Ai Weiwei and the Echoes Inside

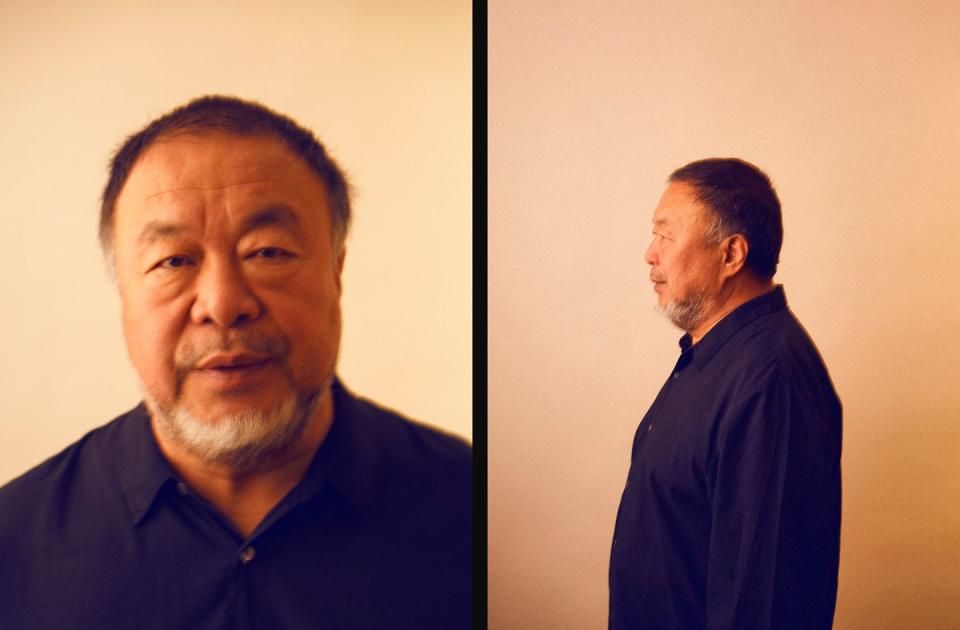

Sitting across from me in a corner table of a London hotel restaurant, with his grey-flecked beard and somewhat crumpled navy shirt, Ai Weiwei’s appearance is both unassuming and iconic. His is a face instantly recognisable from the posters and artworks that appeared in streets and museums around the world when, in 2011, the 64-year-old artist and outspoken critic of the Chinese government was detained at Beijing airport for unspecified “economic crimes”. He was kept in solitary confinement in a tiny cell for 81 days before being released without charge.

Ai recounts, in jaw-dropping detail, the episode for which he is most famous in his new memoir, 1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows. The idea for the book came to him when he was taken into police custody; in isolation, he found himself reflecting on the experiences of his own father, the renowned poet Ai Qing, who, during the Cultural Revolution that began in 1966, was branded an “anti-Rightist” and banished to a re-education camp in Xinjiang known as Little Siberia. There, he was made to clean the latrines. For five years, between the ages of 10 and 15, Ai Weiwei lived in Xinjiang with his father in a rudimentary shelter dug out of the earth. “I resolved to write an account of his life and mine, and to share this memoir with my son, Ai Lao, who at the time of my arrest had just turned two,” he writes in his book’s acknowledgements.

