17 natural wonders that have been destroyed

Mother Nature’s lost treasures

NPS/Wikimedia Commons/CC0

While many of us dream of visiting the Grand Canyon, exploring the Great Barrier Reef or seeing the Northern Lights, there are some amazing sights that’ll sadly never be able to grace our wish lists. From sea arches that were torn down by crashing waves to glaciers that disappeared due to climate change, discover the stunning natural wonders that are now gone forever.

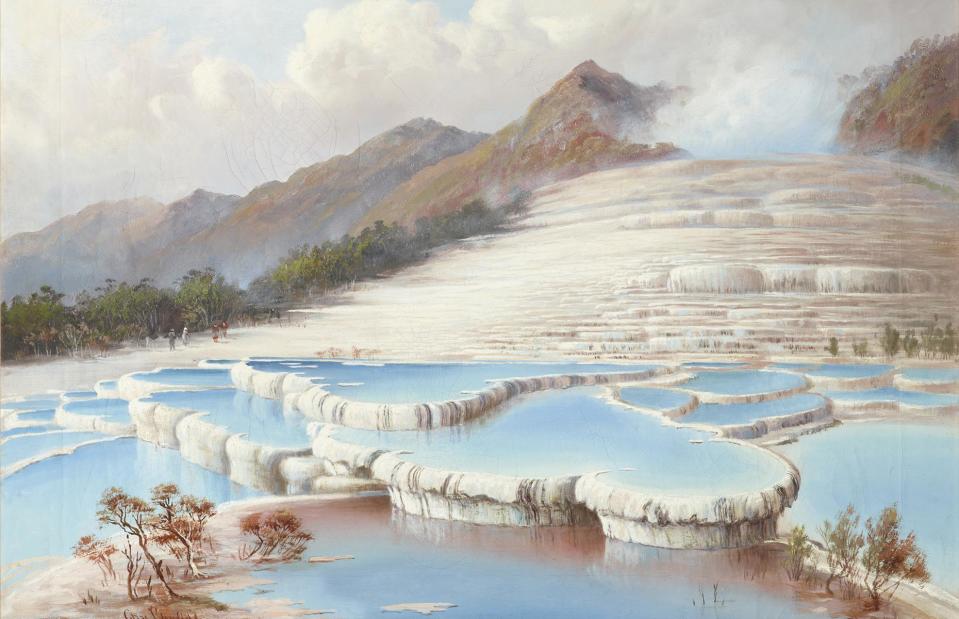

Pink and White Terraces, Lake Rotomahana, New Zealand

Charles Blomfield/Wikimedia Commons CC0

This gorgeous painting, created by artist Charles Blomfield in 1882, looks like the stuff of fantasy. But the rosy-hued pools it depicts were once entirely real. Thought to have been situated on the shores of Lake Rotomahana, in the north of New Zealand’s North Island, the Pink and White Terraces were formed by boiling geysers which sent geothermal water spewing down the lake’s shore. As its water cooled, the distinctive layered pools were formed, gaining their pink color from the presence of sulfides.

Pink and White Terraces, Lake Rotomahana, New Zealand

Brian Taylor Flickr/CC BY-SA 2.0

Yet the natural attraction, which was once considered the eighth wonder of the world, was destroyed by the eruption of Mount Tarawera in 1886. The spewing volcano made Lake Rotomahana expand by more than 20 times in size, burying the terraces 200 feet (60m) underwater. In March 2021, New Zealand research body GNS Science released a detailed map showing the likely location of the former natural wonder, in a resolution that was 400 times better than the previous map they had used.

