would be watched by surveillance cameras, with the vague promise that “Just Walk Out” technology would know what they bought without their purchases being individually scanned. An early adopter of the cashless society that health food stores in Surrey hamlets now rail against, Amazon Fresh streamlined everything into our existing Amazon accounts, thereby cementing the idea that without a Prime account you are some sort of technophobic social pariah, the kind of person who covers their webcam with a sticker and declines cookies out of spite. And by tracking what we pick up and put back, the theory went, Amazon Fresh could eliminate the potential profit losses of human error, and, in the process, the need for human contact entirely. Even Foucault might have thought: bit much.

Early customers thought so too, describing it as possessing a “Big Brother” quality that not only operated from a position of inherent distrust but also mined them for their bodymetrics in the process – in 2021, just a year after its initial launch, a class-action lawsuit was filed in New York over Amazon Fresh not alerting customers that it was monitoring their body shapes and palm prints. Still, Bezos pressed ahead; by July 2022 there were 38 stores across America, and, bizarrely, at its peak, a more concentrated 19 locations across London.

This perhaps explains the ominous, panopticon-like energy of Amazon Fresh in this city; there aren’t many, but in comparison to a continent that spans 3,717,792 square miles, there are f****** loads. At its peak, there were basically half as many Amazon Fresh locations in London as there were in the third largest country on the planet. And yet, have you ever heard anyone rave about them? Or even rail against them? Does anyone actually care about these neon-green-hued Poundland-does-wasabi hubs of capitalism? Does anyone actually shop there?

To find out, I went to one in what I hoped was a suitably cursed and liminal location – that bit between Shoreditch and the Barbican. Nobody was shopping there. Obviously. Which was, actually, the only notable thing about the experience. The overall atmosphere of Amazon Fresh in real life is an eerie soullessness; the lights unforgivingly bright, the shelves unnervingly well stocked, the staff suspiciously helpful. Perhaps it’s because I’m used to the experience of being followed around a shop by a burly security guard (I think this is because I have a shifty aura, or, more likely, because I was a prolific teenage shoplifter), but the absence of these figures, and their replacement by loitering Amazon employees primed to help explain the supposedly easy – but actually tedious – experience of paying without tills or cashiers, was unnerving. “So I just tap the app?” I ask one. “Well, you can get a meal deal,” he replied. “I only really want the halloumi salad.” “Well, the halloumi salad is actually more expensive on its own, so you’d be better off getting a meal deal.” “Oh”, I say. “Right.” I struggle to tap the app because the battery on my phone is s*** and I always turn the brightness too far down to save power and then it never recognises a QR code properly. I apologise a lot, the Amazon employees apologise a lot. The halloumi salad is like, fine.

This is the overwhelming impression Amazon Fresh leaves you with: that it was all fine. Not good enough or novel enough to make you rush back, not bad enough or dystopian enough to make you curate a furious Twitter thread about the commodification of the worker, or whatever. Perhaps this is why after an initial rush of interest everyone just stopped talking about it and – if they had ever started – stopped shopping there too. While at its peak Bezos might have had 19 working locations in London, last July three of those branches closed, including the first to be opened to great fanfare, in Ealing, citing “underwhelming sales figures”. The initial flurry of attention over these new frontiers of shopping wasn’t monumental either; influencers posting “watch me walk through Amazon Fresh” videos barely broke through 100,000 views. Even Novara founder Aaron Bastani, in a video entitled “will Amazon Fresh kill the high street?” couldn’t drum up more than 23,000 people’s curiosity.

While we decided to close three Amazon Fresh stores, it doesn’t mean we won’t grow

Amazon spokesperson

This was supposed to be the future of retail, basically, and yet nobody in Britain was buying it. In the halcyon days of the pandemic, the company planned for 260 stores to flood UK high streets, though nowadays the only Fresh stores that still cling on to existence are dotted around the city and in the soulless “lunch al desko” centres of London, not in the leafy suburbs of Ealing Broadway. What’s the difference, though, between Wandsworth and East Sheen and Liverpool Street and Kensington?

Amazon was unhelpful in answering this. True to form for a trillion-dollar business that remains thriving, despite routine allegations about workers having to urinate in bottles to escape the remorseless scythe of Amazon’s performance targets, their statement was bureaucratic and vague. “Like any physical retailer, we periodically assess our portfolio of stores and make optimisation decisions along the way,” they said. “While we decided to close three Amazon Fresh stores, it doesn’t mean we won’t grow – this year, we will open new Amazon Fresh stores to better serve customers in the Greater London area.” They promised they were “committed to our investment in grocery and, as we grow, we’ll continue to learn which locations and features resonate most with customers”. None of this, obviously, means anything.

The limit of technological advancement, when it comes to something that people need to become repeat users of, like a physical store, is novelty at the expense of convenience. If they’re expensive or finickety or don’t serve a purpose that you can’t fulfil with a self-checkout in any other shop, things that are shiny and interesting won’t really take off. Nobody you actually know uses the Oculus Rift, do they? No, they don’t. Once novelty fades, you have to be drawn in by either convenience or brand loyalty. Amazon Fresh fails on both. The convenience, thanks to the fundamental weirdness of the entire shopping experience – and the fact that they only live in areas with high concentrations of shiny polyester suits and bad cocaine – means that this will never be a wholesome or convenient popping-to-the-corner-shop alternative.

And despite the ubiquity of the Bezosphere we live under, nobody actually has brand loyalty to Amazon. People use Amazon Prime in the privacy of their own homes because it’s easy, but they might feel odd about the conspicuous consumption, about the alleged labour practices that underpin being able to have whatever you want, whenever you want, delivered to your doorstep within 24 hours. We know we shouldn’t rely on Amazon, yet we do, because it’s just… easy. But there’s no pride in this. It’s the shopping equivalent of online porn, the brown box you shove in the recycling bin is the browser window you close in disgust. It ticks a box, it’s not something you’re particularly proud of, not something you would advertise.

But the UK high street, we’re constantly hearing, is nonetheless on its knees. People buy Stanley mugs and Drunk Elephant products because TikTok tells them to, and they don’t have to leave their houses to do it. A lack of investment and sky-high property costs mean that the only thing that can truly survive in the real world of retail are faceless, humanoid chains that nobody really likes but everyone just expects: this is why we have such a parasocial relationship with the Tesco meal deal, and why we all continue to shop at Pret even though we all basically hate it at this point. And even when a chain does fail, like Wilko last year, closing over 100 stores, there’s nothing to replace it. The units sit empty and depressing and nobody can be bothered to go shopping because ASOS has free returns and you can order whatever you want at your desk, while tucking into your robot-provided Amazon lunch. Luckily, somehow, there is still an often empty Amazon Fresh store, right by the office!

The saddest thing about Fresh’s continued presence is that despite the fact nobody wants it there, it will remain there until Bezos decides otherwise. It’s a truism to say “Amazon is too big to fail”, and yet… Amazon is too big to fail. So the Ealing location closed. So the one in Shoreditch might eventually follow in three years. Bezos will just move on to another new, pointless thing, whatever he wants it to be, finding new ways to make our landscape more barren and dystopian in the process with whatever colony he decides to build next. When I checked my email I realised I also got overcharged for the halloumi salad, which is annoying.