The 1920s bohemians who put the sex into Sussex

Flint and brick, hill and meadow, river and coast. The South Downs make for a magical landscape. Heading south from London they are the last rolling swell of high grassland before you get to the chalk cliffs, marshes, beaches and winding estuaries of the coast. It’s a gentle, sometimes mysterious world of dead-end lanes, wildflower meadows, sudden unexpected views, quiet villages and isolated farmhouses. The perfect place for a rural getaway.

Yet, while seaside holidays have long been part of our national life – with the East Sussex resort of Brighton in the forefront in the early 19th century – the countryside has not. The idea of stopping before you get to the coast, of stepping off a train at a sleepy rural station and escaping to a rose-garlanded cottage, is a rather more recent trend. And it owes much of its appeal to the vision of a disparate group of artists, writers and bohemians – and their often exotic lifestyles – who took over the villages of the Sussex Downs from the 1900s onwards.

First on the scene was the community of designers and craftsmen that began to settle in Ditchling in 1907. The less said about one of the founders – the talented but abusive Eric Gill – the better. But he left in 1923 and the wider community that had emerged from the Arts and Crafts movement a generation earlier went on to flourish for several decades afterwards. There is still a cluster of studios and practitioners in the village, which has nurtured more than its fair share of creative talent.

The actor Sir Donald Sinden grew up here in the 1920s and 30s: his father was the local chemist and a great friend of one of the leading artists of the village, Sir Frank William Brangwyn. And after moving to Ditchling in the early 1960s, Dame Vera Lynn – a keen amateur painter – spent most of the rest of her life here.

Meanwhile, further east was the haunt of Eric Ravilious, one of the most sensitive observers of the Sussex countryside and whose reputation continues to grow. He studied at Eastbourne School of Art in the early 1920s, and was later taught by the surrealist painter and war artist Paul Nash who also lived in East Sussex for a time, in a house that overlooked the marshes at Rye. Ravilious’s evocative woodcuts and paintings perhaps capture the mysterious beauty of the Downs better than any.

In the far west, meanwhile, poet Edward James, an important patron of surrealist art, was a generous host at his estate at West Dean, where he installed Salvador Dali’s sofa – modelled on Mae West’s lips – and his lobster telephone.

But it was the Bloomsbury group that left the most indelible impression, partly because of the extraordinary range of talented people who came to live or stay at Charleston – a modest but idyllically-situated farmhouse near Lewes – and partly because of the extraordinarily complex warp and weft of their love lives.

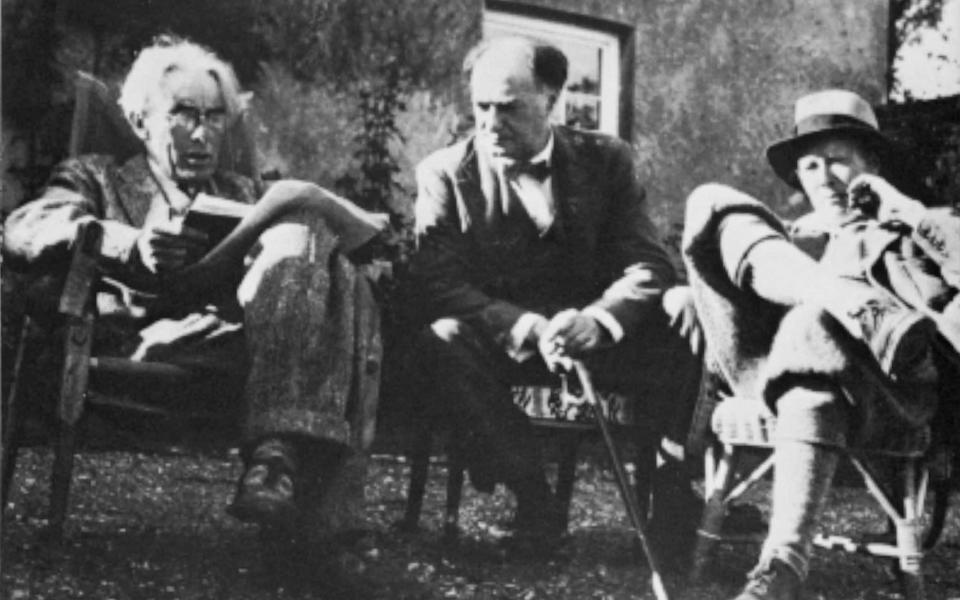

In 1916, author Virginia Woolf, who had been coming to Sussex since 1910, recommended Charleston as a rural base for her artist sister, Vanessa Bell, and fellow artist Duncan Grant, who had to leave London to find farm work as a condition of his exemption from military service. Vanessa was married to the art historian Clive Bell, but Bell only came to Charleston later and in 1918 she had a child, Angelica, by Grant. Meanwhile, Grant’s male lovers included his cousin, the historian Lytton Strachey, and the economist John Maynard Keynes, who were both regular visitors to East Sussex.