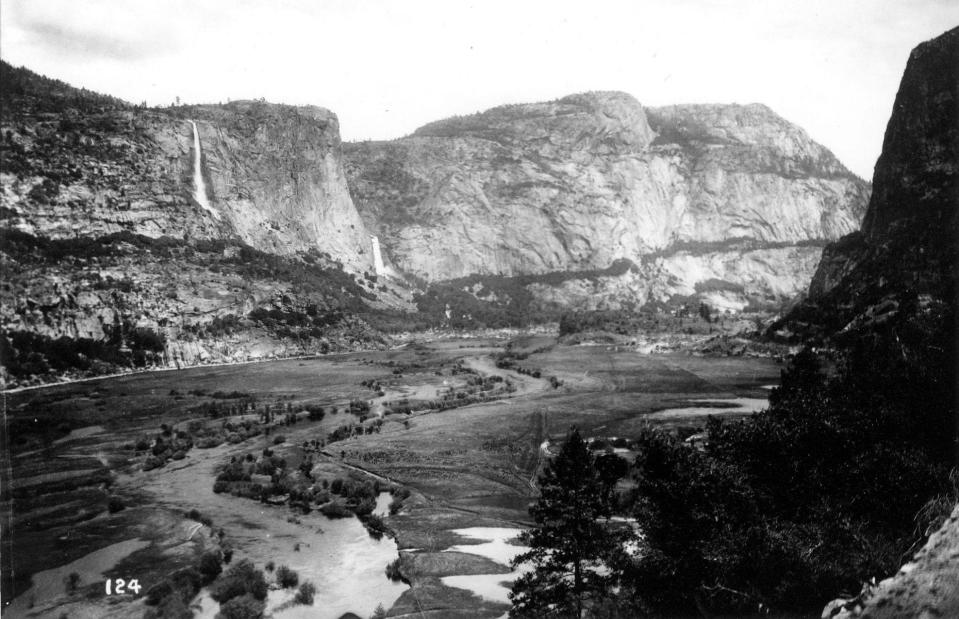

Hetch Hetchy Valley, Yosemite National Park, California, USA

Historic Images/Alamy Stock Photo

Once upon a time the Hetch Hetchy Valley’s beauty was compared with that of the nearby Yosemite Valley. The steep-sided, U-shaped valley was carved out over millennia by rivers and glaciers eroding the granite rock of the Sierra Nevada mountains. It owes its name to the Miwok word “hetchetci”, used to describe the seeds from grasses which were once abundant on the valley floor – along with plentiful trees and plants, as early photographs show. It was also home to a number of indigenous groups including the Miwok people.

Hetch Hetchy Valley, Yosemite National Park, California, USA

Steven Guo/Shutterstock

Nowadays though, the valley floor is buried under 430-foot (131m) deep water. In 1913, Congress approved plans to turn the valley into a reservoir which would supply water and hydroelectric power to San Francisco. Despite backlash from environmentalists, the valley was flooded and the O’Shaughnessy Dam was completed in 1938.