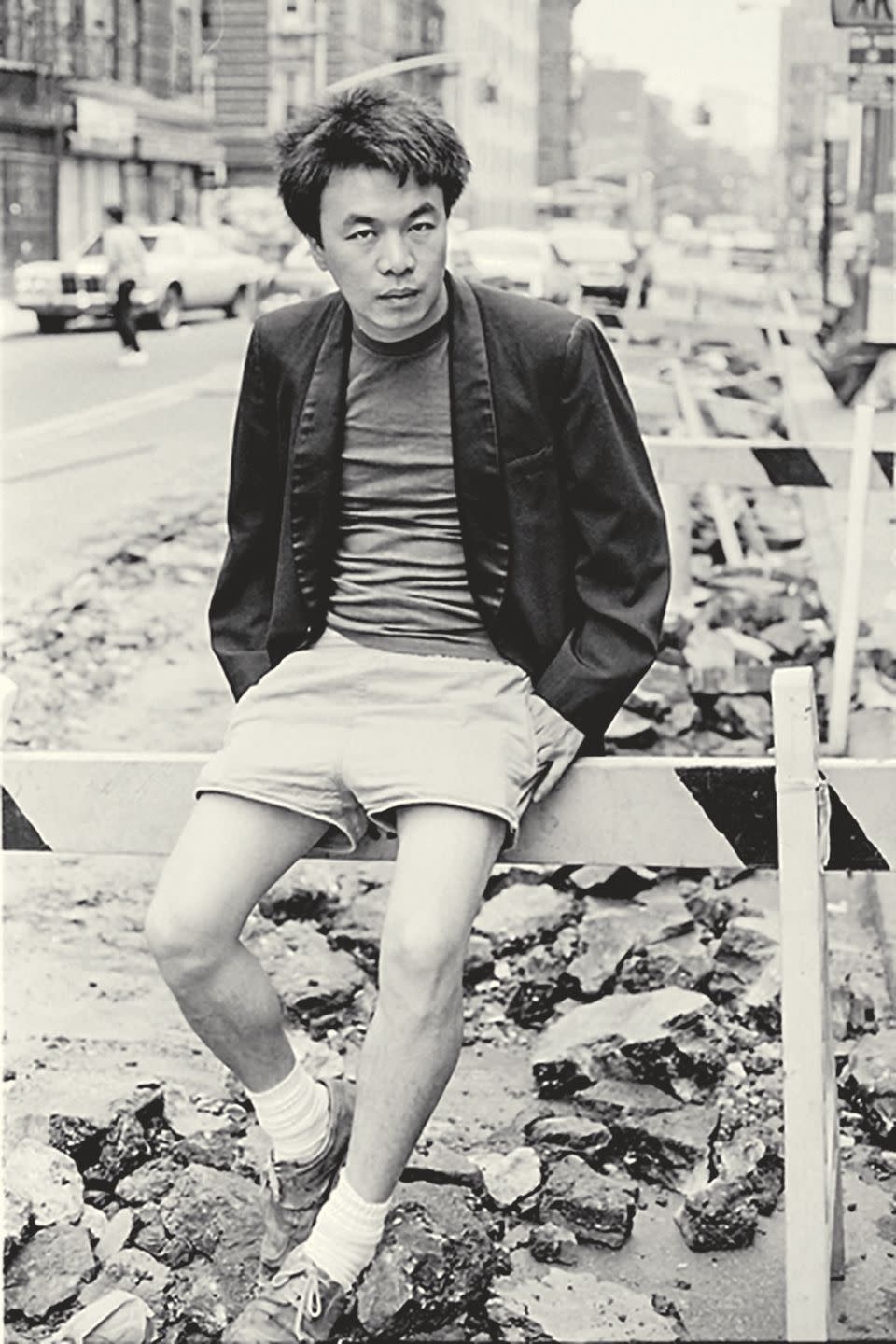

As a student in the 1980s, Ai would travel to New York, and gradually build up his artistic practice and international reputation, later cemented by landmark projects such as his design, with the Swiss architecture firm Herzog and de Meuron, for the iconic “Bird’s Nest Stadium” at the 2008 Beijing Olympics, and his 2010-11 installation, “Sunflower Seeds” in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall. Since leaving China – his passport was not returned to him until 2015 – he has based himself in Berlin, Cambridge and, most recently, Portugal (“Three hundred days of sunshine,” as he reasonably points out).

Even after his confinement, Ai has continued to be a vocal critic of the Chinese government, and decry social injustices across the world, both through his words and his work. The day before we meet, he had joined a protest outside the Royal Courts of Justice in London against the extradition of Wikileaks founder Julian Assange. Later that evening, a new film piece reflecting on some of his most important past work would illuminate the electronic billboards above Piccadilly Circus. It is evident that, despite having already lived a life full of astonishing events and extremes, the 64-year-old Ai is far from done.

