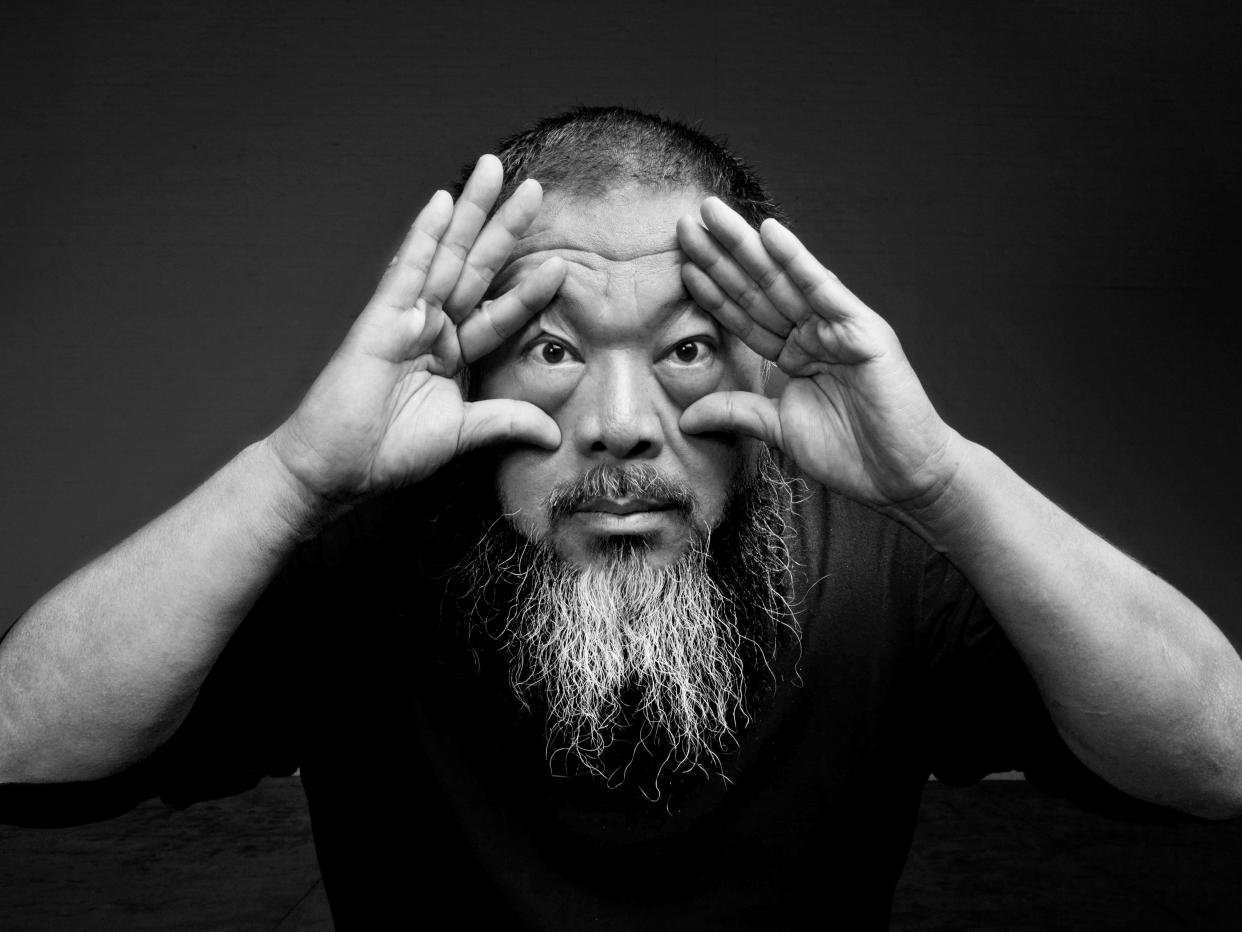

Ai Weiwei: ‘Lego is no different from Rembrandt or Van Gogh’s paint’

Ai Weiwei: ‘I thought social media could be a fertile ground for freedom of speech. It’s not true’

(Press)On 3 April 2011, Ai Weiwei was going through customs at Beijing Capital International Airport when he was stopped by plain-clothes members of the secret police. They told the dissident artist that they just wanted to talk, but instead they took him outside to a van, put a black hood over his head, and drove him in darkness for two hours to an undisclosed location.