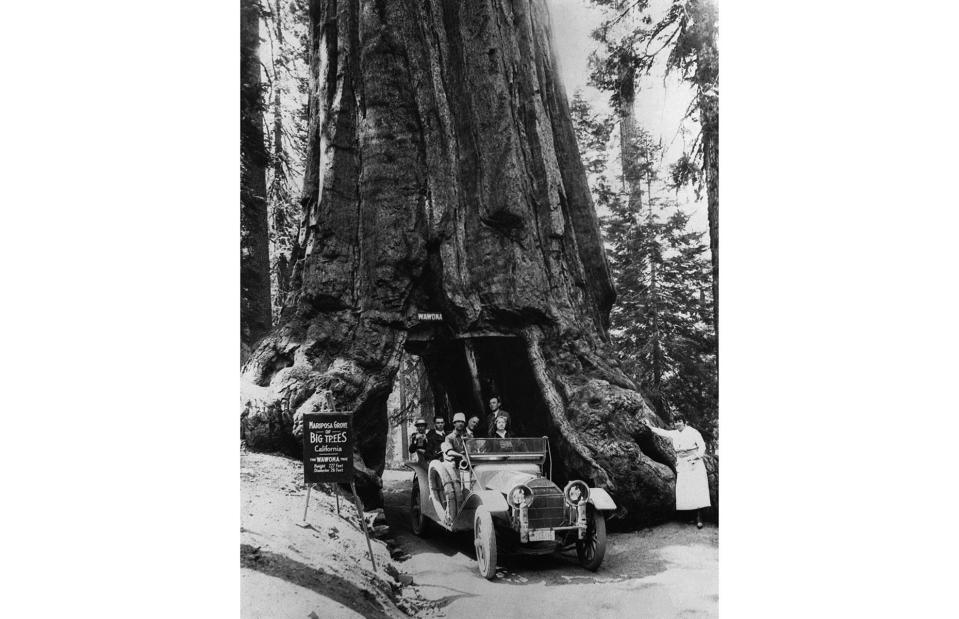

Wawona Tree, Yosemite National Park, California, USA

Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

Photographed here in 1918, the Wawona Tree was a giant, ancient sequoia tree in Yosemite National Park. The tunnel was cut through it in 1881, prompting visitors to take pictures of themselves walking or driving through it – several other trees in US national parks had tunnels cut through them in the 19th century, with the idea being that they’d attract tourists.

Wawona Tree, Yosemite National Park, California, USA

PunkToad from Oakland via Wikimedia Commons/CC BY 2.0

However, hacking into a living tree causes substantial damage to it. So when the harsh winter of 1968-1969 hit, bringing heavy winds, intense snow and rainfall, the Wawona Tree had already been structurally weakened and it toppled to the ground in February 1969. Before the fall, it had reached the grand old age of 2,100 years and measured a towering 234 feet (71.3m) tall.

Tree of Ténéré, Ténéré, Sahara Desert, Niger

Michel Mazeau/CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Moving on from ancient trees to ultra-isolated ones, the Tree of Ténéré in the middle of the Sahara Desert was once nicknamed the loneliest tree on Earth. Shown here in 1961, the acacia sat some 250 miles (402km) away from the nearest tree and dated back to a time when Niger had been much greener and wetter. It had become something of a landmark for those traveling through the region.

Tree of Ténéré, Ténéré, Sahara Desert, Niger

Holger Reineccius/CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Tragedy struck in 1973 when the tree, so famous it appeared on maps, was hit by a truck and fell to the ground. The culprit was never named but many suggested it had been a drunk driver. By way of a memorial, a statue has been constructed in its place, with the original tree currently held in the Niger National Museum.

London Bridge, Victoria, Australia

gjee/Shutterstock

Named after the British bridge which it closely resembled in shape, the London Bridge rock formation once graced the southwestern coast of Victoria along Australia’s Great Ocean Road. But although it took hundreds of years of erosion for the arch to be formed, it fell down overnight…

London Bridge, Victoria, Australia

Philiphist/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY 3.0

Prompting plenty of cries of “London Bridge is falling down”, the iconic structure collapsed on the evening of 15 March 1990. Two tourists had walked over it just minutes beforehand – fortunately, no-one was hurt when it fell down. Today, the piece of rock that once connected it to the mainland has fallen away, but a smaller arch still stands, as you can see here.

Jeffrey Pine, Yosemite National Park, California, USA

David Schroeder/Flickr/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

It was often thought that Jeffrey Pine was the most photographed tree in the world. With its incredible wind-hewn shape, the tree, which was estimated to be around 400 years old in 2003, certainly cast a striking silhouette against the backdrop of Yosemite National Park. It was made famous by a snap from Ansel Adams in 1940 and since then has attracted photographers and nature-lovers from all over the world.

Jeffrey Pine, Yosemite National Park, California, USA

John Krzesinski/Flickr/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Sadly, the gorgeous tree was eventually killed off by the harsh weather that originally gave it its distinctive shape. It died during a drought in 1977 but stood for a further quarter century, before a series of storms in August 2003 led it to crash to the ground. However, Jeffrey Pine has been left in its original spot so that visitors can still see and photograph it today.