Why did 1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows take you 10 years to write?

You want to make it as truthful as possible, so every detail of the political struggle requires a lot of study. It may come out as one sentence, but I have to understand what I am saying, you know? I cannot automatically put what has been given by historians. Especially in China. Many facts cannot be revealed and you cannot trust anything. I wrote for two hours daily, and this is the fifth version. They reduced it from 800,000 words. It’s really a heavy project for me.

The book is about your family’s history, but it also about the last 100 years of China’s. Would it have been possible to write about one without the other?

Well is there a way to separate a fish from water? Maybe, but not in my case. I survived that stream, but I also cannot live without it. It’s impossible.

Living in exile with your father, what did you understand about what was happening politically?

As I child I did not understand that much, but still now I will not say I understand so much about China. It’s like a group of blind men trying to figure out what an elephant is like. One would touch his tail and say, “Oh, an elephant is like a sweep!” another touches the trunk and says, “An elephant is like this…” They touch an area which relates to a larger picture, but they don’t have a clear scope. My knowledge is simply not good enough to have a concrete idea, though I can imagine.

You describe constructing a lamp and a stove during that period with your father. Do you think that is where your interest in making began?

I think it’s not about interest in making, but awareness that you can change a matter by acting on it. Without a lamp you would be in total darkness, but with a lamp you would have light, which is very low, but still it’s better than darkness. With putting up a stove, you have warm water, otherwise you have frozen water. It gives you wisdom about what is necessary and what is not necessary. I think in modern society, we don’t know that.

You write that your parents would often say that your birth marked the start of their misfortunes. Why did they say that?

When I was born [in 1957], that was the year that the word “anti-Rightist” came along. My father was under heavy political criticism, so if he opened the newspaper the headline would be him. My mum was running in the street before the postman came to get the paper and tear out that page; in China, the newspaper is more important than a trial. Of course it was a metaphor, and it wasn’t fair to offer that conclusion, but what is fair? What happened to them was not fair. When I was born their life completely changed. But they are not blaming me. That’s the facts.

Later, when you left Beijing for New York, did you really tell your mother that you were going to be “the second Picasso”?

I did say that, and I was very confident. I never knew I would be better than Picasso. Haha! And my mum was very, very disappointed when I came back empty-handed. No money, no American passport. I don’t even have a university diploma because I never recognised that it’s important until very late. Still, when I have to write a resumé, I think, “God, I don’t have anything to write!”

What was it like arriving to New York in the 1980s?

I liked to be alone, I liked to act on my own. I didn’t care about success – I really don’t care about success. Just leave me alone. And in that sense I enjoyed being in New York, as the most lonely and unromantic city, a dangerous and harsh society. I like the harshness. It’s so cold. You realise you’re just like a wild wolf walking on every street.

You got some encouraging words from Allen Ginsberg while you were there – can he take some credit for this book happening?

Yeah he cared about talking about my past. I had a little chat and he said, “You really should write down what you have.” I thought, “Write down what I have? I think that’s the most ridiculous suggestion. Who cares anyway? I don’t even care myself.” He was a kind person, and he was always an inspiration, but I followed the literature tradition long before he told me that. I respect my father and a whole generation of poets and writers. Putting ink on paper is such an admirable act of the human being. Only humans do that. To record your thoughts with these marks.

The book includes images of some of your earlier works from when you went back to China, which have a certain irreverence, such as a photograph from 1995 of you giving the finger to Tiananmen Square. How do you feel about those works now?

You know, today when I look at it, is it too casual? Too ridiculous? But my life the moment when I did it was casual and ridiculous, so I was being honest about my own state of mind.

You designed the Bird’s Nest stadium for the 2008 Beijing Olympics, but in the memoir you refer to those games as a “grotesque jamboree”. Do you regret participating?

No I don’t regret it. I designed the stadium because I love architecture, and it was a wonderful design. What I don’t like is the Communist Party using that as state propaganda for nationalism, which is why I refused to go to the opening. I’m very clear about that.

Did that mark a key turning point in your relationship with the state?