When Ai realised he was being held in a detention centre, he had no idea how long his stay might last. “They told me I would be sentenced to over 10 years,” says the man who six months earlier had filled Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall with 100 million hand-painted porcelain sunflower seeds – seemingly identical, but each totally unique. He remembers his interrogators emphasising the cruelty of their threat. “At that time, my son was less than two and they said that when I was released he would be 13. The secret police told me very clearly: ‘Your son will never recognise you as his father.’ That touched me.”

This was just the latest in a long series of harassments that Ai suffered after he angered the government by collecting and publicising the names of 5,219 children who had died when their shoddily built schools collapsed in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. He is a vocal critic of the Chinese authorities, and there have been brutal consequences. In 2009, he was punched so hard in the head by a secret policeman that he suffered a brain haemorrhage.

In the end, Ai spent 81 long days and nights in a padded cell measuring 12 feet by 24 feet, a size he estimated by counting the floor tiles. If the intention was to crush the rebellious spirit that has defined his defiant 35-year art career, it failed. Ai has the build of a boxer and the mentality of a fighter. Rather than crumbling as the state flexed its power, he found purpose in reflecting on his relationship with his young son and with his own father, Ai Qing, a celebrated poet who was denounced during Chairman Mao’s purges in 1957.

“I said to myself: ‘I have to write down what happened to me, and to my father, so that I can leave it to my son,’” he says. “It was only in detention that I realised there were so many things about my father I didn’t know. This is often the way with parents and children – you think you know everything, but you don’t. You never really investigate or ask questions directly, so that became a sorrow in my life because it’s something I can never catch up on.”

He didn’t want his own son to end up carrying the same regret. “That’s why I started to write my memoir – to tell my son honestly what really happened,” he says. “I feel I’ve achieved that. It has taken 10 years. I’ve worked very hard. It’s the longest project I ever did, but I really wanted to make it right. Not only make it good, but make it right.”

Later this year Ai, 63, will publish that long-gestating memoir, 1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows, offering insights into his artistic practice and activism through the framework of the last century of Chinese history. He is speaking on a video call from his new home in Portugal, a villa on a country estate east of Lisbon, where he lives with his three cats, Shadow, Half and Yellow. He also keeps exotic birds, which I can hear tweeting their musical accompaniment as we talk.

Ai left China as a political refugee when the authorities returned his passport in 2015, and he set up a new studio in a former brewery in Berlin. He lived for a while in Cambridge, where his son is at King’s College School gaining what Ai calls “a proper English education”, but he soon realised life there wasn’t to his taste. “Cambridge is a campus, and campuses are places I’m allergic to,” he says. “I’m not interested in anything that happens in this kind of collegiate atmosphere, so I had to find a place to spend the rest of my life! By coincidence I came to Portugal. I’m a person who makes quick decisions. I like the sunshine. I like the softness of the culture. The people are friendly, the food is good and it’s a nice environment, so I decided to become a resident.” He shrugs contentedly. “I like it here!”

He laughs off my suggestion that his decision to leave Britain might have had anything to do with Boris Johnson’s mishandling of the coronavirus pandemic. “I don’t pay much attention to those political figures,” he says. “Somehow I realised that there’s only one political figure, and that’s the one in power. If they’re not in power, they disappear. When they’re in power, somehow they all have the same kind of character. It’s very hard to find someone in power who is interesting, humorous, intelligent, ambitious and can be convincing – so no, I didn’t pay much attention to him.”