Twelve Apostles, Victoria, Australia

Cookaa/Wikimedia/CC BY-SA

Let’s clear something up: there were never actually Twelve Apostles. These distinctive sea stacks along the coast of Victoria, Australia gained the moniker in the 1960s when they were named after the 12 apostles in the Bible, although at the time there were only nine of them. They were carved away from the cliff by a process of erosion which began some 10-20 million years ago, initially creating caves in the rock face which became arches, then sea stacks.

Twelve Apostles, Victoria, Australia

Richard Mikalsen/Wikimedia/CC BY-SA

Yet the crashing waves which tore them away from the cliff in the first place will also, ultimately, be responsible for their collapse. In 2005, one of the stacks crumbled down, then another fell in 2009. Today, there are seven in total, although one is located further out to sea and isn’t as easily visible from the main viewpoint.

El Dedo de Dios, Agaete, Gran Canaria, Spain

Alamy Stock Photo

Located just off the coast of Agaete on the island of Gran Canaria, El Dedo de Dios – or “God’s finger” in English – was once a spindly basalt pillar, named for its finger-like shape. The gravity-defying piece of rock served as an inspiration to artists and a landmark in the local area.

El Dedo de Dios, Agaete, Gran Canaria, Spain

Mjk1980 at German Wikipedia/CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Yet the miraculously tall and thin rock formation couldn’t stay standing forever. In 2005, Tropical Storm Delta hit the Canary Islands and sent the upper part of the pillar crashing into the sea, while only the stubby base remained. Today, the part that remains has been renamed Roque Partido, meaning broken rock.