I think the true turning point is 2008 before the Olympics opened, when there was an earthquake in Sichuan. In that earthquake, 80,000 people disappeared, and among them were 5,000 students. I kept asking, “How does a school built by the state collapse, but the building next to it not collapse?” We started an investigation, as a kind of civil act. We said, “Who is dead, and what are their names?” They said, “It’s a national secret.” We said, “It’s not a national secret, it is a public event, you’re responsible to tell us the truth.” The confrontation became so direct and they realised I had so much power on the internet that they shut down my blog. They said, “This guy’s uncontrollable.”

When did you realise they were watching you more closely?

The surveillance started in 2009. I saw people following me everywhere. If I was walking my son in the park, pushing the pushchair, there were people behind bushes taking photos. Cars followed us everywhere, there were people sitting by my front door to record whoever comes. It was normal. I told them, “You know I don’t have any secrets? You’re the ones that have secrets.”

When they arrested you at Beijing airport, the police put a bag over your head and drove you to a secret location. What did you think was going to happen?

When I was taken away, I think I knew it was deadly serious because why they have to do it in that way? At home they could have said, “Weiwei, come with us.” Why did they have to kidnap me from the airport and take me to some unknown place? I asked them, “Can I call my mum to say I’m safe?” Or “Can I have a lawyer?” They said no. I was prepared in a way, because I knew my actions would have consequences. If they’d said, “You will be sentenced for 13 years,” I would not have been surprised. Because I did more than anybody in that society, openly, against what they do. Nobody did that.

The descriptions of the routines imposed on you when you were in confinement are so vivid, each activity scheduled down to the minute.

They were so precise. The guards would have to look at their watches and to the second they would tell me what to do. It was so sharp. If I took a shower a little bit faster, then I would have to stand next to the bed, nude, my whole body streaming. They’d look at me, standing there, then they’d say, “Go.” I would get into the bed, two soldiers standing right in front of my bed, and after that second the surveillance monitors would not see any movement in the room.

You draw a few parallels in the book about things that have happened in China and things in the West, such as the “big character posters” used to denounce your father, which you compare to Facebook. Is that to make it clear such things happen everywhere?

You’re right. The book ends in 2015, when I was released. I have a lot more to say about democratic society, “freedom” society, or international politics. There’ll be another book.

The title comes from a poem by your father about the futility of human endeavour. Why did you choose that?

We have to put ourselves on a larger scale. We’re so sophisticated, such intelligent creatures, but at the same time we’re so suicidal. Daily, species are disappearing because humans are present. And we create situations we can never even cope with, like climate change. I don’t think there’s a simple answer to the refugee situation, or climate change, or China-Western relations. But at the same time, my father writes that all of human joy and sorrow won’t even leave one trace. We have to face daily matters, but also have perspective about what we’re doing.

Did writing the book help you feel more of a connection him?

We had a casual, friendly relationship. Not like father and son. I remember his integrity as a writer, I’d read a few really famous poems that everybody knew at school, but to tell the truth I never completed reading his writings. I never thought about his life until writing this book. But it is so colourful, so dramatic. Since he was born, he went through so much. It’s just one episode after another. Like dropping into a heavy stream, it pushes you. I realised I’m part of that. Because he’s my father it brings all those consequences to me.

You include some poetry by your son, who is now 12. Do you think he has taken after you or your father?

No I don’t think so, I never tried to influence him. The day before yesterday we got the book for the first time. The publisher said, what do you think? So many people worked on it, and also I worked on it for 10 years. So I did a little act with my son. We burned it.

Why?

Why not?

Did your son like the book?

He also liked the fire. Today he is visiting this stupid museum about wax.

Madame Tussaud’s?!

I said, “Why do you go to this kind of thing?” I was thinking it must be horrible, but I can’t stop him. He told his mum he wants to be a designer. He said his grandfather is a poet, his father is an artist, if he is a designer, “My son might be a street graphic artist.” So he’s a very funny guy. It’s a different world.

1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows by Ai Weiwei (The Bodley Head) is out on 2 November

You Might Also Like