Ai’s idyllic new life in the Portuguese countryside is a far cry from the conditions he grew up in. In 1958, when he was one, his family were sent to live on a labour camp in Heilongjiang. After that they were exiled to remote Xinjiang for the next 16 years. Ai spent his early teenage years in the Gobi desert, watching his intellectual father forced to work in labour gangs clearing sewage ditches. The experience couldn’t help but politicise him, and it still burns in him. As we talk, he raises his phone to the screen to show me the picture he has chosen to set as his background: a black-and-white photograph of where his family were made to live. “You see that black area? Between 10 and 15, I lived in a hole,” he explains. “As a punishment we were made to live underground. Before we lived there we had to dig it. The walls would always have dust coming down, so we had to look for newspapers to glue to the walls.”

In 1976, Ai’s family were finally allowed to return to Beijing. Five years later, at the age of 23, he left China for the first time and moved to New York, where he studied art at Parsons School of Design. He quickly fell in love with the energy of the East Village, and even found a surrogate father figure in the beat poet Allen Ginsberg. “I hadn’t seen my father for a long time, because I never travelled back when I was in the United States,” he remembers. “Allen had actually met my father when he travelled to China. When he came back he gave a poetry reading at St Mark’s Church, so that’s how I met him. We were very close. I think he reflects the writer’s tradition, which my father is also a part of, but at the same time my father never had this kind of freedom.”

Ai was a talented but truculent student, particularly because he’d quickly developed a dislike for more traditional forms of art. “I abandoned painting when I was in New York,” he remembers. “I couldn’t get used to framing canvas on stretchers, which is very typical in oil painting, and I don’t like the smell of it. I can paint very well, but I don’t want to do it.”

His early works were primarily installations or sculptural objects, often showcasing his agitational sense of humour. Safe Sex, a 1986 piece from his debut solo exhibition, created in response to the first wave of the Aids crisis, is a fireman’s overcoat with a condom protruding from it in the anatomically apt position. Later, as his fame grew and he was invited to put on museum shows, Ai realised that without paintings he would often be left with bare walls.

“I thought: ‘What a waste!’, so I decided I should think of something to go on them,” he says. His thoughts returned to the newspapers his family had once glued to the sides of their home, and he struck upon the idea of a medium that has since become a key part of his exhibitions: wallpaper. His recent designs include Odyssey, which depicts the global refugee crisis in the style of a Greco-Roman frieze. “Wallpapers naturally have a very long tradition of covering walls, usually just to decorate, but wallpaper also reflects status, taste and culture,” he points out. “I like creating wallpaper, because it changes the environment immediately.”

In April 1993, Ai received word that his father was ill, and quickly returned to Beijing (his father died three years later, in 1996). Ai continued to work but was unable to get official permission to stage an exhibition, so in 1994 he published – along with Xu Bing and Zeng Xiaojun, two artists he knew in New York – the subversive Black Cover Book, a collection of art and writing that would never have been approved by the Chinese authorities. They sold copies illicitly in front of Beijing galleries, like drug dealers.

The books were Ai’s attempt to stimulate an independent art scene in China, and his rebellious reputation was growing rapidly. He courted further controversy with his 1995 work Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, a photographic triptych which depicts the artist destroying a 2000-year-old ceremonial vase in mocking reference to Mao’s insistence that “The only way of building a new world is by destroying the old one.” Notably, in 2003, he collaborated with Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron on a design for the new Beijing National Stadium, now widely known as the Bird’s Nest, which was constructed to host the 2008 Olympic Games. However, before it even opened Ai had disowned his work, calling the games a “fake smile” intended to conceal China’s many problems.

When I ask whether he at least takes some satisfaction in having created a work of art so monumental that even the Chinese authorities can’t censor it, he says it’s not that simple. “I think it’s naive for artists or architects to have this kind of fantasy about our work,” he says. “Eventually, those works are still under the control of the powerful. It could be a state, it could be a church, or it could be a big corporation. So, yes, this is great work, but it’s not functioning in a way that we can celebrate.”

Even now, after six years in exile, Ai finds he cannot escape China’s tentacles of influence. His recent documentary Coronation, filmed in secret by his friends and associates in Wuhan, is a chilling portrait of China’s militarised response to the pandemic that he says has been passed over by festivals and distributors who fear antagonising the Chinese authorities.