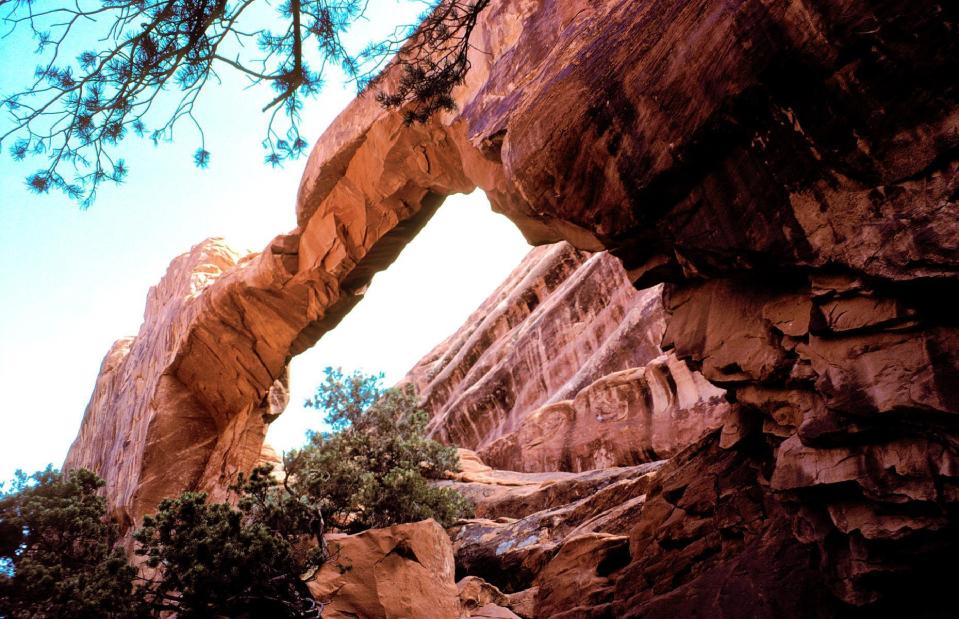

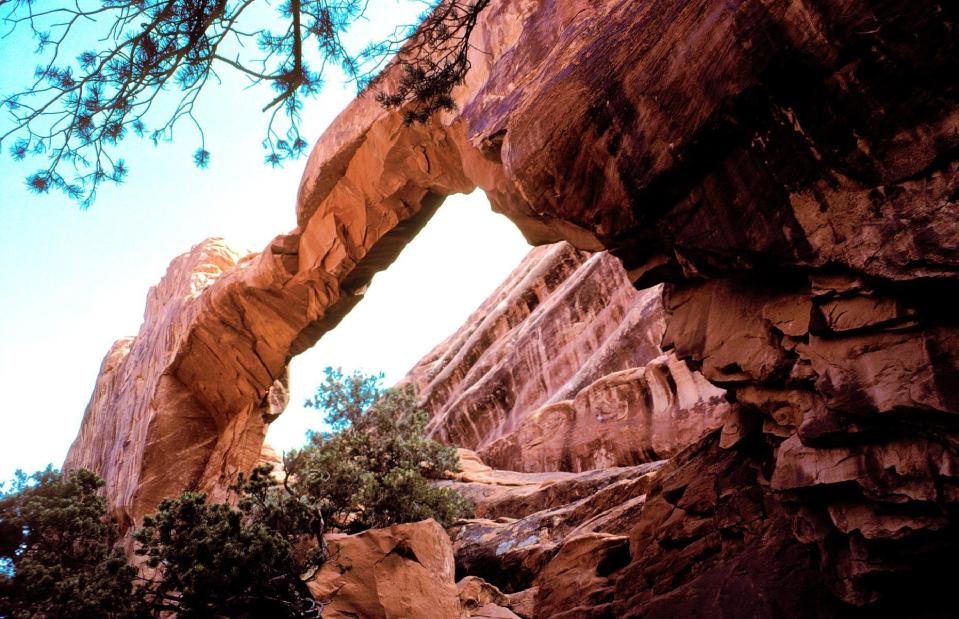

Wall Arch, Arches National Park, Utah, USA

NPS/Wikimedia Commons/CC0

Utah’s Arches National Park contains an impressive 2,000-plus sandstone arches, as well as spires, balancing rocks and other impressive formations. Wall Arch, which was the park’s 12th largest at 71 feet (22m) wide and 33.5 feet (10m) tall, was especially popular with visitors due to its proximity to walking trails.

Wall Arch, Arches National Park, Utah, USA

NPS/Wikimedia Commons/CC0

Sadly, disaster struck on the night of 4 August 2008. Over the course of hundreds of years, erosion had eaten away the calcium which essentially holds the rock together, leaving it weaker and more vulnerable to falling down. It’s not known what the immediate cause for the collapse was that night, but National Park representatives visited the site a few days later and noticed stress fractures in the rock that would’ve led it to fall.

Chacaltaya glacier, Bolivia

Bernard Gagnon/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 3.0

It’s thought that before it disappeared, Chacaltaya Glacier had been around for 18,000 years. The glacier, located near La Paz, was once home to a popular ski resort – which at a dizzying 17,785 foot (5,421m) altitude was the highest in the world. Scientists first began measuring the glacier in the 1990s and predicted it would disappear in 2015.

Chacaltaya glacier, Bolivia

Aizar Raldes/AFP/Getty

Yet, accelerated by climate change, the glacier had vanished almost completely by 2009. It’s estimated that the region’s temperature had risen by 0.9°F (0.5°C) between 1976 and 2006, which made the glacier melt away faster than expected. Today, all that’s left is an eerie abandoned ski resort which is visited by a handful of tourists each year.

Okjökull glacier, Iceland

NASA

Around a century ago, Okjökull glacier in western Iceland covered six square miles (16sq km) and was more than 160 feet (49m) thick. Situated at the top of the Ok volcano, the glacier was thought to have existed for around 700 years and had been monitored closely by the Icelandic Meteorological Office for several decades. According to glaciologist Oddur Sigurdsson, snow had been melting on it faster than it could build up.