Clive Bell also had serial affairs, and soon after his marriage to Vanessa had fallen in love with her sister Virginia – who bought a cottage in nearby Rodmell in 1919. Virginia was married to the publisher Leonard Woolf, but had multiple lovers of her own, notably Vita Sackville West, the garden designer who lived about an hour’s drive away at Sissinghurst.

Still with me? It gets even more complex if you dig deeper (the complicated love lives of Sackville West and her husband, the writer and politician Harold Nicholson, for example, were detailed by their son Nigel Nicolson in his 1973 biography Portrait of a Marriage) but, remarkably, most of these affairs seem to have ended relatively amicably.

Perhaps there was something special about the atmosphere at Charleston. Vanessa Bell’s description certainly suggests happy times: “The house seems full of young people in very high spirits, laughing a great deal at their own jokes [...] lying about in the garden, which is simply a dithering blaze of flowers and butterflies and apples.” The suicide of Virginia Woolf in 1941 was a bleak moment, but marriages remained broadly intact and lovers remained close. Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant stayed at Charleston together until their deaths – Bell in 1961, Grant in 1978 – and are buried next to each other in the nearby churchyard at Firle.

How to visit Sussex, from art to opera

Charleston

The farmhouse decorated by Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant is one of the most atmospheric of any artists’ houses. Most of the doors, panelling, and other woodwork were playfully embellished by the artists and many of the paintings, books, furniture and memorabilia date back to the 1920s and 30s. The garden – designed by Roger Fry – is especially fine. Recently it has been enhanced by new exhibition spaces in the former barns, and a busy programme of talks and events Visits to the house are by guided tour only and leave every 10 minutes, but you’d be wise to book in advance (charleston.org.uk). The garden is free to visit during opening hours.

Monk’s House, Rodmell

This modest cottage in a backstreet in the village of Rodmell is where Virginia Woolf and her husband Leonard spent holidays from 1919 and eventually lived permanently. Guests at the home, now owned by the National Trust, included TS Eliot and EM Forster and it is only 11 miles by road from where Woolf’s sister Vanessa lived in Charleston. An evocative 1920s/1930s atmosphere is retained in both the house and garden, where her wooden writing lodge is preserved and it is a few minutes’ walk out across the nearby marshes to the spot where Woolf drowned herself in the River Ouse. Advance bookings only – opening times are very limited and tickets go on sale every Thursday for entrance for the following four weeks (nationaltrust.org.uk).

Rathfinny Wine Estate, Alfriston

If you need some refreshment while touring East Sussex, the Rathfinny vineyard, in the chalk uplands just above Alfriston and overlooking Cuckmere Haven, must have one of the best settings of any English winery. It produces several styles of sparkling wine and is exceptionally well set up for visitors, whether you want to eat, stay, taste or simply tour around the vineyards and winery (rathfinnyestate.com).

Towner Eastbourne

One of the leading galleries in the south of England, Towner was set up as a modest art museum for Eastbourne in 1920. It has come a long way since: it will host the Turner Prize in 2023. The permanent collection is strong on modern British art and includes works by Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant and Eric Ravilious. This summer it is holding two exhibitions: A Life in Art, showcasing gallerist Lucy Wertheim’s collection of mid-20th-century modern art, and Reuniting the Twenties Group, which features early works from artists including Barbara Hepworth and Victor Pasmore. Both run until September 25 (townereastbourne.org.uk).

Glyndebourne and the opera

The flourishing of operatic art at Glyndebourne in the 1930s had nothing to do with the Bloomsbury set 10 miles away at Charleston, but there was similarly a lot of love involved. The building of the first theatre stemmed from the infatuation of John Christie – who lived in this impressive country house in an especially scenic fold of the Sussex downs – with a visiting soprano, Audrey Mildmay. They married and together inaugurated the Glyndebourne festival in 1934, with Mildmay singing Susanna in The Marriage of Figaro. After the war, the summer festival went from strength to strength and typically sells out. Not this year though: if you want to go, there are (probably as a result of nervousness about Covid) plenty of tickets still available – including for The Marriage of Figaro (glyndebourne.com).

Ditchling Museum of Art and Craft

Housed in the old Victorian school just behind the churchyard, this is a tiny gem of a museum that hosts exhibitions linked to the remarkable creative history of the village. This summer the main show is Frank Brangwyn: The Skinners’ Hall Murals, which brings together eight of the large-scale panels Brangwyn painted for the Skinners’ Company in London from 1901-1912 as well as etchings and photographic studies. The exhibition runs until October 16 (ditchling museumartcraft.org.uk).

West Dean College of Arts and Conservation

If you fancy yourself as a practitioner as much as an observer, West Dean, the estate owned by Edward James, is now run as a residential centre for teaching art and craft. There are dozens of short-stay courses covering everything from basket-weaving to metalwork (westdean.org.uk).

More on Sussex

Sussex Modern is a group of museums, art galleries, wineries and tourist attractions across both East and West Sussex. A special project this year is a series of illuminated texts placed in seven different locations by the artist Nathan Coley. for more details, see sussexmodern.org.uk. For more inspiration, read Telegraph Travel's guide to the best luxury hotels in Sussex.