“The selectors from the film festivals in Venice, New York and Hong Kong, and online distributors like Amazon and Netflix, they all told me they love the film and they couldn’t believe a film like this could be made,” he says. “Yet they all rejected it. Why would they make this decision? Because they have to calculate, if they accept this film, what do they lose? China has become the number one film market, surpassing the US. Hollywood changes their lines, even their stories, for this market. We are living in a commercial world, totally. We can’t imagine that human rights, freedom of speech, can still hold value for humanity. They just become bargaining chips. Those are the facts and I have to accept them, and I’m happy about it only because that means my work is very relevant.”

He says this with a wry smile, but it’s true that China’s many attempts to silence Ai have only served to amplify his voice. He released Coronation himself online, while galleries around the world still clamour to display his work. His exhibition Trace, which opens today at Los Angeles’ Skirball Cultural Centre, features his wallpaper installation The Animal That Looks Like a Llama but Is Really an Alpaca. Its pattern is made up from the iconography of surveillance – handcuffs and CCTV cameras – along with tiny alpacas, a mascot of freedom of expression in Chinese internet culture.

The work also features repeated images of Twitter’s bird logo. Ai has long championed social media for its ability to give voice to the voiceless, but when asked how he weighs that against the waves of misinformation that now spread across it, not to mention the armies of bots controlled by governments such as China and Russia, he reveals his enthusiasm for the platform has dimmed.

“It’s likely almost impossible to clean it up,” he says, sadly. “Social media is like a print of reality. Reality is so messy, and social media is a mirror image of it. At the very beginning I gave it high praise. I thought social media could be a fertile ground for freedom of speech, and could help us to better protect civil rights. It’s not true, because even social media is owned by big companies. Clearly, they will allow what they like and not allow what they don’t like.”

The centrepiece of Trace is a series of monumental portraits of prisoners of conscience from around the world, rendered in another idiosyncratic medium that Ai has made his own: Lego bricks. His eyes light up when he talks about making art this way. “Lego, it’s a second language,” he rhapsodises. “It’s not painting and it’s not sculpture and it’s not installation. It looks like two dimensions but it’s actually three.”

He conceived the idea while under house arrest in China in 2014, seeking a way to create work that could be reproduced by collaborators overseas. “Lego gave me the opportunity to give a clear design that could be followed by the constructor,” he says. “It’s digitally precise, so it’s no different from a so-called ‘original’. Lego destroys this idea of an ‘original’, which I like. I always like artworks that don’t have to be done by artists. It’s only the idea that comes from the artist. The easier to make, the better the work is. I think Lego is no different from Rembrandt’s paint or Van Gogh’s paint. If they were alive today, they would love to play Legos.”

Even now, after a lifetime spent battling state oppression, Ai remains playful, an eternal optimist in a world that keeps trying to make him a pessimist. I ask him where he finds hope, and a smile plays across his lips. “It’s easy,” he says. “I don’t think it’s a bad world – it’s just a corrupt world. It’s a spiritually totally corrupt world, and life is short. You can be corrupt until you die, it’s no problem.”

I get the sense the arch provocateur is once again being provocative. Can he imagine a world without such corruption? “A human world? I cannot think that way, but there are always fighters, defenders and soldiers,” says Ai, always ready for his next battle. “If you’re a fighter, you should not be afraid of having a scar on your face, or of getting hurt or crippled – because, you know, that’s the nature of the fighting.”

‘Ai Weiwei: Trace’ is at the Skirball Cultural Centre in Los Angeles from 15 May-1 August. The artist’s memoir, ‘1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows’, is set to be published on 2 November

Read More

Flying Lotus: ‘I’ve been an anime fan forever, but I never thought I’d be part of this world’

From David Hockney to Paula Rego – the art exhibitions to see when art galleries and museums reopen

Sons of Kemet: ‘It’s hard to heal when you’re still receiving aggression’