Okjökull glacier, Iceland

JEREMIE RICHARD/AFP/Getty Images

In 2014, the glacier was officially declared dead. Which may sound like a strange description for a lump of ice. But glaciers usually work by accumulating snow, which creates enough pressure for them to move, and since Okjökull had reduced to a thickness that meant it could no longer move, it was pronounced dead. A plaque was installed to commemorate it and climate change activists gathered in 2019 to hold a funeral for the glacier, which was the first in Iceland to lose its status as a glacier.

Lake Poopó, Bolivia

NASA/Johnson/Flickr/CC BY-NC 2.0

Situated in the heart of the Andes at some 12,139 feet (3,700m) elevation, Lake Poopó was once Bolivia’s second-largest lake. A mere few decades ago, it would reach a size of 1,158 square miles (3,000sq km) during the rainy season. It was a biodiverse habitat for around 200 animal species, including fish, birds and a large number of flamingos, plus it served as an important source of water and fish for indigenous Urus-Muratos people.

Lake Poopó, Bolivia

Georg Ismar/DPA/PA Images

Yet the once-thriving lake has become a victim of the climate crisis. At the end of 2015, the lake dried out completely following droughts caused by the El Niño phenomenon, leaving a salt desert behind. Although the lake has dried up and rebounded before, it remains dry today and scientists have voiced concerns that it may never return. As well as climate change, the lake’s disappearance was sped up by the diversion of water from its tributaries, used for farming and mining.

Duckbill Rock, Cape Kiwanda, Oregon, USA

Steven Pavlov/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY 4.0

Named for its duckbill-like shape, this recognizable rock had graced the shoreline of Cape Kiwanda, Oregon since the early 1900s. The seven-by-10 foot (2.1 by 3m) formation was carved into its trademark form over the course of thousands of years, and had become a well-loved landmark popular with travelers, locals and photographers alike.

Duckbill Rock, Cape Kiwanda, Oregon, USA

Alberto Loyo/Shutterstock

So in August 2016, when reports emerged that the rock had collapsed, many people mourned the loss. Sadness quickly turned to outrage, however, when they learned of how it fell. That September, video footage emerged showing a group of vandals intentionally pushing the rock until it collapsed. The man who had filmed the video had approached the vandals, one of whom had said they’d toppled it because he’d injured himself on it, calling it a “safety hazard”. An outpouring of messages paying homage to the rock flooded social media, while locals voiced their anger about the vandalism.

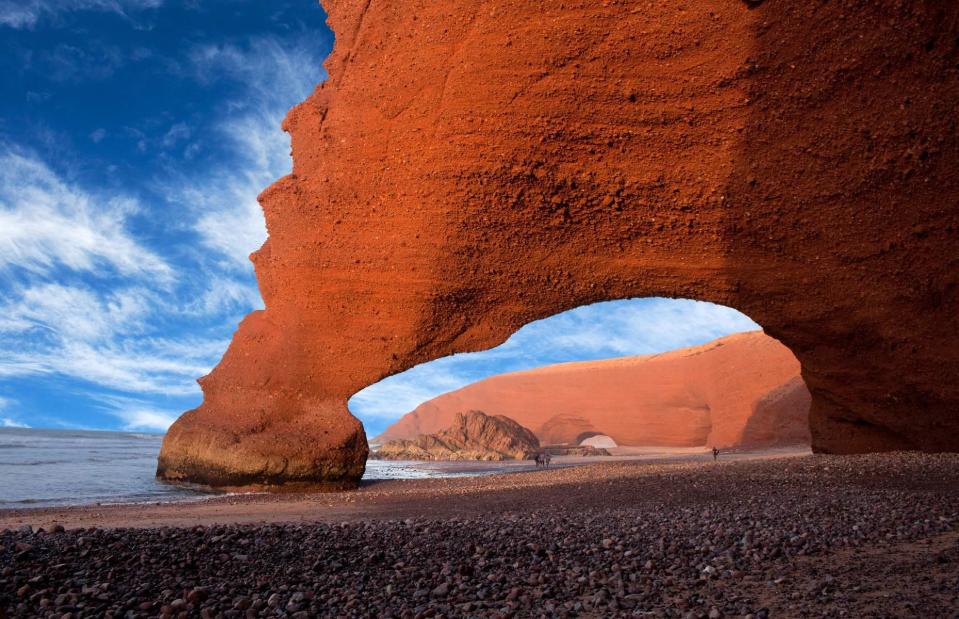

Legzira Beach, Tiznit Province, Morocco

Zzvet/Shutterstock

Few coastlines on Earth quite match the beauty of Morocco’s Atlantic Coast, where the stunning Legzira Beach is located. The weather-beaten rocky beach has long been known for its two recognizable rock arches, which draw in travelers and photographers from all over the world. It’s said that sunset is the best time to visit, when the coastline turns a vibrant red color.

Legzira Beach, Tiznit Province, Morocco

Sadik Yalcin/Shutterstock

In late 2016, one of the two rock formations fell, leaving nothing but a pile of rubble on the shore. The exact cause of the collapse is unknown, although there had been a large crack in it since March that year, and it’s thought that crashing waves probably had a part to play. Time is ticking for the second arch too, as the sea continues to weaken it.

The Azure Window, Gozo, Malta

Sascha Steinbach/Getty

Perhaps one of the most photographed sea arches on the planet is Malta’s Azure Window. Situated on the island of Gozo – the filming location for Game of Thrones and several popular movies – the limestone bridge was one of the most popular attractions in Malta.

The Azure Window, Gozo, Malta

Indegerd9/Shutterstock

Sadly, heavy storms caused the arch to come crashing down in March 2017. Although it was expected to collapse eventually due to erosion, its demise had come sooner than expected, accelerated by the harsh weather conditions. Then-prime minister Joseph Muscat described the landmark’s downfall as “heartbreaking”.

Larsen Ice Shelf, Antarctica

NASA photographs by John Sonntag/Wikimedia Commons

At the end of the 19th century, Antarctica’s Larsen Ice Shelf had an area of 33,000 square miles (86,000sq km). Yet climate change, which has caused significant rises in air temperature above Antarctica, has led it to shrink at a worrying rate. In 1995, the first section of the shelf – known as Larsen A – became detached.

Larsen Ice Shelf, Antarctica

Mario Tama/Getty Images

This was followed by the disintegration of a further section, Larsen B, in early 2002. After these two events just two-fifths of the original ice shelf remained. But the alarm bells were sounded once again in 2017, when a large iceberg broke away from Larsen C in one large chunk, exposing the marine life beneath it to light for the first time in 120,000 years. However, scientists from the British Antarctic Survey say that the Larsen C ice shelf can be protected if actions are taken to curb emissions and climate change.

Darwin’s Arch, Darwin Island, Galápagos, Ecuador

HakBak/Shutterstock

Named after Charles Darwin, the biologist who developed his theory of evolution on the Galápagos islands, Darwin’s Arch was a stunning rock bridge located just off its namesake island. As well as being gorgeous to look at, the landmark is a top scuba diving spot and its surrounding waters are filled with dolphins, sea turtles, rays and fish.

Darwin’s Arch, Darwin Island, Galápagos, Ecuador

Hector Barrera/Ecuadoran Ministry of Environment/Facebook

Disaster struck on 17 May 2021, when Ecuador’s Environment Ministry reported that the rock formation had fallen. That morning, tourists on a boat had witnessed the moment the top of the arch fell into the ocean, leaving behind two pillars of rock. The Environment Ministry cited natural erosion as the cause of its fall.

Now read about the amazing tourist attractions that no longer exist